1/13

conversation with A.F. Jones; notation from Cheryl Leonard; reviews

IM-OS recently published Issue #8 (Spring 2022), with a focus on open scores for large groups of improvisors and contributions from Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen, Carl Ludwig Hübsch, Una McGlone, The Noisebringers (Maria Sappho, Brice Catherin, Henry McPherson), and Etienne Rolin.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate this newsletter and have the means, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the regular writers but the musicians and other contributors that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the regular writers, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of work it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians and other contributors $1.99 to $4.64 for December and $2.90 to $7.74 for January. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

A.F. Jones is a mastering engineer, sound designer, composer, and performer based in the Pacific Northwest whose experience in acoustics and audio engineering informs his musical practice and vice versa. Over video chat we talk about mastering, ethics, phonography, ecology, and musicians’ grind by way of Marilyn Crispell.

Alan is the chief mastering engineer at Laminal Audio. He also operates the Marginal Frequency record label, which has recently released untitled (2020) from Francisco Lopez and Final Embers of Sunlight from Necking. Alan himself has most recently released pirate evangelism with Gabi Losoncy and has a new release coming soon of his duo, what, with Dave Abramson (Seattle, WA) on Eiderdown Records, entitled the unconscious is a machine for operating an animal. His film with Bob Burnett, “What Is Man and What Is Guitar?,” about the legendary Keith Rowe of AMM, continues its festival run and will be available soon in subtitled form for Japanese-language audiences.

AJ: Keith! Can you hear me?

KP: Yeah, can you hear me?

AJ: Yeah, I can hear you. I can see your face too.

KP: Oh, perfect. There you are.

AJ: Yeah, hey.

KP: How’re you today?

AJ: I’m good. How’re you doin’?

KP: Nice. Doin’ alright. It’s actually super cold here right now, which is unusual in November for us.

AJ: Oh yeah? What’s the temperature there?

KP: Uh, it’s only around 50F outside but we’re kind of wusses and anything below 65F brings out the sweaters so…

AJ: It’s cold, so cold. It’s good to see your face. We talked on the phone a few times, this is even better.

KP: Yeah, yeah to actually kind of get some of the body language cues going with it.

AJ: Yeah, yeah like that [flapping hand] body language.

KP: [laughs] yeah, slight movement of the shoulders, yeah.

AJ: [hunches and groans]

KP: [laughs] but yeah I’ve got a couple threads of things that I wanted to hit up but always feel free to take it in any direction that you want to as well.

AJ: Sure. Thank you.

KP: Ready to get started?

AJ: Yeah, absolutely.

KP: Cool. So one of the things that I’m kind of interested in is learning about some of the mechanics around music, whether that’s organizing or running a label or other stuff. So since you run Laminal Audio for mastering I wanted to start off with what is mastering to you?

AJ: Yeah, that’s a good question. Really what it comes down to is what does the music itself need in order to be heard the way that the artist or the musician needs it to be on the final medium, be that streaming content or on vinyl, cassette, or CD, whatever. And so I kind of work as… a friend of mine calls me a midwife for a lot of musicians and I chuckle at that but I accept that. I like having that responsibility, which is a big one. It’s a challenging one. But it’s also one that I feel I’m pretty good at, walking a project down it’s final couple of processes to where it’s going to finally be on some kind of medium to exist forever and ever. So, it’s not really a technical answer, but it’s certainly a driving force behind why I do it and what gives me more kicks about mastering than any other part of the production process. Ensuring that the music meets the technical requirements of the medium while maintaining the aesthetic requirements of the musicians. Advising is sometimes the case in the area of music that I like to work in. Which I guess you could say is pretty far out there, abstract, most often not based in things like metre, cadence, any kind of tonality with respect to scales... more abstract kind of music.

KP: mmhmm. You mentioned different formats; I understand that there’s maybe a different approach, say, for digital and CD versus LP or maybe even tape. Do you have to navigate those, the capabilities of the medium as well. I guess mediating for the medium...

AJ: Yeah that’s one of the entry points to discussion when going into a project with someone, is ‘where do you hear this being or what has the label decided is going to be the ultimate format?’ Most of what any of us do these days is digital in some capacity. There are very few services or studios out there that offer a purely analog, start to finish, kind of process. While I have the capability to do everything in analog, it requires that I first receive tapes, rather of pristinely resolved digital mixes at the highest resolution possible. You transfer the audio from tape through processors and unique signal chains. Ultimately what you end up with for just about every label that’s in operation is in some sort of digital form, even when mastering in analog. You get the highest resolution off of certain types of digital files formats, so I master to those, at whatever the native resolution is that the mixes were sent to me. So those then become archival masters, which are the basis for anything that you would ever do with them, be it stick it in your archives or if you want to modify them ultimately for vinyl. I don’t make aesthetic decisions in mastering, that’s for the musicians to make those decisions. I work with them to realize those aesthetic decisions which are ultimately realized in digital form. When you get to the stage that the masters are being prepared for cassette or vinyl, there are certain adjustments that are going to need to be made to that final digital form in order for it to sit comfortably on the analog medium. And this has a lot to do with imaging, certain frequency bandwidths, amplitudes in higher and lower regions and more. Once all adjustments are made I communicate with them, letting them know that every one of the requirements have been met. Communication can be either through the label or through the musicians or directly with the cutter in the case of vinyl, depending on who the client is. In the case of vinyl mastering my objective is to relieve the cutter and the cutting engineers of additional work that could, in worst case scenarios, alter in some way the intent of the musicians, say in how high they wanted certain frequencies to be and sit against everything else in the mix. Does that help?

KP: Ah yeah, of course.

AJ: Good.

KP: I know some musicians can have a hands on or hands off approach, but do you encourage any particular approach, or what does the collaboration with musicians usually look like?

AJ: You can usually tell in the entering discussion but, usually there’s an inquiry about how far they are in the process, all the way out to naming titles. I mention that because sequencing is incredibly important, at least for me. I go into a musician’s recording not expecting to just get knocked out by one track and just go to that one track over and over; I want to listen to the entire album. And the expectation often is that the musicians or the composers have sequenced the record in a certain way that it plays almost thematically, like an album. Sometimes that is not the case, so I don’t always like to assume that. I like to have a little bit of discussion about the musicianship that was involved, if there are other band members or musicians or soundmakers that were involved in the process, and then we go from there. Often it will start with me taking one track, sometimes it’s the most difficult track for me to attack because of different types of events or episodes that are happening across a long piece of music with a lot of dynamic range to it. And those are the ones that I’ll like to jump into first and then send it back to the musicians for their takes on the direction I’m going in. And I may give them a little bit of instruction if needed on the best place to listen if necessary if there’s a lot of bass or subregion, just that kind of discussion. And then usually it’s a thumbs up. Sometimes it’s not, little tweaks are made here and there, we make it through that, and the nice thing about this process is that it kind of sets the tone for the whole communication process throughout the whole project. And it gets pretty easy from there.

KP: And just since you mentioned instructions for environment, is your listening environment usually over the ear or in the air?

AJ: Oh, in the air. I also do what I call a forensic kind of listening, which definitely requires headphones, because I like to listen for maybe splice points that are happening that the musician or the mixing engineer maybe didn’t get to or they couldn’t resolve somehow. I like to listen for those points, make notes of, “OK that’s definitely going to require some treatment,” beyond the basic parts of mastering like eq and compression. I make notes of those instances through headphone listening. But really what I first like to do is just listen in an open room, be it in my living room on my listening system that I like to listen to just about anything on or in a more sterile environment like here in the studio and just go through it and capture my own thoughts about it and ask questions as needed.

KP: Yeah. So I’ve heard - I’m not quite sure if I have the ear for it - but I’ve heard people say like, oh the music was good but this was a bad master. So how might the listener perceive the difference between a good master and a bad master, or a master done with care versus one that wasn’t mastered.

AJ: To me that’s a stretch. I hear that language quite a bit and having sat in this chair now for several years I don’t know that I’ve ever been on that end of that kind of criticism, at least that I know of, but it’s certainly possible. But being in this chair and having I guess the requisite amount of empathy for the so many hands that can be involved in this process…. how does one come to that conclusion or make that judgement? Because saying something is a bad master, that’s assuming a lot of knowledge on intent, and the intentions specifically of the musicians, because they do have the final say, always with my technical concurrence. But yeah that makes a lot of assumptions about the intentions of the musicians themselves, the record label, the mixing engineer, the mastering engineer, about that entire process. So I don’t know.

I can think of one example. I don’t know if I would call it bad but say like, that master is questionable. And I was listening to it just the other day and I remember there even being some discussion about it on message boards where a lot of casual listeners came to the same conclusion about this one recording. It was the Anthony Braxton Quartet, and I think this was the Mark Dresser days if I’m not mistaken, but it was Live at Yoshi’s In Oakland and the album, the CD itself is incredibly quiet. And that was the one point of feedback that everybody including myself kind of discussed at that moment back then, kind of agreed about like, yeah you really have to turn up your headphones or your stereo to get it at the level of presence as you would most CDs. Now I know that that was, number one, that that was the responsibility of the mastering engineer in such situations to get those levels where they need to be. Also what I’ve learned is that it may be jumping to a bad conclusion, the intentions of the mastering engineer. The mastering engineer may have had it completely correct, it got sent off to a CD pressing plant, who knows what plant they use - by the way that’s a crapshoot in today’s environment, which is pretty saturated - but they sent it off to the pressing plant and the pressing plant levels were off, maybe they had a 6dB pad on their final output channels onto the CD or something and it made it that way. So it’s kind of hard to say it was a bad master or not. It certainly was a print that didn’t meet the requirements of what you would expect from even classical music levels, right.

KP: Yeah, was this the ninetet recording?

AJ: No it was a quartet.

KP: Oh right, you said that, my bad.

AJ: That quartet, you know, Gerry Hemingway, Marilyn Crispell, I’m trying to remember what year that was, it’s been a long time, ‘92? I can’t remember.

KP: Yeah, I don’t know if I’ve heard that. I remember the ninetet at Yoshi’s was late ‘90s, early ‘00s or something.

AJ: Yeah. But it’s good. It’s an amazing record. And by the way if you turn it up you’re not saturating it or anything, you’re just turning it up to good levels and it sounds really really great. It’s one of my favorite recordings by that quartet, yeah.

KP: Oh nice. OK. I’ll have to check it out. I’m a Braxton fan as well and listened to some of the like ‘85 bootlegs and Willisau and Santa Cruz but I didn’t even know about that one. So much Braxton.

AJ: There is, there’s a lot.

KP: I guess since you’ve been mentioning intent and aesthetics and maybe trying to shy away from having a little aesthetic input but is there an ethics around mastering or critical perspectives around mastering or decisions that you have to navigate?

AJ: Quite a bit. And what can make it challenging is that expectations vary from one musician or composer to the next, as does experience. You know, you may have a well-renowned musician whose reputation is evident in all of their works that they have on CD and vinyl or whatever but they come to you and it’s their first time ever working directly with a mastering engineer because they’ve always had the label doing it for them, taking care of that process for them. So you are seeing a different set of expectations from that person, between them and someone else who might only like to work directly with the mastering engineers because they like to be in absolute control of every part of the process and truly be the final person to sign off. So the ethics therein are very simple, you know, it’s having some respect for that and having an understanding that every situation is going to be different and doing a lot of listening to what someone is requiring of their work.

KP: I wonder in your practice, that doesn’t necessarily deal with people a lot but environments and animals, what kind of considerations you’re making, or are there ethical issues that you’re aware of whenever you’re doing your phonography? For instance, with your AMPLIFY 2020 piece, the Bainbridge site, it’s a sensitive topic, right. So I guess whenever you would be putting together something like that, what decisions are behind what you’re doing to give it the respect that you think it requires? Or likewise how do those situations maybe translate to the video you shared where you’re recording salmon? What are those kinds of decisions behind your different phonography processes?

AJ: There’s a lot of appropriation going on in people’s music, whether it be outright borrowing to theft to virtue signaling through a person’s art. Those are the kinds of things that I think about when you ask about ethics in one’s own work. I didn’t have to think too long about the project that I did at this memorial on Bainbridge Island here in Washington State, which is a memorial dedicated to Japanese-Americans who suffered through the whole internment process. Number one it’s a beautiful site. There had been probably two or three years that I had in mind, wouldn’t it be cool to go out to this place which is pretty remote, it’s away from a lot of anthropogenic noise or man-made noise, and just feel that space out acoustically. The opportunity came by way of AMPLIFY and foremost by way of the pandemic because that place was barren just as any other place was in the month of March in 2020. So I can’t imagine being able to do this today where you would go out to such a site and not see another human for the entire three hours that you’re out there. Just uninterrupted solace while you’re there. Which allows a lot of free-thinking and choices to be made, about how you want to record the piece and then, in the post-part, about how you overall wanted it to be produced. So the decisions I make are sometimes thought out on a internal spectrogram, from 0 to 30,000hz, which, if there are interesting enough things in just about every possible bandwidth - you know, the lows, the highs, the high-mids - do what you can to capture those. Probe around for a different positioning of whatever capturing device or sensor that you’re using. In this case I was using open-air microphones and a geophone - which is a seismic detection device that’s been retrofitted to record - audio and contact microphones and a stethoscope mic. And sometimes a repositioning of any one of those things by just a centimeter would result in different timbres. Having three hours in that spot, to walk around and probe around on different parts of an iron gate or a big slab of concrete or jade through which a distant ship horn was transmitting … because the medium of the jade or the stone was between the origin of the sound and the receiving devices, you know, probing around with those things I was able to bring home with me a whole lot of options. And then the composing part of it came very quickly. It had to say one thing specifically in an episodic type of format to which anybody’s imagination could be applied and maybe take something away with on their own without being too deliberate with what it was that you’re trying to record.

KP: So whenever you are doing ecological recordings, what are some of the considerations that you have to make there?

AJ: I spent a lot of time documenting a salmon stream and the local ecology in the riparian area in a place called Port Orchard, Washington. In what a lot of people call field recording there’s always the potential that your recorded information can be sent off to the science community or to undergrad or grad students at Washington State University for their bioacoustics department to chip away at. The idea is to have recordings that best replicate the environment that you’re in and that you’re trying to document by way of audio. You are considering post-production even as you are recording in real time. And physical boundaries not unlike the type of filters that you might use with a camera or f-stop settings or whatever. Often you end up with something - all this goes into an archive - that is just so unique and sometimes maybe even unidentifiable in terms of its source and you may or may not be inspired at that time to use that as the basis for a larger piece of music that ends up in a compositional work or improvised recordings. This is the way I like to work most of the time.

KP: Is there a threshold between the arts and the sciences for this kind of recording work?

AJ: If you’re talking acoustic ecology, I don’t see one. I see debate about what it is. And it’s necessary debate. But as far as the threshold, not so much. I once recorded a ferry that was pulling into port in Port Townsend, and this was in the context of raising awareness for the gray whale population that lives up in that area, and it became a good project for me to get out in front of people who might be willing to listen to that type of thing and read about it, noise pollution. I kept no secrets about how the recordings were obtained or what the actual sounds were… in fact I wanted listeners - ideally after the fact - to be able to read through what is happening in linear time over the process of this recording. And what you learn while listening to it is that a ferry’s propulsion train operates in different modes and one of them, which is its most commonly operating mode, is extremely loud. Especially when the propulsion train - which is the propeller, the shaft that goes into the inboard part into the engine room, and the engine room itself - if those things aren’t maintained very regularly - to the degree that fishing nets or rope or steel cables ends up around the propeller - it can raise decibel levels by about 70dB at their worst, compared to what they would be if they were properly maintained. Well that additional noise that gets put out by the ferries when they are not properly maintained - or any fishing vessel or seagoing vessel for that matter - has disastrous effects in the marine community, particularly with marine mammals and their prey species and the prey species of the prey of marine mammals and so on and so on. So I wanted to be very up front about exactly what those recordings were. It turns out that after the fact - to my ears at least - there’s some very musical aspects of that recording which gave me kicks as well. So it kind of tickled both regions of my own interest in that one little piece.

KP: Yeah I feel like I have read about not necessarily that project but the effect of anthropogenic noise on whale populations and I think it has some interesting implications for humans, right. Like humans that are living in very noisy cities and humans that are living in less noisy rural areas and what psychological effects those may have. I think I was kind of interested in the science and art threshold question only because I feel like there’s a boundary of rigor, where maybe whenever you’re coming at it from an aesthetic point of view, maybe just capturing it once causes that inspiration but coming from a scientific perspective you usually want a data set, right, something that you can run some statistical analysis on and find some throughlines, some trends. And I feel like the arts thrive on ambiguity and you can’t have that in a scientific process, you have to be very clear about what your methods are, what your biases are, the processes you took to combat your biases.

AJ: Yeah it all comes back to the intent of the work, I think.

KP: Yeah yeah. Say, if you were to have a scientific data set of say fish sounds or something to the right ears it can be very musical...

AJ: Yeah and I suppose if you’re inclined to listen to it that way, right. I’m sure there are those in the science community that heard nothing of the sort. That heard nothing goddamn musical about it [laughs]

KP: [laughs] they just run it through a program and look at the frequency ranges or something... I don’t know, I guess any documentation is important. In your communication with the scientific community or even just on your own, have you found something that sonic markers can convey that maybe other markers can’t, like population studies or visual markers?

AJ: So you’re talking about something that is very important to me right now which is noise pollution, effectively. And what I’ve learned in the process is there are too many hats to wear to solve the issue. Focusing on what you’re good at and why you’re doing it and the why you’re doing it will reinforce the product. And in this case, for me, it’s recording. It’s having very specific ideas or at least a specific framework of ideas to go out and record a site or things within a specific site that is out there in the world. It’s not just, “oh I hope I can get some really cool sounds out of this building.” There can also be a secondary purpose, such as having those recordings on hand for others who might need it for their work or my own work in sound design, for working in film. The too many hats part comes in when you’re getting too deep into… “oh shit that’s a spotted owl, I thought there were only barred owls in this region, I wonder if this is a protected area.” And it’s a very satisfying path to go down. And then, “OK that definitely was a spotted owl because of these timbres and because of these rhythms and percussive kind of sounds that were at the trailing edge of its call. Oh that was a mating call or just a ‘I’m here’ kind of call.” But ultimately that is just functional knowledge of an environment, which can be very useful in your own empathy for the environments that you’re operating in. When it comes to the bioacoustics aspect, that’s where it’s important to link up with other communities, the people that nerd out all day with their own software suites that bioacousticians use and see what they can pull out of the recordings and add that to a map or an archive for a specific area for a project that may or may not be going on, and determining for instance how development or capitalism at large is affecting semi-rural to rural areas that are miles down the road. The work that recordists can do if they come home not too thrilled about their day out in the field is to hold on to that and work with communities who might be able to use that material for something else, something even bigger than realizing our own artistic projects.

KP: Yeah, and I imagine even recording the same space or a similar space across time can be super helpful as well. I mean you get a sense of seasonal behaviors of what’s there but you do also see longer term effects in the context of developments and stuff like that.

AJ: Sometimes the difference makes itself most apparent just by the times of day that you might be recording it. When you zoom out and start comparing recordings that you’ve made of a specific area over the course of a month, things begin to get even more interesting. And then exponentially so if you’re recording a site for as long as a year or more, hopefully with others helping you out.

KP: Yeah. How long have you been doing the creek project?

AJ: That partnership started I think two years ago. It’s an organization out here called the Great Peninsula Conservancy. One of the stewards over there and I just happened to meet and talk about things - she may have read something or vice versa - but we ended up talking and we both got pretty jazzed pretty quickly about the potential in me being able to just do stuff that I normally like to do on such an outing with microphones and have it be useful. And where this has really become special to me is in the ability to teach young people and to get them into this type of thing. So I’ve done a couple of lectures with middle school students about this whole idea of getting out and leaving the camera at home and just take microphones and a recording device and see if that kind of thing gives you kicks. All the way out to encouraging them, encouraging a seventh grader to work with the academics and researchers about the things that they’ve been recording and starting conversations about whether or not this could be useful to those departments at schools or any particular student who might be doing a project. A nice feedback chain can sometimes develop out of those efforts and that makes me pretty happy. I get to, on Sunday, provided the weather behaves, do like an hour and a half walkthrough of this specific site, the Curley Creek, where the salmon do their annual runs and walk people through the processes that I took out there, how I went about it. And how do we protect it? How do we conserve a place like that? And furthermore how do we restore similar areas that have not been so cared for or that have been completely beat up, particularly just in the last four years by administrative changes and funding changes to wetlands conservation efforts and other environments.

KP: Did I hear that that particular area was dammed?

AJ: It’s not. It’s actually a tributary that feeds directly into the Puget Sound on part of the peninsula out here called Port Orchard. It’s a rural part of that town. Dam removals are something different and that’s where I think I’m going to be spending a lot more time over the next year, trying to work with others on a long-term project. You’ve seen satellite photos just of your town or Round Rock or Georgetown or places like that, what they look like in 1955 versus 2005 and the comparisons are crazy, right? Just the amount of development. I want to do something similar with audio and work with other recordists and any students in ecological programs - and I’m talking ecology proper not acoustic ecology - who might want to partner up and do before and after recordings of the areas down near the Snake River and the Klamath Basin in the northern part of California where four dams are actively being discussed for removal.

KP: Yeah there’s a book - I’m blanking on the author, I think it’s John Graves [it is] - called Goodbye to a River and it’s about his last canoe trip down - blanking on the river too but I wanna say it’s the Blanco [it’s the Brazos] - before they put in the dams. And in the context today, after having put in the dams, it’s pretty sad. Just what it’s done to the experience around there. Some of my early background is in river geology so I’ve got a little knowledge of what dams can do to a watershed and how just putting in a dam completely changes the way a basin erodes, where the runoff goes, so it’s not great.

AJ: No it’s not.

KP: And then you’ve got the whole US Army Corps of Engineers thing - which is I guess is mostly active in the Mississippi - but how they treat the river like a sandbox and put in random shapes to see what they will do. But yeah it’s… I don’t know… I feel like the way the modern US culture treats rivers is a little disrespectful I guess, trying to control them a little too much and not really aware of the effects they cause when they play with them.

AJ: Yeah a good study is the Elwha River.

KP: mmm, where’s that?

AJ: It’s in northern Washington, it’s up in - I think that’s Jefferson County - but it’s north of the Olympic mountain range on the coast of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and there were two dams there that were constructed 100, 120 years ago, something like that. They took the dams down in the 2013, 2014 timeframe if I’m not mistaken. For the first time in a hundred years, right. And what they have seen, with the removal of the upper and lower dam, miles away upstream from the mouth of the river, is the return of King and Chinook salmon, which have not seen that part of the river in over a hundred years. What they’re finding is that marine-based minerals that are carried around by the salmon -- because they have spent so much time in a marine environment -- they’re transporting those minerals, things at the molecular level, that far upstream, which has additionally boosted the return of even certain flora up there in riparian areas. Certain predators are returning to the areas which brings certain consequences or circumstances in addition to the salmon and what they bring and what they deposit into the river. So you’re just kind of at the micro-level seeing this slow shift to what I think many imagine things might’ve looked like a hundred years ago when there was zero building on that dam where it was just used more or less for logging. And that’s very promising to me. The same level of concern - as much as we have concern for the local ecology itself - is in indigenous communities, specifically in the area that I’m talking about in northern California and southern Oregon in the Klamath Basin. The dams and drought have put a damper on indigenous communities and their ways of life, which in many areas on those rivers are built around fishing and specifically for salmon. When you have the amount and the level of fish kills that you’ve seen over the last couple of years, just because of drought conditions and other untoward events, it’s having a massive impact. It gets interesting because, as much as it is a right for indigenous peoples to have their quota, which is effectively - you know it depends on where it is and it depends on the state - limitless, which is good and how I think it should be, under a responsible fisheries management program, right. But there’s competition by local farmers, right. And there’s competition not just for the fish by local fishermen that do make some income off of fishing those rivers but also the farmers themselves and the allocation of those waters. When the waters become so low because of the dams that still exist - that really do very little these days comparatively when you have other power sources such as wind - you can imagine how nasty those discussions at a political level can become, especially in local politics. It’s interesting to watch.

KP: Yeah, I almost actually forgot that dams can be used for power [laughs] I mostly think of them as flood-control measures. I’ve got some odds and ends, those were the two main threads I had, but do you want to take it in any direction in particular?

AJ: I am having a good time doing a lot of listening lately to a lot of records that I haven’t listened to in awhile and also going through some interviews that I’ve done… I think you read this thing that I published with Marilyn Crispell at the beginning of the week?

Read Alan’s interview with Marilyn Crispell here.

KP: Yeah, that was super interesting.

AJ: Man, I don’t know, and maybe I’m showing my age or something… I’m just, I’m missing those times. And not in a way that “things were better back then or it wasn’t like this 20 years ago,” I’m not processing it that way. I’m processing it with all of the frustration that is being endured by so many musicians and people involved with music and the arts in general. There’s a lot to be taken from in some of those discussions that happened 20 years ago and it’s remarkable how different things were just in terms of the grind itself, what it’s like to be a musician and what collaboration looks like and what good curatorial decisions look like, those types of things. And digging back into some of these interviews that are 20, 30 years old, it’s been really illuminating for me lately, both as a musician who at times does his own thing and as someone who’s just involved with other people’s music.

KP: It’s interesting that you say that you felt a lot has changed because when I was reading it my thought was, wow it seems like not a lot has changed [laughs] only because y’all were talking about like, wow wouldn’t it be nice to have a national healthcare system…

AJ: Yeah, the concerns are definitely the same. I guess they’re just in a different kind of shape and paradigm at this point. I guess the one thing that I’m thinking about that I’m not articulating very well is just the outright saturation that exists now versus 2001. Which is, it’s something to digest.

KP: Promotion. Yeah, promotion was another thing that stuck out. If we could only get people to talk about this music there are people out there who would listen to it. And yeah, maybe compared to 2001 with the web a little more fleshed out there are presumably more voices talking about it in maybe a more accessible way through the internet but not compared to the amount of work that’s just available. And then I guess another interesting thing that stuck out to me is... Marilyn says something along the lines of, we are the product of our contingencies. What she was listening to, what she was doing at the moment, what she’s experiencing, which is very intuitive and it’s something that I agree with as well but I know she was a performer in a heavily improvised context but it’s nice to have a performer’s voice acknowledge that instead of like, there’s a right way to play Bach and there’s a wrong way type of thing.

AJ: Yeah, she’s such a sincere and warm voice too. She’s just immediately… I don’t know, just immediately inspirational in what she has to say.

KP: Yeah, she also said too… she seemed very concerned with the well-being of the people around her, and I think that came through just in y’alls conversation.

AJ: Yeah, yeah, magically so, huh. I have a good memory of the first part of that interview, I think the March 16th part. But all of that, that was like two and a half hours of me sitting in my automobile in my garage because my kids were real young then - I think they were two and four years old - and it was their bedtime and I was like, there’s no way I’m gonna be able to pull off a telephone interview I’m trying to record in the house, so I went out in the car. And she made it the coziest place in the world to be during a cold March evening in 2001. It was a wonderful discussion. I think we’re all lucky that she wanted to open up so much.

KP: And you mentioned Braxton a little earlier and I got a sense that you at least used to listen to quite a bit of jazz around the time of this interview. Do you still or?

AJ: Yeah, yeah. Absolutely. There’s a lot of new jazz that I’m finding my way into and then there’s also some of the old jazz which is really what informed all my listening and even my playing right now, the way that I improvise more immediately comes from someone like Ornette than it does others that you might think if you’ve listened to my work. More that, in the course of improvising, I’m talking specifically with live performances, just the manner of composing something in real time either by yourself or in collaboration with others, big imprints have been left on me by people like Thelonius Monk and Ornette and certainly Marilyn Crispell in how I might think out the trajectory of decisions in a live performance. But yeah I’m heavily into jazz, I would be embarrassed to say how many jazz recordings that I have, right. Tyshawn Sorey is… he’s a fucking genius. In today’s music, for me personally, he’s at the center of a lot of things with his thinking and his composing and especially with his playing. He’s a monster, on a lot of instruments. I’ve been really into him and his work and some of the satellite works that have been popping up around that sphere.

KP: Nice. You mentioned that you’ve been spending a lot of time with records; what else have you been listening to lately?

AJ: A lot of older records. A lot of CRI recordings, do you know this label?

KP: mm mm

AJ: Composers... Recording... Inc? It’s very university, academic based effort, this label, that existed I wanna say from the late sixties all the way out to maybe ‘81… [It was 1954 – 2003] But these recordings were full of American composers and occasionally composers from overseas that were doing fantastic, near outlandish type of work in the composing world. What I would call experimental composition. Cagean in many ways. In other ways more influenced directly by Feldman than Cage. But there’s hundreds, I believe, of releases on that label, with all kinds of juicy little kernels of activity that you wouldn’t find elsewhere, names that you wouldn’t hear about elsewhere. Sometimes these recordings... were completely driven by a faculty head in a department of music using a couple of students that might’ve been available to them, and then some big shot symphonic orchestra level chairs that are playing and adding their voices to this music too. And in other cases it’s just completely obscure. You know, musicians and composers who now have an enduring place on this label. I wanna say that New World Records is beginning to release or re-release some of those CRI recordings.

Explore New World Records’ reissues of CRI releases here.

KP: Yeah, whenever you described it, it seemed like a very DRAM type of thing, which I think is tied to New World too. Alright, did you want to hit up anything else?

AJ: I should mention some collaborations that I’m working on. I really respect the people that I’m working with just out the gate but they’re such nice people and they’ve been very understanding with me and this stop-start constant thing that’s been going on with me since mid-2020. One is with Alexandra Spence. She’s Sydney, Australia based. We’re at the beginning stages of a project that we have kind of teased back and forth with wanting to work with one another for a couple of years and we’re finally in the beginning stages of that. Grisha Shakhnes and I started a project in early 2020 and we’re nearing the end of that. The collaborative continues in kind of real time phase and we’ll be in post-production on that at some point. And then also a British player by the name of Daniel Jones whose the biggest sweetheart of a guy and someone whose work I was turned on to many years ago. We rapped with one another one time about, you know we should do something together. The results have been joyous for me. I’ve loved working with Daniel Jones. And the greatest thing about Dan is his humility which if you know him you’re laughing with me inside right now because he is humble to a fault which is what makes him so great. But yeah, he sent me some really interesting work that I was able to work back with and we’ll be picking up the final stages of that at some point pretty soon. Grisha Shakhnes and I have a project that has required some environmental aspects to line up properly in order to execute the ideas. I want to say we are nearly completion on that one, which we’ve thought about for a long time. Lastly I’ve begun mixing the new Telescoping record, which is myself, Dave Abramson, Greg Kelley, and Rob Millis. We are working from around two hours of material from live recordings we made last year in a bizarre space, physically, aesthetically, and acoustically. Those are all things that I’m working on right now. No solo stuff. Haven’t been in that headspace. And rather putting any pressure on myself to be in that headspace I’m just enjoying working with others right now.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Cheryl Leonard - Point Eight Ice (2011)

Cheryl Leonard is a composer, performer, field recordist, and instrument builder perhaps most associated with the natural-object instruments she crafts from bones, stones, shells, wood, and other found natural materials and the non-standard notations she composes specifically for these instruments, often in tandem with field recordings and reflecting the environment(s) the materials came from. In 2021, she released Schism for field recordings, coil pickup recordings, natural objects, glass, and metal.

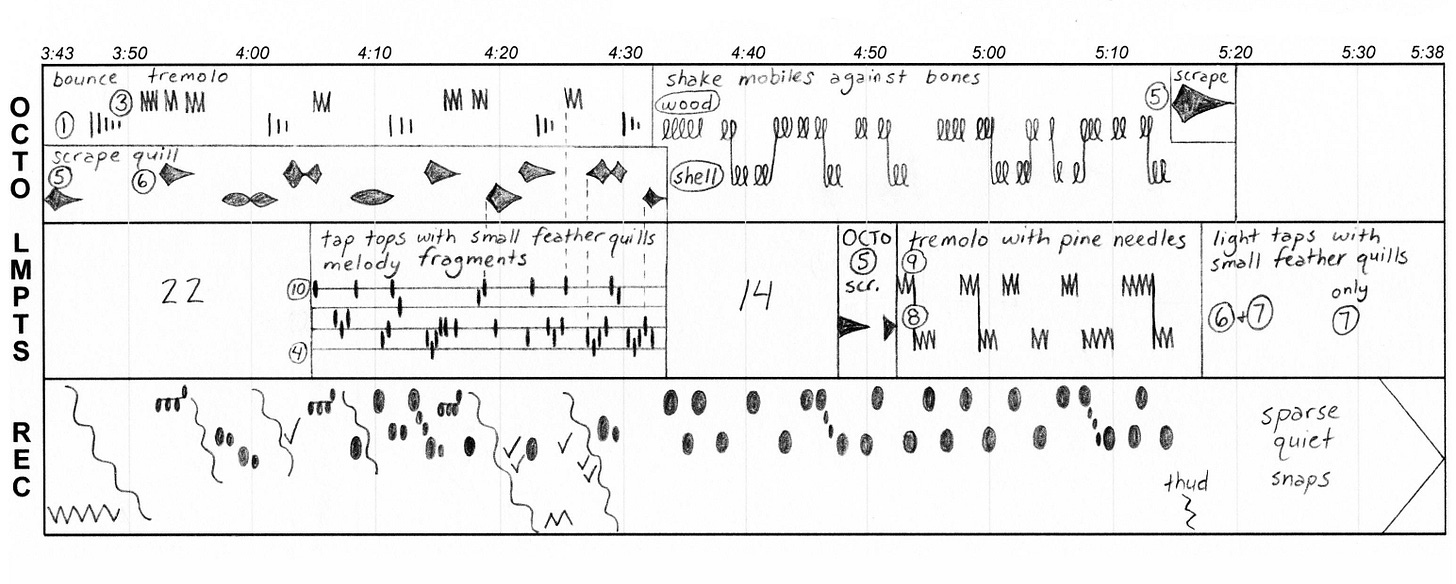

Point Eight Ice is a 2011 composition for two performers with Octobone, Limpet Shell Spine, and a fixed field recording. It is part of a project, Antarctica: Music from the Ice, created with natural objects and field recordings sourced from a five-week trip to Antarctica’s Palmer Research Station. Raw sounds from Leonard’s trip have been released on Chattermarks: Field Recordings from Palmer Station, Antarctica, and an album of her musical compositions is due in 2022 from Other Minds Records. Point Eight Ice features its three parts together in a diagram on an absolute timeline. It includes: circled numbers for location on natural-object instruments; floating numbers for silences; text direction for action; indicators for dynamics and tempo; and various drawn shapes for tones, the heights of which indicate volume and the vertical position of which indicates relative pitch. A performance from the composer is below.

The shapes intuitively represent the gestures described by the text in time: loop-the-loops for the nearly rotary wrist motion of jingling mobiles; zig-zags for the seismographic shaking of tremolo; points for taps; and lines for scrapes. I think it’s interesting that traditional dynamic indicators are used for a mobile and feather flicks in the first 30” when shapes and their heights are used for similar devices elsewhere. Drawing out the fixed field recording seems to illuminate a desired relation to the performed sound, like the percussive compliment of quill taps to loud pops around 1’00” or a contrapuntal interweaving around 3’10.” The text associated with the fixed field recording describes the sound result while the text associated with performance only describes how to make sound, which makes plain sense because the recording already exists but also implies an openness in the sound result and centers the contingent performance aspect of the piece. The performance above breaks the score beyond the indicated ‘improvisation’ inherent to these fine movements by realizing it with a single performer alternating among natural-object instrument parts with playback and by using a vertebrae mobile instead of pine needles on the Limpet Shell Spine around the 3’ mark. While every mark on the page is understandably not reflected in this performance, the performance does demonstrate the precision in dynamics and relative pitch possible with these instruments, whose non-standard tunings require non-standard notation like this.

reviews

Joshua Bonnetta & Judith Hamann - RE-RECORDER (Canti Magnetici, 2022)

Joshua Bonnetta and Judith Hamann explore film sound design via contact mics, electronics, tape, synth, field recordings, cello, and voice.

Last week, I finally watched Edward Yang’s multi-generational family-drama epic film Yi Yi, in which ‘nothing happens’ but also ‘everything matters,’ in the sense that everyday images and sounds take on a kind of spiritual significance via camera and microphone. What is it about film as a medium, or perhaps even visual media in general, that so readily supercharges the banal in this way? Something in the shot, something outside the shot? In RE-RECORDER, it is not only the obvious absence of image but also the absence of concrete narrative, the absent ontological ground against which to feel that numinous spiritual connection, which is experienced as a haunting - a melancholy inability to find ‘real’ coherence in this assemblage of “location recordings, musical fragments, foley, in-studio recordings, outtakes, and sketches,” not knowing how different situations have been pasted together or modified (why am I tearing up listening to traffic, is it something in the mastering?). Of course these issues are not different from issues in ‘real’ film, which also can provide only an artificial coherence. Still, in suggesting the ‘removal’ of a visual element which was never really there, Bonnetta and Hamann construct a sensibility according to which, it turns out, the images were only a distraction. Here, in sound alone, is both a hardening and a softening of awareness, and new dimensions to explore.

- Ellie Kerry

Vilhelm Bromander - aurora (Warm Winters Ltd., 2022)

Mauritz Agnas (clarinet, contrabass), Emma Augustsson (cello), Vilhelm Bromander (soprano saxophone, pump organ, percussion), Johan Graden (clarinet, piano, pump organ), Anton Svanberg (tuba), and Pelle Westlin (soprano saxophone, clarinet, bass clarinet) perform ten Bromander compositions on the 26’ aurora.

Tracks’ fleeting brevity adds to the airiness imbued by the instrumentation and that each almost appears a variation on a theme adds to the dream haze of the flighty tracks. Small nuances differentiate them, organ and tuba accentuated here, twinkling mallets and cymbal splashes there, some step-pattern play, or a prominent pause, melodies coalescing into lush layered harmonies with saccharine apogees. Hear children playing in the rests. Its harmonies push and pull for separate and synchronous emotivities, at once low and hopeful, elegiac jubilations, a cordial malaise.

- Keith Prosk

Eventless Plot - Apatris (tsss tapes, 2022)

Aris Giatas, Vasilis Liolios, and Yiannis Tsirikoglou perform collective compositions for tapes, piano, percussion, and electronics on the four-track, 23’ Apatris.

The piano a disjointed melody’s nervous stumbling, the curt plink of muted keys and the glowing decay ringing out in tremulous cadences. The first part might pluck the strings inside and strike the body to resonate abyssally hollow. The environment surrounding the piano in each part is distinct from the others. The frictional flicker of turning tape and the glitch of its rearranging grains with electric whirr and whomp. Unobtrusive yet ubiquitous white noise with ululating oscillations. A symphony of chitinous shaking and rotational snare play with singing sines. Turntablesque scratching and rip and chirp of rewinding with a turning chugging. A moment of respite in each part, the environment drops out, only to return and appear more oppressive after its absence. But the piano perseveres, changing little. A kind of refugee tossed among these harsh states.

- Keith Prosk

Forbes Graham - Solo Horn (Sound Holes, 2022)

Forbes Graham performs two quarter-hour tracks for trumpet and objects on Solo Horn.

“Grey Etchings” seems to explore ambiguities in the sounds of trumpet and other objects. Glimpses of recognizable trumpet tone and something recognized as not trumpet and acousmatic moments where the two blur. Key clicks like unsealed jar top pops phase into something too quick or something too wobbly to be trumpet. The shear of breath becomes something rubbed, something scraped, could be anything as much as air through a mouthpiece. An alternating amplifier hum activates around the moments the trumpet is activated, groaning, sighing, wheezing, whistling. Something rattling in metal that could be in trumpet if it didn’t occur together with its bluster of squeegee and dolphin talk. The whirlpools and flurries in “White and Blue Etchings” are softened and dulled, mediated through water, which carries the irregular metronome of dripping water and the slow motion resonance of its tapped cistern. Again the horn here as just another object in a system of sounding objects. And in making the horn just another object, a thing unbound to the fealty of virtuosity, virtuosity seems silly, opening the heart to the wonders of the sounds themselves, expanding its language in more ways than texture alone.

- Keith Prosk

Sarah Hennies - Clock Dies (Earle Brown Music Foundation, 2022)

Talea Ensemble, conducted by James Baker, performs Sarah Hennies’ half-hour composition Clock Dies for flute, clarinet, violin, viola, cello, piano, and percussion.

A clockwork complexity made from simple means. Precise rhythmic sequences repeated ad nauseam after some time discard components and integrate inclusions to disorient time. Likewise swift transitions between distinct material baffles any linear flow. Harmony stays in the family, winds, strings, or bowed percussion and its long decay sustaining together, and when it seems to sour is when harmonic interactions bloom. Intermittently imitations of tremors over what must be fatiguing durations challenge performers’ coordination, twitching wrists, rapid tapped feet, small quick key clicks, maybe weird tonguing. There is a dark humor in seemingly nudging the ensemble to error, in recognizing some repetition as music and some repetition as task. The embodiment and not the ideal of the performer is always underscored. Moments of familiar harmony and trackable patterns alternately feel more comfortable in their sparsity and more unsettling for the same reason.

- Keith Prosk

Talea Ensemble on this recording is: Barry Crawford (flute); Matthew Gold (percussion); Stephen Gosling (piano); Chris Gross (cello); Marianne Gythfeldt (clarinet); Karen Kim (violin); Hannah Levinson (viola); and Alex Lipowski (percussion).

Catherine Lamb - aggregate forms (KAIROS, 2021)

JACK Quartet performs Catherine Lamb’s string quartet (two blooms) and divisio spiralis on the two-and-a-half hour aggregate forms.

Slow sustained strings sometimes silent for a moment but more often dynamically dropped out to return beating create a sense of suspended gradual expansion, most often appearing to move in pairs, two layers of distinct pulse, the structure perceived through these microstructures in two blooms. Perhaps because it is an earlier composition, I hear the Hindustani music in it, phylloidal layers of metallic corrugations like tanpura, bowing returns in raga rhythm, deep bass register oms.

Sustained strings in endless gliss approximate a curve in their progressing web of lines in divisio spiralis. Pauses between pieces and within pieces like light against cames, small discontinuities in something recognized as continuous. From piercing frequencies towards a swaddling harmonic warmth, beating becoming stronger, at times ethereally melodic, an ascending spiral curve.

- Keith Prosk

JACK Quartet on this recording is: Jay Campbell (cello); Christopher Otto (violin); John Pickford Richards (viola); Austin Wulliman (violin).

https://www.kairos-music.com/cds/0018010kai

Jack Langdon - Less Than You Remember (Sawyer Editions, 2022)

Jack Langdon performs three solo organ improvisations on the 47’ Less Than You Remember.

Emphatic staccato like young lungs through a new wood train whistle neuters the warm sustain expected of organ. Then at the threshold of continuity and sounding, its bellows close enough as if to fill the pipes but not close enough to vibrate them. But “Decline” slowly intersperses layers of chords to build towards the throb of warm sustain and a mellifluous melody. Dense droning chords whose undulations appear to alter autonomously begin “Old Path,” corporeal vibrations that accentuate the architecture of the instrument. And a twinkling and startling melody sprinkling it. Each begins by subverting characteristics of the organ; each ends having succumbed to them. Always an argument between high and low registers. Perhaps “The Highest Fall” finds an in-between space, its sequestered chords trailing beatings like a smoking aura, ending not in beauty but in sonic distortions, tones shaking in its low rumbling.

- Keith Prosk

Kasper T. Toeplitz - CoRoT-3 (Les Naines Brunes #3) (self-released, 2021)

Kasper T. Toeplitz presents the 36’ fixed audio arrangement - featuring Elena Kakaliagou on multitracked horn and effects - for CoRoT-3, a multimedia project whose performances include music and images from the composer, live horn from Kakaliagou, and choreography from Myriam Gourfink.

Any horn is unheard, so heavily distorted as to seem more amplified power line hum, deep strata of diverse pulse in seismic rumble and whirr. Morse distress amidst disintegrating wind. Waves expressionistic outlines of the endless expansion of perpetual combustion in slow motion. Some arcane orchestra breaching the maelstrom but it is still not horn-forward. True to the brown dwarfs it takes its inspiration from, the sound is massive and engulfing, physical in its volume.

- Keith Prosk

Tongue Depressor + Austin Larkin - Curve of the Spine (Obscure & Terrible, 2021)

Zach Rowden and Henry Birdsey - the duo Tongue Depressor - combine bass and cello with Austin Larkin’s violin.

Seeming to evolve directly out of previous Tongue Depressor recordings, especially the Fiddle Music series, Curve of the Spine finds the duo’s extended explorations of minor-feeling harmony-in-drone inflected, subtly but decisively, by the contributions of collaborator Austin Larkin. Certainly, the addition of another instrument, if nothing else, “deepens” the atmosphere, tilting further towards drone-as-enveloping-soundscape. But, aside from “several more vibrating strings,” what Larkin seems to bring to the table here is yet another conceptualization of ‘drone music,’ or set of tools from which drone (and what is it, really, that unites these ideas under one heading?) may be built - an emphasis on drone as constructed from overlapping cyclical “cells” of varying lengths and speeds, each instrument seeming to periodically find and stick to a new repeating fragment, a pluck or a slide or a note, and the overall soundscape comes across as corollary to those structural patterns’ non-metrical coincidences. The resulting music therefore strikes me as having a greater sense of “architecture” than prior Tongue Depressor recordings (which is not meant as a value judgment), perhaps aligning with the release webpage’s foregrounded assertion that “there was nothing to figure out, nothing to explore, the forms were in place.”

- Ellie Kerry

Michael Winter - Counterfeiting in Colonial Connecticut (XI Records, 2022)

Gemma Tripiana Muñoz, Elliot Simpson, Mandy Toderian, and Michael Winter present a 41’ performance of Winter’s Counterfeiting in Colonial Connecticut for guitar, high and low accompaniments, readings, and electronics.

A knotty outsider guitar melody, ringing harmonics, rambling circular similitudes based on the coin press and its imperfections with rippling bass guitar decay and glassy piccolo whine runs through Counterfeiting in Colonial Connecticut. In between readings of excerpts from Kenneth Scott’s titular book and perhaps other numismatic publications, the general remarks in the score, and a selection of texts related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, and the fractures - especially in US society - that these events lay bare, often but not always in threes like the instruments, the counterfeiting accounts central like guitar, flanked by other readings. The selected counterfeiting accounts are particularly punitive and cruel, cataloging arrest, capture, imprisonment, fines, the forfeiture of bonds in absence due to illness, denied petitions to imprisonment in an unheated cell in winter, lashes, dismemberment. Which echo in the country’s systems today as told through accounts of the pandemic and response to George Floyd’s murder. I have a suspicion that these and other small mimickries threading the music and the text and the two together conceal a clever sleight of hand but the recognition of injustice in the content for similar suspicions leverages my confidence to appreciate it at face value.

- Keith Prosk

Zinc & Copper - Éliane Radigue: Occam Delta X (self-released, 2022)

Robin Hayward, Hilary Jeffery, and Elena Kakaliagou present an hour-long performance of the Éliane Radigue composition for tuba, trombone, and horn, Occam Delta X.

Deep low tuba tones guttural, growling, in chanting repetitions and sputtering tonguings from horn and tanpura formants of throat singing trombone layer and extend and blend in long meditative duration to dissolve discrete soundings into ethereal waves of om spilling singing beatings. Overwhelming wonder from this ascetic practice. An audible union of the ensemble’s preoccupations with the protolinguistic aspects of brass and the composer’s Buddhist faith.

- Keith Prosk

Peter Conradin Zumthor - things are going down (Edition Wandelweiser, 2021)

One of my favourite things about Peter Conradin Zumthor’s things are going down is the large extent to which it lives up to the mental image that its title conjures, as well as to its curious credits: piano player and piano tuner. Zumthor starts the piece with a small, repetitive piano melody played quick enough to take on a pulsing effect. It could be mistaken for classic minimalism at first, where a simple repetition of octaves may gradually evolve or advance into a beautifully complex music, but Zumthor’s performance just stagnates and circles around its pulse. It feels committed, confident and purposeful as a war drum. It takes a few minutes of this provocative repetition for the effects of the loosening strings of the piano to be heard, for the listener to become aware that things are going down.

Through the 46-minute composition, René Waldhauser gradually detunes the piano, dampening the thundering war drum into an incoherent blob of dissonant reverberation by the ten minute mark and carrying on from there. Apparently the risk of snapped strings, the piano figuratively striking back against its abusers, was high enough that both players had to perform while wearing goggles. As the ugly sound-mass of loosened, shaking strings grows, it overpowers the striking keys, creating the illusion that the key-sounds are an effect of the dominating string-sounds and not the other way around.

As the lower strings loosen into unplayability, Zumthor updates his performance to focus on just the higher notes. The result is the re-appearance of the piano as an identifiable, comprehensible, attractive instrument. The upper strings are loosened enough that the keys still carry a considerably janky effect, but their shakiness actually results in surprisingly pleasant layering harmonies. It’s a beautiful moment of levity. It gives the impression that things are looking up, and, like before, it might even take the listener a moment to realize that things are still going down.

The upper strings descend back into the same archaic mess of abstraction, but now they bring along high-end metallic scrapings to give this detuned piano blackhole an even uglier voice than before. As the piano is forced into its lower limits it sounds increasingly mechanical – the incidental sounds of low-end thumps, awkward shakes and harmful scratching accompany each strike of a piano key, building into a mammoth echo which rings within the piano’s body while its organs are severed.

One of my other favourite things about the piece is that by the nature of its concept it promises a specific non-climax: the tipping point where the detuned piano can no longer be played, where the strings have stretched out of audibility and the piano is rendered mute. It does get there, but the tipping point is more dramatic than I anticipated, with Zumthor unloading a barrage of failed high notes, resulting in a gorgeous mess of descending string smashes, like a frail last hurrah as the instrument finally falls apart and loses its voice, completing its descent into uncomfortable industrial melancholy.

The composition does have a last trick up its sleeve, however. After the humiliating climax, the chords begin to tighten again. The scraping fades away and the piano regains its voice. For some reason, things are going up. I can’t help but see it as an optimistic ending – minutes ago it seemed all is lost, and now the pianist has returned and is playing with greater conviction than ever. One could read this as an analogy for a machine that naturally shuts off before turning back on by its own processes, but I’d rather read it as a beacon of hope that suggests that nothing can be so far gone that it can’t start going up again.

- Connor Kurtz

https://www.wandelweiser.de/_e-w-records/_ewr-catalogue/ewr2119.html

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate this newsletter and have the means, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the regular writers but the musicians and other contributors that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the regular writers, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of work it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians and other contributors $1.99 to $4.64 for December and $2.90 to $7.74 for January. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.