1/11

conversation with and notation from Cecilia Lopez; reviews

$5 Suggested Donation | If you find yourself spending a good chunk of time reading the newsletter, discovering music you enjoy in the newsletter, dialoguing your interpretation with those in the newsletter, or otherwise appreciate its efforts, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the writing team, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of a project it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians $0.78 to $3.15 for the month of October and $2.00 to $5.32 for November. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations + annotations

Cecilia Lopez is an Argentenian composer and multimedia artist based in New York whose practice plays at the interfaces of improvisation, composition, and installation and often performs with synthesizers, keyboards, or feedback-based systems. Over video chat we talk about installation, spatialization, movement, recordings, songs, and some specifics for select scores.

In 2021 so far, she has released RED (DB) with Julia Cavagna, Gerald Cleaver, and Brandon Lopez, Caprichos with Joe Moffett, and Guilt Tripping with Brandon Lopez and has appeared on Brandon Lopez Trio’s Live at Roulette. View a recent interview and performance video with Moffett as part of the OPTION series here and read a recent interview from Foxy Digitalis here.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission.

Cecilia Lopez: Great, yeah. Can you hear me?

Keith Prosk: Hey! Yeah! Can you hear me?

CL: Hey! Yeah! Sorry, zoom was doing all this weird stuff.

KP: Ah, no worries.

CL: I’m good, how’re you doing?

KP: I’m good, I’m good. It’s nice and cool in Texas, which is a rarity in October.

CL: Why? Is it usually hot? Still?

KP: Yeah, I remember as a kid - you know, Halloween’s coming up - and I remember… sorry I should say I don’t remember a Halloween where I wasn’t sweating in my costume, so…

CL: [laughs] yeah, that’s a good parameter.

KP: Do you have to be back at 1:00?

CL: Yeah, 1:00 and, you know, 1:15 if we go over.

KP: Perfect, well I’ll kind of hop into it if it’s alright but thanks so much for taking some time to talk about your practice for a bit.

CL: Yeah, thank you for the interest, it’s cool.

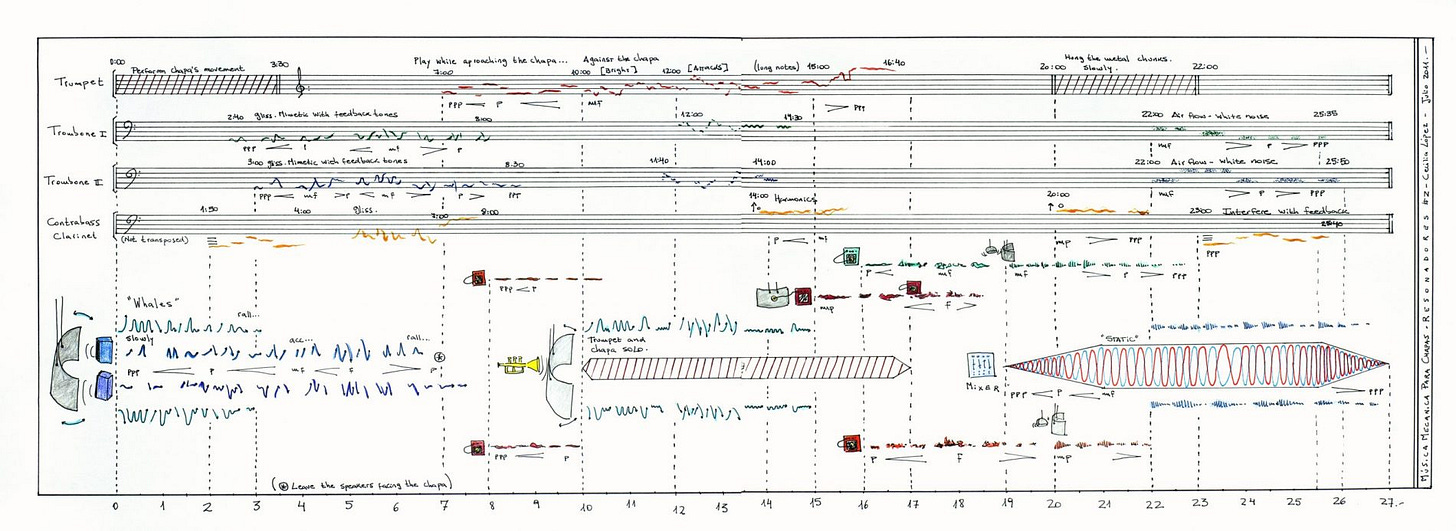

KP: Yeah, yeah of course. So I guess just right off the bat, a lot of your work - Música Mecánica with the chapas, Red with the hanging nets, Machinic Fantasies with the oil drums - it really kind of blends with installation which is usually seen as limiting in its bulk, at least for a single performance or a brief residency, but it doesn’t seem that way in your practice…

CL: can you repeat that last part?

KP: yeah, it seems kind of limiting in its bulk, to have to construct these environments, but it doesn’t seem like it’s limiting for your practice. So I guess what is that limit for you? Or are there things you wish you could do or that you would like to construct that are just too logistically difficult or kind of impossible to do for a single performance or residency?

CL: Oh, I see what you mean. I think I see what you mean by limiting - I’m not 100% clear. Let’s see, all those works, the big-scale works, I guess Música Mecánica para Chapas was pretty flexible, because even if it’s sort of complicated to have the two sheets of metal hanging from somewhere, to set it up wasn’t insane. But Machinic Fantasies and Red, in the version with the double basses and the drums, they’re pretty high production.

KP: Oh, OK, so these venues are commissioning these and it’s kind of a big event to put these on?

CL: Yeah. I mean ideally they are commissioned... I have a version of the drums that I use for Machinic Fantasies in Buenos Aires and I made them at least in 2005. They were functioning in 2005 but I never used them because you need a truck to move them… it’s just the infrastructure was never enough that it made sense to carry the project. So Roulette in that sense has been like a home for these pieces. Because they provide very good tech, tech staff and they have a genie that you can go up to the ceiling and work up there.

KP: Nice. Those are actually the barrels behind you, right?

CL: [leans over, laughs] yes

KP: So yeah just since you mentioned Roulette I know that you’re kind of - like with the barrels and the chapas - you’re playing with space and shape on stage or internal to the practice, but I feel like with installation type of stuff, the ear is kind of drawn - more so than maybe traditional instruments - it’s drawn to how the sound interacts in a space. And I did notice that the recordings of Red and Machinic Fantasies were done at Experimental Intermedia and Roulette and I’m wondering if there’s an ideal space for your practice, sound-wise, or to what degree you’re able to adapt your environments to accommodate different spaces.

CL: Let’s see. Well, to begin with, I think the distinction between installation and music in that sense, sometimes it’s sort of arbitrary. I think that even my music works with sound in space as a material. I work a lot with acoustics and how the sound responds and in a way every place... it’s always site-specific in a way. Even Música Mecánica para Chapas, I remember writing a piece for each performance because it was like, well how many metal sheets can we hang, how many people are there gonna be, how many performers can come to the show, OK I’ll write the piece, you know? I don’t know if there’s an ideal venue. Red has been presented as an installation, for example, in Ecuador, in the fourteenth Cuenca Biennial, but it was there for three months. When Roulette offered me the opportunity to show a new work and I decided to do that, I knew that it had to be presented as a piece - beginning, end - so it’s like, yeah we can do all the installation stuff but it has to be a composition. And for me, it’s interesting to morph the material to different formats, but I think it’s also because I enjoy that in-between space in disciplines. I feel like if an installation is musical enough that you sit down and listen to music, it’s good, and if a musical piece sounds in the space in a way that you feel immersed in the space, it’s also good. Like composing the space in a way.

KP: Yeah. Is there a line between performance and installation other than you not being there for you?

CL: No, I think that’s it, you know. Also, the way it’s framed. If it’s framed as a visual arts show, it’s going to be called an installation; if it’s shown in a concert venue, it’s going to be called a musical piece. It’s like you change the t-shirt depending on where you go. It’s not so stiff for me… I like to experiment with those different formats. I’m working on a piece now, for example, with the rotating oil drums, with John Driscoll, who is a great electronic musician, and because we began to work during COVID we started thinking about it as a performance and then were like, well performances are not gonna be a thing for a while so maybe it should be an installation. So we were thinking about making the rotating systems automatic, just working it out in a way that they don’t need our presence. And it’s interesting to just make those considerations.

KP: Yeah, would you say that one is more satisfying for you than the other?

CL: I feel like it’s a different perceptive experience for people - myself too but I’m making the work. It’s nice to see those different interactions. There’s a lot to learn from that. For example, if the Red instruments are hanging in an installation context, people will come and touch them, shy or not, and the instruments will respond. And that doesn’t happen in a concert situation because, you know, it’s the musicians’ realm. So I feel like the use of the space is different.

KP: Yeah. If you are performing, do you have a preference for how your audience behaves? Like I have a sense at Roulette everyone’s seated right? But it is kind of nice in an installation setting for people to have that context to walk around and actually interact with things whereas whenever there’s an actual person involved, at least in the states, there’s this very… a boundary between the audience really. Do you have a context that you prefer? Like if you could do a performance where everyone was kind of almost interacting with you, would that be desirable to a degree.

CL: Yeah, yeah for sure. I mean, depending on the work. And the space too. If it was a larger space, it works. If you’re in a little room, it’s more complicated, it has to make sense. Machinic Fantasies started like that because… there’s a bar at Roulette, in the lobby, and I felt like the piece didn’t want to have a beginning, like musicians come to the stage and everyone claps. So I was like, how can I break that? So I had the music from the bar playing from inside the drums in the beginning. People came into the space and looked at it and in the program notes it said that they were invited to move and there was a quad sound system set up on stage for people to sit. So the space was kind of broken. And then at some point, more droney sounds started to come from the barrels and the voices, the chattering over the bar music started to go down, which was nice. But I feel like once we started to play people didn’t move that much [laughs]. But it’s nice to play with that, that behavior.

KP: Yeah, and I guess one kind of big thing for installation is that it allows you to play with the distribution of sound in space, to set up like an ambisonic experience where you have different constructions or speakers around or even in the audience. But I noticed in some of the videos I watched of your environments that everything is kind of done up on a stage, and I wonder what the decisions behind that are. If something’s happening when everything’s condensed together that you want. Or if it’s more of a practical issue, like the safety of hanging a bunch of contrabasses above the audience or something like that [laughs]

CL: [laughs] there was a stage… like for example in Machinic Fantasies there is not so much of a stage. There’s a stage because Roulette is set up as a theater so you have to work with that. But as I said there was a four-channel system set up on stage for people to be sitting there and then the two drums were sounding by themselves in the middle of the room and there was no frontal PA, so the actual sound situation was pretty broken in that sense. And Red, if it’s done as an installation, the sound comes from thing itself, right, the thing itself sounds. If I’m playing at a place that has a stage, yes, I’ll use that, but my preference is to avoid it. I have a piece that is called Dos(tres) with two trumpets, trombone and electronics and there as well there’s like a four-channel set-up and the trumpet players move, there’s a little bit of that choreography, so if they move towards one microphone the sound will come from one speaker if they move to another one… so it’s not so… it’s hard to convey that in a zoom video [laughs] but it’s not such a frontal PA either. I actually kind of work against that.

KP: Yeah, and I guess with just the way you are playing with multi-channels and the distribution of sound in space, a big piece of that gets lost in recordings. And I wonder what your perspective on recordings is. Whether you feel like they’re a kind of compromise, because you’re expected to do them, and maybe too much of something is lost, or maybe if you even see a silver lining, like if in losing something you focus the ear on aspects that might be washed out in a performance space.

CL: Yeah, it’s an interesting question. I didn’t do almost any recordings until 2018 of these kind of pieces and then the opportunity came up to put out Machinic Fantasies on XI Records and I was like, you know, I should do it. And I was asking myself the same questions that you have, how to convey the spatial aspect in a stereo setup. I feel it kind of works. I remember Kurt Gottschalk in the program notes says sort of, I don’t know if the visual distracts from the sound or the sound distracts from the visual, like what’s better. In a way it is a compromise but it’s also the only way that you can make the sounds available. It’s good that it exists in that way. Since the pandemic, I put out many other records, more based on improvisation projects and with that material it is easier for me to think on albums. And I feel like going forwards I’m thinking about projects and then how do you make them worth a stereo set-up. It’s an interesting challenge for these kind of works. You only experience them when you are in space, so… yeah…

KP: quadraphonic LPs [laughs]

CL: I mean people do that, but I feel like the amount of people that can - it’s so niche, you know. How many people have a multi-channel set up at home. I don’t. I mean I could do it with speaker cones but it’s going to sound terrible, I wouldn’t wanna [laughs] Yeah, no it is a compromise but two channels it’s an interesting limitation.

KP: Yeah, something to kind of grapple with. Since you mentioned choreography - I noticed after listening to it - the performance of Red on Relative Pitch had dancers. Which I didn’t... I wasn’t able to hear. Sometimes - especially a lot of the Southeast Asian improvisers that have mimes, you can hear the footfalls in the recording - but I couldn’t quite hear the dancers. And it also strikes me that stuff - like with the oil drums and the chapas - that you have these... not necessarily non-musicians but gestural actors that are needed for the music to happen. So how does physical gesture fit into your practice or how important is it to the music?

CL: I mean, it’s funny, the movement in Red, it’s not meant to be done by a dancer but it’s a scored movement. Julia Cavagna is a performer and an object theatre person, so she’s great at doing, for example, the gesture of moving the nets but, yeah, when we were making the record I was like, well we’re gonna put the name but it’s not gonna sound, people are gonna be confused, and it’s like yes [laughs] I’m interested in the correlation between action and sound. Sometimes the musicians do the actions themselves. Like there’s sort of an interchangeable role situation. For example in Música Mecánica para Chapas someone had to move a speaker to feedback and then pick up the trombone and play. I think there’s something about that that came through in conversations before about labor in a way, like the action of making the drum move [makes churning movement] it’s kind of labor, it’s kind of work, and it produces a sound. Many times I try to put a motor on them, but I like the gesture of having to make the drum move or stringing the nets. I feel like I’m working with technology and electronic sounds and that makes it more humane, more organic, more related to the human experience of making things happen and not so much you know [air presses button and throws hands up] like a hands free and everything works [laughs]

KP: [laughs] yeah I was gonna ask if it’s an intentional contrast or a reaction to a common criticism of like synthesizer playing usually being subtle movements…

CL: I guess so, in those kind of works sure. But the piece with the cables, it’s almost a joke in that sense, right. With all the wires and the reaction to them. When I play synth though I don’t move much [laughs] and I also turn some knobs, so I’m guilty of that myself. But whenever I’m working, creating technical interfaces that deal with electronics, I usually find myself doing that, rejecting that comfort in a way. People complain, I remember people complaining in Machinic Fantasies like, yeah you have to turn this barrel for thirty minutes and they’re like [rolls eyes] geez!

KP: [laughs] yeah, I saw that you at least provide some breaks in Mechanic Fantasies so they can rest their arms. I had another conversation recently and it also had a practice that was really light on gesture in performance and that was maybe because the person wanted to be a part of the shared listening experience with the audience. I guess how - obviously you’re listening to make sure the music is moving in a direction that you kind of want it to go - but do you have any observations about your role as a listener while you’re performing?

CL: Yeah, well, because a lot of the pieces are improvised I’m responding to listening in real-time. I usually work with graphic notation when I compose. Some things are more notated but there’s usually a looseness in terms of the actual sounds and there’s always a response to listening in that sense. There’s a direction, there’s a zone, maybe if it has to be forte or minimal, but you’re responding to whatever is sounding. I feel like feedback is that both conceptually and practically, because you’re listening and producing, and you can’t predict… it’s indomitable. You have to listen to what’s happening to be able to measure how much you can do or not or which tone you get, you don’t know that.

KP: Are your systems usually pretty fragile? Like if you turn a knob too much is it like a really loud, high-pitched sound?

CL: [laughs] yes, yes

KP: I’ve been kind of messing around with an amplifier a bit and that’s the struggle, right, [laughs] just trying to actually control to some degree feedback and not make it just a high-pitched noise.

CL: I think one of the descriptions of Red that I wrote and it’s still relevant - some things over time disappear from promo material - is that I work with unstable feedback systems. And that’s kind of accurate, because if you have one-tone feedback system, it’s more prone to go insane but if you have many channels doing that they kind of stabilize themselves, like before one takes over another one comes in so it becomes this thing that’s wiggly and changes but it doesn’t necessarily crash. And then I guess the pieces are also fragile in terms of materials [laughs] I need to carry a soldering iron every time that I go to play and I usually use it more than once [laughs]

KP: [laughs] nice. So most of what I was familiar with before listening to Red was your improvised stuff - or at least what’s not written down - but then you do have these graphic scores behind your installation-like work. What’s behind the decision to write something down? Or what does composition allow you to do that otherwise wouldn’t be possible?

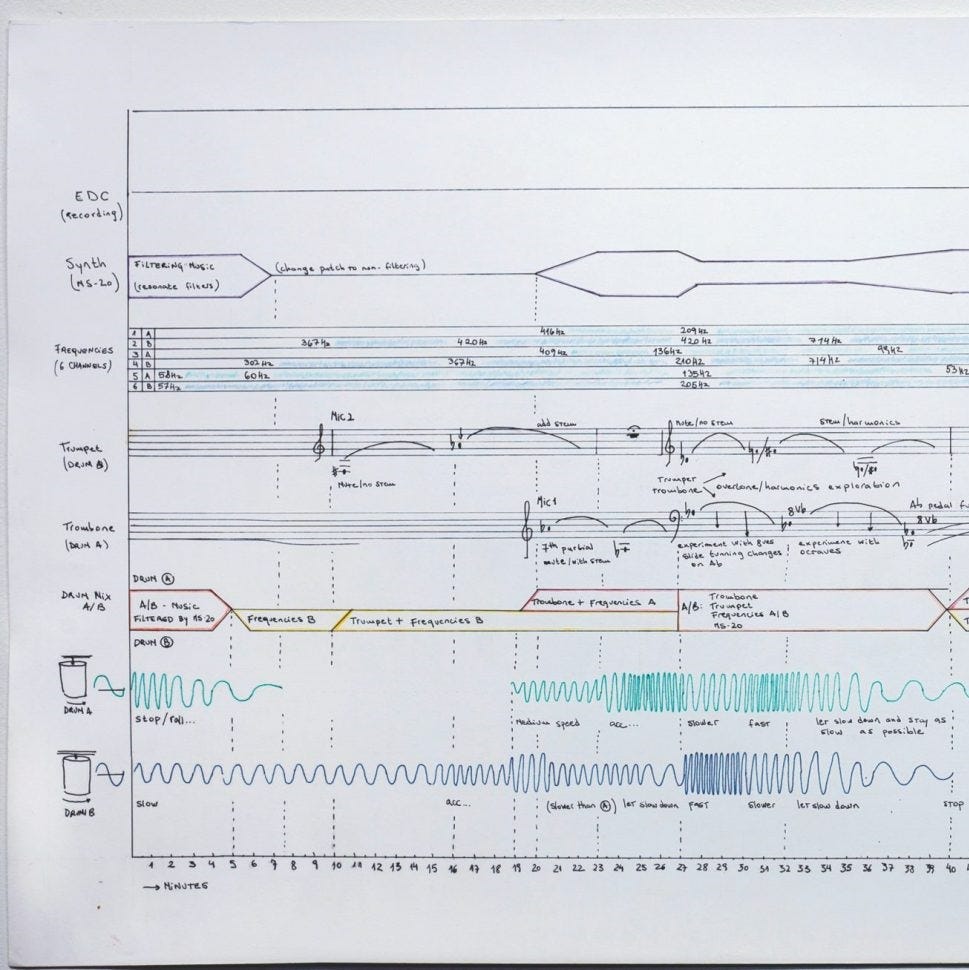

CL: Well, whenever I’m playing alone with those systems, I improvise. Because it’s easy for me to manage. For me there’s different layers of composition. The first one is the hardware and the signal flow, and that’s usually pretty complex. In all of those pieces. There’s something that sounds and comes out from somewhere else, then at some point from a different place, there’s changes in the set-up through the piece that I have to do in the mixer for things to happen, and just how things are routed - it’s one layer of the composition. Usually pieces have a routing diagram, and then there’s the composition. For me it’s a way to visualize those layers interacting in time. So if I’m playing with someone, it’s a way to know that someone is going to do something at some point and when that happens I have to do something to enable the sound to do this or that. I wouldn’t know how to do it otherwise [laughs] it’s just too complex. Yeah, it’s not so prescriptive, or I don’t find it too prescriptive. I find that it still gives - while it has a direction - it gives enough freedom for things to happen in ways that are unexpected. But yeah for those pieces I need some kind of order, if not it’s like [shakes head] yeah.

KP: When you’re putting these compositions together with other instruments, are these compositions kind of done first and then you take it to the group, or do you come up with them with the group and then put it to paper so everyone has a map?

CL: Usually… both. When I was working in Buenos Aires with Música Mecánica para Chapas, the people that I was working with, we had a practice of working together. So we usually played many times, we would rehearse at my house, so I would just write the piece and maybe rehearse it once and just play it. But in these works that are more specific, like the piece with the two trumpets and the trombone or Red, which just came out, I usually do get together with the players and work through the material and then I write using that feedback. I’m not a composer that has all the orchestration in my head and I know exactly what the instruments are gonna do and how to write it, so it makes more sense to get together and be like, how would you respond to this, how would you call it, which techniques that you do would work, and then I record those rehearsals and write the piece. So they could be played by whoever and they would always be different. I think they would be different even if we played again [laughs] but yeah, they’re written with the feedback of the musicians for sure.

KP: Nice. The first thing I noticed with all of them is that they don’t have instructions. So I guess this has been answered - or I think it’s been answered - along the way, but do you expect to be present during the performances of these pieces?

CL: So far I have always been.

KP: Would you be comfortable with other people performing them without you, and do you think the scores allow for that?

CL: I think the scores allow for that. But certainly they would need to talk to me and they would need instructions.

KP: Yeah yeah, especially for like the mixing set-ups.

CL: The set-up but also the tuning. For example, when I presented Red in Ecuador and the installation was running for three months, I had to train the people in the museum to tune it. Because after a few days maybe it will go too much in one direction or another, or someone would turn it off and then they wouldn’t know how to turn it on [laughs]. So we were there for about an hour playing with the mixer and I was like, yeah you need to feel comfortable with that. I feel like the pieces could probably be on their own but they’re not written for... I wouldn’t give it to an ensemble like, OK yeah, just go do it. Or maybe I would. I just feel like it would be hard.

KP: Yeah, definitely. You mention that you build in a nice degree of interpretation or a degree of freedom but are there some specific places where you don’t budge, where you have something very specific in mind that you want to happen?

CL: Yeah. Definitely. There’s places that are very specific and then there’s places where I feel that the piece is richer if the person that is playing brings their own vocabulary. I remember for example playing with people that play a lot and shred and I was like, this is not about shredding. It’s just a different vocabulary. It’s the vocabulary of those instruments. I feel that in those cases when you’re playing with objects, what they do is very limited. It’s kind of stupid in a way. The net swings back and forth so the sound is like whe whe whe [swaying in chair] If you play a crazy thing, you’re not talking with it. So in a way you have to tune with that logic in order to make something that will make sense. I feel that Gerald and Brandon did great work in that way, sort of tuning in a different logic to play with them.

KP: And then as far as sound result, one thing that I saw in bicéfalo 2 from Música Mecánica, you have the squiggly arrows for some of the instruments, but then you also have what I would call a crunchy texture where it’s like two waves but joined in shape and filled. I guess whenever you do certain shapes like that, do you have a pretty specific sound result in mind, or is that left up for interpretation?

CL: That’s like a motion analogy. The first piece that I wrote using graphic notations was for wine glasses. That was in 2002. I was reading a book about physics and sine waves and I didn’t know how to write the piece and I thought of the analogy between the sound... like, if you have a period of the wave and you put it together it’s a circle, right. So I was like, OK so I can actually write in time the movement of the finger around the circular edge of the wine glass, so that’s the score. And then I feel like that analogy became handy many times, with the barrels it describes the speed of the rotation of the drums so if it’s fast you see the high frequency wave and if it’s slow then you see that it’s slow, and with the sheet metal, because you’re using both sides to curve it, if you look at it vertically, you would get these like contour-facing sound waves, so it’s very motion oriented.

KP: Yeah since you mentioned the choreography as well, that actually stuck out in these scores too. Where I feel like there’s a lot of dynamic direction or volume-related stuff but more than anything it’s more motion than pitch or other sound aspects.

CL: Yeah. Speed, speed sometimes is more an issue than… you know if something is fast and there’s a lot of action or if its steady.

KP: Yeah, and a lot of these pieces are in absolute time and they’re pretty... I noticed that the recordings of Machinic Fantasies and the two of Red, they’re maybe a few minutes short but stick very close to the time.

CL: Oh, you were looking with the score with the recording?

KP: Yeah. Are y’all usually pretty strict with what things happen at what time or is it more a relative - I mean y’all are all improvisers usually so if someone moves then y’all are ready to move with them - but…

CL: Yeah, a little bit, yes. But some gestures are pretty specific. Its not like sixteenth notes [laughs] right. It’s like one second, two seconds, sometimes I’ll miss a cue myself. But mostly because there’s so much routing interaction. For example, if I miss a cue maybe someone will be doing something and it won’t even be sounding, so it has to be somewhat precise.

KP: mmhmm, the sequence at least does.

CL: Yeah, and then because the pieces are so long, the development is long so there’s more room, like one to two seconds it’s not a big deal in an hour, right. Yeah, I feel like there’s sort of an envelope for actions, like a range.

KP: Yeah, yeah, and then you kind of… or, I got a hint of this when you mentioned that you construct these pieces with a lot of feedback from the musicians but I know that you’re a close collaborator with Brandon and his recent collaboration with TAK vaguely describes a non-hierarchical composition mechanism and I noticed in one of your videos for Música Mecánica that, while you were usually operating the mixer in the center, there are moments where you’ll trade places with one of the chapas operators. I don’t know, I guess do you try to cultivate a non-hierarchical composition or environment and how do you cultivate that?

CL: Yeah, well, it’s tricky to do it, or it’s been trickier for me to do it since I’ve been in the US because I feel like the environment is so professional in a way and things are very distinct, roles are very distinct. I feel like one of the important things for me – in Música Mecánica para Chapas - there’s no right way to play a piece of sheet metal, right? There’s a way that I imagine how to do it, but anyone could do it with the score. And then you figure out your own way of making it sound good. So in that sense the pieces are very accessible. It’s actually something that I’ve been thinking about, like how to… the same thing with turning the oil drums. Anyone could do it, you have to be listening though, but it’s cool that anyone could play… not everyone can listen but potentially non-musicians can play that in a musical way so it’s not so restrictive.

KP: Yeah it’s kind of like it’s simple but unfamiliar as an instrument so it requires someone to figure it out in practice...

CL: yeah but it’s also not about virtuosity. It moves you out of that logic and also out of the logic of… it’s the same with the scores, you don’t need to read music to read that score. You just need to be able to manage a timeline and actions and for me that’s important. I was thinking of the Scratch Orchestra and all those works that are very open in terms of that and music is not necessarily attached to knowing your instrument or being good at it. Music is something else. I feel like those things bring it down from that hierarchical, you know, like composer, musician, who is doing things well, I don’t know, the feedback does this [wiggles hand] it does a very limited sound, it doesn’t matter how many notes you can play. Maybe someone who plays two notes can relate to that better, you know. I’m interested in breaking that logic in a way.

KP: Yeah, yeah. Another thing I noticed to is that with these scores everything is on the same page and everyone gets that page, so I guess instead of players staying in their lane and knowing where they are only relative to everyone else, everyone has the big picture and everyone can interact with the same information type of thing. Very cool.

CL: Yeah. I think it’s important. Sometimes people ask me actually [laughs] to have things break down like, this is too much information. OK. If it helps. For me the score is basically like a visual map. Sometimes you’re like, what is that sound and then you see it and you’re like, oh it’s that thing coming through the amp, and then you understand what’s happening more in order to be able to relate to it.

KP: Yeah, and maybe if it’s overwhelming at first at least it encourages figuring out how you contribute to the big picture…

CL: yeah. And that’s why, you know, the drawings are very friendly, it’s pencil and ink with colors [laughs]. It’s very silly.

KP: Música Mecánica was around 2011, right?

CL: Probably from 2005 to 2012

KP: Oh, OK

CL: yeah, yeah all the time that I was in Buenos Aires doing active performances, they probably span those years.

KP: And then Machinic Fantasies and Red are both around 2015?

CL: Machinic Fantasies is 2018. And Red, from 2015 on, you know, I’m still performing it.

KP: Nice, yeah, it’s always in motion.

CL: It’s always new, in a way. I had a performance on Friday and as I was setting up I realized that the last time I played the instrument was March 2020 cause I set it up to make a video in my house and I was like, oh it’s been one year. I don’t practice those pieces so if you play it once a year it’s always kind of new and you change.

KP: Yeah, you forget a little bit of it and make up some new stuff. I guess with all that time, there’s a lot of similarities between them. The movement based squiggles, I don’t know, what I’m calling the dynamic diamonds or whatever [laughs]

CL: [laughs] oh, like the crescendos and decrescendos?

KP: yeah, and I guess the set-ups of where everything is in relation to space but in what ways has your symbology changed over time and why? I noticed that - and this could be just ‘cause the piece call for it - but some of them might contain staves but not until Machinic Fantasies did I see pitched material, or Red has the actual orientation of the bass and bass net in relation to the speaker and likewise with the drums in relation to their speaker, but there’s not anything indicating where the barrels would be in Machinic Fantasies. So I guess beyond specificities of the piece, are there certain things or problems you’ve had to address as you’ve continued writing things down?

CL: Yeah, sure. In a way the score also works as a reminder for me of what the piece is. Recently I went back to one of those scores to revise a piece and I was happy to see that all the information was there, it can be done again. Which was kind of amazing because I thought it was lost in time. So you know when I write, for example in Red, what comes through what, it’s for me to have a reminder of how that is working in space so if I do it again I’m like, oh this is what’s happening. I feel like the pieces that work with feedback, it doesn’t make sense for me to write specific pitches because I don’t know what the sound that I’m going to be getting is. So when I started writing specific pitches is in Machinic Fantasies and Dos(tres) which is a piece for two trumpets and trombone, it’s because I’m also using specific sine waves. I’m having musicians relate to specific frequencies, so it’s gets a little like, yeah you have to play this note and go up from this note to this and do a glissando there. I guess that’s - it’s not tonal – but it’s pitch specific.

KP: Yeah, I noticed more than anything else that I’ve heard that Mechanic Fantasies really hits you over the head with the beating patterns, which I love, but I imagine that takes a little specificity of pitch...

CL: yeah, looking at the score now, you have the actual hertz, you know. There’s a whole multichannel file with frequencies. And again that’s mostly for me. So I have a file that is on my sound editor that has all those frequencies running, and the notes that the players are doing are related to that, so if I see that in the score I’m like, oh this is what’s happening. This is related to this and this is related to this. I don’t know if anyone else can make sense of it, but it works for me.

KP: Just to knock out a few specific questions about the symbology, so with what I was calling the dynamic diamonds I know that you have the traditional dynamic indicators in Música Mecánica but then you also have…

CL: oh, I see what you’re saying...

KP: yeah, you have these kind of filled shapes. Some of them are blank, and then some of them have waves in different amplitudes overlapping, and I’m wondering if those are difference tones, and if those shapes are not filled, what do they indicate if dynamics are already indicated elsewhere, like on resonadores 2.

CL: I think it also has to do with the fact that I am performing the pieces. So if I am on the mixer, those parts mean that I am doing feedback with the sheet metal, but it’s static so I’m just eq’ing in the mixer and what you get is some kind of beating but there’s no action besides someone being in the mixer eq’ing.

KP: And then in Machinic Fantasies, well, I guess you don’t actually include the dynamics there, are those shapes indicating dynamics?

CL: Yeah, that would be the general rule…. I feel like the general logic would be, and again, it’s related to sound waves, amplitude runs vertically high or low and, because time runs horizontally, speed it’s usually related to how things move in a horizontal axis.

KP: And then I noticed on some of the Música Mecánica pieces that some of the amplifiers are colored differently. What do the different colors indicate?

CL: Because I’m using these little Marshall amps, the little two-volt Marshall amps, it’s just different amps… normally one person would play one color over the whole piece, so it’s like the same amp that is doing one thing and then it’s doing another thing. So there’s one line for one amp and then the other color is someone else, it’s like a different line for a different amp. It’s just variety in orchestration [laughs]

KP: yeah yeah just to indicate it’s another player...

CL: yeah but it’s the same with the speakers. If you look at the speakers, the big speakers, they’re both blue but they are slightly different blues.

KP: Yeah, yeah. And I guess one thing that I found super interesting is that - I mean, I guess music is kind of movement, like it implies a distance through time - and now that you’ve mentioned that you indicate the chapas flapping through those lines I might be off - but it struck me as interesting that for the speakers the lines indicate a physical movement like away, up, down, around the chapas, but for the instruments like the trumpet and the sax, they seem to indicate tonal movement, which is interesting…

CL: Yeah… also it’s really hard to make a score like this proportional to time. It happens in the piece for copas, for the wine glasses, but then in the other pieces, if you have forty-five minutes in one page, you can’t actually write the whole thing and make it readable. So there’s usually a behavior being described. But I would tell the musicians you don’t have to play looking at the score. I’m asking you to do glissando-ish stuff, but then if you have to do that for thirty minutes you’re not going to be looking at my lines for thirty minutes, it’s not going to make any sense [laughs] That’s not the intention.

KP: It’s just to give a sense of movement, instead of like exact movement.

CL: Yeah and there’s also the … language… I mean the words, sometimes they’re hilarious but there’s a lot of information there for the players too. Like for example in Red there’s a part that says “Hitchcock” for the double bass because when we got together to work with Brandon there was like this “Hitchcock” thing that happened, sort of, you know. Well, it sounds like “Hitchcock.” When I heard the rehearsal, I thought well if I say this, then he’s gonna know what I’m saying. It’s kind of funny, so I’m just going to write that. If someone else ever plays the piece I’ll just explain, yeah yeah this is what you’re supposed to do [laughs]

KP: [laughs] I saw “whales” too somewhere...

CL: yeah, Satie existed. I play those scores. I love the poetic instructions that don’t make any sense like “put your hand in your pocket” while you’re playing the piano.

KP: Yeah but it also makes a lot of sense, like it actually sounds like how you’ve described them.

CL: Yeah I feel like it’s helpful sometimes more than trying to be very specific with the notation, like have an image that you’re going for. There’s a lot of whales in those scores...

KP: Whenever you’re working with performers what kind of questions do you get asked the most? Or what is intentionally on your part undetermined and where is the interpretive tension or do you maybe try to put in some interpretive tension? And whenever you get asked those questions, do you let them figure it out or are you a little more direct with what you want?

CL: Well it’s tricky. Usually I work with musicians that are super open to this kind of thing. Whenever I have worked with ensembles in the past, it’s been harder, because people want to be told what to do and these pieces don’t work like that. That’s it. That’s not my preferred method. At least with these kind of works. I feel that there’s a lot of this that is experiential, like actually you need the person to be going through the frustration of trying to relate to that sound and it sometimes doesn’t work. And then it’s like, OK but what does work. And you can only get there through things not working. Usually the rehearsals for the chapas pieces were a disaster always [laughs] ‘cause it didn’t work, you know. And by means of understanding, for example, where you have to put your body with the speaker the third time you are like, OK I get it. It’s very personal because it’s sort of embodied. So it’s like, oh yeah if I put my arm like this and the speaker here then it sounds better. I’m like, OK cool. If I tell you to do that, then it doesn’t make sense. Yeah usually I’m pretty stand-offish. And it’s tricky, you have to manage personalities in that sense.

KP: And I imagine particularly with the chapas the sound actually changes with the shape that’s in front of it, right, so everyone has to figure out their own thing.

CL: Yeah, and sometimes the instructions don’t make sense. I remember one show that we played in which for some reason you would get the feedback when you pointed the speaker to the audience and not to the sheet metal and then you have to break the score and that’s what you have to do. So it’s very… you were asking about listening and a lot of the work is embodied listening, in that sense, and you can’t prescribe that. Sometimes your whole expectation will be completely betrayed by the situation.

KP: Yeah, yeah. I guess that’s most of what I’ve got. Did you have anything else that you wanted to discuss or illuminate about your practice?

CL: uh… Consult. Can I get a consultation? Maybe some help? [laughs] No I don’t know. I’m going over the scores to see if there’s anything else that’s worth discussing but I think we touched a lot of parts. Um…

KP: I guess one kind of side thing, I actually listened to a bit of Vigilante Margarita this morning and I wonder if you’re... you know a lot of these composed pieces are a little longer, in the twenty-minute range to an hour-plus, and I know your improvisation is a little punchier with shorter durations - I just saw the Joe Moffett duo that’s coming out and how short some of those tracks are - but I wonder if you’re interested or if you still kind of do songs with Vigilante Margarita... not necessarily with them but are you still interested in that kind of musicmaking?

CL: Yeah, I am. You know, it’s weird. In a way, that was a very specific collaboration group. With Guillermina Etkin, who played piano and singing, we studied with the same composition teacher at some point, and we knew each other for years, so there was something about the humor and probably the cultural context that came into play there that was super natural and playful. I like that from songs, that you have the language element and you can bring very different content in. And since I moved to the states I haven’t found people to do that. ‘Cause I don’t wanna write a song and be all serious about it … it was more like I would write a thing, I would send it to her, she would put music, or she would send me a song with the music and lyrics and I would be like, oh the lyrics suck let me change the lyrics, or the other way around. I just haven’t found that kind of close collaboration that allows that playfulness, to be honest. Maybe it happened in a specific time. I do have like short lyrics and little pieces of songs but I’m not so interested in doing that on my own.

KP: Yeah it’s sort of like a band or group thing.

CL: Yeah and bands are harder in New York, because everyone’s doing their own thing and everything is very professionalized, South Americans are more inviting in that way, ‘cause you have economic crisis or something and you don't have a job and all this time [laughs] People have more time to meet each other…

KP: In your experience travelling the states, is that like a New York thing or a US thing in general?

CL: I haven’t travelled the states so much, but one thing that I did notice when I started coming here was that everyone played solo a lot. And for me music was usually a collective thing. Like Chapas was kind of collective, you know. But then because there’s so much touring and stuff like that, yeah, sure, if you play solo it’s easier. It’s more functional. We’re not so function-oriented down there. Because things don’t work so well anyways - and so that creates different working methodologies. Like I’m here now for example and I don’t like to play synth on my own because who wants to hear another solo synth set. I’m not sure that I want to be that person. But I find myself being like, if I did that it would be very easy for me. Because everything fits in a suitcase, it’s easy, I show up, I play, and leave. I have been resisting doing that for awhile. I don’t know, it might happen at some point. It’s interesting how the economics and social context of music changes the music itself.

reviews

Ellen Arkbro - Sounds while waiting (self-released, 2021)

Ellen Arkbro performs four of their own compositions for organs and cymbals on the 48’ Sounds while waiting.

“Sculpture I” and “Sculpture II” are each sidelong, for two organs, and seemingly two chords sustained for the duration. One is perhaps more radiating throb and chirping and one is perhaps more dancing harmonics and stuttering. Both create a strata of beating patterns for the consciousness to wander. The body too, because in their continuity they both recognizably spatialize sound, its components variously accentuated depending on at least distance from the sound source and proximity to walls if played back in open air or on the shape of the ears and sinuses - changed by way of yawns, hiccups, and other soft tissue movements around the skull - if played back in headphones. And in their continuity it might be difficult to determine whether minute variations in sound come from the sound itself or are only inconsistencies in perception or both. They are both interactive teeming living ecosystems of harmonic relationships rich with movement from something that could be considered non-movement - an interesting in-between space. “Leaving dreaming” gradually shifts among chords, likewise creating new combinations of beating pattern behaviors, hastening or slowing a little with each change, suspending a single robust singing beating among their individual stacks of pulses. And “Untitled rain” for two organs and cymbals is significantly harsher in texture and briefer in duration and I imagine that the resonant cymbals interact with the organ harmonics but I cannot hear it for the skittering hits.

Keith Prosk

Lucio Capece - Epimoric Tide (Entr'acte/Stellage, 2021)

Lucio Capece arranges a rhythmic 37’ solo for analog synthesizer, drum machine, eq in feedback, pedals, sequencer, and slide saxophone on Epimoric Tide.

The backbone of the track is a baffling polyrhythm of two beats in epimoric ratios that as far as I can tell remain static yet evoke a sense of cyclical propulsion, of phasing, and of something closer to a stumbling arrhythmia. Sustained slide saxophone tones are not readily identifiable outside of their associations with whispering hiss or fetching saliva but might blend with synthesizers in gliding highs and rumbling lows with their own overlapping relationships. As the synthesizers converge towards a peak density of layers, they also gradually intensify in volume and beatings to assume a more rhythmic character by the time the drum machine beats drop out. Synthesizer layers gradually accrue again to abruptly cease and reveal a refraction of the original beat in the final moments as if it could begin again. As the notes suggest, a few simple variables in intersecting relationships result in a complex experience in which an environment that doesn’t move too much is perceived to move a lot. Its textures and the degree of its minimalism remind me of To Rococo Rot’s sound in the ‘90s but in labyrinthine rhythmic contortions.

Keith Prosk

Angharad Davies - gwneud a gwneud eto / do and do again (All That Dust, 2021)

Angharad Davies plays (and plays again) repetitive violin on the single-track, 52’ gwneud a gwneud eto / do and do again.

There are layers of hasty woody bow drill rubbing, wobbling harmonics, and the intermittent whistling and wheezing of strings sounding from a bowing gesture whose iterations contain noticeable variations but are similar enough to seem repetitive for the duration of the track. Its moving parts in incongruous cadences conveys a sense similar to being inside a vehicle breaking apart at high speed. And like shaking it simultaneously seems not moving and moving, repetitive and not repetitive. Its subtle shifts sometimes curiously isolated, the speed of strings increasing while wobbling sines remain the same or vice versa. While I imagine fatigue contributes to its minute dynamic instabilities, I’m somewhat surprised to not hear more obvious signs of it.

Keith Prosk

Elena Kakaliagou - Hydratmos (Dasa Tapes, 2021)

Elena Kakaliagou performs five of their own compositions for solo horn on the 29’ Hydratmos.

As the notes about transitional states suggests, each track is an unfolding of ambiguities mediated through the horn. “Dampf” is embouchurial breath and mouth sounds - tongue clicks, stops, and slaps, the rolling purr of alveolar trills, and more quotidian sounds from combinations of saliva and lip and cheek - and fragments of speech through the horn, whispered, megaphoned, further blurring the fuzzy line between the mouth morphologies and sound results of horn-playing and linguistics. “One who never saw the sea, but had shells instead of ears” is foghorn blows amidst tempestuous breathplay, extended tones quavering in longer durations like a distant sound does in wind, some musing on the similarities of the wind of the air and the wind of the lungs. “Ascending” is melodic clusters that alternately appear rising and circular and might question whether the perception of musical movement is so tethered to pitch relations or if it’s better conveyed through variations in cadence, duration, and volume. “Slow Trans” seems to examine when a tone is not a tone, mostly sustaining just one tone, a little modulated through a kind of phasing or pitch shifting effect, brassy distortions in overblow, and what might be a humming vocal multiphonic. And “Damp Room” features the linguistic sounds of “Dampf” though with an ululating horn presumably in playback, its two voices spatializing the room in their sound though its unclear what combination of distance or volume or maybe something else creates this effect.

Keith Prosk

Masamichi Kinoshita - Study in Fifths I (Ftarri, 2021)

Masamichi Kinoshita, Airi Kasahara, and Seira Murakami perform a Kinoshita composition for electronic sounds, harmonium, and two flutes on the hour-long Study in Fifths I.

It is from the fifth concert of a series in which Kinoshita showcases the harmonium at Ftarri and like the second, Ftarri’s Harmonium, its composition features clever number games with a particular interest in prime numbers, fifths, and spiral or whirlpool patterns. Tracing the particular mechanisms described in the notes in the sound result seems difficult to impossible but the music does convey a complex clockwork of moving parts regularly converging towards moments of cohesion. Electronic sounds additively layer and then constantly substitute for a revolving constellation of harmonic relationships that emit conspicuous beating patterns, in textures of penetrating singing and deep bass resonance, hastening and slowing as they surface like the decreasing frequency of waves from drops in a pool. The nasal yawn of harmonium outcrops occasionally but more often its shifting sustain blends with the electronic sounds, perhaps spurring this rich field of harmonic interactions. The two flutes, alternately melodic and droning, in soaring glissandos, quivering vibrato, and fluttering trills, intertwine contrapuntally in stately cadences like two dancers become whole in their mirrored opposite, one pointillistic with the other sustained, one roughly textured with the other smooth, one in melodic acrobatics with the other in repetition.

Keith Prosk

Annette Krebs - Konstruktion#1 & 2 | Sah (Graphit, 2021)

Annette Krebs performs three of their own solo compositions for metal, voice, electronics, and other objects on the 59’ Konstruktion#1 & 2 | Sah.

“Konstruktion#1” - for metal pieces, microphones, voice, two sampled voices, stringed woods, plastic animals, computer, MIDI controllers, and tablet - stresses the klang and wobble of metal in clashes which emerge from a bed of silence or test-tone sines in arced dynamics like meteoroid impacts in an operatic rendering of accretion. Their shapes, especially the volume and speed around their attacks and decays, shift while sounding, sometimes sounding as if they were backwards. Planes of electronics mimicking TV/Radio static, arcade phasers, and bottle rockets intersect with sines that hasten and slow for sounds from motor whirr to click tracks. A voice enters but its shape changes too, cut and screwed into something like phonemes in lynchian delivery, keen and dumb, each having lost its meaning in losing the rest of the word. Sculpted into something perhaps familiar yet warped but always strange, the funhouse shapes of instruments and speech convey an aura of mystery even and especially when there is silence between them. “Sah” - for three sampled interviews, carbon pencil on paper, foil, parchment, plastic animals, microphones, computer, tablet, and MIDI controller - contains similar strategies of sounding and silence and altering the morphology of sounds but the sounds are now sonic drawing, the whoosh of changing spaces or opening a door, the crumpling of paper and foil and the cranking of wind-up toys whose timbres remain distinct but feel close to the clicks tracks and static of the electronics, and voices that are often first unmanipulated speaking full sentences but then wound up and spun out again, creating a chipmunk maelstrom from a room of chatter like the whining chorus of many wind-up toys released. “Konstruktion#2” - for metal pieces, their sonic reconstructions via sine waves and spectral freezings, one guitar string, microphones, two sampled voices, computer, tablets, and Arduino - is likewise similar to the first, but the metal sounds more like a faint celestial zimbelstern with the swinging resonance of distant bells or singing bowls among twinklings, the sines are now layered and overlaid in such a way to emit beatings, and the voice is lengthened a little into something like stuttering morphemes but backwards and strange again. Juxtaposing manipulated morphologies from non-speech and speech sounds in such a way - to transform speech to non-speech, to carry the origin and movement of both closer to ambiguity - draws attention towards how sound means, which might be more in the intonation of things than any contextual meaning.

Keith Prosk

Annette Krebs also recently released Konstruktion#4.

Okkyung Lee - 나를 (Na-Reul) (Corbett vs. Dempsey, 2021)

Okkyung Lee plays nine solos for cello on the 38’ 나를 (Na-Reul).

Each piece is multitracked and moments approach the feeling of an ensemble but the space remains generous, not so much through any appreciable silence as through dynamic arrangement. The pacing is generally itinerant, sometimes drifting, sometimes ambling, always going somewhere but rarely hurried. There is a variety of technique and texture but what’s striking is the high degree of pitch clarity, the ‘cleanness’ of each stroke. And the emotivity is generally not untroubled but serene, always multi-faceted, achieved through small changes in the shape of its lines, shifting meaning in its inflections. It’s difficult to determine if the titles started affecting my experience, but I found that the music reflected them as faithfully as if the theme was chosen before the music was made. The windy below-the-bridge bowings, ambiguous arco movement, and shiplike creaking strings of “Drifting.” The overlapping lines of herringbone strokes nearly tracing a mountain in articulations reflecting associations of solitude and resilience in “Mountains.” The low plodding pizzicato and heated and wild zig-zag movements that eventually dissipate like heat waves in “Mirage.” The frictional fire plow, bow pops and string creaks like crackling, and rapid and winnowing arco flickering of “Burning.” The lines overlaid to mirror each other with moments of brief beatings in “Pisces.” The tracks that are not so readily identifiable with their titles also happen to stand out in their incorporation of other elements. The extended tones of voice drawing from traditional Korean technique in duet with arco strokes in “….. (Ari).” The myriad percussive approaches forming a layered bustling polyrhythm of typewriter-like clicks, hand-drummed beats, and pizzicato repetitions. And the electronic rumble and twinkling and chiming bells of “Grey” amidst its sonorous and sad arco.

Keith Prosk

https://corbettvsdempsey.com/records/na-reul/

Maximiliano Mas - Lo que se esconde entre las notas (SELLO POSTAL, 2021)

Maxi Mas performs their own composition which explores harmonic behaviors with guitars and amplification on the three-track, 30’ Lo que se esconde entre las notas.

The components of each track are similar. A sine tone generated by one guitar, perhaps from stable amplifier feedback or ebow. Brief sequences of plucked tones repeated on another guitar, in combinations of clean standard soundings and string harmonics. And an ethereal intermediary layer of their harmonic interactions. Track “1” is particularly demonstrative in its repetition, alternating only between sequences of two standard tones and of two standard tones plus two string harmonics for its duration, with few changes to the sine tone, its relatively stable variables drawing attention towards behavioral changes in the harmonic interactions and what might have caused them in the played soundings. Like how its audibility might depend upon the duration of a soundings’ decay. How its beatings hasten and slow in proximity to soundings or proximity to string harmonics compared to standard tones. Or how its speed and spiritedness in pulse and volume appear to accrue with small increases in density through small increases in tempo. There are moments where it appears the sine tone changes, but others in which the oscillating behavior of harmonic interactions - particularly around plucked string harmonics - ripples through and is reflected in the perception of the sine tone. Tracks “2” and “3” are both more hasty and expansive in their survey of the phenomena, reversing, rearranging, and building upon tone combinations and fading and rising dynamics to activate increased harmonic beating activity. It showcases the temperamental instability of harmonic behaviors in a somewhat systematic and measured approach.

Keith Prosk

Onceim / CoÔ - Patricia Bosshard: Sillons / Reflets (Potlatch, 2021)

Onceim and CoÔ perform two Patricia Bosshard compositions for orchestra and string ensemble on the 49’ Sillons / Reflets.

The half-hour “Sillons” begins in a low-volume orchestral fog through which glimpses of coming motifs briefly appear. Antagonistic contrabass march. Strings’ siren whine. Scuffling saxophone. A brace of contrapuntal lines takes shape. The marching bass with string whine. Always flanked by the foreboding haze of a menagerie of extended techniques breathy and frictional. The music moves amongst other duets in similar scenarios as if in montage. Ebbing strings and war drums. Brass swells and scuffling sax. And these amass into a doomed and boisterous full-orchestra throb of growing density and volume exploding horns in full cry with big bass bombings and something like low-flying prop plane and the virulent swing of mingusian bellicose noir. But the swing is interrupted, faltering. And in its anti-climax the last third is a quiet dispersal.

The sidelong “Reflets” similarly begins as a cloud of strings in ambiguous movements. Its strokes desublimating into an ominous cadence with swelling volume and shifting yet merging overlapping relationships for a collective suspension of sounding to feel like an limitless looming expansion. Pyroclastic flow in slow motion. Underpinned by the beat kept by a belligerent contrabass, forcibly plucked strings thwacking against the neck. Again dissipating though closer to the end and to reveal birdsong as if these flying creatures were the only thing that could escape.

Keith Prosk

Onceim on this recording is: Pierre-Antoine Badaroux (alto saxophone); Félicie Bazelaire (cello); Sébastien Béliah (contrabass); Cyprien Busolini (viola); Giani Caserotto (guitar); Pierre Cussac (accordion); Jean Daufresne (euphonium); Bertrand Denzler (tenor saxophone); Benjamin Dousteyssier (baritone saxophone); Benjamin Duboc (contrabass); Elodie Gaudet (viola); Antonin Gerbal (percussion); Jean-Brice Godet (clarinet); Louis Laurain (trumpet); Carmen Lefrançois (alto saxophone); Julien Loutelier (percussion); Jean-Sébastien Mariage (guitar); Frédéric Marty (contrabass); Anaïs Moreau (cello); Stéphane Rives (soprano saxophone); Arnaud Rivière (electronics); Julia Robert (viola); Joris Rühl (clarinet); Diemo Schwarz (electronics); Alvise Sinivia (piano); and Deborah Walker (cello).

CoÔ is the strings of Onceim but Busolini switches to violin and is joined by Bosshard on violin.

http://www.potlatch.fr/

Han-Earl Park - Of Life, Recombinant (New Jazz and Improvised Music Recordings, 2021)

Han-Earl Park - with Anne Wellmer contributing voice - plays four constructions for electric guitar on the 54’ Of Life, Recombinant.

True to its title, it explores and rearranges material, or things whose characters seem similar though never the same, through its durations. The reverberant chime like bumped piano in ponderous cadences from the epilogue of “Game: Mutation” reappears as the foundation of “Are Variant.” More re-emerge in the half-hour title track: the gestural and illusory expressionism, with rhythms in starts, of discordant apoplectic attacks scratched and swiped in knotty plunks and chugging thunks emitting ringing and radiating harmonics intertwined with chirping picking and turnt up gain swells of “Game: Mutation;” the recurring tides of the convergence of deep bass beatings building in tempo and volume slung to a sharp singing chord amidst spacey silence of “Naught Opportune;” the whispered murmerings in cavernous textures from the end of “Are Variant.” Along with what’s kept there is always something left and something new. The country twang tune with popping harmonics from “Naught Opportune.” The unsettling mandolinesque trill or quivering sustain in hazy delay from “Are Variant.” The distorted suck, psychedelic and ecstatic, in slow crescendo from “Of Life, Recombinant.” In its representation of real-time activity that ruminates on its material, it is as if it provides a glimpse into the improvising process, whose hushed reality of painstaking practice might often be misinterpreted as something closer to strokes of inspiration out of the ether. In between chaos and composure, it is something closer to the complexity of life.

Keith Prosk

Kory Reeder - A Timeshare (self-released, 2021)

Alaina Clarice (flute), Kathy Crabtree (viola), Kaitlin Miller (harp), Kory Reeder (piano), and Conner Simmons (contrabass) perform sixty-eight pages of Reeder composition for ensemble on the twenty-three-track, nine-and-a-half-hour A Timeshare.

The goliath duration of the whole and the digestible durations of tracks prompted a piecemeal approach in me, dropping in at some point and listening to a few tracks at a time. And further sprawling its long duration across an even longer duration induced a forgetfulness in me. I might have listened - oftentimes while cooking, sometimes closely - to each part at least twice but, while I would like to say I could convey the contours of the music, I could not remember the specifics of any one part. The notes indicate an acute consciousness of the relation between the music and the timeshare in its insights and in its references to others on the inspirational material, and I think my unknowing caused by scattered half-remembrances of the music also indicates an experience like a timeshare, that those sharing it might never really know it compared to, say, a space they are in most days. It’s a rich metaphor undoubtedly with more analogous qualities, maybe even in the way people often experience recordings alone even if coincidentally. Musically it is mellifluous, gentle, spacious, reposeful. But the mood is often bittersweet, nostalgic, as if longing for a less lonely time. While there is not so much silence between soundings, their decay often reaching out to the next, it is slow enough to induce a forgetfulness in this way too. As the notes indicate, their relationships are often serial or contrapuntal, portraying those similar characteristics of the timeshare, but there are also moments of convergence and profound harmony, soundings beating together, maybe a recognition of the collective or a joyful encounter handing off the keys.

Keith Prosk

Vanessa Rossetto/Lionel Marchetti - The Tower (The City) (Erstwhile Records, 2021)

Vanessa Rossetto and Lionel Marchetti construct three environments for field recordings, synthesizers, processing, and other methods on the 71’ The Tower (The City).

Everything is a dense melange. Not so much from the layering of sounds but the number of them. Birdsong. Children playing. A skateboard skidding that might be some glitched rip. RC car or a wind-up toy. Windows notifications. Ring tones. Reggaeton rhythm. Radio and TV broadcasts in various languages. Snippets of anonymous pop songs from boomboxes or elsewhere. Children playing but now sounding like a swarm of gulls. Motorcycle revving. Muslim praises. Water. Traffic. Construction. Muzak. Singing along to a street performance of the “Careless Whisper” sax solo. Interjecting and interrupting each other. It faithfully recreates the inescapable din of cities. Maybe it is some intangible presence of space in their timbres and the contrasting proximity of them but these seemingly phonographic sounds are accompanied with what is more recognizably original instrumentation. A recurring electric thwomp and bass drop. Electric organ. Synthesizer swells. Cut and collaged voices in various languages. Electric chittering. A blast of feedback, distortion, and noise. Violin. Each of the three track appears to have its own emphasis. “The City” is more phonographic sounds. “The Tower” more voices in different languages. And “This” more decidedly musical, featuring as well a guest violinist, Anouck Genthon.

It frames the modern city as Babel realized, in which the cacophony of diverse tongues has not only defiantly built the tower but filled the city with mechanisms to multiply and amplify their noise, or maybe those very things are what made the city possible. It might raise questions on the relativity of noise and music and what variables - anthropogenic sources, language, framing, intent, others - draw those lines, the heightened self-awareness of the possibly more musical “This” with vocal references to both track and record titles suggesting a tenuous connection to music and consciousness but like the confusion and complexity of the babbling city confidently teasing meaning out of it all seems a tail-chasing task.

Keith Prosk

The Tower (The City), with more direction from Rossetto, has a companion in The Tower (l'escalier en spirale), with more direction from Marchetti.

Mark Vernon - In the Throat of the Machine (scatter, 2021)

An experimental organ record may not seem like the freshest idea in 2021, but I’ve never heard one that approaches the organ – or any acoustic instrument, really – quite like this. The difference that the label mentions is the fact that this album was made using two very unusual organs: an electric motor powered five-stop polyphone currently in the restoration process, and a custom-built organ made from over 100 salvaged church organ pipes. This pair of bizarro organs gave Mark Vernon a vast range of sonic possibilities to work with, experiment with and capture, allowing him to record a whole album’s worth of varied material that only sounds like organ music by technicalities. However, I don’t think that what’s really special here is the instruments – I think it’s the recordist.

It should be pointed out that Mark Vernon isn’t exactly known as a composer, let alone an instrumentalist – he’s a field recordist and a sound artist, and over the past decade he’s become one of the most exciting artists working in that field. But as much as this album seems like something of a departure, perhaps it’s not: to a massive extent, this is a field recordist’s take on an organ record. More than melody, tone, harmony or dissonance, the musical ingredients that might have made a Bach organ piece great, Mark Vernon focuses on the organ’s more fundamental traits and sounds: the flow of air and the reverberations of pipes, that is, the organ’s own voice, throat and body. This concept is executed in a different way in each track, allowing the album to feel like a thorough investigation of these instruments.

One striking example is “Glottic Cycle.” For this piece, microphones were placed inside different pipes to give the performance an enchanting but nauseating stereo separation. The keys were only played as softly as they could be, meaning that not enough air would enter the tubes to make them properly sound, and all that’s heard is the gentle release of air, the organ’s breath captured from dueling perspectives. Rather than the composition being something performed and recorded, it’s recorded and assembled – different recordings are made of different pipes, different perspectives, different sounds, and the composition pulls from them, arranging these soft gusts of air as if they were full-fledged musical notes.

Occasionally the album moves close to an actual performance with actual notes – such is the case on “Syrinx (active microphone studies 1 to 3).” The organ is allowed to properly and fully sound, humming a gorgeous, pulsing tone that comes and goes, rising and falling, moving through a simple musical structure that allows the piece to sound like an ordinarily composed, melodic music. The catch though is that it’s not really the organ being played, it’s the recording device itself. The organ simply emits a pure, unmoving drone, but as the recording device is swung back and forth along the mouths of the pipes the listener hears a shift in tones, the appearance and disappearance of harmonies, and the illusion of an organ with a magically modulating voice, when in fact these changes only exist within the recording device, and rather than instrumental performance we have rudimentary physical principals to thank for these shifting tones – it’s an organ composition for the doppler effect.

Another track that cleverly places its aural possibilities within the recording device is “Thoracic Fixation.” This time the microphone was placed directly in the air stream, allowing the organ’s breath to envelope the microphone and pulse around it. An effect that many would write off as wind noise becomes a platform for composition and performance as Mark Vernon picks up the microphone and actively moves it through these air streams, in full control of these windy oscillations which can only be heard from the performer’s perspective, through the recordist’s headphones. A nice idea that this album makes very clear is that recording can be performance, it’s not just a technical step in the process of releasing music. And if one is willing to consider recording performing, then I feel inclined to call Mark Vernon a virtuoso.

Album closer “Last Breath (Effets d’Orage)” does good work at putting things in perspective. Organs aren’t used at all here – it’s just a recording of wind blowing through a chimney in somebody’s home – something of a ready-made organ which nature performs. It’s beautiful, it’s humbling. As exciting as esoteric instruments are, the track reminds me to stay interested in what’s already around me, that there already exists a world of fascination within the myriad subtleties of daily perception, that to find something attractive one doesn’t always need to look further than their own chimney. That message makes sense to me, I even find it comforting, and it certainly works in this context: this is a field recordist’s take on an organ record, after all.

Connor Kurtz

Mark Vernon - Magneto Mori: Vienna (Canti Magnetici, 2021)

Ethnography is always a difficult subject in art – how can one person, especially one who isn’t even a long-term resident, understand an entire city, culture and people? And even more, how could they possibly capture and express such a thing? How could they be expected to present anything other than their own biased outsider experiences which place themselves as a fascinated observer rather than an integrated member of that community? Luckily, that’s exactly what Mark Vernon sets out to capture here: not the sounds of Vienna, but the sounds of one artist’s remembering of it.

There exist some obvious differences between memories and recordings. Memories are malleable, where recordings are concrete. Memories bend at the whims of dreams, experiences, biased conscious and subconsciousness and individual perceptions – it’s very personal, subjective processes that turn a real event into a memory. Recordings, on the other hand, are consistent – an event is heard, captured, and stored in that state eternally – well, not exactly, as Mark Vernon proves. After just a couple days of experiencing and recording events throughout Vienna on a reel-to-reel tape recorder, he cut up and buried his tapes alongside several souvenir magnets, leaving these cultural gift objects to process, erase and blur his recordings in an indeterminate fashion, and further scrambling them upon random reassembly. It’s a clever way to manipulate a tape, but it’s more than that – essentially, he created a process of experiencing and forgetting that mirrors the processes of our own brains, turning recordings into memories.

Another key difference between memories and recordings is aesthetics – where we rarely have much control over what we remember, we have complete power in what we choose to record, and how. As an artist, Mark Vernon certainly records and creates with aesthetic goals in mind, and this can be seen down to his tools and selected medium – the reel-to-reel, as opposed to a digital device which would arguably capture things clearer. There’s no attempt to hide the aesthetic concepts within these recordings, actually the incidental sounds of the tapes and playback devices are glamourized and given major roles in the mix alongside the leftovers of what was recorded. The result is, rather than a true remembering of the city, an artist’s remembering of it – one where the brain’s forgetful processes are followed, but the artist’s aesthetic instincts act as a filter along every step of the way.

A final piece to the puzzle is the addition of numerous sounds found throughout the city, various recordings of the past several decades of the city’s history and culture but deprived of any context – whether it was recorded a year or fifty ago is as unclear as what the recording even is. By infusing these literal found sounds alongside his own recordings, Magneto Mori: Vienna becomes a multi-perspectived remembering of a city – one where foreign artist Mark Vernon acts as a tour guide while fragments of the true Vienna can be heard or seen in all directions.

I’ve never been to Vienna, I’ll admit, so where the true Vienna ends and Mark’s Vienna begins I wouldn’t know. Whether this album gives a comprehensive view of the city, its culture and people, or its complex history, I also wouldn’t know. I think that might be intentional here though, because it’s a memory of Vienna we’re hearing, not an image of it. And like any memory, certainly of ones that are far from home, I should ask myself – is that really how it was, or is that just how I remember it?

Connor Kurtz

Thank you so much for reading.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you find yourself spending a good chunk of time reading the newsletter, discovering music you enjoy in the newsletter, dialoguing your interpretation with those in the newsletter, or otherwise appreciate its efforts, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the writing team, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of a project it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians $0.78 to $3.15 for the month of October and $2.00 to $5.32 for November. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.