Thanks to Kevin Good’s Songs for Two I recently stumbled across B-Journal, a periodical for writing and visual art that might include scores or something like it among its volumes, organized by Cherlyn Hsing-Hsin Liu. It has been added to our resource roll.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate this newsletter and have the means, please consider donating to it. Your contributions support not only the regular writers but the musicians and other contributors that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the regular writers, and distributes 40% to musicians and other contributors (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised the newsletter of work it reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. The newsletter was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.00 for March (no donations received) and $2.27 to $6.06 for April. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Maximiliano Mas is a composer, performer, and improviser born and based in Buenos Aires and perhaps most associated with guitar and lute. Over video chat we talk about space, time, sound images, art, mimickry, synthesis, growth, and experimental music.

Recent releases include Sombra acústica with Mariano Balestena, Iván Consorte, and Catriel Nievas, Linde with Hernán Vives, La escena circular, and Lo que se esconde entre las notas. Maxi runs the label Rumiarec.

A Spanish-language translation of this conversation by Maxi is available on MUSEXPLAT, a network for experimental music from Latin America.

MM: Hi, Keith.

KP: Hey, good morning. Can you hear me?

MM: Yes. You can hear me too?

KP: Yes. How're you doing today?

MM: Fine, fine. I just left my little daughter with her grandparents so they can take care of her.

KP: Nice.

MM: Yes. Because I love to have her around here but she’s quite noisy, so to be more relaxed I prefer to leave her there.

KP: Yeah. Have y’all been relatively locked down the past couple of years too? So you’ve maybe had her in the house quite a bit, or more than you usually would.

MM: Yes. It was weird because she was one year and a half and she had already been to baby kindergarten, so she was really used to being with other kids. And when lockdown started it was, awesome I can be with my family all day, and after two months it was like, oh my god I have to be with my family all day. You live that too, no? You’ve been on a lockdown?

KP: Yeah, the states right now are kind of exiting out of it, I think, I don’t know. But I don’t have any kids yet, so I haven’t had to deal with at-home teaching or at-home care yet.

MM: OK, OK. Well, in a way I like it too. In a certain way I used that to get inside the music because during the lockdown I made a record, and it was here in my house. The whole time I was recording, I could hear my daughter running around, and my wife talking to her, and my cats. So I use it like, well it’s gonna be like this. I have to make a record here in my house. So I didn’t fight with those things. I let them get inside the music. And now everything that I’m making, if I’m going to make a home recording, I wait until they come back from school, from work and I start rec’ing when they are around so you can feel that because… I don’t know, I like it. When I’m listening to some music and I listen to her voice, it’s… because I think, when she is twenty and she listens to that it will be cool, oh I can hear my voice when I was a baby with my father’s music.

KP: Yeah, it’s like another form of a family photograph.

MM: Yeah.

KP: Which album are you referring to?

MM: It’s an album called La escena circular. There’s a moviemaker here from Argentina called Cardini, and he was like the first experimental filmmaker from the ‘70s here. And he has a short movie called that, and I took that name from it. And it’s the first album that I rec with my lute. The one that you listened to, called Lo que se esconde entre las notas, that I did with the electric guitar and the acoustic guitar, that one I went to a studio and I did it super clean. The other one I played this instrument [holds up lute].

KP: Nice, OK. Yeah I was gonna ask… I had seen some pictures floating around with you and something else and I was gonna ask if you also played lute or rebec or something.

MM: Yes, it’s a lute. It’s a Renaissance lute, basically. But in the Baroque era, about two hundred and fifty years ago in Italy, they started adding basses so they could use it with the singers. So at the beginning the instrument was with only these seven strings and it’s like a regular lute, yes. But they start adding the [plucks low register strings].

KP: Yeah, it’s got like a whole other peg board.

MM: Yes but this was.. the basses they are only open strings, you can’t push a note. So what I do with this, I use the bow of a violin and basically I make a lot of things with the bow, like noises like this [plays buzzing low tone]. Now it’s like my living instrument, I use it all the time. And the music that I’m making now, I’m recording a new album with this and the groups that I’m playing are using this too. I like it.

KP: Nice, perfect. Going back a bit to the lockdown, pandemic bit I did notice between the records that you’ve got going on and your SoundCloud activity that it seems like things have picked up in the past year or so. Is the catalyst for that being locked down, or is there something else?

MM: Yes, yes, because since I’ve been here in lockdown I started making an album with Hernán Vives. I study improvisation with him and he also plays these kinds of instruments. He plays Baroque and Renaissance music but he also plays contemporary music and that kind of stuff. And during the lockdown we started coworking because we started making meetings every Sunday and we called for different artists and friends that we know. We made zoom meetings for two or three hours and we started sharing the music and the art things that we’ve been making. So we started a really close relationship with Hernán and ended up making an album together called Linde. And after that we say, OK now we have to look for a label to publish the album. And I started sending mails to different labels and we started talking, well if nobody wants to publish it we can do it ourselves. And that was his idea at the beginning. And that reminds me, when I was young, I started music at seventeen, playing like punk rock music. And it was really common that you release an album and you put a name for a label that didn’t exist. So you say, OK this was on the Satan Claus label. But after two or three records you can say that you have a label and it was really common that a friend says, hey can I put my record on Satan Claus label. Yeah, right. So we start modelling that idea to create a label of our own. And that’s Rumiarec. So we call up our friends, hey you have an album that you want to publish. Yeah, right, OK, send it. So we start doing that. After awhile, after these first four records that we have on the label, I was all the time looking for places that can make a review of the record, like you do. So I start sending mails to people that I know, and it was really hard. And I saw on Instagram, the people from MUSEXPLAT - that means Latin American experimental music - that they were looking for people to collaborate, so I sent them a message and they say, yeah sure we want you to give us a hand because there’s nobody in Argentina collaborating with us…

KP: Isn’t Hernán part of it as well?

MM: No no no no, it’s just me. So I send them a mail and they told me, OK send us an interview that you make to anyone you know and you have to send at least one interview per month or a review. So I was like, sure I can send you ten… ‘cause I know a lot of people. All my friends are musicians. All of them would be more than glad to have an interview or a review. So that was how it started because we had a meeting where they introduced me to the staff, of MUSEXPLAT, and they told me, well what do you want from this? I told them, OK I want you to make reviews of the records on my label, oh sure yeah of course we’d be more than glad. It was a win-win.

KP: Yeah, yeah, that’s very cool. Going back just a bit to the story of Rumiarec. Your motivations were to self-release and it just grew from there or was it a larger thing, wanting to advocate for your friends and your local group on a larger level?

MM: It’s a little bit of both, you know. Basically… Hernán is older than me, he’s like fifty-three, I’m thirty-seven. He has a really large career because he started his career in experimental music and Baroque music when he was about twenty years old so when I was really really really young he was already on the scene of the music. So for me it’s like a way to make my way in the music world and for him it’s like… I don’t know, we should ask him. When we talk about this he has an idea like - I really like it - he thinks about Rumiarec like a tree, and every record is like a leaf. So after ten years, this is gonna be really great. And at the beginning if you start looking day by day, it’s gonna be really hard and really boring. But if you look at it with some distance it’s gonna be really great. And he’s right because we started with Rumia in July of last year and we have four records, we sold a few, we have some reviews, we met new people. If i have to make a balance, it’s positive, it’s really good.

KP: Yeah, I think it’s badass. You mentioned MUSEXPLAT as well. I’ve kind of been looking through it recently and I did see that it’s kind of reviews, interviews… is it also a social network in way?

MM: Yes, yes. It’s really crazy because when I had that staff meeting there were like twenty guys and girls there and they all know each other but they were from Mexico, Panama, Venezuela, Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, and me from Argentina, and I think there was a girl from Ecuador. And I said like, fuck it’s like really huge. Because there are guys from Mexico about… I think they are no older than 30, and they built all this in three years and it really works. There’s only one leader, Emi[lia Bahamonde Noriega], she’s like the general, I don’t know how to say it. And she’s there all the time. She loves this project. She told us that you have to tell the people to subscribe to this, because it’s like a social network. You can like a friend of a friend here and you can send messages, you can subscribe and they send you the last review that everybody makes, they make workshops. Like in the last days of January they did the WASI FEST, and there were people from all of Latin America sending videos of their music and workshops - we gave the workshops, for example I did one of writing on experimental music. There were a lot of workshops. And it was really good.

KP: And what it’s trying to do… is it trying to advocate for Latin American music between Latin American nations or expand as outward as possible as well?

MM: They are trying to expand it all the time. All the time trying to find new people to start coworking and there’s a part on the website that when you subscribe you can put where you are from and there’s a map where you can see where all the collaborating people are located in the world. Because it’s for Latin American music but there’s a lot of Latin American musicians in Europe, the United States. It’s nice.

KP: Nice. I feel like I picked up on quite a few different kinds of music too. A little left field but dance music and also experimental… or, not to say that dance music can’t be experimental but closer to what you’re doing. Is there something that ties the group together other than geography, as far as musical throughlines, commonalities?

MM: I don’t know. Because what do we think is experimental music? It’s like, why can you say something is or is not experimental? I have a personal idea but I started checking the site and the canon that they put for something to be experimental or not, it’s really huge or it’s really flexible. Because if you ask me, OK Max what is experimental music to you, I cannot put it in words maybe but I can say, OK Sergio Merce is experimental music. I think that is experimental music. Because there’s no sense of any other music, it’s really experimental. If you can say, oh this sounds like this, this sounds like rock, this sounds like that, it’s weird music but they have a lot of essence of different kinds of music, it’s experimental music but it’s like… I don’t know how to say it… it’s difficult for me to say it in english because I don’t have the words… but if you try to say it accurately, what is experimental music, it’s not that easy. You can commit a really huge mistake. I thought that experimental music, it’s only the music that didn’t have any kind of reminiscence… when you listen to something and it’s like, oh this is blues, this kind of sound is Pink Floyd, they remind you of certain music. There’s a kind of standard, you can say this is from this kind of music, this is from there. When you listen to a record of experimental music and say, this is a blues thing, this is a Pink Floyd thing, this sounds like Jimmy Page, Hendrix… at the beginning I thought that that can’t be experimental music. Because it’s like a collage, a puzzle. But on MUSEXPLAT, they agree with that. They say, no no no that is experimental music too. Experimental music is just not regular music so it can be dance music, it can be post rock music, it can be weird tango music, it doesn't have to be European minimalism to be experimental music.

KP: So MUSEXPLAT is dedicated to experimental, whatever it calls that?

MM: Yes, but they have a really flexible way to say, this is experimental music. The other day I was writing a review of a friend’s record that is really really good but it’s like you can listen to Floyd music, Frank Zappa music on the record. It’s not like this pure experimental music. It has a lot of reminiscences of rock, jazz. I wrote the review and I told my friend, let me ask if they want to put it on MUSEXPLAT because I don’t know if they will consider this experimental music or not. And I sent it to Emi, the girl that coordinates all the activities, and she’s like, yes this is really good, yes you can put the review on MUSEXPLAT. OK, good. So I was happy for that.

KP: Nice. Yeah, experimental music, I… I try to stay away from the word unless other people are using it, just because the meaning can be so fluid. But yeah I guess it did seem maybe a little wider than my conception of it on the site. Just because you mentioned it, would you be willing to narrow down what you view as experimental music a little bit? [laughs]

MM: [laughs] Yes. What it is for me, what I think is experimental music… what I’m gonna say is how I do experimental music. I don’t want to say what is experimental or not because I don’t want anybody to crucify me, you know. For me experimental music, it’s like it’s a game of words. Instead of saying experimental music I say experiment with music. So what I do is find something that I want to experiment with. For example, the record you reviewed, it’s a gameplay of the harmonics. You know James Tenney?

KP: mmhmm

MM: Well I took the Koan piece for violin, basically it’s a really long glissando. So he put a note and then the same note so he started to make a gliss. So that record, Lo que se esconde entre las notas, the first piece, it’s like my version of Koan. I start making a melody with some harmonics and I start making the gliss with the tuning and start playing in the meaning of it like a game, no. How that note starts going down and making new harmonies with the other harmonics that keep ringing. And that was the idea. Playing with how a harmony can change because one note is moving. On the new album that I’m making with the lute, I’m making a tribute for a different composer, an Argentinian composer called Gerardo Gandini.

KP: Hmm, I’m not familiar with him.

MM: He already died. He’s really famous. Do you know Piazzolla, Astor Piazzolla?

KP: Yeah

MM: He plays the piano with Piazzolla. He is, in Argentina, after Alberto Ginastera, the biggest contemporary music composer, so he’s… wow. He has a piece that is called Eusebius, it’s a nocturno, it’s four nocturnos for one piano or one nocturno for four pianos. So basically it’s a piece that you can play it one by one or you can play it with other guys all at the same time. And actually the music sounds when you play it with the four pianos. But if you want you can do it alone one by one. He took the music from Schumann, the Carnaval, and he started taking out, well I’ll use this note and this note and this note for the first part of the piano, for piano two this this this, and he made a collage like that. And when you play it all at the same time, you can feel the Carnaval of Schumann in a contemporary way, it’s not exactly right. So I made that with the lute, just took the idea. I made three pieces for the lute that when you play it all together it’s like, wow that’s the piece. And the experimental part, it’s that every piece I record seven different lutes, OK. I put my recorder, I have a TASCAM that has two microphones so you have the pan, you can start panning the sound. So I put it in the middle of my living room and I start playing, I stand up, and I start moving, and I play all the crescendos and the diminuendos by approaching or getting away from the microphone. I make the mix in real time. When I play I make the mix. So the first track, it’s seven lutes, six minutes, six minutes, six minutes. I put them all together on the DAW and I just press play, I don’t touch anything about the volumes or the panning. You can also listen when I press play or in the record press stop, you can listen to my neighbors dog yelling, so when you listen to the pieces it’s like you can start feeling all the lutes moving and that’s my way of experimenting. This is my new experiment, make a real time mix. It’s also a way to play… I take Philip Guston… do you know him, the painter?

KP: mmhmm

MM: I take four paintings of Philip Guston from his abstract period. One is called Attar, one is called Painting. And I took those paintings to make the music score. I think I have one here to show you what I mean… so basically they are like doodles. Those paintings they are like these forms, really weird forms. With space. They are white on the back and these forms are pink and red in the middle, and they have different shapes. So the idea was to try to recreate those paintings with sound and mix that with the idea of Gandini’s Eusebius. So basically what I did is put one painting and then I put the other painting on top, on top, on top. And that is like a really red glob thing and that’s basically the last track of the album where you can listen to all the pieces together. It’s not already… I sent the tracks to a guy to clean them up of the space noise and that kind of thing… he does the mastering. I am really happy with this one because… I don’t know. I feel that it’s like… it’s warm. Because when you’re listening to it, you can listen to the wood of the instrument, and you can feel the space. Because when I went to different studios what happens to me I feel like the music it’s not… it doesn’t have the space, it’s weird. It’s not three-dimensional, it’s two-dimensional. And it’s like it’s not real. We are all the time listening to something that’s not real. You go to a concert hall, it’s three-dimensional music. You have someone that’s singing or playing any instrument, you can feel the space. Maybe there’s people that don’t care but if you want you can start listening to the sounds that are going to the wall and have come back, or you can start paying attention to that. And it’s weird because when you listen to recorded music it’s like, fuck, it’s like the Egyptians. We are like this all the time [strikes a “Walk Like an Egyptian” pose]. We have really advanced technology to do these kinds of things but we are pushing really hard not to do it. You take the guitar, you rec, you put in on the console, and then let’s put some reverb, let’s put some chamber effect, let’s put some spacing effect and it’s like, guy why don’t you go to a fucking church and rec there, it’s going to be much easier, no? I don’t know if it’s gonna be easier but it’s gonna be more realistic. We push all the time to do something that is not realistic. I started noticing that when I started getting involved with early music. Because my wife, she plays early music, that’s why I play this instrument. When we started dating, she used to come to my apartment with a theorbo or with a Baroque guitar and so I started improvising with those instruments. Later on I bought my lute, right. But every time I went to a masterclass of early music, they talk a lot about if you play with the nails or without the nails, it was something really important for them. I used to play classical guitar so we use the fingernails, long nails to play that guitar. And on the lute, the strings are double strings, like on the 12-string guitar, so they don’t use the fingernails, they use the finger. And I remember one guy, he was giving the class and he said, the concept of the sound is a social construction and social constructions change all the time. I think that if someone played the lute in the same way that they played in the baroque time, we would consider that to sound really fucking awful because the time changed, the material that they used to make the strings changed, the idea of what is beautiful or not changed, everything changed. And you can’t rec a lute in a studio because it doesn’t sound like that. He was really provocative, he was trying to push us a little bit, and I think that I started listening to records in a different way when I listened to that. And I started to listen to a lot of albums that were recorded in a real church. In the beginning I said, this is fucking awful, I can’t listen to this. And with time and practice, I started listening to something else behind the notes, no. I started paying more attention to the place that sounds on the record instead of the song that they were playing, right. And it’s like I don’t know now when I play if I pay more attention to how the place sounds than what I’m gonna play. It’s like, oh this place sounds really good, I’m gonna play like shit but this place sounds really good. I worry about that. I like to think about that.

KP: Yeah it’s interesting that you mention the two-dimensional aspect. I feel like something I hear quite a bit around this kind of music is the concept of a sound image, or the recording is like a photograph, particularly with the music really dependent upon people hearing those harmonic interactions. What you perceive or what you capture really changes based on not just whether the players change their relation in the space, or the microphone changes their relation in the space, but whether there’s a humidity drop, or a temperature drop. So I feel like in those kinds of recordings you definitely get something like a crosssection of a whole or a still of something moving. It’s interesting too that you mention James Tenney because I feel like - going back to the experimental music bit - he had a super… I don’t wanna put words in his mouth, but it seems like he had a super specific approach of what he thought might be experimental music and it was kind of in line with a scientific approach, of trying things out. To redirect a little, you mentioned that you started out playing punk rock, and I noticed that there are some tracks on your SoundCloud like TOP MODEL and CAMPANAS that maybe are a little more on the rock side so I guess what brought you to this kind of music, what are some touchstones along your path?

Mm: [laughs] First of all, I’m gonna say something. That SoundCloud, I only use it… I study with Julián Galay, I started composition with him in 2019 and he’s living in Germany, in Berlin since 2020 so all our classes are virtual classes, so to show him what I’m doing, my work in progress of every week, I use the SoundCloud. Every time you go to SoundCloud - we have our meetings on Fridays - if you go there every Saturday it’s really probable that you can listen to the last thing that I did. I never promote my SoundCloud because I just use it for that, so it’s really funny you went there. On that SoundCloud, all the music you can find there, like TOP MODEL, I used to have a band, a rock band, we split in 2013, and it was a really good band and at that moment I was really influenced by rock, like Luis Alberto Spinetta and Daniel Melingo from here in Argentina and tango too. So how I got to playing this music that I am playing now… it’s like a really long journey but making it short I studied guitar with a guy called Omar Cyrulnik from 2010 to 2015, -14 and he played a lot of contemporary music. At the beginning when I started playing guitar I really hated contemporary music because I thought it was too snobby or something like that. But I really liked how it was written, you know. I started seeing all those doodles, like lines, arrows. I was like, that is super cool. And I started getting involved with that. In 2015 he went to Italy because he started working there and I was in Europe too on vacation and my wife starts talking a lot about this lute professor that - it was Hernán Vives - and it was like a month and a half only talking about baroque music baroque music baroque music. So when we came back Hernán invited her to his house in the countryside and I went there with her and he told me - he didn’t know me - and he says, tomorrow I play, I don’t know, a pub. And I said, well I’m gonna go. Because I thought he was gonna play like Bach on the lute but when I went there he takes out a classical guitar and he put clips, paper clips, metal on the strings and he started playing like that and I said, this guy has something special, I like this guy. And then he pulled out a lute, this same kind that I have, and he started making noises with the lute and I said, this is like punk rock music with early instruments with contemporary music. He was perfect. All the things that I love in music in a really synthetic way. I remember that the guy who makes his lute - I knew him because he is a friend of my wife - he was there at that concert and I told him, hey start preparing one for me because I want one. And he made my lute. It’s the same that Hernán has. It’s really cool. The same day, when I arrived home I took my cell and sent a message to Hernán via facebook and was like, I don’t know what I want to do with you but I really feel something so I wanna go to your house and, I don’t know, do something. And I went to his house and he takes out the guitar and he starts playing like a mad [blargh blargh sounds] and I was with my guitar, frozen and he stopped playing, he looked at me, and he said, do I need to say something, you’re gonna play or what. I said, OK [blargh blargh sounds] we start playing free improvisation and it was really good and we did that for one year. It was really good.

KP: Nice. You studied improvisation with him and then you’re studying composition with Julián?

MM: Yes. I don’t go to any institution at the moment. It’s like I feel more comfortable studying with people. I can use the time better in that way.

KP: Yeah. And you mentioned at one point you were influenced by tango. So when I think of Argentinian music, I feel like there’s a very strong association with the guitar - though it might seem like you’re moving a little more towards lute - but with the music you’re making now, is there a connection with the history of the music that’s there, whether that’s on the classical side like Piazzola or something like tango or milonga?

MM: No. I don’t think so. No. Not at all. Because tango music, it’s a rhythm, you know. It’s not about the melody, it’s about the rhythm and the color of the instrument because you can be playing any kind of music but if you’re using a bandoneon it’s gonna sound like tango or if you do the rhythm then it’s gonna sound like tango too. It’s like if you’re gonna make something using that material, in my way of seeing things you have to jump into that swimming pool and go really really really deep. Because if you are only going to do the rhythm, it’s like what the fuck are you trying to do. There’s a really good composer called Roland Dyens, do you know him?

KP: mmmm

MM: He died a few years ago, he was French, he writes a lot of music for guitar and he was like [explosion exhalation] really good. And he used to do that kind of thing. OK, Tango en skai, it’s like tango but full of common places, OK, or bossa, whatever, and full of [mouths rhythm] and I think that kind of use of the materials, it’s plastic, you know, it’s not real. I can’t do that kind of stuff. He did it because he’s really great and if you listen to his music it’s gonna blow your mind but I’m not Roland Dyens and if I try to do that it’s gonna be a mimic of something. It’s gonna be really plastic. I prefer not to do any reference of that. Actually, now that you mention it, I was rec’ing the other day and there was one moment that I was playing with the bow and I was doing something like [mouths beat] and one moment [tango beat] and I was like no. A red light saying no no no no no. And at that moment I changed it because I didn’t want to have any reference of that.

KP: Yeah, I’m almost imagining a harmonic music and you’re somehow able to sync the beatings to where they’re in a tango beat or something [laughs] So I guess getting a little more into what you personally do, I feel like we’ve kind of danced around it a bit, but if I had some snapshots of what I’m picking up on in what you do, I definitely hear the environmental sounds peak through occasionally. I feel like it’s generally relaxed but not afraid of speed. Kind of soft but not afraid of volume or dense clusters. Definitely enjoy melodies. But I feel the biggest thing I’m drawn to is that some of your stuff has super pronounced silences and then on the other side sustained sounding where that harmonic stuff comes from whether it is beatings or a kind of tanpura sound like on Linde or Maine. But what would you say are some ideas or approaches that you find yourself returning to lately?

MM: It’s like I have two main works. One about the lute, more like going to noise music but not noise music using a pedal, trying to be gentle. And there’s the other work with electric guitar that’s even more clean. So when I work with the lute I work with the space and the noises of the environment and the noise that I can make with the lute. And when I go with the electric guitar I play with the harmonics. I’m writing a new piece for the guitar like going deeper on Koan - remember that I told you that the album of electric guitar was like James Tenney’s Koan - I go deep with that using the loop and ebow and the slide. So what I did, I rec a C-note, pure, with the lute for about ten seconds with the slide and then I press overdub and I leave the overdub running all the time so it’s all the time rec’ing and playing what I’m rec’ing and it’s making the accumulation of sounds. The piece lasts ten minutes, so in those ten minutes basically it’s going from the C to the D and that’s it. It’s a really really really slow glissando. So the loop station, it’s rec’ing and playing those micro- uber- microtones and starts making a beat [mouths beat] and that starts growing. So basically when I play the guitar it’s about the glissando and harmonics. And when I play the lute it’s about the space and the noise. Just being like really accurate. All the time I am working like this [climbing steps with hands] but I know they are separate because all the things that I play on the lute are… I don’t play live with the lute. I play here, rec’ing for example. If they call me tomorrow and say, OK there’s a gig you wanna go, I go with the guitar because I can plug it and I can put really high volume. With the lute I go if it’s a really small gig, like five people, and I can play it quietly. Because it’s an acoustic instrument and every time that I try to plug a microphone… I put two different microphones on the lute, but it’s not the same because this instrument has really really really good reverb sound because all the strings that you can press they play the role of the harp on the piano, you know, if you leave the pedal open and you play a note, you can hear all the notes ringing [taps the lute to resonate like a piano] so if there’s ten people breathing and opening a candy it’s like I can’t play. It’s not gonna be heard. And when I use the microphones, I use these kinds of microphones that I make myself that you can stick to the lute. Basically I put one on the body and one on the neck and I make a mix on a little mixer and I did that for a while and after awhile I decided I wanted just acoustic, not with the mics.

KP: Yeah. I don’t wanna go against what you’re saying but it seems like they’re not so separate, that there is a little bit of each in each other. Like on the lute you actually are paying attention to harmonics quite a bit and on the electric guitar, harmonics being so space dependent, you’re really paying attention to space too.

MM: [laughs] yeah, totally, totally. It’s like I can’t stop being me, I can’t split myself OK so it’s all the time like this. But I’m trying to not make like this [overlapping hands] I like the idea of having two different trees that are growing. Actually now on the lute what I do on these strings that you can press is tune them in Just Intonation and I play with the bow and when you start pressing with the bow they… you know about this, you’re a musician right?

KP: I’m not.

MM: The tuning of the strings it’s like a scale, it’s a regular scale OK. From E to F. When I tune them with Just Intonation it’s not like the regular intonation, the notes are not 440 for example for the A, it’s 443, 442, something like it… I do it with the phone. When you play with the bow on that cluster, a new note rings that is not a note that is tuned there. So you can feel the seven notes of the cluster plus the note that comes out as a result of all the harmonics that are playing on the other strings. So yes I work a lot with the harmonics here on the lute.

KP: Nice. I guess are there… do you think about silence a lot in your music?

MM: Yes. On this new record, yes. Because I told you that I go for seven tracks so if I play a lot on each the result is gonna be like [blob sounds] so when I start rec’ing I put the phone with the clock and it’s like, OK I have to wait one minute, OK I stay still or I walk really silently. I start making those silences because I consider the time like a space for this album. I told you that I used the paintings of Philip Guston and I started thinking of time as the space. It’s crazy because I use the time like a space that I have to walk through, not something that is coming. When I play classical music or contemporary music, I used to use counting on headphones because it’s weird, it’s hard, you’re playing with electronics, so you have to be counting or you can put the count on a different track. And all the time when I play that, the feeling that I have it’s like I’m sitting still with the instrument and the time was coming towards me. It’s not like I was moving through time it was the other way. I was still and the time was going through me. And with this new material that I am doing I have the opposite feeling. It’s like the time is there and I am walking through time. Because when you have this huge silence, like one minute of silence, it’s not coming, you are going. You are going to the next sound, so it’s something that you are walking through all the time. It’s a really nice feeling for me.

KP: That’s super interesting. Do you think that comes from - with the contemporary music with the counter - that it’s almost more of a task thing whereas what you’re doing when you’re walking through time you’re in the moment listening and creating?

MM: No, no because our brains, it’s super cool, we can do a lot of multitasking but our perception is not that multitasking. For example now I’m thinking that I have to do this, that but I’m paying attention to what you’re saying so I’m not paying attention to the motorbike that just passed. I listen to it but I’m not putting my heart in that. For example if I wasn’t paying attention to you I could say that bike was a small motorbike or the wheels were not that huge for example [listens] that one was bigger than the other one, because I was paying attention to that one. When I was playing that kind of contemporary music with the counter with electronics and with the guitar it was like I can’t be paying attention to this and to the electronics, my fingers on this hand, my fingers on this hand, and producing like a really good art material or sound quality. I think it was more like, survive through this. It’s like, it’s making music or it’s playing music, because it’s not the same thing you know. I was playing music, I wasn’t making music in that moment. It’s really different. Because you can, I don’t know, make a mistake on a note, whatever, but you are making music, you are putting all of your being there. When you are playing music, you are putting your fingers, you are putting something else, and maybe you don’t miss any note but it’s like you don’t move something inside anyone. It’s like this guy that taught me how to play the guitar, he all the time made the - because he was a really badass guy - he says all the time that, in english the words for playing music in the way of making it of rules it’s more clear, you are playing. So the way that a kid is playing. In spanish we have different words for that. When we say that a kid is playing with his toys we say he is jugarndo but when you play an instrument we say he is tocarndo so they are two different words and each word has different meaning. He all the time said stop touching - tocarndo is to touch - stop touching the instrument, start playing the music, start playing with the music, start making music. So that was something interesting. And the other thing he always said is that emotion in english, you can start playing with the word until you say motion, to move something, so you have to move something. Emotion in spanish is emoción, it doesn’t have any relation with the word of movement. So he said to make some emotion you have to move something and to move something you have to start playing with that something. So to produce an emotion with the music you have to start playing with the music, move the sound, play with the sound. This kind of play, wordplay was really inspiring. When I studied with him I didn’t understand that. I understand those things now. He has a lot to do with Pauline Oliveros. Do you know her?

KP: Of course.

MM: Every summer he made like a retirement to the countryside and we would play music - we went with a guitar to a place - we used to be like ten, thirteen, twenty guys. We did like tai chi. It’s one week that you don’t have computer, you don’t have a cell phone. You have to wake up in the moring, do tai chi. Then you have chamber music. Then you have guitar class. Then you have chamber music. Then you have tai chi. Then you have dinner. Then you go to sleep. For a week. Those retirements changed my life in a way of saying. And when I was in lockdown, I bought a book of Pauline Oliveros called Deep Listening, and I was reading through it and it’s like, wow man that’s like what we did in those places. And I sent him a message and I said, gee Omar I have a book that I want to give you, do you know Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening. And he was like, no. And I was like, fuck you’re doing exactly the same. And he was like, OK send me the book I will read it. I never sent him the book, but he didn’t need it. So it’s like I’m all the time coexisting with my different Maxis, with the punk rock, the rock, Deep Listening, classical, contemporary, experimental. It’s like different guys that coexist.

KP: Yeah, yeah. Would you say that maybe what you’re interested in now lately too is smaller, with a fewer number of people, like solos, duos instead of large ensemble maybe to help with that listening?

MM: Yes. I’m listening to a lot of solo music and I laugh because I wrote a piece that’s for a guitar ensemble, for seven guitars, but the way I wrote it down it’s like it’s one huge guitar. Seven guys but they end up being one guitar. For example there’s a part that’s like polyphonic counterpoint. So I wrote it and then to make it more easy to play it every guy plays only one string. It’s like a huge guitar but played by seven guys. That kind of stuff. I think that it’s because all the music that I make, that I compose, I have to be able to play it, even if it’s for an ensemble. So I am doing like solo music but for seven guys. And I wrote down another piece for ensemble and it was really hard, I worked a lot on that piece, it’s for cello, a drum, a flute, a saxophone, two acoustic guitars, and me with the lute. I was struggling a lot with, what can they play. I start thinking about different harmonies, different kinds of stuff. Later on I started making doodles of the music and, OK I don’t want to struggle with the notes, they are all gonna play the same note, and that’s it. So the music is only one note, we are all playing the same note. And I say, OK how is this gonna be interesting if they are all playing the same note. So I start making the idea of a universe and how the planets move around the universe. The sun, it’s the microphone so we are all planets that move in different directions around the microphone and it’s all again working with the space.

KP: [laughs] space in two senses

MM: Si si si si si. This is a work for Rumia because with Hernán we decided to make a disc that’s gonna be a collaboration with different composers and we made this ensemble and this is my collaboration for the ensemble. It’s gonna be, I don’t know, we didn’t even start rec’ing so I don’t know when it’s gonna be out. But I want to show you one of the drawings [holds up drawing of instrumental orbits] the cello and the drum are gonna be steady and then we all move around them.

KP: That’s awesome.

MM: Si. I hope this works, I don’t know. It’s again me playing with space, I think that is my - going back to when you asked what is experimental for me - I think that the space is the way to make experimental music for me.

KP: Yeah like you were saying earlier with the hieroglyphics, space is so often neglected in popular music… it’s almost like it’s in relation to popular music, like because it’s neglected there to experiment is to play with space.

MM: Yeah, yeah. And it’s funny because now you have microphones that are really cheap that are three-dimensional that you put on the floor and you start playing and it’s gonna be like, wow. But I think it’s like what I said before, it’s something cultural. If you rec an album for like a punk rock band that is about the space, I don’t think that people are gonna like it. I think people need to have the one guitar here, the bass here, the drum in the middle. It’s like I really like the Rolling Stones and I really like Prince, I really like them at the level that I listen to them like every day when I go to work and I’m on the bike. And I think if you put that on, if the guitar is like, I don’t know, five meters away it’s not gonna be the same. But it’s something that we make in that way and we are the ones that can change it. It’s like a construction. When Elvis Presley or even The Beatles made their first album, they were all playing together in the same place and there was one microphone in the middle and they were all playing. That is working with space. Then with time we end up putting the microphone on one guitar, so it was like it was on purpose, that they tried to sound like that. It wasn’t like, OK we couldn’t do it better. Actually they tried to do it like that but I don’t know if the people that came after them tried to do it like that because they have a sound idea, an artistic idea like, OK they do it like that so we have to do it like that, you know what I mean. They didn’t take the responsibility of doing something genuine. They tried to emulate the sound. When I rec’d that album that you hear on SoundCloud, the TOP MODEL track, it was the first time that I worked with a music producer and for me it was like, why in the fucking hell do we have to do all the time… he said, OK the two guitars are playing the same thing, one of you has to change. You’re making one chorus with the voice, let’s make three. Let’s put another keyboard here. And the feeling that I had - I really love the guy and I really learned a lot - but the feeling that I had when I talked with the other members of the band was that the texture of the… if you think of it like a painting, all of the painting is full of something, you don’t have even one moment to say [breathes] and it’s all here [hands on forehead] and I think I can’t do that kind of music. It’s not something that I enjoy. I don’t enjoy making it, I enjoy listening to it. The Rolling Stones do that. Prince does that. But I always have the idea that you should be able to play what you write, OK. It’s something that I overwrite when I make the lute play seven times, right, but the idea that you can do something really fancy and then go with the band and try to play… you make a lot of fireworks in the studio and then you go to the stage with the band and you can’t do that because you don’t have enough members. You can’t put a trumpet there because you don’t have a trumpet in real life so why did you put a trumpet on the record. I know that sax sounds really good OK but there’s not gonna be anyone on stage playing the sax so why do I have to put a sax there, huh. Well it’s something that I always think about. You have to do something that’s genuine, you don’t have to lie. It’s like art. The art, it’s something you can like or not but it’s not artificial, it’s genuine art, it’s not the same thing for me.

KP: Kind of going back to playing with space a bit, when you incorporate environmental sounds like birds or your daughter playing around the house is that consciously playing with the space?

MM: Yeah, of course. But it’s not that I have a track that has those sounds, they are there.

KP: Yeah, yeah, just like the sax you’re not gonna go and add some birds to a track.

MM: Yeah, yeah. I saw a video when I was younger and it was John Cage and I think he was in an apartment and he was playing the piano with the window open and a car crossed the street, something like that, and he says, you realize I can’t play this piece again ever right. And at the moment I thought that, well this guy is really eccentric. I knew him because I read about 4’33” and it was like, OK this guy is not a musician, it’s something else. But later on I was like, of course you can’t play this again because it’s not the same. If you think about us like painters it’s not the same. You can’t duplicate the color you make if you are making the colors. If you are making the pink, mixing the red and the white, it’s not possible that you arrive at the same pink tomorrow. You have to enjoy the pink that you have today. Because if you’re struggling with doing the same pink, you’re gonna be there for awhile because it’s not possible, sorry baby, it doesn’t work like that. You are working with a material, OK. With music sometimes we forget about that because we play the C and we play the C and we play the C and it’s always the C and we forget about how this C is connected with the place where you are playing it. And when you add the recorder it’s like, OK you are taking a snapshot of that C moving on the space. I think it’s magical, no. So I start rec’ing all the time, everything. Everywhere I go, I go with my recorder. I laugh because last winter we went to Iguazu Falls here in Argentina and I was with the recorder and we went on the tour - it was twenty guys - and I was talking with the guide and said, is there any way you can make them hold there for five minutes so I can rec this without their voices. And I ran like twenty meters and started rec’ing. And she was really really happy. My wife told me later she said he’s making the recording of how the water is falling here. And now it’s a part of my life. Everywhere I go I go with a rec. And I try to put the environment like a snapshot. In the summer I was in Bariloche, it’s in the mountains. And I was staying with my family close to a little river and my friend Catriel Nievas, do you know him?

KP: Yeah

MM: He stayed with us for two days there and I said before he left Buenos Aires - we had already been there - I told him, hey bring a recorder and let’s make an experimental duet of recorders. And he said, oh no no I borrowed mine to a friend so I’m coming just with a harmonica. OK, bring the harmonica. And my wife, she went with her theorbo because she has a concert that she’s studying all the time. So when Catriel arrives to Bariloche I say, OK let’s go to the - it was late at night - let’s go to the river and let’s rec. And he told me, well what are you goin to play, and I show him the theorbo and he was like, oh fuck yeah let’s do it. So we rec there, we do an improvisation and all the time we interact with the river. So it was like us playing, throwing stones to the river, playing with the stones, smashing stones, that kind of playing with the environment. It’s like everywhere I go I go with a recorder and rec things. I understand later on what John Cage said, right. And I use the recorder like if it was a snapshot all the time. My wife is taking photos, I am recording.

KP: Nice. That’s what I had lined up but did you want to go any other directions?

MM: No, no.

KP: Along the way we’ve mentioned quite a few people, Hernán [Vives], Julián [Galay], Sergio [Merce], Catriel [Nievas], and then I’m also aware of in your loose circle of musical friends Tomás Cabado and Nacho Castillo over at SELLO POSTAL…

MM: Yes, I don’t know Nacho Castillo. I talk with him by phone or messages but if you put two different peoples on the street I don’t know which one is him, but he’s a really good guy. Yes, Tomás Cabado, he’s a really good friend of mine. He wrote a piece for me, for the lute. The first album that I made on the lute that I told you that I rec here in the house I rec a piece from Catriel, a piece from Hernán, the last piece is mine, and Tomás wrote me a piece for lute but it was a really large piece and it wasn’t as experimental as I thought. It was a more traditional piece. I had to study a lot. He told me that he wants to rec, but I’m not gonna put it on my record, it’s gonna be a record of music that he’s making for different instruments, for theorbo for Hernán he wrote one, for cello, for the lute.

KP: Nice. Beyond them is there anyone else that you wanted to shout out or anyone else you play with frequently in Buenos Aires?

MM: Yes, I have a group here. Remember that album that you reviewed, Atractor?

KP: Ah yeah, Silvio [Moiz] too.

MM: I have a group with him, a guy that sings called Mariano Llere - he’s the guy that made that album that I reviewed recently - and a girl that plays the violin called Corina Guerrero, the name of the group is ENTE. It’s like free improvisation but we use a tale from Borges. We do a performance with the text, we all read the text at the same time, different parts of the text, you know that Borges loved labyrinths so we do like a labyrinth of words all the time. Really crazy and we’re working really hard with that. Ah, there’s a group that you should dig, they’re super super cool. It’s a duet called UDLI, la utilidad de lo inútil. They are two guys, a boy and a girl, they play with objects, they do things like [clinks coffee cup], they do the gigs in the place they rehearse. It’s an old house - [laughs] they are fucking crazy - and they say, OK the concert is gonna begin when you listen to this noise, and when you listen to this noise if you want you can get inside or not. But if you’re gonna get inside, you have to be really careful because you can hurt yourself with the broken glass on the floor, with the nails on the wall, you get inside a room with a broken piano with a lot of things hanging from the ceiling, a lot of things on the floor, and the concert is a performance that we all play. It’s like a huge improvisation. They are really good, because they play with space. They start playing with walls, on the floor, on the ceiling. It’s really really good, you should check them out. I think that I really like them because I think they are really genuine. They are not inventing, creating something new it’s like if you start digging you can find Mauricio Kagel, he used to do something close to that. But it takes a lot of work to do what they do and it’s not like a mimic. It’s not like it’s easy to do, like German minimalism, I’m going to play one note. I’m not saying that it’s easy to do that but I think that the amount of time that you need to prepare an entire room with things hanging, the idea that, OK my piece it’s my creation it’s the room, the sound it’s gonna be free. How you can give your music to others. The credit, it’s not mine, it’s the people that are playing, I’m just hanging things here. I think there’s a lot of art there. To play one note and everything just… eh I don’t know there’s people that they do that really really good. For example I know you know Fredrik Rasten?

KP: mmhmm

MM: Well, I love him. He’s like really really fucking good. I write them all the time saying, wow wow I really love this, I really love that. And I send my music to him to get feedback, something like that. And he does a lot of that one note stuff. But he has something. You don’t feel like plastic there. You feel like really huge substance in what he does. He does a lot of things. He inspires me in a lot of things. There’s a piece - remember that I told you I wrote a piece for seven guitars - when we recorded that I rec’d it with a microphone in the middle and we sat in a circle because I didn’t want to mix it and I took that from an idea of his, Six Moving Guitars. And I took that idea again for that piece that I told you about, the ensemble where we all play the same note and we move around the microphone. Those ideas, I didn’t steal them but he’s the first guy that I saw doing something similar, so he’s a huge inspiration for me. I told it to him because I admire him.

KP: Yeah it seems like even though what’s heard is quite different between maybe the duo with the house and Fredrik, they’re really both playing with something that’s important to you, which is the space, in different ways.

MM: Yeah, yeah, totally. So now that we talk about it, if I have to say something about me, it’s that I like to play with space. That’s it.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

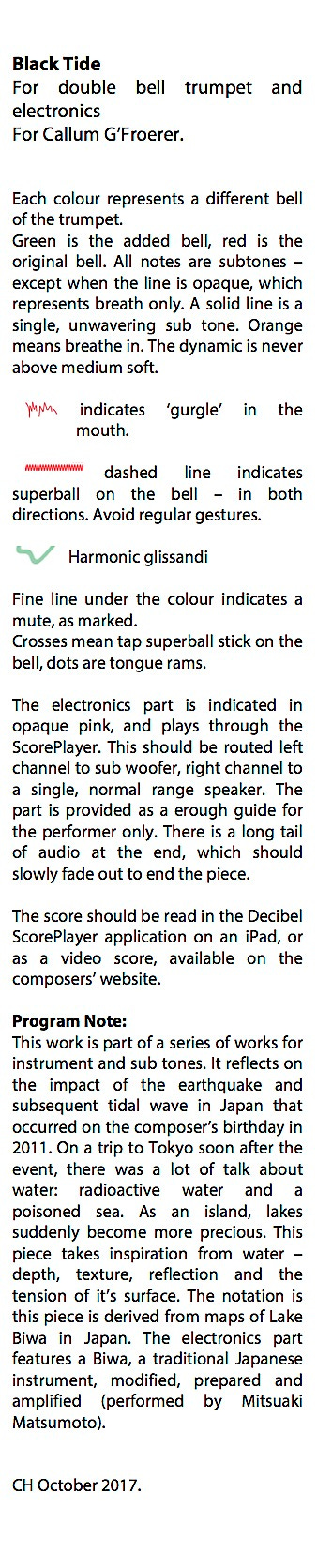

Cat Hope - Black Tide (2017)

Cat Hope is a composer, performer, improviser, sound installation artist, and scholar perhaps most associated with flute, bass guitar, and contrabass, whose music often embraces aleatoric elements, drone, noise, glissandi, and low frequency sound. Some collaborations include: Decibel with Louise Devenish, Stuart James, Tristen Parr, Lindsay Vickery, and Aaron Wyatt; Super Luminum with Lisa MacKinney; HzHzHz with Tristen Parr; Candied Limbs with Lindsay Vickery; as well as various film and art projects with Erin Coates & Anna Nazzari, Tracey Moffatt, and Kate McMillan. Some recent releases include Works for Travelled Pianos, performed by Gabriella Smart, and Decibel with the eponymous ensemble; Hope also maintains a running reference of several realizations on her site and on bandcamp.

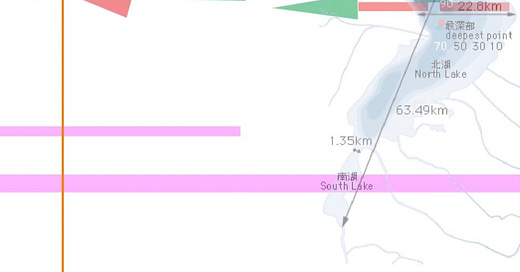

Black Tide is a 2017 composition for double-bell trumpet, subtone, and electronic playback. The work recalls the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami and the consequent heightened consciousness around the vitalness of unpolluted waters, like Lake Biwa, which is featured in the score and finds a mirrored reference in the modified, prepared, and amplified biwa performed by Mitsuaki Matsumoto in the fixed playback. The notes indicate the meanings of its shapes and colors - including opacity - through mixed symbols and text as well as just text. Words on the score signal dynamics and remind of techniques or equipment associated with some shapes, “softly,” “very soft,” “superball stick on bell,” “practice mute.” An elevation map of Lake Biwa and its tributaries overlays the final moments of the score. And, characteristic of Hope’s compositions, the score is in motion, with a vertical line indicating time. Hope’s video scores can be synchronously played through the Decibel ScorePlayer app for iPad and all of their associated files can be found in the appropriate DOI links on her compositions page.

The score determines overlapping relationships of techniques, their sequence, and the general means of producing sound but allows wide latitudes in the sound itself. Not just an alternative to flipping pages in the way digital tablets are often used, the score is intended to be interpreted in motion. Its frame-by-frame presentation undercuts the synchrony scores foster and places the interpreter in time, in the concerns of the moment. This diachronic approach might underscore that interpreters adapt appropriately within the field of the score based on listening to previous soundings, which feeds back into the flexibility of sounds allowed by the score and the greater emphasis on process over specific result in the instructions. In relating the score to its context, maybe the volatile, mixed technique of trumpet is polluted ocean to the serenity of the biwa subtone and Biwa Lake, or maybe the upper volatility and lower serenity symbolize the usual activity of a water column, like a lake, compared to the upheaval from the depths of Tōhoku. Breath could indicate a vitalness or wind fetching surface waters. Tongue rams pop like bubbles which might be associated with water, particularly near an interface with air. How interpreters choose to relate the symbols to the context likely colors their interpretations. But how to interpret the elevation map? Maybe it reinforces an imagination of the score as depth or water column and its movement as walking a cross-section, or maybe in providing dimension into the page it tacitly asks to accentuate its spatiality (which the instructions for speaker routing might also hint towards). Lastly, interestingly, the vertical line appears to indicate time only in the sense that it is a contingent collection of events rather than something on the clock. There is no duration written in the score materials, only provided by the default duration of the video software, the speed of which can be adjusted.

The realization below is performed by Callum G'Froerer, who also commissioned the work.

reviews

Alvear / Blanco / Carrasco - Mada (Modern Concern, 2022)

Cristián Alvear, Santiago Blanco, and Nicolás Carrasco perform a Taku Sugimoto composition with electric guitar, sampled guitar, and synthesizers on the 35’ Mada.

Some significant silences spot an otherwise bustling environment, twin synths an organic electronic hecatoncheires barrage reminding me of Ikue Mori’s instrumentation, splashed with guitar. Enough to recognize repetition reveals a relatively minimal selection of material. The quick attack and cut decay of guitar beeps. Discordant chords ringing. Propulsive trills. Eerie glassy swells. Stuttering sputtering feedback clicks. A rising reverbed melody refracting. Gravitational bass drops like dub techno double kicks. Cavernous dripping synths glitch. A slurred ghostly ambiance. Their arrangement appears random, disjointed. Though I have a hunch more careful construction repeats no combination to focus the nuances of color each material assumes in relation to others in each new combination. Or if a combination is repeated it is at least enveloped with previously distanced combinations whose new juxtaposition would recolor the perception of it. So something seemingly both repeated and random. Sometimes material shifts, gain climbs on guitar chords, bleep bloop parameters turn down reverb and turn up density, and while there are thresholds of plain change it asks to return to materials’ previous iterations to see if they were really changing all along. And like the eye drifts toward intriguing corners of an action painting there are similar fascinations in this abstraction that draw the ear, the strange harmony of guitar chords and eerie swells, the infectious off-kilter rhythm of click, trill, and bass beats, the chorus of a gain-forward chord and EVP whirr.

- Keith Prosk

Previous recordings of Mada include one from Ryoko Akama, Alvear, Cyril Bondi, and d’incise and one from Sugimoto and Stefan Thut.

Daniel Barbiero - …for double bass & prerecorded electronics (EndTitles, 2022)

Daniel Barbiero plays contrabass compositions and improvisations with fixed-media tracks of analog synthesizer realized by Ken Moore on the eight-track, 39’ …for double bass & prerecorded electronics.

The synthesizer sounds unfashionable, with an aura of seventies sci-fi spacestation bridge tracks, looped or played like loops through shifting parameters and textures or affecting aleatoricism through dramatic shifts in space and jumps in timbre. Stark contrast to the warmth and depth of acoustic contrabass. Which complements and presents counterpoint to the electronics through various methods. Rumbling vibrato for hashy crackle. Winding arcs bowed for buzzing bee paths. Staccato for stippling beeps. Something like the theme of Psycho for sirens. Hoarse nervous sawing and cascading pizzicato for electric sputtering. Matching texture, movement, relative register, speed, space to make this couple less odd. In a way it replicates the response required from acoustic musicians to early electronics and in doing so revisits the fundamentals of adaptive communication. Demonstrated vividly through three iterations of response to one electronic track, moving from melody bowed over it, to mixing in arco rhythmic repetitions eddying like electronics loops, to a plucked scalular lyricism with rhythmic eddies that synchronize with the bubbling electric beat.

- Keith Prosk

Pascal Battus - Cymbale Ouverte (Akousis Records, 2022)

Pascal Battus plays four pieces for cymbals and rotating surfaces on the 64’ Cymbale Ouverte.

The mechanism accentuates the action attached to sound, like a circular saw, attuned to the materials added to the system and their shape. Muting holding-releasing and tapping induce beats beyond resonant waves and various touchpoints generate distinct frequencies for tenuous melodies. As glass is viscous at certain scales, touching cymbals to the grindstone can nearly stress the liquidity of metal, shedding stridulations and harsh roars for warm purrs and clean singing. Sounds like sine waves seem to translate the periodicity of the mechanism transverse to the surface for ursounds in atomic orbital forms. Their rhythms transition like feedback, flashing a depth of complexity understood as distortion between dominant waveforms. But more often than this it is subtle shifts in noise, though a steady hand stays the kickback to conduct a symphony in the cacophony.

- Keith Prosk

DesoDuo - Songs for Two (self-released, 2022)

Katie Eikam and Kevin Good perform eleven companion compositions from Good on one vibraphone for the 60’ Songs for Two.

Their dynamics, tempo, and articulation are tender, gentle, and careful. Aspects especially emotive alongside shared resonances, dulcet melodies, and narrative structures and titles that convey the relationship of the two in tonal and physical space. “Finding” reflects “Going,” bowings converging to the same bar. “Sharing” means each mallets the same bar while one goes high, one goes low. A broken struck melody drifts from a steady stationary bowed drone in “Leaving.” The two move across the scale to nearly end where the other began in “Interweaving.” Effervescent mallets buoy each other, moving down the rail piecewise together, “Sustaining.” The long pauses punctuating “Waiting” find them further apart when they sound together again. “Following” finds one placing tones around - beside, before, just after - the other melody until it leads. “Forgiving” needs time alone as much as time together. “Trust” puts the performers close, shoulder to shoulder, crossing sticks even. And “Together” is one note bowed together for the duration. Structural simplicity evokes an earnestness in the emotion. Melodies on the metallic material given time to decay grant the comfort of music boxes or reverence of bells. Hammerings and bowings both cultivate complex harmonic relationships that reinforce the narratives, resonating together and beating as one in warm soft glows when in accord, leaden silent and cold when far apart in body and soul.

- Keith Prosk

Beyond the first frames in each video below, the scores can be viewed in the second volume of B-Journal.

David Friend & Jerome Begin - Post- (New Amsterdam Records, 2022)

David Friend and Jerome Begin perform eight Begin compositions for piano and its electronic processing on the 49’ Post-.

Dizzying dazzling phasing canons of cascading arpeggiated chords, mellifluous, flowing, amassing and dissipating like rolling thunder or in some limitless ascending spiral of accumulation make a kind of water music, momentous, turbulent, effervescent, at moments rippled through with tender twinkling melodies and hammered key plinks. Electronic processing usually subtly enhances organic aspects of piano, perhaps sounding something more than two hands can handle, accentuating harmonic glints, weighting piano’s low register rumbling for thunder with little celestial bolts of static, small squalls of clashing harmonics, a chorus of echoes intimating an impossible space for any piano studio. But sometimes its inorganic mechanisms manifest obviously, in effects too far from inputs, sustained for supernatural durations, with timbres totally immaterial to the piano. Contextually an argument for musicmaking tools as technology and vice versa, which seems obvious when said, but its implementation can recall cyborgs and then perhaps their potential pitfalls, though often villainous aspects of these beings are just code for other in science fiction. A call for open horizons on a few levels.

- Keith Prosk

Annette Krebs - Six sonic movements through amplified metal pieces, paper noises, strings, sine waves, plastic animals, objects, voice, a quietly beeping heating system and street noises (Graphit, 2022)

The most recent solo releases by Annette Krebs have been a treat to hear, each offering a new glimpse into a meticulously refined and impressively distinct aesthetic. Through years of experience and experimentation with elaborate electroacoustic systems she has managed to hone her sound with microscopic precision without detracting any of the improvised music’s instantaneous, spontaneous beauty. The sounds still all feel linked to gestures, and the gestures still all feel linked to an intent. What comes with this maturity is that that intent is not just that of a performer’s impulses and whims, it follows a plan, a process, a sophisticated intuition to arrive at its peculiar style and to paint its environment. The sterile, pristine, monochromatic atmosphere allows me to imagine that process as a dynamic medical operation in a science fiction hospital.

The sparse clanging, pops and fumbles that open the first movement remind me of equipment being set up and prepared. Ambiguous devices cling together as they’re dropped onto metal trays, cables and tools are organized, obscure equipment is turned on, initialized and tested, awkward pauses occur between each step. It feels anxious, uncomfortable, confusing, almost threatening. Metallic swipes and crunching textures enter from silence and leave reversed echoes, immediately deforming time in their absence, helping conjure an atmosphere of immaculate, high-tech surrealism.

The second movement is exquisitely soft. Faint, reassuring, non-threatening textures hang in the air and depart. Perhaps at this point an anaesthetic has kicked in. The unknown machines and gadgets still exist but are clouded by gentle static blurs, obscuring their nature and sanding off the sharp edges. The gestures sound professional now, rehearsed and precise. The elements stack into a decisive, blissful ambience that alleviates all tension and lures the patient into a controlled slumber.

In the third movement, the operation is finally underway. Sustained and repeated notes bleed over from the last movement’s therapeutic daydream fuzz and drill into my subconscious. At first its peaceful and comforting, the tones feel discreet and decisive enough to reach the cause of my anguish and pure and potent enough to cleanse it. The patient tones exchange between a human, emotional warmth and a mechanical, scientific cold, making for a realistic aura of healing. But as sounds repeat, cut out and restart, grow dissonant and distort, it starts to feel like this aura might not be working. It tries, it tries again, but it’s just not working, and what was once confident and alluring begins to feel feeble and ugly.

An aggressive thud ushers in the fourth movement, which plays out as a second, more aggressive operation. Metallic scrapes, smacks and cracks again invoke the preparation of unknown equipment, but a hurried pace plus a lack of compression cause the section to double down on the anxious, threatening vibe from before. The second operation begins with obscure electronics, clicking gadgets, a plethora of small, abstract sounds. This time it feels like several procedures at once, all with their own independent tools, procedures, objectives and sounds. It’s subtly overbearing. Layered, repeated sounds scrape and warp the brain, eroding anguish alongside all else and leaving an absolute mental null in its moments of silence.

The fifth movement is a recovery. After this rough, second operation, the soft tones from the first have returned, and are perhaps more sincerely comforting now than they were then. The initial section is drenched in dreamy surrealism, with rotating tones and processed voices that surround the listener and inaudibly deep bass that suspends them. Perhaps another anaesthetic has been administered. It’s a gentle world of rehabilitation, rest and observation. Slowly the hypnagogic atmosphere lets up and the listener awakens into a world of concrete, squelching sounds and tangible textures.

The final movement could be a return home. It begins with a tonal, technical descent, mirroring a nostalgic return trip from a future operating table which drops the patient off into playful, abstract vocalizations. Deconstructed speech showcases an idiosyncratic, personal style of communication that expresses its beauty and restored health with pleasant hums. This could be the patient back home, healthy, enjoying life, talking to themself, singing to themself – it’s a delightfully warm, human conclusion to a delightfully cold, alien performance.

I don’t want to imply that Annette Krebs intended this album as an analogy for a science fiction hospital visit. I think that is almost certainly not the case. I bring it up to demonstrate what I find so exciting about the abstract, sonic storytelling that can be found in this music. It follows emotional, thematic and sonic currents without ever suggesting a proper way to read them. It calls forth feelings and signals ideas that transcend easy explanations. It leaves me with thoughts and sensations that I can best understand with elaborate fantasies and unspeakable sentiments.

- Connor Kurtz

Jesse Kudler & Graham Stephenson - Apposite Rejoinder (JMY, 2022)

Jesse Kudler and Graham Stephenson combine amplified trumpet with guitar, radios, transmitters, tapes, and electronics on four improvisations totaling 35’.

Stephenson and Kudler remain committed, for the duration of this recording, to the overcast grayness on which they open, but what they seem to reveal, in the course of doing so, is the sheer kaleidoscopic depth and breadth of hue within that environment. It’s difficult for me not to hear the squeaked hyperactivity (almost ‘balloon rubbing’) of the trumpet(?) as a kind of ‘protagonist’ wandering through a ‘landscape’ gradating from windy or stormy weather to radio or TV static to industrial or mechanical sound. After an affectively resonant moment of respite suggested by stably-pitched and vaguely ‘minor-key’ tones near the beginning of the second track, we are thrust back into a world of ‘noise,’ navigating both sudden ‘turns’ and subtle ‘developments’ of complexly overlapping textures. What seems to be a final return to undifferentiated grayness near the end of the fourth track is undercut by the understated shock of seemingly-untreated human voices (and then maybe traffic?), reorienting my listening back to the concrete reality of live performance. Fittingly, after this refusal of perceptual stability, the recording ends not with calm mirroring its beginning but rather with a new variety of heavily-reverbed noisiness. As many moments of this recording trouble my perhaps too-‘classical’ narrativization as may seem to support it, but, regardless, what’s clear here is a particular density - not of sound, per se, but of ideas and of motion.

- Ellie Kerry

MAW - A Maneuver Within (Atlantic Rhythms, 2022)

Frank Meadows, Jessica Ackerley, and Eli Wallace freely play six environments for contrabass, electric guitar, and piano on the 43’ A Maneuver Within.

The stages of mitosis title five brief pieces followed by the sidelong “Decay,” suggesting a relation to the thought that all that lives is born to die, perhaps a nod to the geographic distance between the players after this session as a solid unit. Perhaps to its fluid musical character. It is an ooze. Timbres are as often anonymous as attributable through preparations, alternative approaches, and muting aspects of instruments’ harmonic profiles. Labyrinthine melodic lines muffled like monochromes of analytical cubism in propulsive strokes as gestural as musical lean discrete, angular, rhythmic. Sometimes supplemented with finger drumming, knocking, and other percussion. Despite this always a bed of deep harmony from double bass’ big body, the electric presence of amplification, and the reverberant harp. Sounds’ rings flare in this otherwise dampened atmosphere, selected harmonics bright like high tension steel cable or the imagined sound design of an arachnid crawl across its loom from inside-piano and electric guitar tone. Though their core remains, timbres appear progressively identifiable in the sequencing - walking basslines, clean riffs, conventional piano notes - coalescing. Perhaps to signal that the development of traditional technique is the death of sound.

- Keith Prosk

RLW - Tunnel (Sonoris, 2022)

Tunnel only mentions a single credited instrument: the voice of Annette Krebs. Via electronic transformation and virtuosic recomposition, RLW has successfully turned humanity’s most natural instrument into something wholly unnatural. The frequencies of the voice are scrambled and reassembled, syllables and words are tangled and contorted in time, and our primary source of communication is mutated into incomprehensible abstraction.

This concept is handled at its purest on the Voix pure tracks which book-end the album, two tracks made entirely of processed voice. RLW elegantly rolls Annette’s voice into an indescribable je-ne-sais-quois, tearing out all recognizable elements in favour of a mass of shifting textures – for the most part its unimaginable how these sounds could even relate to their source. It’s about 6 minutes into the piece that I can hear anything I can decipher as a voice. Annette is saying something, communicating something, but due to RLW’s aesthetic interventions it’s decontextualized and transferred into a new communication: from communication via words to communication via sound. The piece then finds a cautious balance of the two, where words might just be sounds and sounds might just be words.

The Sans voix tracks I find more difficult. On an album that only credits voice, on a song which promises to use no voice, it leaves me wondering what’s left for it to use? Nothing? The tracks are defined by undefinable textures, mysterious human presence and a lack of natural progression. They recall the most abstract moments of Voix pure, the moments that recalled the voice the least, effectively creating an aesthetic that can fairly be considered voix sans voix, a reimagined abstraction that houses the specter of communication. The aesthetic is both dense and hollow, it’s a complex, unfollowable exchange between voiceless entities. At times it pushes beyond the limits of voice by recalling deteriorated melodies and esoteric percussion, perhaps reaching past speech and towards a greater, more direct method of aural communication.