A Year of Deep Listening is in motion, celebrating what would have been Pauline Oliveros’ 90th year through sharing text scores.

Point of Departure’s 79th issue is available, featuring columns on Vinny Golia and saxophonists in isolated environments, an interview with Tomas Fujiwara, musings on the prose of Tristan Honsinger, reviews of John Butcher and Albert Ayler, and more.

crow with no mouth radio episode #52 is available, presenting a couple recordings of Terry Jennings’ music including the recently released realization of Piece for Cello and Saxophone with Charles Curtis, with whom Foxy Digitalis recently had an interview surrounding the same subject.

An intermittent reminder that we welcome composers to reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for more information if they’re interested in featuring their non-standard notation in this newsletter. We offer payment for pages.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $2.15 to $11.49 for May and $0.35 to $1.40 for June. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Lisa Cameron is an improviser and rock drummer based in Austin and perhaps most associated with percussion, feedback, and homemade instruments. Over some dolmas and drinks we talk about those homemade instruments, imagining sound, practical boundaries, ritual, psychedelia, approaches to improvising, differences among improvising and rock, and Texas.

Recent releases include See Creatures Too with Sandy Ewen and Window To The Spheres with Suspirians. Place is the Space with Ingebrigt Håker Flaten, Jonathan Horne, and Joshua Thomson will release shortly.

Lisa Cameron: So what do you want to start with?

Keith Prosk: I’ve got a couple threads that I’m thinking about but always feel free to take it any direction that you want. So I guess one of the first is that you… so you do a lot. There are some people that know you as a percussionist, a drummer in both rock settings like ST 37 and Suspirians and stuff but also your different improv groups. And I know you play some lap steel. But there’s also this whole world of created instruments, repurposing the kit for feedback systems, or the berimbauophone, or the mortal coil. So what are some of the motivations behind creating new instruments?

LC: Well that is an interesting question. I’m always on the lookout for ways to make new sounds, so I figure that just making a new instrument is the best way for me to customize it the way I want it. I’ve been working a lot with resonant surfaces. Before I was working a lot with resonant frequencies and rooms and now I’m working on resonant surfaces and how they react with each other like, say, drum heads, pieces of glass, steel string, springs, wood, metal. I’m starting to look into different types of mylar, how that might work being stretched like a drumhead.

KP: What is mylar again?

LC: It’s this really strong metal that’s… it’s like aluminum foil but it’s really strong so you can stretch it out a lot and you could probably use it as like a drum head or something like that.

KP: Is that like Tyvek type stuff?

LC: No it’s a thin membrane. It’s used in… I think it came out of aerospace technology. It was a big thing for awhile, you know, ah mylar. I think it’s still around in science equipment houses, you can get a lot of really neat stuff there. So the main thing that I’m trying to do… I’m trying to do two things now. How to make drones acoustically, and I’ve been kind of pursuing that for a long time. And then what I want to do is try and use all these different textures and weights to make drum heads and see how that affects the resonant quality of it. ‘Cause if you can tighten down a drum head really tightly you’ve got a certain amount of bounce there when you start something vibrating but there’s also a looseness to where it catches in or does the right amount or the most amount of oscillation… we’ll put it that way. So I’m just looking for different ways to do that.

KP: That’s awesome. Are you still using like a drum structure, like a circular drum?

LC: Probably. I haven’t actually started doing it yet but that’s kind of my next project. And the thing that I’m working on now is taking the mortal coil on the road somewhere and I have a possibility of an installation in New York this Fall. I’m gonna try to pursue that.

KP: So what is exactly the mortal coil?

LC: OK so that’s a thing that Brian Johnson from Cloud Tree Studios… he’s an artist and a jeweler and a woodworker, he can do anything… so he commissioned me to do a performance with him together on something that we collaborated on. So we collaborated together on making it and he pretty much knew all the physics involved and then I applied it with electronics. And we did a show at his gallery about four years ago, something like that. So we made a twenty foot long piece of conduit about an inch in diameter with ball bearings inside. And what I did is just stretch that out because conduit comes in a spiral or a coil, so I just pulled the coil out and I attached two different pieces so it was twenty foot tall and I just bent it out and attached it to the wall. And then I was thinking of using compressed air to make the ball bearings go all the way up to the top and then come back down twenty feet. Brian got the idea to use a garden timer to time it so the compressor would cut on at just the right time and it would blow everything up to the top with the compressed air and then the compressor would cut off and the ball bearing would fall back down. The falling is tracked by all these different contact mics that were attached to the coil. And then I put the contact mics and sent feeds through a mixer and had speakers in each corner of the room. That was pretty amazing. I got some really good sounds out of it. It sounds kind of like breathing… like a dragon breathing or something like that. I tried it out different ways, soft, loud, changing the pressure so it took more time to go up. And then Brian helped me with this, he helped me figure out how to time it, how to even attach a timer, a garden timer to a compressor, which I had no idea so… he really helped out with that.

KP: And you said it sounds like inhalation exhalation, so it just sounds like a really deep glissando going up and down and then you’re kind of making waves on the mixer?

LC: Yeah so just like [swooshing sounds] and I had it to where it would come down faster at the top and then go slower because I had it going down more to a cone, so that changed the descending speed of the ball bearings. I want to investigate that again but I really haven’t had time for the last couple years, or I’ve been so busy with other things. So that’s the next thing I want to put my attention on, is trying to make that more of a mobile type situation.

KP: Yeah. Have you envisioned a portable version or is it almost required to be an installation instrument like Ellen Fullman’s Long String Instrument?

LC: My plan is to do a table top version with it this Fall. And maybe if I can do some shows with Sandy [Ewen] maybe I’ll include that. Because what I do, I make these instruments and then I move on to the next thing so I think I’ve used the berimbauophone as much as I want to. Right now I’m just using the resonator and putting different things on it but I want also to move on to this pneumatic stuff that I’m just scratching the surface with.

KP: That’s awesome. And with at least the couple of records that you’ve got with Sandy, you have used the berimbauophone. So what is the berimbauophone and is there a particular reason why you’ve decided to bring that to your duos with Sandy instead of your kit or feedback systems?

LC: The berimbauophone has an interesting backstory. One day my partner Lee Ann came home with a wooden box that she had found on the side of the road that was made out of nice resonant wood, I think birch. I first began using it as a type of cajon, and then started noticing that the surfaces picked up sounds quickly and began to place contact mics on it. Then I decided to somehow attach a berimbau, which is a Brazilian instrument used by Amazon shamans in the bush to catch spirits, as well as being used as background for a martial art known as Capoeira Voila, the berimbauophone! I only recently have used a kit or percussion to record with Sandy. The only released things that I’ve done with Sandy were done with the berimbauophone basically. When we did a short tour earlier this year, we did a little tour and I just used the resonator and percussion because the berimbauophone, well, it was inconsistent from day to day depending on the type of room I played it in. Instead of going to what the berimbauophone was about I just wanted to go to the phone [laughs] so I took the berimbau out of the equation so then currently I’m just using the phone and… you know what I mean by phone?

KP: Yeah the membrane, so the box.

LC: Yeah it’s an idiophone which is a stretched string attached to a resonator box that’s used. Like the guitar is an idiophone or, say, a gutbucket bass is an idiophone.

KP: Yeah I feel like the berimbauophone… it actually reminds me of a boy scout bass, like where you attach a stick to a bucket and put a string tying them…

LC: It’s very much like that. But I was just thinking… you know, I was having trouble actually using the bow as much because it would fall down for one thing. It’s just held up by this elastic string and I’d tighten those down with cleats to where the cleat keeps the constant tension but I’d be setting up for a show and then something wasn’t working and I couldn’t get it to work. I just didn’t have enough time to do it so I thought, well I’ll just take the resonator. So what I do is put different weights on it and move the weights around. Contact mics are attached to the box with C-clamps or different types of clamps that I have. And then the actual pressure on the contact mic makes a difference, the placement of where the contact mic is on the surface makes a difference, whether it’s on top, on bottom, or the sides makes a difference. You can put the contact mic onto the C-clamp and push enough gain into it to where you get a sound. And then you put small objects on top and then those start making their own harmonics…

KP: Didn’t you… did you have a streamed performance in the past year or so that showed this?

LC: Yeah, with Sandy.

KP: That wasn’t the New Music Circle one was it?

LC: ESS. The New Music Circle one, that was pretty much when I was doing drum feedback in combination with the berimbauophone. Because the drum feedback sounds good with that as well. So you know I’ve just kind of… it’s just like, take this and take that and see what works, what combination. I like to change the combination because I get different sounds. So nothing ever sounds the same. I just did a show in San Antonio using that and it went pretty well, just moving objects around on top or inside the box. And you know playing them or moving them around, sometimes you can just move them around and cause huge shifts in the harmonics, just by moving one object to another. And also the weights, the different weights you know are interesting. I have light things like shells or heavier things like a glass candle holder. I have a lap steel bar they use to play on a lap steel, those are pretty heavy and they’re also concentrated, it’s a piece of steel so you can move it around and, say, move this piece of steel here and move this other thing at the same time or at other times, just depending on what I’m hearing. Since I’ve been doing this a long time I tend to react pretty quickly.

KP: That’s awesome. I feel like whenever I envision music I envision a two-dimensional thing, like a string going up and down in a wave, but it feels like with the tabletop it’s more of a dimensional thing and I’m kind of envisioning like, you know, all those figures that explain Einstein’s theory of relativity or something where it’s a suspended blanket and you have a big weight over here and a small weight over here and how that changes the surface shape, not reflected physically but reflected sonically. I guess you mentioned… I was kind of aware of it with your drum feedback but you mentioned it with the mortal coil and other things as well, you mentioned finding resonances in the room. So I know that’s a big concern, is finding what works in a room, what doesn’t, the natural resonance of a room. Once you find the natural resonance of a room are there some ways that you tend to go from there? And also are there some special concerns that you play around with or adapt to as far as the shape of the room, the material of the room, the size of the audience and how many water bags are gonna be in there [laughs]

LC: [laughs] Yes, all of that. Well when I first started I was super primitive and I just used an amp and a contact mic and a snare drum and I became really obsessed with how to… harness a sixty cycle hum of an amp and I’d be using that to excite the drum head and the problem there is you excite the drumhead… or you get the sixty cycle hum and then there’s a threshold. And if you go past that threshold it just makes a hideous squealing sound. It’s a threshold, it just can’t go any further and it just squeals. And that’s, you know, if you do feedback like a feedback guitarist or something it’s just gonna do too much and you’ll lose whatever nuances you’re trying to get. So with the snare drum it was pretty difficult just to sit there and use the amp to control the snare drum without… making it sound interesting and at the same time not sending it into that squealing mode, which was always very embarrassing. Because you know you’re sitting there, the audience, people are looking at you, this thing’s squealing and you have to wait… it’s destroyed every place that you’ve gone. But I developed that technique doing a lot of noise shows and in noise shows it was kind of like hanging ten on a surfboard. It’s about how far can you go before making it squeal. And I would definitely have people waiting for it to happen and could hold it back from doing that.

KP: I guess the way I’ve envisioned it, but I haven’t messed around with things enough to actually get a good sense of it, was kind of what you alluded to with ruining everything before, is that in order to get to a certain place you can’t just turn your knobs or whatever to a certain direction and it always happens, there’s a sequence of actions that you have to do to get there and you have to layer things a certain way to get to a place.

LC: Yeah. And then as you said before another thing was the structure of the room, how many people were in it. It would always work better when I was just using an amp to use some place that had a wood floor. But that’s pretty hard to find, especially these days. You know, you’re touring, you’re going to different places.

KP: The expense now. Now it’s all like composite ‘wood.’

LC: Yeah, so… enter the mixer. I started using the mixer. And that took care of those problems because I could set up the eq to where I could make sure that those things would happen. That freed me to be more attentive to what was going on instead of just trying to hold back, I mean, the inevitable [laughs] That’s kind of weird I guess but the kind of things that go on in my mind. I have no idea why I do this, I just started doing it…

KP: Yeah, there doesn’t necessarily have to be a why. I guess when you do approach a new situation or a performance, how much is planned ahead? Like do you write anything down as far as directions or structures…

LC: Absolutely nothing. And that’s how I always improvise too. I don’t talk with the person that I’m improvising with about what we’re gonna play. And that seems to work out better for me that way.

KP: And then with your improv groups like, I don't know, the Tom Carter / Ingebrigt [Håker Flaten] one, do y’all jam at all and coalesce towards some tunes or it’s all just straight improv…

LC: [shakes head] like the new one that I’m working on that we recorded last year, it’s amazing. But we just went in and we did an hour and a half. We got a place in Denton, went in, did an hour and a half straight. Didn’t even talk about it. That's pretty much how I improvise. I remember seeing Jack Wright play here in Austin in the eighties and it really impressed me that he just played completely in the moment. And Ingebrigt was over here a week or so to take care of some business from when he lived here so I said, OK let’s do this tour. So Tom and I and Ingebrigt, we played a couple of shows. We didn’t play a show here, I don’t think. Yeah, we played in Dallas, Shreveport, and Houston. And so now I’m editing those files right now and it’s due to come out as a vinyl record on Astral Spirits some time next year. But it’s very good. It’s very different than the last time we played together.

KP: Yeah I imagine so if you, you know, don’t talk about it.

LC: Yeah we don’t talk about it. And it seems to me that’s how, everyone that I do things with, that’s how it is. I was just reading the new article, the interview you did with the contrabass clarinet person…

KP: Yeah, John McCowen.

LC: John, yeah. That was really interesting because he talked about how Roscoe Mitchell improvises and then transcribes it. And I didn’t know that. Actually just read that this morning. Maybe I’ll do that, I don’t know. I don’t really transcribe things, and I don’t know how I would transcribe stuff that I do but you know it’s a possibility. So far I’ve been able to just walk into a situation like, say, when I recorded with Damon Smith and Alex Cunningham, it was the same thing. I was terrified because I’d never played with… I had played with Alex a little bit…

KP: Oh interesting, you never played with Damon when he was in Texas?

LC: Never played with Damon before but always loved what he did. And I was just terrified like, I can’t believe I’m playing this. And we didn’t even set anything up and we just went into the studio completely cold and we hadn’t even played yet, at all. That actually came out pretty good, that was Dawn Throws Its First Knife. That came out really good but listening back to it I was kind of bewildered… but I think it came out well. We recorded again a couple of years ago and that one’s going to come out I think on Alex’s tape label [Storm Cellar]. That one’s really good. Since we had had a history of doing a few gigs and playing in the studio, it worked out well.

KP: So I imagine that kind of approach is not what ST 37 does [laughs] Are there ways in which the more rock way of doing things communicates with the improv way of doing things that you wouldn’t expect and also ways that they clash where you expect they would not?

LC: Well I’ve been in ST 37 for longer than any other group and we just know each other really well and we have a knack for… I mean, we’re trying to extend the language on space rock, you know, envisioned by Chrome or Hawkwind or Can or Ash Ra Tempel or whatever. That usually involves, as far as I’m concerned, keeping a motorik beat or some sort of pulse that they can do whatever with. So that’s a totally different thing because I don't play beats with these improv groups, I try to avoid them. The more I can avoid them the better. And certain things like, say, The Suspirians or ST 37, those are based on traditional rock beats. I always try to think like, what would Damon Edge play or what would Jaki Liebezeit play on this song or, you know…

KP: Double kicks [laughs]

LC: [laughs] I don’t have any double kicks. But you know a lot of that stuff still works really well in the framework of ST 37 because it’s mostly about the guitars and not really about the drums but with the improv stuff it’s more like a equal footing type of thing. And in Suspirians we’re doing a lot of improvising now so I play a lot of electronics and drones in Suspirians and Marisa is playing guitar and electronics and Stephanie is playing bass and electronics and she’s branching out into prepared guitar and things. That somehow translates into a nineties kind of rock thing too. That’s a group that is kind of even less tangible than ST 37. When ST 37 gets together we know pretty much what we’re gonna play like, OK they take off on the guitars, I provide this fat beat that they can play on, you know. So I’m OK with that it’s just, you know, it all has to do with how well the musicians get along and how they work together. ‘Cause I don’t like to work with people that aren’t good to work with. I had a history of that where before I started doing improv or this kind of thing I would get in bands where there was a lot of top-down ordering like, you play this, this is what we need to play here, this is what’s gonna work in this song. I don’t do that at all. I suppose if somebody gave me, you know, $500 to do a recording session and told me what to play I’d probably do it but that doesn’t ever happen so… not that I’m saying I have to get paid to do that but that’s just not what I like to do.

KP: Yeah. So if I look at some of your collaborators it’s like a roster of excellent central Texas based musicians, like Tom Carter, Ingebrigt, claire [rousay], Lee [Dockery], so I guess you answered one part of what I had in mind, like it’s more about the people than anything else, playing with cool people, but is there a conscious decision to keep it local in like an Eddie Prévost way or is that more of a circumstance thing like travel is costly?

LC: Circumstance. No I’d love to do more traveling but I mean right now in Texas it seems like… the most interesting music right now seems to be going on in Denton and Houston.

KP: Rubber Gloves, yeah, and MECA and everything Dave Dove is connected with, yeah.

LC: Yeah those two. Right now in Austin there’s Melissa Seely's Me Mer Mo Monday and Epistrophy Arts just did a very well attended show with Andrew Cyrille and Billy Harper. San Antonio is beginning to do more improv or noise shows there as well.

KP: I guess this is circling back around to the instrument building part. I think I’ve heard that you actually do handy work right like home maintenance…

LC: Yes, but what even relates more though to my soundmaking is my experience doing body work and massage. I’ve had a practice for twenty something years doing body work and massage and I have really put a lot of impetus into that.

KP: Nice and that feeds into the instrument building?

LC: Because, well, I work with changing fluid pressure in the body. There’s a technique called craniosacral therapy and I do that and I also do these other things that are related and they’re all about changing pressure in parts of the body. And it’s a three dimensional thing. Body work goes through the body. We’re a sac of water basically. And that’s resonant, it goes through the whole body. So say there’s a… you know, the law of hydraulics says you press in here into a body of water it’s going to displace just that amount in another area.

KP: Yeah it’s incompressible.

LC: So I learned through that, just working with people. And seeing how this worked I thought, well maybe this would work with sound.

KP: Yeah it almost sounds like the box, table.

LC: Mmhmm it’s all about sound pressure, pressure of the waves.

KP: I mean I guess sound waves are pressure waves too [laughs]

LC: Yeah I did an experiment one time where I had these amps - it was Church of the Friendly Ghost - and I had these amps, I had these blankets over the amps, and I just had them feedbacking and I would gently lift the blanket and it started changing as I lifted the blanket, because the amount of air pressure coming out was changing and that changed the sound. That was pretty interesting. So I did that a long time ago and that’s when I first started using my body work skills connected with my music.

KP: That’s awesome. It’s almost like the body is the room. That’s the container, right, just displacing waves through it.

LC: Uh huh [laugh] never really thought about that but I guess so. I always like this legend, there’s a Navajo legend about the two twins at each edge of the world who keep a vibrational continuity. One is the south pole and one is the north pole and they’re connected with this vibrational field. Keeps everything humming on the earth. I kind of resonated with that.

KP: So I guess whenever we talked about a year ago you mentioned a bit about ritual and I remember Changó for instance was brought up but how do you think of ritual when you’re playing?

LC: Oh god [chuckle] you know, everything that I do is a ritual, I think. I’ve kind of immersed myself into that world where I don’t think about it anymore, it just happens. And I think that has more to do with my body work abilities. But then that carries over into everyday life. And for a long time I did qigong and tai chi and I found that tai chi isn’t just a physical thing it goes through your entire being, consciousness, the way you approach things. The way you shift your weight has to do with the way you shift your mental weight, or your emotional weight, or your physical weight, or your artistic weight, any number of things. I just stopped trying to cut off ritual from being at a certain place, so for me almost everything is.

KP: It’s just there.

LC: Mmhmm I’ve done a lot of reading about different things like thelema and voodoo and gnosticism. It all ties together.

KP: Yeah. So this is gonna be a bit of a rant… not rant… so when I think of ritual it’s kind of like an inbetween space where certain actions are happening to get from one state to another and I feel like that’s very similar… and that can be quinceañera or funeral or whatever but a lot of times it’s portrayed or sometimes even carried out through a very psychedelic means. And you know just coming from ST 37 which has its place in Texas’ noisy strain of psychedelic rock with like Butthole Surfers and Charalambides…

LC: Yeah we used to play shows with Charalambides back in the day. I remember seeing Tom Carter playing at Sound Exchange with Mike Gunn. He was probably eighteen when I first saw Tom play. So it’s been a long relationship yeah…

KP: Yeah but I guess even though… and I mean in a certain way feedback stuff, what you do with the drums, if it’s a long enough duration you can kind of sink into it, or if sometimes the beatings and the harmonics are so complex it invites enough focus to where people can forget themselves, be outside of there bodies…

LC: It’s psychoactive.

KP: Yeah, so is psychedelia a conscious part of what you do?

LC: Yes, definitely. I’ve done my share of hallucinogens. Everybody in ST 37 has. Tom has. Not everybody that I work with has though. You know it’s not a focus, the door’s already open. When I was in Denton in the seventies that’s when that was like pretty focused and that’s when I started listening to that type of music. Particularly Art Ensemble of Chicago or Sun Ra or Terry Riley or Steve Reich or La Monte Young. Been listening to a lot of La Monte Young lately because I went to see the Velvet Underground documentary and he was in it and I was like, oh I need to listen to more of his stuff again. So I have like, The Well-Tuned Piano. To me it’s just amazing. A lot of people would just say, well that’s like listening to paint dry. Well maybe so [laughs]

KP: Well maybe that’s interesting [laughs] I feel like you’ve mentioned the John Cale and Sterling Morrison reissues on Table of the Elements too, their feedback stuff.

LC: That was what got me doing Venison Whirled. ‘Cause I heard that and I just thought I wanna do something like that in that context, where it comes from the sixties context of using a crude amplifier or microphone and instead of doing it with a guitar though doing it with a drum. I guess in Denton I was doing a lot of experimenting with sounds when I was in college. And I put a contact mic on a bass drum and I got this hum and I was like, wow if I push this up and down it changes the pitch. So I started doing that with different drums and cymbals and you know I would do this thing where I would put a contact mic on a metal shaker and then put it through a giant Sunn amp and just turn it up and it would sound like a space ship [laughs] I was like, wow what is this. And of course coupled with just the time, you know, in the seventies when you didn’t have to do much work and you could live off barely anything. I was just playing gigs with Brave Combo, doing that to make money, and then the rest of the time just experimenting with sound. It was great. I don’t really have time to do that much anymore. I have been some like during the pandemic I was able to do a little sound experimentation. But hopefully that’s coming up soon too, where I can do more of it.

KP: Yeah and you said it’s in everything you do but I imagine building new instruments and finding those new sounds also carries along with it some of the strangeness that’s required for a psychedelic experience whereas sometimes the kit, it feels too familiar to really take you outside of yourself maybe…

LC: Uh huh. Well, I’m trying to get to where the kit will do that. Right now I’ve also been going back and listening to my drum heroes and just finding the magic that happened with like Max Roach or like Andrew Cyrille or Kenny Clarke, you know, Baby Dodds, the list goes on and on and to me they were doing a ritual, it was a ritual. Because it was so concentrated of an energy. I don’t know if they realized they were doing it…

KP: There’s definitely certain moments… like you mentioned Liebezeit, “Halleluhwah,” just that whole track, or something that I always think about a lot when it comes to the drums is the cymbal crash on Sly and the Family Stone’s “(You Caught Me) Smilin.’” There’s something about that crash that for those few seconds it takes you to a place that the rest of the song doesn’t.

LC: I love those Sly and the Family Stone records. One of my favorite records is There’s A Riot Goin’ On and I think that’s a record where the drums are almost perfect. They’re almost perfect. The drummer was the guy who used to play with Santana. He played keyboards with Santana but I think he played drums with Sly, and I think Sly played drums on it too. And so I remember when that record came out I was like, wow this is so good. And I still listen to it and I still marvel at the drum tracks. There’s a lot of that in r&b. I’m a big New Orleans r&b fan and some of my favorite drummers are r&b drummers, blues drummers, just all kinds of drummers.

KP: I mean I can’t think of a drummer off the top of my head but just those studio players like James Jamerson, it’s hard to beat.

LC: Yeah that’s some insane stuff. That’s really… there’s a magic there. And so I want to reconnect with that just playing the drums. And so I’ve started to do that. I’m trying to focus more on just playing drums. I’m also wanting to do the other stuff too. But you know there’s time for everything. I guess the main thing now is that I want to get the mortal coil portable so I can take it on the road. I don’t know how that’s gonna work out but it might. It might work out great. I could have two of them going or three of them, I don’t know. I just wish I could get some money to do it… I’m kind of excited that I’ve been invited to do this possible installation. That might be possible in New York this coming Fall.

KP: Nice. I’ve heard that Austin just restructured its arts funding but have you ever… I don’t know how easy that is to get, I know that Bob and Chris and Ingebrigt have gotten it but is that possible for musicians or is it mostly for presenters?

LC: It is and I keep toying with the idea of getting involved in that, I just haven’t done it yet.

KP: Forms [laughs]

LC: I know Chris is good at it, so I’ll probably be talking to him about it. But I’ve heard that there’s less money now because of the pandemic and the city doesn’t have as much money as it did. Just the Austin gentrification blues shuffle. That seems to be what’s going on. Now I may have to leave Austin just because it’s getting so expensive. I may have to sell my house, you know. Since I bought a house twenty years ago, I have lots of equity, I might start losing it if the bubble bursts or whatever, who knows.

KP: Yeah the same friend I was talking to last night said that he got his house I think in 2006 for like the 200K area and now a house by him just sold for four times that it’s just like [laughs] can’t keep up.

LC: It’s kind of hard to ignore it. I mean, I bought this house for a hundred and nine thousand in 1996. It’s worth like… I could possibly get a million dollars for it. But should I just sit on it, I mean, I need money to live there. It’s almost like they’re forcing me to sell it because if I don’t then I have to pay these exorbitant property taxes.

KP: It’s just hitting that 10% cap every year.

LC: It gets higher and higher and then once you get to ten thousand dollars then you don’t get a deduction on it.

KP: Oh I did not know that.

LC: Thanks to Donald Trump. That was a little thing he put in the IRS.

KP: That seems like it would hurt the rich more than help it which seems odd for him.

LC: But yeah so that’s kind of my future is like well, am I gonna leave Austin. OK if I leave Austin where am I gonna go.

KP: Denton [laughs]

LC: Denton, well we’ve talked about it. San Antonio, Elgin, St. Louis, Tucson, Silver City, I mean I just don’t know. And also the fact that it’s getting hot here. It’s gonna be 104F this week.

KP: Yeah just the variability. I feel like last year it was super wet, this year’s bone dry. We’ve had snow the past three winters whereas before I saw snow maybe once in my life [laughs] the variability is hard to deny as far the climate change. Texas is getting wild and not just in the weather.

LC: Ah yeah there’s that too. I think it all depends on the November elections for me, which way it goes in November. If it continues where it’s going, where it’s been, I may just have to leave because I can’t live in a state where they treat people like that.

KP: Yeah, just hopefully enough people vote to not have [Dan] Patrick and [Greg] Abbott.

LC: Who are basically minority rule. I mean it’s a feudalist society that we have here and they’ve just kind of done it through stealth.

KP: Yeah, gerrymandering for the rural minority… I guess that’s all the directions I laid out but did you want to go anywhere else?

LC: Sure I guess I can talk about some projects that I have coming up. Well, let’s see, I have a tape coming out next month on Personal Archives, which is Bob Bucko’s label, and its called Place is the Space, and it’s Ingebrigt, Jonathan Horne, Joshua Thomson and I. We just got together at a studio during the pandemic and just recorded and it sounded great. You know what I thought was gonna come out was a lot of anger and intensity and energy but what came out was just really nice kind of even tone, almost calm. There’s a little bit of energy on it but it’s not like screaming for help. I think we were using the music to just kind of calm things down and reassure ourselves and whoever hears this that, you know, things are rough and it’s easy to get angry about it but it’s also good to keep an even temper about it. You know there are a lot of people doing energetic stuff now. I was kind of surprised that that’s where it went but it was really nice. I have a new recording with Ernesto Diaz-Infante that will be released on Loma Editions, a new all percussion tape on Weird Cry with Raquel Bell and Jared Marshall, also about to work on a new Ganjisland recording with Raquel that we recorded last year. ST 37 is working on a new album and it’s a tribute to J.G. Ballard. Because we’re all science fiction fans so every song is related to a J.G. Ballard story or book.

KP: Literally space music [laughs]

LC: [laughs] So that should be good. We’re gonna finish that up pretty soon and then who knows what’s next. I’ve been doing doing some shows with Danny Kamins and Thomas Helton. We’re supposed to do some recording, and I'm soon recording with Aaron Gonzalez and Rick Eye. We have a no wave noise trio called Unrelenting Psoriasis [laughs] and then I’m doing a trio with Jessica Ackerley and Eli Wallace in the Fall. We’re recording and doing a short tour here in Texas. I’m real happy about that and I’m real happy that she still wants to come here and do this but it’s only for a couple of days. I think it’s four shows and then we’re supposed to record in Denton. That and then, let’s see, hoping to do some more shows with Sandy in the Fall in the northeast, and possibly more with Drew Wesley, Seth Davis...

KP: And with the coil.

LC: And with the coil, maybe. Hopefully some more shows with Alex and Damon. And I don’t know if we can get Ingebrigt over here or not, he lives in Norway now.

KP: Is he permanently back in Trondheim?

LC: Pretty much yeah. I think he’s doing well over there. Just played this crazy thing with Joe McPhee and Jeff Parker and just playing with all these different people, it’s amazing.

KP: Nice. I saw Sonic Transmissions, one of their records got featured by Peter Margasak somewhere in, I don’t know, quietus or bandcamp or something.

LC: Oh, great. Recently?

KP: Yeah I thought I followed Sonic Transmissions but I guess I missed it. But yeah it was nice to see Ingebrigt’s label getting some recognition internationally… not that he’s not an international player, he’s all over the place, but [laughs] I don’t know…

LC: He just keeps… his star just keeps going up and up, it’s great. I hope to be just staying busy wherever I am. I’m sure I will be. And I have other ideas for things I wanna build that are a little bit more daunting to try to figure out how to do it but I have some great ideas for things involving snare drum feedback.

KP: Yeah just keep on chipping away at finding new sounds, new territories… sonic frontiers.

LC: Yeah what I’ve always done is I’ve tried to just keep doing that. Never get too comfortable, never fall into a niche, never actually let people know what I’m actually doing. Because once you define it then you have to move on, or I do anyway. That’s how I feel, once I’ve done something I want to move on and do something else. I’m not somebody who just goes and listens to what I’ve done hardly at all. But I just feel really blessed that I’m working with such an amazing pool of talent of all types. I’m sure that some of them would be like oil and water but they all fit together in my particular sphere. Works out that way. Just like being able to play these incredible things with Sandy and just… we do this music and then we try to figure out what it sounds like. So we thought, well it sounds like creatures so we made up these creatures. The first one they were actual creatures and then the second one well the whole thing is a play on words, See Creatures, and so we see these creatures while we’re playing the music.

KP: You’re telling me there’s not a bananasaurus [laughs]

LC: [laughs] maybe. In some dimension somewhere there’s a bananasaurus. Sandy thought that one up, I thought that was cute. She’s so playful with her sense of humor, she’s really fun to work with. I should mention my son, Dylan Cameron, a fantastic modular synth player. He is really good at playing synth live in real time, and he also masters, records, and mixes music in his studio. He's been working for the Holodeck label for a long time and he mixed and mastered a lot of their releases. He’s mastered just about everything that I've released and he’s working on mixing the upcoming thing that I did with Ingebrigt and Tom.

KP: So did he master like the Stranger Things theme? The group that did that, they came from Holodeck but I imagine everything else was not in their hands…

LC: No, I don’t think he mastered that one. He did master quite a few other artists on Holodeck and they've released some great records of his. He also works with different rappers from Europe, you know, he just likes to keep moving like me. I have one that I’m still trying to work with, it’s just a few modules that I like to use, but he has one of those giant setups. And he collects keyboards and synthesizers. Pretty interesting guy. He’s a lot like me, as in dealing with what’s next in Austin, trying to navigate the fantastic sea of music that it's always been, and pay the exorbitant rent, which is always keeping you on your toes here. I like to call it the "Austin shuffle.”

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in harmonic series are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this presentation only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in harmonic series, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Jaap Blonk, five samples

Jaap Blonk is a composer, performer, and poet perhaps most associated with voice, live electronics, and visual work, whose music plays at the limits of vocalization, communication, and translation. Some recent collaborations include: Jaap Blonk’s Retirement Overdue with Miguel Petruccelli, Frank Rosaly, and Jasper Stadhouders; JeJaWeDa with Jeb Bishop, Weasel Walter, and Damon Smith; a duo with Terrie Ex; and various constellations with Udo Schindler, including the duos Hillside Talks and Lakefront Discussions and The MunichSoundStudies Vol. 2&3 with Damon Smith and arToxin_08062018 with Elliot Sharp. Recent releases also include the solo Ingletwist Fragments, released through the Catalytic Sound Collective of which Blonk is a member, and contributions to Elisabeth Harnik & Didi Kern’s Steamology. Blonk runs the Kontrans label too.

I think together these scores convey a playful approach that when performed are often humorous, sometimes absurd. The building blocks of language, principles of translation, and the vocalizing entourage of intonations and gestures blend into a musical babble, their abstractions often reinforcing their power, or the malleability and complexity of communication. Wordplay is everywhere, literally, and in the polysemy of open scores’ ample choice, and in the synonymity of structures and meanings across sonic, textual, and visual mediums. Jaap Blonk directly provided directions for these scores. You can explore more at his website.

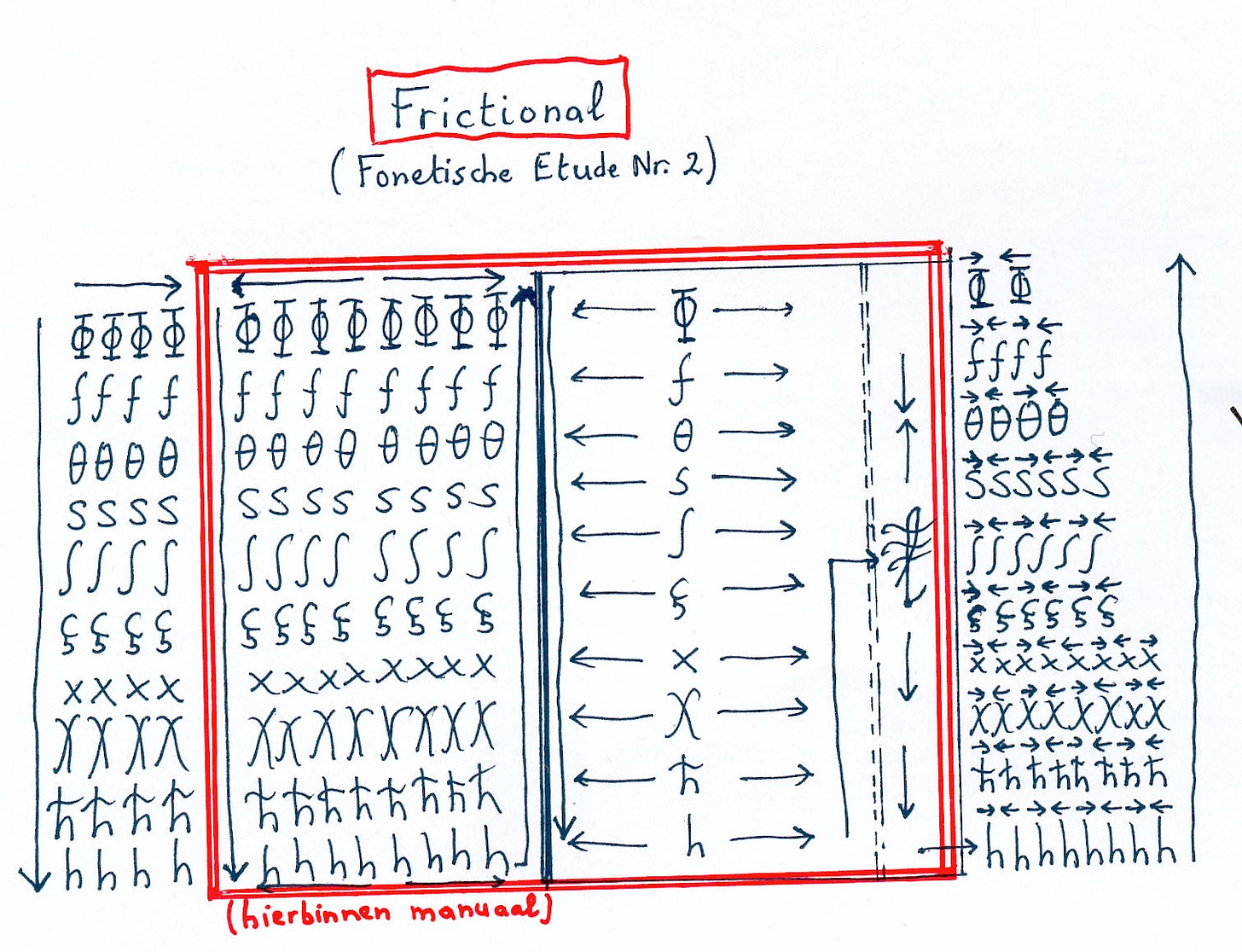

Frictional

Frictional is a 1991 composition for solo voice and undefined duration. One of a series of phonetic études, it focuses on fricatives, or the hissing sounds created by the friction of air against surfaces of the throat and mouth. International Phonetic Alphabet symbols represent where the sound occurs, from lips to glottis top to bottom. Left-right and right-left arrows indicate inhalation and exhalation respectively. The red box invites manipulations on the mouth, throat, and face for rhythmic variation. And the right-most section is a coda, read bottom to top as indicated by an arrow, where inhalation and exhalation alternate with each sound.

True to études, it is a systematic exercise. But the isolation of fricatives to inhalation or exhalation and the invitation for free manipulation of the facial vessel no doubt nudges performers to discover new possibilities at the limits of their vocalizing morphologies and to attune the nuances of their body to those of their sounds. The clash of inhalation and exhalation and shear of the bilabial-to-glottal body with the glottal-to-bilabial coda structurally echoes the friction of the sounds.

Tapwriting

Tapwriting is one of a nine-part 2015 composition cycle, Vibrant Islands, for solo vocalist with a duration of 18-45’ for the entire cycle. Performers may island-hop as they choose and revisit islands too. The shapes of their coastlines indicate their sonic character. And they contain gestural prompts and symbols from Blonk’s own International Phonetic Alphabet extensions, BLIPAX. Tapwriting in particular features percussive sounds, different islands presenting different approaches like, from left to right, hitting the cheek and skull, outward and inward plosives, inward plosives with short vowel sounds after South African click languages, and plosives prolonged into lip or throat sounds.

Like real islands in the same chain are usually geologically or structurally related, so too these islands can be bucketed in percussive structures. And like real islands beget different ecologies, cultures, and dialects in their relative isolation, so too these islands are sonically distinct from one another. Culture often reflects the land, so the similar kinds of sounds find themselves in similar coastlines, their wrench or mitten shapes warped rotations of each other through their translations. I imagine a performer’s island hopping elucidates the local differences from the larger scale. True to its name the series is visually engaging too, reminding me of something like Theodoros Stamos’ Jerusalem series.

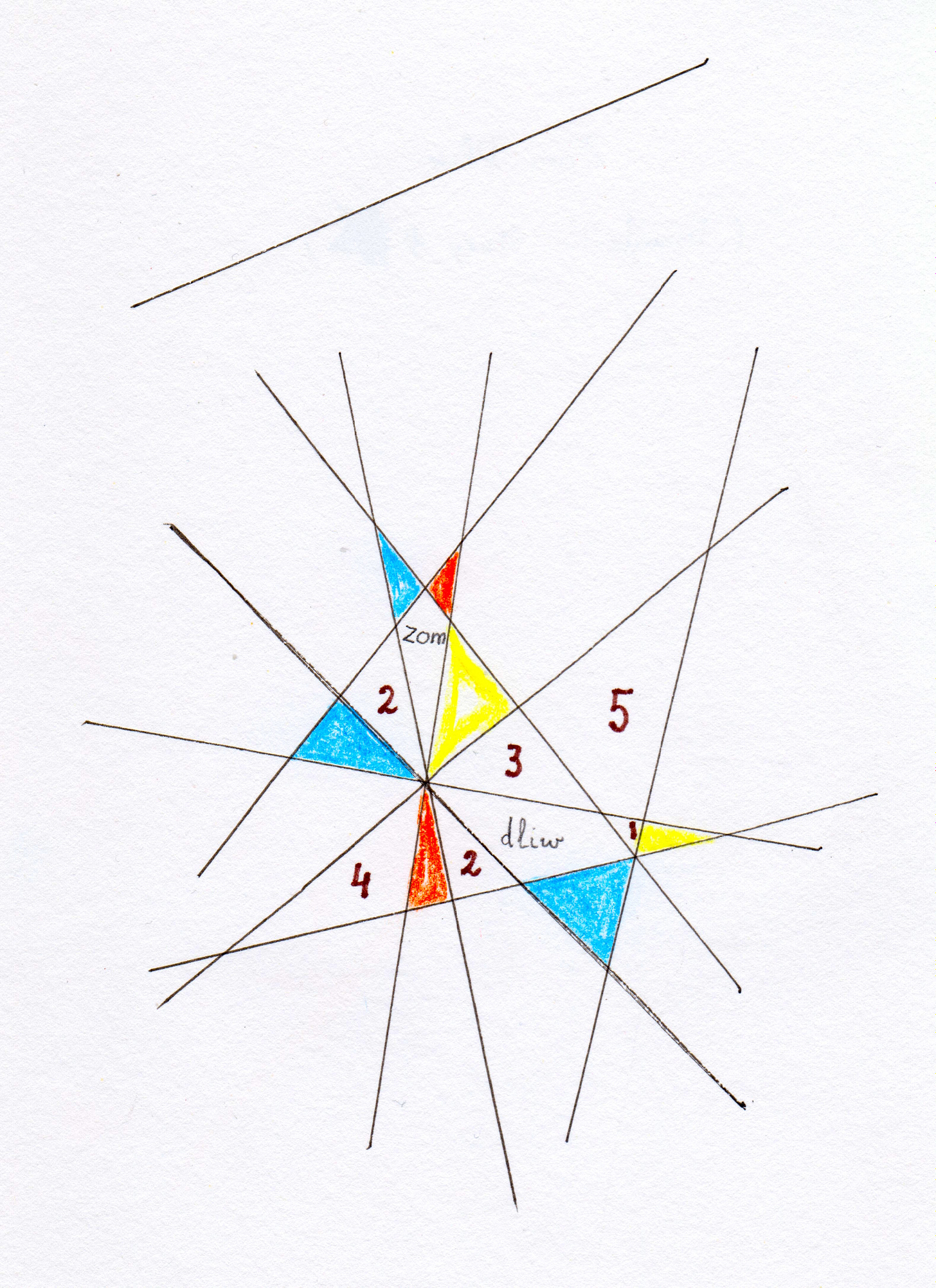

Triangle Story 23a

Triangle Stories is a series of 2016 compositions for small ensemble with open instrumentation and undefined durations. Performers choose spaces to visit, which may be revisited or visited not at all. Colored triangles are long-held sounds and colors can be interpreted as timbres, but if they are then a timbre should be associated with a color. The numbers indicate the number of syllables or other unbroken sounds to be performed there. The protagonists of the story are written in the non-triangular polygons, and they can be named or associated with a sound. Open shapes require a sound to be invented that should be faithfully reproduced each time that space is revisited. It is important to strive for a mood of storytelling.

In this and other iterations of the series, triangles can begin to appear as reflections and translations of each other, in dimensions, color, context. Performers have to keep their stories straight, remembering and reproducing sounds they’ve associated with colors or open shapes. With each performer of the small ensemble interpreting the same open score whose rules and symmetries test the memory, it can assume a kind of rashomon effect. Or maybe something like how the performance of language, in its intonation and gesture, engenders divergent interpretations from the same words.

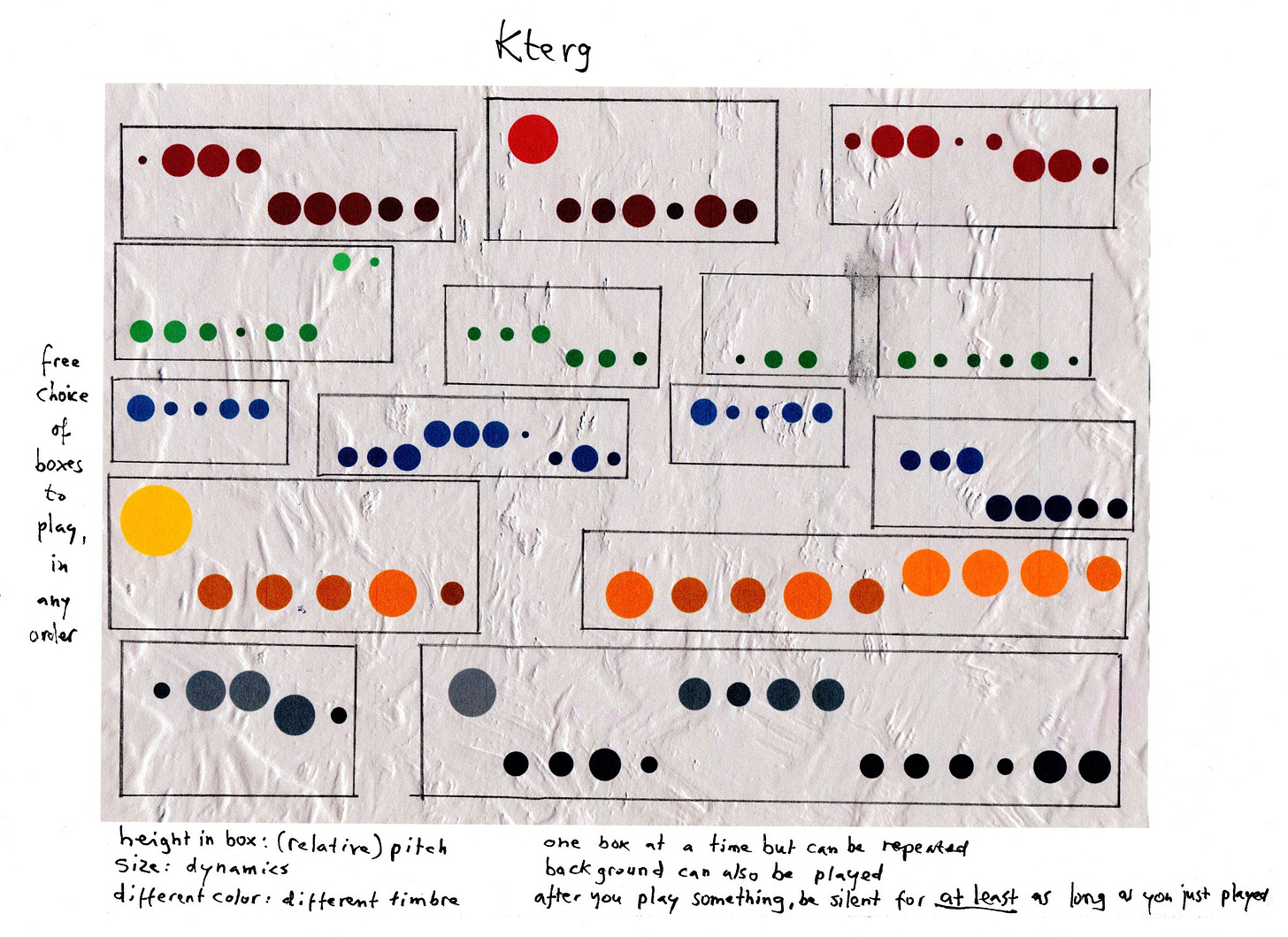

Kterg

Kterg is a 2019 composition for ensemble with open instrumentation and undefined duration. Performers may receive different arrangements of discs and boxes. It includes its instruction on the page, which provides guidance towards interpreting disc parameters within the selectable cellular structures of boxes. Discs’ height within a box as relative pitch, their relative size as dynamics, and their colors as different textures. The textured background may be played, and performers must incorporate silence for a duration greater than or equal to their interventions.

Colors’ shades are subtle, and the perception of them could be colored by their proximity to differently sized discs and similar colors. Similarly the sense of size between adjacent discs seems clear but becomes less so across a box or the page. Variable heights within the box further the blur of colors and sizes. And boxes’ offset placements can make consistency tricky across the page - a disc of the same size and color and height on the page could be interpreted as different pitches due to different heights in their respective boxes. The score’s emphasis on subtlety and relativity would seem to encourage those qualities from its performers while they navigate its open possibilities, which might require careful listening for an appropriate response to what they and perhaps others just sounded. And they are required to take ample silence to do so, though silence per sound or silence per box each both appear possible. So it assumes a conversational character. That the beige background - which, though textured here, is often associated with a matrix of silence - can be played presents some conundrums, but even someone silent is still present in the conversation, sometimes more so than those talking.

Two Abstruse Questions 1

One half of a pair, Two Abstruse Questions 1 is a 2019 composition for open instrumentation and undefined duration. It translates a question about life into tablature, standard notation, and other musical fonts with additional hand-drawn forms and colors. It comes with no direction other than that it allows for a lot of improvisation.

A kind of multilingual cryptogram whose branching lines lend a crazy wall feel and prismatic circles recall Kandinsky, whose work is perhaps inseparable from synaesthesia or the translation of air to light. Its hand-drawn forms and colors require a kind of poesy to convey, amplifying the translational aspect of playing music from the page. So like translators of text, performers might relay the character of the question more than any direct decoding. Present to a degree in a few of these scores, its funneling of textual, sonic, and visual information into potentially just sound accentuates the inadequacies of any medium alone in relating experience. And in doing so reinforces the diversity and complexity of communication, an endless font for Blonk’s work.

reviews

Pedro Chambel & Ferran Fages - Os passos seguem como um espelho (Fractal Sources, 2022)

Pedro Chambel and Ferran Fages craft three environments for turntable, electronics, alto saxophone, and voice on the 38’ Os passos seguem como um espelho.

Each theme seems to be three textures, two relatively constant, one changing, and all timbrally ambiguous. Extended techniques and electronic treatments blur sources. A pulse might come from the periodicity of a rotating surface or a beating resonance. And following the title textures appear to mimic others, a metallic chirp could also be effervescent electronics, an alternating beeping a modulating wailing, ptyalistic utterances electric sputtering or frictional turntable that itself seemed like the fetch of dewy breath along the bore. One among them drifts significantly, a resonant howl becomes stridulating static becomes dinosaur roars, an anonymous circular scraping to fan resonance, irregular rustlings to growls, groans, sucks. But though one changes more noticeably in relation to the others all are always changing. Regular soundings occurring not rhythmically but in constrained ranges of texture and time. At the thresholds of identity, texturally, through repetition, follower and followee.

- Keith Prosk

Johnny Chang & Keir GoGwilt - hope lies fallow (Another Timbre, 2022)

Johnny Chang and Keir GoGwilt play six arrangements from the medieval and Renaissance compositions of Hildegard von Bingen and Orlande de Lassus with violins, with Celeste Oram contributing voice to three tracks, on the 75’ hope lies fallow.

Violins move to unmetered spaces, intertwine and stretch time like dough. Flowery melodies might repeat in slowing velocities but more often the path towards ornamental asides feels natural, unconscious. Alternating sustained soundings buoy harmonies whose beatings bear their own time. Ethereal chorals float around instruments’ harmonic auras in resonant accord. Little material in lengthier durations drowns thinking into being. Whiplashed from these flowing sinuous curves, melodic phrases pronounce themselves plainly before these extensions begin again.

- Keith Prosk

Bryan Eubanks - for four double basses (INSUB., 2022)

Jonathan Heilbron, Mike Majkowski, Andrew Lafkas, and Koen Nutters perform Bryan Eubanks’ titular composition twice, totaling 47'.

There is something undeniably lulling, hypnotic, about the sound of four double basses quietly repeating, at slightly different tempi and pitches, an identical ‘melody’ in natural harmonics. But what is most striking here is a sense of continuously unresolved disruption: as the four ‘voices’ seem to phase in and out of sync with each other, they reframe into new configurations, retroactively exposed as illusory byproducts of hocketing overtone combinatorics; and the resultant sense of 'pseudo-tonal' harmonic motion, registering dejected resignation or even sorrow, seems always not quite right, just out of reach, as though produced accidentally by something like wind chimes. There is thus an almost circular neatness to the piece, a rather understated thematic relationship to or interrogation of the affect of ‘failure’ - the no-longer-really-four voices seem stuck repetitively trying and not-quite-succeeding to more cleanly or forcefully express a chordal sequence itself suggesting response to or acceptance of failure, and, in so failing, they of course only convey that feeling even more strongly.

- Ellie Kerry

Savvas Metaxas - Magnetic Loops II (LINE, 2022)

Savvas Metaxas arranges three reel-to-reel tape loops with some additional sounds on the 41’ Magnetic Loops II.

Pleasant melodies’ stretched spectra revel in the imperfections of their medium. Hiccuping clicks and static hiss, warped curvatures, rattles. Echoes of themselves overlap, compound and amplify modulations to change character in series. One loop appears to rearrange its inner sequence as if it were pinched and twisted into a Möbius strip, as if the end had become the beginning. What sounds like knocks on the box and synth swells blend with skips and warps. Something remains the same but it’s never static.

- Keith Prosk

Silvia Tarozzi & Deborah Walker - Canti di guerra, di lavoro e d‘amore (Unseen Worlds, 2022)

Silvia Tarozzi and Deborah Walker sing twelve Italian songs of war, work, and love with violin and cello and contributions from grandmothers Anna and Lina, Maria Grillini, and Ola Obasi Nnanna with voice and Andrea Rovacchi with mbira on the 53’ Canti di guerra, di lavoro e d‘amore.

The music often follows the text, strings support words’ melodic lines, instruments manifest narrative elements, and harmony on many fronts represents the collectivity of a community in resistance. Some of the same bowing techniques that lend a rustic roughness split sound spectra for a tactile field upon which refined harmonic work can occur that in turn allows sound to convey the complex emotions these simple songs can carry like the grief-stricken exultation of the partisan who died free amongst their mountains. Of course Tarozzi and Walker are the core of the project but bringing others together - the audible contributors double their number, the inspiration of Giovanna Marini, recording and arrangement from Mondine di Bentivoglio and Mondine di Trino Vercellese - focuses the folk of the music. Original instrumentals assume a narrative symbolism, a cloud of nervous fiddling flashed with crosscutting cello, sustained alarm whorls and wailing gliss divebombs, bowed bodies sawing and stick clicks like labor’s percussion, as other sounds might throughout, like mbira evoking falling arrows plinking. But of the many approaches portraying the oral history of Emilia, the multi-track remixes build heartening harmonies, a hair-raising emotivity in a bell choir of bicycle chimes behind a lullaby and a chorus in staggered canons exploding in number until uniting to exclaim, we want freedom.

- Keith Prosk

Martin Taxt - Second Room (Sofa, 2022)

Inga Margrete Aas, Rolf Erik Nystrøm, Laura Marie Rueslåtten, Peder Simonsen, and Martin Taxt perform three paths and one free roam in a cartographic Taxt composition with contrabass, alto saxophone, organ, tubas, synthesizer, and handbells on the 45’ Second Room.

Moving along a grid of points, staccato soundings stretched to sustain seem to illuminate the lines between them. Handbells too in their decay and its reverberant glow. Like lanterns in a chain of cave explorers. From a yawning cloud of following sounds they sometimes converge in a pitch space to together reveal the extent of it. And the corporeal vibrations of the largely low-end ensemble make the space feel real. After some time adapting to a model of a natural space, the ensemble finds a home in nuanced harmonies, everything resonating together.

- Keith Prosk

Trio Amos & Klaus Lang - Tehran Dust (Another Timbre, 2022)

Sylvie Lacroix, Klaus Lang, Michael Moser, and Krassimir Sterev perform three Lang compositions and two Lang arrangements of Renaissance compositions from Johannes Ockeghem and Pierre de la Rue with flute, organ, cello, and accordion on the 61’ Tehran Dust.

Organ and accordion’s nasal heralds sustain sounds while cello and flute’s swarm of flies unfolds for billowing laminations from all four, radiating beatings from mellifluous harmonies in “origami.” In the eponymous composition, a succession of soundings’ decay just overlay like beacons in a darkness, swelling gradations lending a miragelike tactility to the air that refracts sound like dust does light to produce stunning colors. A kind of dualism in “darkness and freedom,” harmonies bloom towards discord to recoil back to beating beauty, also alternating between a more unified choral and splits of high register howl and rumbling low. The Renaissance songs root the others, as if their flourishes were just stretched and their tremulant articulation moved from the fingers to the natural quavering of frequencies.

- Keith Prosk

Toshiya Tsunoda - Landscape and Voice (Black Truffle, 2022)

Toshiya Tsunoda arranges three environments for recordings and voice on the 25’ Landscape and Voice.

A fluid soundscape and its interplay with the living, the looming presence of air in audible silence and the swash and bubble and drip of water at its boundary, agitated by birdsong, transportation, barking, children. Glitchy events interrupt it, short cuts - like camera shutter click bursts capture movement - of the environment paired with a phoneme in repetitions from different voices in different cadences and durations and rising volume and clarity. There is a heightened sense of how fractured perception and memory of the surrounding complexity shapes a voice. “Studies” isolates sounds to click events, environments only present in cuts, as if to illustrate the enduring effects of an environment past its immediate presence. While the birdsongs that might serve as markers are replaced with others on “In the grass,” something intangible makes me suspect a location nearby “At the port” and bug sounds lend a sonic impressionism in their evening associations. It conveys the mutual coloring of everything, through time, place, and the contingent events that share them.

- Keith Prosk

UNIONBLOCK - Thetford (Lobby Art, 2022)

Jack Langdon and Weston Olencki play a long, decoupled suite with a brief interlude for mechanical tracker organ and electromagnetic banjo on the 55’ Thetford.

Instruments tend toward stranger timbres. Organ more whistle and howl or growling seismicity than anything warm. Banjo barely recognizable but for the vestiges of strings in the baffling static of industrial looms, electric tanpura, slurred rolls of ebbing thrums, and high-tension twang. Sustained for duration, they commune through a polyrhythm of pulse, club throbs, meditative waves, and stuttering phasing, finding harmony together through faith in an unseen nature. The violent “Brick Whittle” burns the acoustic space, organ stabs, scratched necks and thwacked heads on the tabletop banjo, discrete dynamics shocks that lick the walls and quickly void the air around them. TO rebuild their wholly enfolding harmonies again.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for stopping by.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $2.15 to $11.49 for May and $0.35 to $1.40 for June. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.