No Idea Festival has announced its 2022 program for September and October, including windows for streaming its video presentations. A Spanish-subtitled edition of Derek Bailey & Jeremy Marre’s On The Edge: Improvisation in Music and original works from Patrick Danse and Gustavo Nandayapa & Rhizomes Films are streaming right now. Original works from Iván Naranjo and Jim Denley will begin streaming later this month. Consider donating to No Idea if you choose to view a stream.

A new issue of Point of Departure is available, featuring: words on Wadada Leo Smith’s string quartets, Cecil Taylor’s Akisakila and its recent reflection in Pat Thomas + XT’s “Akisakila”: Attitudes of Preparation (Mountains, Ocean, Trees), and Eddie Prévost’s Bright Nowhere festival; a conversation with Gordon Grdina; excerpts from Lauren Newton’s VOCAL Adventures book; and reviews of recent Peter Brötzmann releases.

I was recently apprised of Ear | Wave | Event, a periodical of creative and critical writings around sound organized by Bill Dietz and Woody Sullender. The theme of its most recent issue is notations. The site has been added to our resource roll.

I was also recently apprised of The Light of Lost Words, an infrequent blog concerned with several media including music, most recently Christof Kurzmann on Erstwhile Records and The Tsunoda-Unami Collaborations. The blog’s music category has been added to our resource roll.

The Anthology of Recorded Music, Inc. has begun reissuing the Composers Recording, Inc. catalog digitally on bandcamp. Selections from the catalog will be reissued with newly commissioned essays and compositions to enrich the context of the original work; the first is Harry Partch: The Bewitched / Taylor Brook: Block, with an essay from Marc Sabat and a new composition from Taylor Brook.

If you’re interested in sharing a thread of thought prompted by something in our conversations, annotations, or reviews, we encourage you to leave a comment. We’re always glad to receive messages at harmonicseries21@gmail.com but if you leave a comment other readers can chime in too.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.74 to $3.93 for August and $0.65 to $1.94 for September. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Elizabeth Millar is an experimental musician, sound-artist and composer perhaps most associated with amplified clarinet and sound sculptures. Over video chat we talk about travels, handmade things, air and other materials, humans and machines, methods of organizing play, collaboration, and duration.

Some current collaborations include video integration of artificial field recordings with Allison Moore, in which sound objects might begin to be considered for their visual aesthetics, and the continuation of sharing work with a.hop. Recent releases include rare entertainment with Christof Kurzmann and AFR3. Elizabeth also runs Mystery & Wonder Records with Craig Pedersen.

Keith Prosk: Hey, how’s it going today?

Elizabeth Millar: Good, thanks, how are you?

KP: Good, good. Are you in Montreal?

EM: Yeah, Montreal. Where are you?

KP: Austin, Texas.

EM: Right, obviously.

KP: [laughs] Are things already kind of turning cold for you?

EM: Not really it’s kind of a… have you been to Montreal before?

KP: I haven’t, no.

EM: It gets really humid in the summer and today it’s one of those days where the humidity builds up until it eventually thunderstorms and we’re just waiting for that to happen to break the humidity. So, yeah, it still feels like summer. I think we’ll have a bit more of summer before things get cold.

KP: Nice. Yeah we’re still… it’s not like 100F here anymore but it’s still pretty brutal.

EM: Yeah, it gets hot in Austin, right?

KP: Yeah and we’ve got… well, Austin is a little higher off the coast, like right off our coastal escarpment, but we are still pretty close to the Gulf of Mexico so we’ve got the humidity and the heat.

EM: Oh fun. Yeah, people always say to me, oh my gosh how can you live in Montreal it gets so cold, and I’m like, yeah it also gets really hot. With the humidity it gets up to 40C sometimes. So extreme, so extreme.

KP: I understand you and Craig [Pedersen, the other half of Sound of the Mountain] traveled quite a bit together before covid, has that resumed at all or…?

EM: Yeah, we went to Australia this year but we haven’t done any other big trips. Craig’s going to France for a tour in November but we’re actually planning to relocate to Perth, Western Australia. Next year maybe, or coming up soon. I think we’re doing what lots of people are doing post-covid, making these big decisions and moving locations, so… that’s where I grew up, in Western Australia.

KP: Yeah, you’re from Perth, right?

EM: Yeah, yeah I grew up in the southwest and Perth is kind of the closest city to that area.

KP: Is Craig from there as well?

EM: Craig’s from out west, he’s from BC, British Columbia, western Canada.

KP: And is that like a cost of living decision or closer to family decision?

EM: A bit of everything, cost of living, family, climate, ease of lifestyle maybe. I mean I love Montreal, I’ve been here for fourteen years, but I think we just felt like a big change and we also have a kid now who was born last year so… he’s twenty months and, yeah, I think now that there’s three of us to consider family does start to be a bit more of a consideration, you know. And we have always gravitated in our travels to Asia, so even though we’ll be moving to a more isolated place we’ll still be close to, you know, Japan and Malaysia. Even Europe’s not that far away but Canada is far from Australia. It’s kind of the furthest you can go, which is kind of crazy.

KP: Yeah I heard that you got into instrument building or the sound sculptures through seeing - and I’m going to butcher the pronunciation - suzueri and [Junji] Hirose concerts, right?

EM: Yeah, yeah. So I was in Japan with Craig in 2017 for three months and we just saw shows four or five times a week. Completely busted our budget, went into debt just going to see all these shows, all kinds of shows, there’s so many venues and just so much going on. When I was watching these people make their sound art and their music and watching them perform I didn’t think consciously, oh this is something I need to do. But after spending time in Japan we traveled through southeast Asia and spent two weeks in Kuala Lumpur and everywhere we went we connected with other experimental musicians and we played shows as Sound of the Mountain. Then we went to Australia and we had a residency there and we just sort of stumbled across this maker’s space and we collected some small electronics and we started to use them during our residency, even though we were there as an amplified clarinet and trumpet duo. And so I think, yeah, that influence sort of subconsciously worked itself in and it was just sort of the right timing because we had this week in this empty space and we had all this extra gear and we started to use it. And also Sound of the Mountain had been on tour since we left Montreal in July, we toured across Canada, we spent three months in Japan, southeast Asia a month, so Sound of the Mountain was kind of at its peak in a way and we were ready to introduce new elements because we played so many shows together and were just pushing the boundaries of what we could do with the amplified clarinet and trumpet sounds. I wish we had gone into the studio then because it would be cool to have a proper document of where we were at with that, with that project, at that time. We have some live recordings and stuff but…

KP: The Tetuzi [Akiyama and] Toshi[maru Nakamura] recording isn’t from that time?

EM: Yeah, it is. That’s true, there is that, but we don’t have anything of just the duo. But that’s a good point, we have that one. Yeah, that was 2017 when that was recorded and then in 2018 they came to Canada and we toured that record around Canada. I think they came in 2019, yeah, just getting my [ducks in a row gesture] ‘cause we went back to Japan in 2018 but I think the recording was done in 2017.

KP: When did y’all start Mystery & Wonder?

EM: That was in 2017 also, around the same time. We had three records ready to put out and we got on the road in our van with all the merch underneath the bed and just sort of drove across and that was the beginning of the record label and then that big tour that we did.

KP: Yeah it kind of struck me as related just because Mystery & Wonder started out as a handcrafted sound object label, right, so it almost seems like a progression to go from recorded sound objects to performance sound objects with the sculptures maybe…

EM: Yeah, yeah there’s always been a sort of focus on manual handmade things and the sound sculptures are very direct and physical objects that you can see making the sound so, yeah, I think there is a connection there that’s part of the aesthetic of the label, for sure.

KP: Yeah, yeah. So I guess - and feel free at any point to take it any direction that you want - but I kind of got a sense that Craig ended up becoming not so much a fan of the sound sculpture stuff and then I know it probably makes sense in a group like a.hop to lean into the sound sculptures. But on your own or in a more general context, what are some of the decisions behind picking up the clarinet or crafting a sculpture at a given time? And maybe how do those approaches talk to each other?

EM: Going back to that residency in Perth in 2017, we were just working with a lot of amplified breath sounds and other close-mic’d sounds on the trumpet and clarinet so the use of fans was a way of automating the air and doing more things, being able to generate more than one sound, because when you’ve got the wind instrument it’s just that one sound source. And actually we were in Japan in 2017 and we saw Junji Hirose, who is a great saxophone player, but he did this performance at GOK Sound studio, where we recorded with Toshi and Tetuzi, where he had two air compressors and two microphones and he was basically pulling the trigger on the air compressor and blowing the air into the microphones and so it’s just like this avalanche of white noise. It was amazing. And he had the air compressors in another room and he just was piping the air through onto the stage. And so that was very funny because we had just been spending all this time trying to perfect blowing air through our instruments onto the microphone and he was automating it through these air compressors. So then, yeah, we got these little computer ventilation fans, we started amplifying them, and that was the connection with the amplified clarinet I guess. But then when we were back in Montreal with our friend anne-f jacques, who I know you know, we started this Piles Picnic series where we would go to outdoor spaces and do battery-powered shows and the sound objects lent themselves really well to that. Little battery-powered things that we could amplify and small amps that we used to just turn the sound into the space and it mixed with the surrounding sounds and we’d have a picnic. So I started to work with those sound objects in that way. And I always like to have my clarinet with me on stage but I don’t always pick it up. If I’m playing with someone else, I like to have it as an option, just as another avenue that I can take depending on what the other person is doing. If I’m playing solo, I often find that I bring the clarinet and I never pick it up and I’m just working with amplifying stuff on the table. But because they are kind of semi-automated objects generating sound I can create layers in ways that I couldn’t do on the clarinet. And also my mixing console is very much a part of the setup, where I can change volumes and I have three-band eq and I can mute things and I really find that’s where I control all of the layers and bring them in and out. Like this most recent release with Christof Kurzmann, that was recorded in 2019 and that was doing a lot of working with the mixing console, bringing out different layers of sound. But there is some amplified clarinet on that one as well.

KP: Nice. Yeah so just as a blind listener sometimes it’s kind of hard to tell. Particularly the fans, both fans and clarinets are dealing with air - I guess all sound is - but they’re pretty obviously channeled air. And some of the key clicks and fingering pops and frictional air notes or just the amplified air, that kind of percussion and friction of the clarinet can almost become indistinguishable from some of the sounds of the machines. Another thing too I think I saw in a different conversation that you had is that sometimes you set a machine and you come back an hour later and it’s kind of broken down. So it’s almost like some of these machines, you’d think that… I guess clarinet performance brings out human variation, but it seems like some of these machines break down more quickly than a human might fatigue. So if the textures can be similar, beyond the multiphonic possibilities how do you find yourself viewing the differences between those two systems and maybe how do you play to them?

EM: Yeah that’s really one of the core considerations, I think, of this work, with both acoustic instrument, the clarinet, and the sound objects. And I think it can really be a place that generates a lot of momentum and energy in the music because they both have these similarities, like you said, and they are unstable systems, maybe at different rates of change but they still are. But they can also be very long, like long durations of generating the same kinds of sounds and the same kinds of textures and they can be confused for each other. So the thing about the sound sculptures, I got the chance during the pandemic to work with really long durations because there was a lot of time and I would set something up and leave the room and come back like an hour later and see how this sculpture that I had built had become unstable and sort of changed, evolved, or broken down. And there were a lot of uninteresting results and a few interesting ones [laughs] Yeah, but just that conceiving of that evolution or deterioration in the sound as one sound event that takes place over 55’ for example, which is something I put out on cassette, because someone asked me to do a 55’ side of a cassette. But I’ve also played amplified clarinet for an hour or two on a radio show and it’s definitely possible to continue to play for those kinds of durations as well. But, yeah, what I like about them is that mixing of amplified sound and acoustic sound and the crossover in texture as well, and the ability to kind of layer those textures in at different times, bring some textures forward or back, to kind of create a longer progression of sound… I don’t know if that makes sense…

KP: No, yeah, for sure.

EM: The sound sculptures themselves, often it’s gravity that will throw them out so that’s where the instability is coming from because obviously the machine itself, the only instability within that is the battery, running out of battery. So sometimes I will use a low charge on a battery and as the machine slows down it will create change but also often the structures themselves are quite unstable and the whole system changes over time.

KP: Yeah so I saw a video of you and anne-f on a porch playing with sound sculptures and it does look like some found materials. Definitely unstable. Do you tend to search out materials, maybe with a sound in mind, or do you tend to accumulate materials and maybe a sounds comes later?

EM: I don’t know. I don’t really direct that collection of sound object materials, they just kind of come into my work… let me think…

KP: I guess, real quick, sorry, just to interrupt, say maybe you’re on a tour and you do want to do a sound sculpture set, have you brought most of what you’re going to use with you or do you tend to find it there and leave it when you go?

EM: I tend to bring stuff with me, yeah, like pieces of metal. A lot of what I use I’ve had for a long time and I still find new ways of making them sound and configuring them but, yeah, I guess I’m mostly concerned with their sound properties rather than their physical appearance. Sometimes I’ll see something and pick it up off the street like a piece of metal or a brush from a street sweeper. Or sometimes I just think, why don’t I empty an egg and put that over a piece of moving tissue paper… I don’t know where that’s coming from. It’s an interesting question I haven’t really thought about. And I never actively sort of seek out new things or feel I need to find new things, they just accumulate around me somehow [laughs] which isn’t great, you can see behind me I have lots of boxes of stuff but a few days ago this was very messy.

KP: Well it looks very organized right now.

EM: Yeah, it’s not going to stay that way [laughs]

KP: In my conversation with anne-f, she mentioned she very intentionally goes for less resonant materials whereas you, particularly with the fans, seem to go towards more resonant materials. I guess are there any kind of thoughts behind that, or maybe that kind of draws from growing up with the rich tone of the clarinet?

EM: Oh maybe, maybe could be. Although anne-f - maybe she doesn’t want you to know this - but she also played clarinet.

KP: Oh! OK.

EM: Way back, way back. But I think, well, at least up until quite recently anne-f was using pretty much only contact mics and she’s only recently started to use some dynamic mics in her live set to amplify, whereas I’ve always used mics, usually they’re small diaphragm condenser mics, so it’s a different requirement for the materials because she’s wanting to capture the sound through the materials and I’m capturing the sound through the air. I’m capturing the air in many cases, and with the fans I’m also capturing the sound of the mechanical mechanism within the fan and sometimes I can isolate that pitch and use that as a tone but also when I use the air coming off the fan that’s a bassy sound. And then I add other objects in on that, resonant pieces of metal or wood, or I use different surfaces like sand paper and tissue paper and wood and cardboard. So I think a lot of the reason why I’m choosing the materials I’m choosing is connected to the way I’m amplifying and capturing those sounds.

KP: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And when I think of the recordings that I’ve heard, I definitely do think of the fan and it strikes me as something that can be super resonant - it’s almost like the blades are kind of an amplifier for the motor. A lot you can do with it, at least I think I’ve heard you taking a stick or rod to it for percussion or you can attach paper to it for that crinkling sound. You mentioned you were originally drawn to it to automate air flow compared to the clarinet and that you use it for that kind of layering but are there some other reasons why fans might seem to be such a key part of what you’re doing?

EM: Well, they’re very prolific, these little DC computer ventilation fans and in any junk shop there’s lots of them. They’re easy to carry around, you can just clip a battery to them so that helps. And I also have done a little bit with motors as well and attaching tape to them to make them into propellors and using them in a similar way to fans, to just drive air onto a microphone or as some kind of activator for another surface so it’s very similar. So those two kind of DC components, they’re easy to use, they’re low voltage, and they’re very common. Other than that I think they just sort of came into my practice, in a way, and they’ve stayed.

KP: Yeah… rotational surfaces, I guess there are a lot of possibilities there, like turntables, or you can create the kind of periodicity of a wave or something…

EM: For sure. I’m often using the fans at quite high speeds compared to maybe some of the people, like anne-f will slow down the motors quite a bit, although she’s doing all kinds of things. And then a friend gave me to borrow an old medical centrifuge from like the 1930s or something which was pretty cool because it was metal and I could capture a really nice bass fan sound from both the motor and the air and it had a really nice motor controller so I could control the speed of it. But that got so fast that it was kind of scary to have the lid open and have a mic on it because it was just so fast [laughs] I did use it live a few times but it’s also very heavy to carry and once I plugged it in at a show and it blew the power on the whole block [laughs] And luckily it came back on in time for the show but it’s not the kind of thing you can tour with, it’s way too heavy. So fans are really good for that, you just pop some of them in a box and a few other objects and can take them anywhere. They also are very unassuming objects to just have with you, although sometimes a bit strange looking when customs…

KP: “Why do you have ten fans” [laughs]

EM: [laughs] Yeah I just label the box ‘hobby electronics’ and hope they don’t ask any questions, that’s my strategy.

KP: I guess the sound sculpture part of the practice as well implies a tinkering spirit, have you modified your clarinet at all or is it just a pretty normal clarinet?

EM: It’s pretty normal but, you know, I can play just the mouthpiece, the mouthpiece and the barrel, or just the first joint and I also sometimes use a funnel and a mute. So I can do some prepared clarinet and add other things to it to get different sounds. But, yeah, I haven’t done any hard modifications to it. Maybe I should get an old one and try drilling some extra holes into it or something [laughs]

KP: Yeah for that kind of stuff my mind always goes to Sergio Merce, who is a saxophonist in Buenos Aires who has attached like gas valves to the saxophone for something like multiple sustained partial fingerings.

EM: Yeah there’s lots to do and people will build these kinds of reed wind instruments from pvc and you can get attachments to get the instrument much longer and bassy sounding. I’ve never taken the clarinet in that direction and… I probably never will [laughs] who knows.

KP: I guess - it might have been your words, it might have been the words of people you were having conversations with - but I think I saw that you approached some interactions leaning towards improvisation and others maybe leaning towards a little more direction, whether that means sharing a text score or a photograph or other graphic. I think you mentioned that maybe scores are helpful for larger groups, but are there some other decisions behind choosing to lean one route or another? I know things are probably always a bit mixed.

EM: Yeah it’s always a bit mixed. So if I’m playing with regular collaborators, then both work really well because if we know each other really well it’s quite easy to get into an improvisation. I mean obviously within that term, improvisation, there’s a lot fixed because there’s already a sound world and an unspoken agreement knowing each other’s work that it’s gonna sound in a particular corner of sound art or music. So it’s improvised to a point but there’s already a large chunk that’s implicitly present before you start. So it’s nice to just improvise with regular collaborators. But also sometimes a text score can just push things a little bit further or take you in a different direction that otherwise wouldn’t have necessarily arisen, if there's like direct instructions in that text score or structural directions. And so that’s always really nice and surprising and it’s nice to take what might be a regular interaction to a different place. Then when it’s playing with people that I haven’t played with before, well, both work too because improvising just allows you to get to know what the other person is doing and to just really have fun. Not everyone wants to play a text score so if I haven’t played with a person before I probably would just improvise with them and often just have a little conversation beforehand about maybe, I’m gonna sound a little bit like this, and maybe, we’ll play about half an hour or forty five minutes, so there’s already a little bit of discussion but otherwise there’s no decisions made beforehand. And then if I’m playing solo, I don’t know, I would say both. I would do just open improvisation, working with the room and bouncing off the audience or, yeah, I probably wouldn't use a text score to play solo. Or I don’t think I’ve done that before but I’d be open to it. Sometimes I’ll have my watch and I’ll just check how long but often I just play and stop when it’s ready to stop.

KP: Yeah. Yeah yeah. So for you scores are more of a social or group thing than… you don’t really compose those fields of action for yourself? Or are you interested - I know for instance like the a.hop members, Ryoko [Akama] and anne-f sharing those text scores with each other - would you be interested in performing something like that solo?

EM: In performing, when there’s an audience, I’m open to it for sure. But generally there’s already enough going on in the space with a live audience that I don’t need or I haven’t felt the need up ‘til the present to have an extra layer of structure or definition because I can work with what’s in the space, the sound in the space, the people in the space, and that feedback. The work with a.hop is unique because we are all collaborating at a distance so we do need… well the scores themselves give us a basis on which to work and then the materials that everyone creates are edited together to produce a final sound or sound & video or sound & photo piece. Every member of a.hop contributes scores. And then in terms of the sound sculpture work, like the kind of more studio stuff, studio recordings, sometimes I conceive of the sculpture themselves almost as the compositions because they contain that inherent instability that dictates what happens to the sound. So they’re like physical constructions of composition and then I just sort of let them go and see what they produce in terms of sound and momentum and evolution of the piece, whether I decide it’s interesting in the end or not.

KP: Yeah, like the little machines, they kind of do one thing, right, so it’s not like you can direct them to do something else [laughs]

EM: Yeah, yeah, well they’re the embodiment of the eventual composition when they’re semi-autonomous. When I play live I’m constantly manipulating them, changing them, and making decisions about them. Whereas in the studio I don’t have to play that way, I can let them play themselves, they’re self-playing instruments.

KP: Yeah. I saw the score for envelopes and I guess that struck me as a little direct. Do most of your text directions tend to be direct, or do you sometimes lean a little more poetic? And I also think I saw for a residency you shared forest photographs, which strike me as a little more poetic - likewise have you gone the graphic route but maybe leaned a little more diagrammatic? How do you use the different mediums to convey ideas?

EM: Right, what are you referring to with the forest photos?

KP: I’m actually not 100% sure, I wanna say it was probably your interview with Julián Galay or something, where a residency and using some photographs, sharing those for a performance might have been mentioned.

Read Sound of the Mountain in conversation with Julián Galay here.

EM: So envelopes was a text score for a.hop and I just recently sent a.hop three more scores, one of which is a video score, one is a photo score, and one is an audio score. So a text score, yeah, you can be really direct, you can set a duration, you can set periods of sound or silence, you can specify particular sound worlds. Which can be interesting because everyone realizes the score separately and those materials can be overlaid or edited together or put sequentially and often the results are really beautiful and also surprising and that’s why we use scores, to take sound to a different place. Than if we all just improvised a recording and sent it to the person who was putting the material together. But the video, audio, and photo scores, I sent them and in this case just asked them to interpret the image or the sound through their sound art practice and I set a duration. And because the other members of a.hop all have very active practices, I envisage them making a recording using whatever it is that they’re interested in, working on at the time whilst also being somehow influenced by the visual or the audio in the score. It can either be a very obvious influence or it can be something very subconscious. They might see the video and think of a sound or a place that they want to record or they might see a photo and make some measurements on the photo and use that to program a patch that they use to generate sounds through their laptop, so it’s very open. And there’s a great trust within the… kind of a blind trust, that everyone knows what they’re doing, and it always works out. You know, it’s always amazing to work with those people, it’s quite remarkable that it’s worked so well and most of us have never met each other.

KP: Yeah, it’s pretty awesome. It’s kind of a supergroup.

EM: [laughs] Yeah, well, I mean they’re really wonderful people.

KP: A little earlier you brushed on the duration aspect and that that’s kind of been something you’ve been interested in, maybe the experience of duration. So in what ways have you played around with that, or what have you found affects the experience of duration with what you do? I don’t necessarily stand by what I wrote four or five years ago [laughs] but when I first heard no instrument machine, air the thing that struck me was how essential or distilled it was, how it was such a compact statement. And in some prep for this, I found that I wasn’t necessarily the only one who thought that, that some of the early Mystery & Wonder records were also considered so. I just think it’s interesting to go from something that seems like a kind of digest to maybe starting to work with things that are a little more naturally sprawled out.

EM: Yeah, that’s really interesting to think about. no instrument machine, air is a very compact, I think, record, album. And I made that doing quite a lot of overdubs, like that’s how I recorded it. I recorded layers and overdubs, improvising over each layer, but I didn’t use that many layers in each track, maybe three or four maximum. But the more durational stuff that I’ve been interested in is still just using one sound sculpture and recording just it and seeing what happens to it, so one texture or one set of textures and seeing how that evolves. So in a way that’s also kind of compact. It’s not going around to a whole bunch of different sounds but it’s using time and momentum and gravity as the drivers whereas the no instrument machine, air album, I was very much controlling and making decisions and bringing sounds in and out. So with the durational pieces, the structure decides, well, it’s built into the structure, the structure doesn’t decide, it’s built in but we discover it at the end, how long that sculpture generated sound. And I just like how when you have quite a repetitive textural sound that is slowly evolving, listening to it you sort of start to really notice the small details of the sound and the small variations within each cycle because often it’s a cyclic sound, like you said, with the fan or the motor. There’s that repetition but there’s also that spiraling change. It can play with our perception of time. Yeah, so in a way they are quite different, this recording, no instrument machine, air, maybe sounds a bit more dynamic ‘cause there’s hard lines and changes and it’s direct whereas the sound sculpture pieces… some of the ones on the cassette that’s called AFR3, that’s out on presses précaires, they were longer recordings and I just took excerpts and put them together. And then there’s AFR2, that’s the 55’ sound sculpture piece, they are not so much directed by me, I just chose the recordings that I liked from a larger body of durational pieces that I made mostly in 2020 but also in 2021. The challenge now is because I’m starting to play live again I got so used to being able to capture sound in the studio very cleanly and use high gain condenser mics and they don’t translate very well into a live show because of feedback issues and other things, other ambient sound in the space, if the mics are really hot they’ll pick up the sound. So that’s my latest challenge, is now taking those sounds that I got really interested in in the studio and taking them into a live setting and thinking really closely about mic placement and object placement, and how many mics and which channels and getting the gain staging really right because it’s a very different … yeah, no instrument machine, air is coming out of more of a live set, even though it was made in the studio it’s coming out of a live style of playing, and then the more recent stuff is coming out of a studio setting of no audience, just getting sounds and immediately putting them onto a medium for other people to listen to in their own spaces.

KP: Do you find that even without an audience maybe during a sound check or something and what I’m assuming is a pretty directed microphone towards the sculptures that the shape of the room affects the sounds you’re picking up?

EM: Yeah, for sure, the surfaces in the room, the floor, the size of the room. It’s really a huge consideration and sometimes there’s not enough time at soundcheck to get really comfortable so I have to be strategic about which mics I use, which objects I choose to amplify, how many different sounds I can combine at different times. And usually that gets figured out while the performance is happening and usually it’s pretty good. It often takes me in new directions as well. But it does require, particularly now because I’m using different kinds of sounds and sounds that I haven’t previously used in a live setting, it just requires a bit of figuring out beforehand, a bit of preparation. But yeah I’ve got the console, I’ve got my own mixing console, so I’m in control if something’s feeding, you just need the sound tech to set the levels and then everything else is good. I can generally contain anything that goes wild [laughs] ‘cause I like to play loud, I like these loud bass frequencies.

KP: Nice. That’s all the general directions that I had mapped out, did you want to go anywhere or have anything that you wanted to shout out?

EM: No, it’s been really interesting to talk to you, thank you so much for your discussion and questions. I don’t often have to put everything into words in this way so it often helps me to get my ideas together.

KP: Yeah, thank you so much. I think it’s always awesome to hear how people approach or think about things… I don’t know, I feel like a lot of what I ask isn’t super different person to person - it’s a little catered - but every answer is wildly different.

EM: Yeah, yeah.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

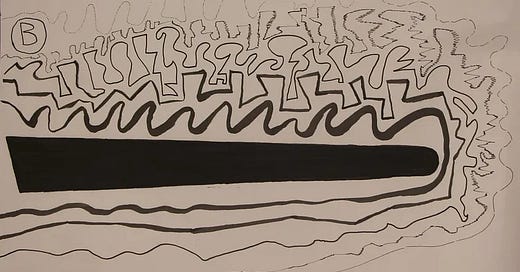

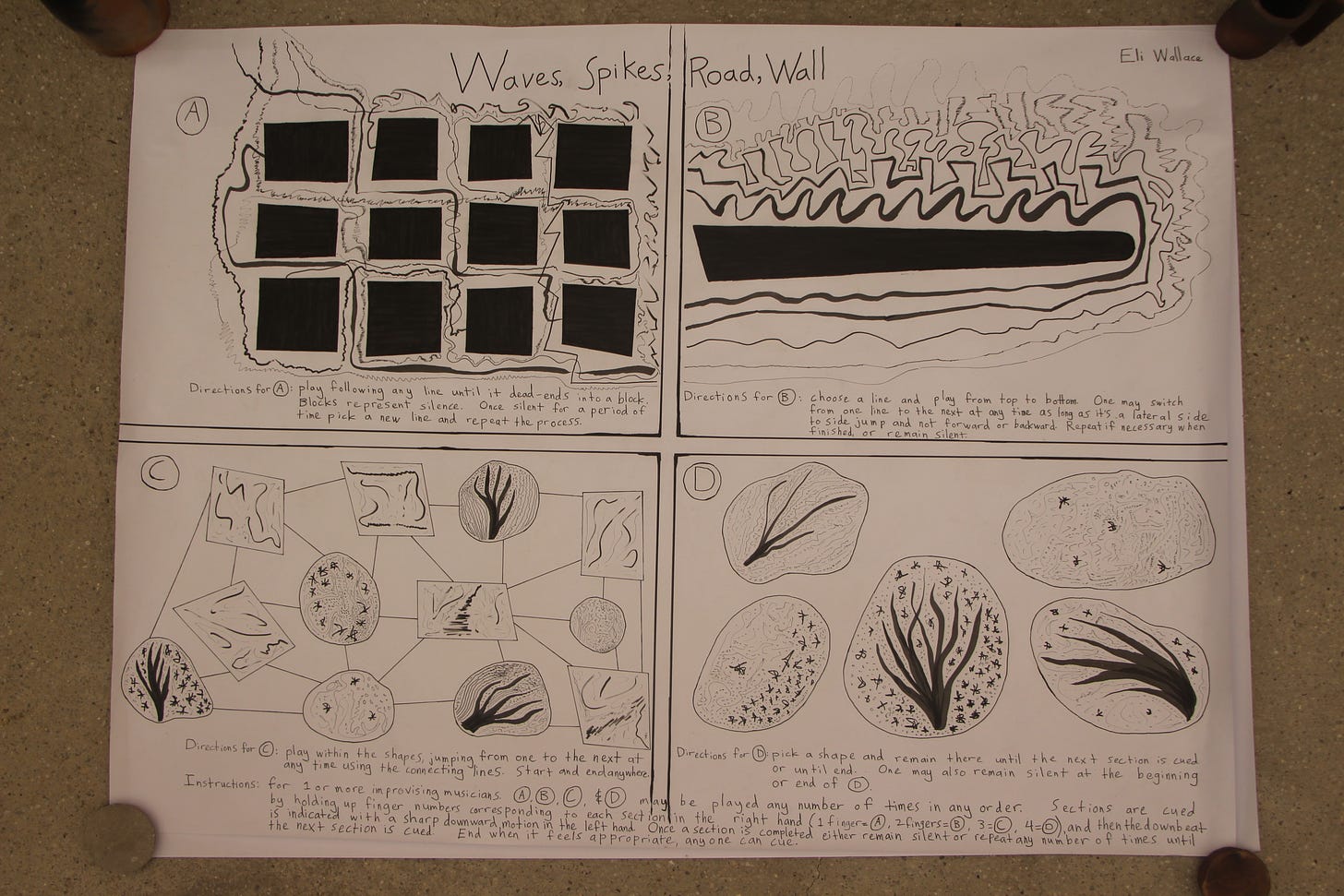

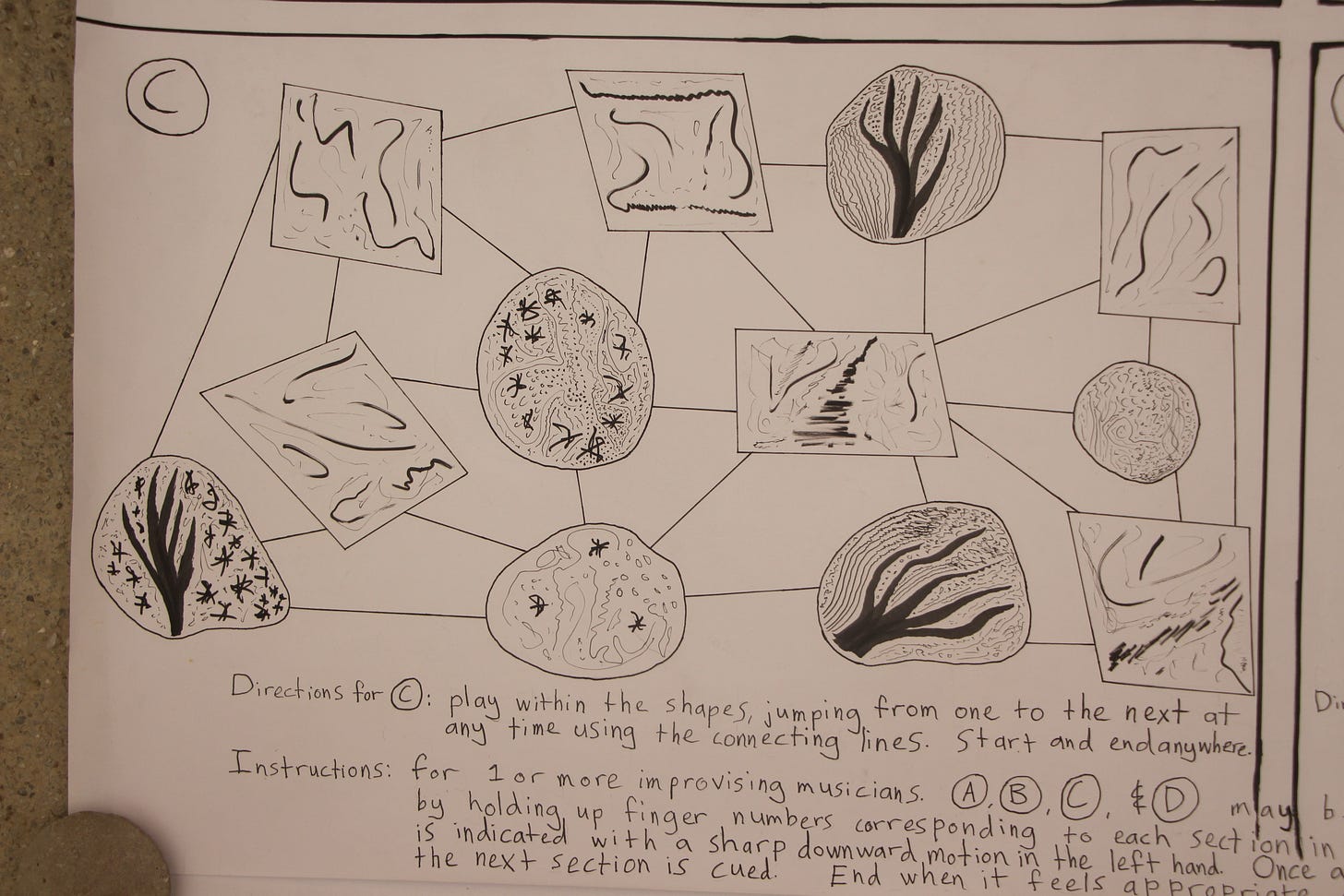

Eli Wallace - Waves, Spikes, Road, Wall (2021)

Eli Wallace is a pianist, improviser, and composer whose work might focus on the methods of sound creation, such as use of preparations and interaction between players. Some recurring collaborators include: Sean Ali, Michael Foster, and Cecilia Lopez as The Inflatable Leviathan; Jessica Ackerley and Frank Meadows as MAW; and Deric Dickens, Aaron Quinn, Karen Ng, and Nolan Tsang as Laundry Day. And recent recordings include The Inflatable Leviathan with the eponymous group, A Maneuver Within with MAW, Laundry Day II with the eponymous group, and Precepts, a realization of another graphic score from Wallace with Ali, Erica Dicker, and Lester St. Louis.

Waves, Spikes, Road, Wall is a 2021 composition for any number of performers with open instrumentation and open duration. The work was a bitácora donated to Casa Wabi during Wallace’s 2021 artist residence there to remain in their collection. It features four segments, each with their own directions, with the directions for the whole indicating that each segment can be played any number of times in any order as well as how to signal a section is about to be played, all on a single page. Two segments ask for interpretations of the shape of lines, and two for interpretations of complex forms. Directions of at least two segments, at least one of lines and one of complex forms, explicitly contain directions around silence.

I cannot shake that the complex forms look like bivalve shells or algal mats and branching bryozoa or coral fossils. While it appears possible to interpret the filled shape in (B) as sound, the relation to filled shapes’ explicit silence in (A) suggests it is also silence, and the variability of filled shapes within (A) and between (A) and (B) seems to ask performers to consider the shape of silence. Preserved ages in stone and the recognition of silence as material draws my mind towards time, and I think this composition calls for its serious consideration. The linearity of (A) and (B) surely affects a different, momentous sense of time than the vertically-stacked or spatially-dispersed structure of (C); the total structure reflects this too, which can be played linearly/alphabetically or in a varied distribution with intermittent repetitions. Graphic harmonic strategies likely induce different times too, and I imagine the crowded overlapping relationships of (A) compared to (B) will slow down the performer, as will the enlarged details of the complex forms in (D). And of course an ensemble must negotiate and navigate their individual clocks through cues.

Accompanying a consideration of time is one of space. The dispersed structures of (C) and of the total score lend this sense. As do the complex forms which seem like two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional things. But even the lines in (A) are not segregated like notes and staves on a page but intertwine and ask for their relations to each other to be considered even if the directions don’t. Spatial relationships are relative relationships and the ensemble might recognize this and its translation through them through this graphic representation, particularly when they navigate (B) in which the ensemble must think through whether top to bottom means the page or to the core of the filled shape, and whether that changes to side to side on the bend.

reviews

Cyprien Busolini / Bertrand Gauguet - MIROIR (AKOUSIS RECORDS, 2022)

Cyprien Busolini and Bertrand Gauguet play two scenarios for viola and alto saxophone on the 53’ MIROIR.

True to titles the tracks are nearly reflections of each other, with similar durations, dynamics, pacing, sounding. Sounds as tender as a whisper, drawn out long like sighs. “Oscillation” is more breathy bowing and tremulous breath for beating effects, harsher harmonics in swells of stridulations, ebbing together in dynamic waves. And “Vacillation” is all unstable, its beatings infrequent, fleeting, but palpable and the two phase through dynamics though each remains sounding in the wings as if to cultivate beatings at a moment’s notice, an axial wobble aligning for magnetic textures.

- Keith Prosk

Verónica Cerrotta - Camadas verticales (SELLO POSTAL, 2022)

Verónica Cerrotta arranges an environment from recordings on the 19’ Camadas verticales.

Quotidian moments folded for imaginary narratives, impossible cooccurrences, and arcane harmonies. A chime choir and the talking tabla of dripping water on metal. A soundwalk polyrhythm of night bug chittering and crunching gravel underfoot and what sounds like the creaking pump of an organ in a reverberant space. The wind and waves of the shore, shells sifted through hands as sand, and circular ceramics spinning on their edge over a hard surface. Shoveled gravel and swarming flies, dropped marbles percussive on different surfaces. Footfalls on old wood floors and cow crows closeby. Sounds and their sources are loud and clear, focusing attention towards their invisible relationships.

- Keith Prosk

Sarah Davachi - Two Sisters (Late Music, 2022)

Two Sisters presents nine harmonies from Sarah Davachi for keyboards, voice, strings, flutes, brass, and bell plates performed by Mattie Barbier, Mira Benjamin, Dorothy Berry, Bridget Carey, Johnny Chang, Davachi, Judith Hamann, Jessika Kenney, Rebecca Lane, Anton Lukoszevieze, Gordon MacKay, Andrew McIntosh, and Tiffany Ng.

Songs sit with a sound and shift slowly, often only modestly adding complementary elements for bold changes in texture or color. Evoke brass not just from hymnic fanfares for four trombones but the radiating waves of organ solo, compared to a nearby green that perhaps matches its color by feeling more blooming. Subtle shades for illusory fields in which sines blend with bells, voice rises relative out of hypnotic chant, and the channeled air of flute and organ blur. I wonder if the lush “Icon Studies” recall the ecstatic harmonic music of Rădulescu’s sound icon, given the context of composer as keyboardist, the contributions of Lane and Sam Dunscombe, and their spirited overtone activity. The globe-scattered collaborators and site-specificity of organ and carillon converge space and shatter time, which reamasses and flows fluid again like mercury in these colorful harmonies that convey the care and well-attuned ears in their creation.

- Keith Prosk

Violeta Garcia - FOBIA (Relative Pitch, 2022)

Violeta Garcia freely plays fifteen phobias for cello on 39’ FOBIA.

Textures reflect their titles, the insistent ticking of “EL PASO DEL TIEMPO,” the fast fiddling of “laburaHOLIc,” the growling wood of “LOBO.” Violent attacks, string flaying, and nervous pacing conjure dark moods, compounded by quick tracks’ breakneck procession. Wood and hair beat and scratched raw creak, eek, hiss under styrofoam, and scream in swings in volume. Resonant moments and purring beatings crepuscular light in an otherwise chaotic rhythmic cloud of crosshatched and stippled sound that hangs in the air with the weight of fear in obsessive compulsive percussive repetitions that both change and stay the same like the unreasonable realities of living with phobias.

- Keith Prosk

Junji Hirose / Otomo Yoshihide - DUO-1 (Ftarri, 2022)

Junji Hirose and Otomo Yoshihide play three scenarios for self-made sound instruments and turntables on the 64’ DUO-1.

Different tracks feature different self-made sound instruments, or semi-automated sounding sculptures. “First Scene” is metallic jangle, electric scratch, junk crash. Cymballic noises from rotational surfaces. Reverbed exclamations spiraling in dynamically inverse-logarithmic repetitions echoing the energy escaping the self-made sound systems. A primal resonance spun out from the periodicity of the maelstrom. “Second Scene” is machinic raspberries and vacuum suck, crackling purr an propeller percussion, electric groans and motor revs. And “Third Scene” is the grained screams of a wind-whipped mic, though the shear of still and accelerated air yet conveys a wave. The repetitions of automated mechanisms cannot escape a wave in the periodicity of their noise; despite subversions of staccato soundings turntables cannot escape the circularity at their center. Between the band of noise and waves, distilled from a diversity of discordant discarded objects, there is a sense of purity or essence in the sound.

- Keith Prosk

Austin Larkin - Violin Liquid Phases (Memory of a Past Heat, 2022)

Eight violin solos from 5’ to 15’.

Something terrifyingly elusive here in the combinations of almost-patterns/repetitions/structures not so much deliberately occluded or interrupted as ‘always already’ too-much or too-little for mechanical or mathematical regularity, or, if at all mathematical, perhaps in the spinning out of their interactions adjacent to ‘chaos’ in the ‘high degree of sensitivity to initial conditions’ sense, therefore relentlessly polyphonic across multiply-complex axes... An awareness here of the insufficiency of explanation, the dumbfounded gap between motion of fingers/hands and not-quite-architectural (because always-excessive, ‘unsound’) sonic corollary, cf., for example, the tendency, noted by Scherzinger and others, for master mbirists to cultivate finger-patterns apparently simpler than and/or irrelevant to audible result, facilitated by complexities of overtone structure and key layout... in Larkin something of this form of mystery, which is coterminous with the mystery of ‘frozen time’ or of a ‘moment’ that can be ‘stretched,’ overlaps also with a mystery like that of the shō in the gagaku ensemble, in which ‘new’ harmonic spaces can be perceived only as ratcheting up ‘tension’ which is really ‘height,’ outside of actual pitch content, a basically spiritual ascent across functionally-undifferentiated levels, emphasizing therefore only the motion itself, in other words the “ceaseless becoming” of Larkin's notes. Reductively, then, violin-as-between-mbira-and-shō, those latter two instruments not simply as decontextualized objects but rather already suggesting specific practices and understandings. Less reductively - and probably also less inaccurately, since, though “court music” appears as a point of reference in press materials for this recording, there’s nothing more specific within that field - a more firmly-grounded and indefinably ‘real’-feeling set of new ideas than I have heard in a long time.

- Ellie Kerry

Jon Lipscomb - Conscious Without Function (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

Jon Lipscomb plays six solo guitar improvisations on the 36’ Conscious Without Function.

Free association’s abrupt juxtaposition. Rapidfire fingerings and faster flourishes emit bright spidery pops in percussive polyrhythms next to shredding surf tremolo and growling metal riffage. Nervous step pattern blasts and breakneck smooth noodling glimpsing jazz and blues through an electric flood of clean tone. Harmonic twinkles in whammied fade and palmed chimes whose decay undulates. Quick repetitions that change quickly. Swiping, wobbling gestures and textures. Blustery distortions. Fluid play fitting to the flitting container of the brain.

- Keith Prosk

Maxi Mas - Maine (Ramble Records, 2022)

Maxi Mas translates three Philip Guston paintings through lute and then overlays them on the 25’ Maine.

Hear the wood. Hear the room. Warm reverberation as rich as a piano. Full body massage for a palette of viol friction. Overbowed roars that thwack the neck. Saran wrap raspberries. Accumulating chords cultivating harmonic interactions in decay in between. Like the paintings they represent, tones are abstracted through extended techniques. The overlaid lines of each painting mixed manually in movements around the mic. Their raw superposition produces a volumizing effect unlike to the flattening of most studio multitracks. And like the cover could be confused for a true Guston painting, this sound space could be confused for several lutists in the same circle at the same time.

- Keith Prosk

John McCowen - Models of Duration (Astral Spirits/Dinzu Artefacts, 2022)

John McCowen plays four contrabass clarinet solos on the 51’ Models of Duration.

Subtle structures and ascetic sustain extend the experience of digestible clock durations. Protean, shifting and static multiphonic harmonic interactions draw the ear towards microscale textural nuances like a monochrome. And similarly tracks start at the edge of the canvas, immediately beating. Smooth waves breach like lens flares of harmonic eclipse from corporeal wobbles with planetary gravity. Sines sing hymnic choruses. Motor purr and rev and helicopter whirr like the Helmholtz resonance of racing with the windows down. Deep yawps. Tectonic stridulations. Sink disposals. Death squalls. Dub hum. A journey through the contra register to the depths of low end that illuminates the vitality and violence in its heavy gravity.

- Keith Prosk

Sachiko M - I’m Here -Short Stay- (self released, 2022)

Sachiko M presents four tracks for traveling installation on the 70’ I’m Here -Short Stay-.

As pictured on the cover, four portable CD players play back Sachiko’s signature sines through four sets of headphones in different environments. Supplemental, site-specific context for the seven locations the installation stayed between 2011 and 2014 is available here. I’m unclear whether tracks are selections or arrangements but I imagine the former.

The sounds are expected for the initiated. Piercing sines, purring skips, and suck teeth glitches. Broad swaths of silence. Perhaps a mild groan from the CD player. And similar to the stability of silence and sines in previous pieces, the recorded and playback environments converge, the character of air in each embedding themselves in the other, contingent sounds of the listening environment easily inserting themselves into that of the playback, and changes in listening location and sinus and skull position changing the perception of the recorded sound. The context of an installation draws the mind towards the interaction of sounds and spaces too.

The difference is duration. Otherwise each track is structurally similar, with around 5’ of sustained sines in the 15’ and 20’ tracks, a couple more in 25’, a couple less in 10’, all distributed across three or four events, and then around a dozen instances of glitched scratch. So silence decrease a little. I think rather than listen to the four tracks as a whole the experiential effect of duration would be best experienced with some separation. Either way, even with shorter stays, the baggage of memory informs the most recent listen, just like the installation carries forward mementos of previous performances to the next. The sensation might be akin to how a holiday that lasts a week and a holiday that lasts a weekend feel when all else remains the same.

- Keith Prosk

Michiko Ogawa - Junkan (2020) (Marginal Frequency, 2022)

The 69’ Junkan (2020) presents two versions of the eponymous Michiko Ogawa composition for octet, one alongside Harmonic Space Orchestra associates Sam Dunscombe (bass clarinet), Jonathan Heilbron (double bass), Catherine Lamb (viola), Rebecca Lane (flute), Lucy Railton (cello), Fredrik Rasten (guitar), and Sarah Saviet (violin) and one with eight overlaid clarinet solos.

Harmonies begin on a bed of sonorous bass. Amass and ebb their sustained soundings cooperatively. Quickly finding quavering beating. Criss-crossing movements and waves’ tremulousness summon tension. Suspension amongst them as they all alternately buoy the harmony. Gutturally deep oms and singing celestial. Cyclical in revolving dynamics, seemingly iterative structures, and shifting harmonic constellations. Combinations for moments of euphonious elation and consonant frisson.

The second version feels similar. Structurally silences are a little longer. Texturally a saturation of odd harmonics lends a warm distortion to its glow and its overtones chirp more than sing. I originally mistook the second version for the wind trio with a synthesizer and assumed a doubling effect for octet. I might need to get my ears checked and assess any biases around performance readiness but I also think this speaks to the manifold faces of clarinet, whose character is the basis of the octet.

- Keith Prosk

Sun Yizhou & Zhu Wenbo - Responses (zappak, 2022)

When I listen to abstract improvised music like this, I often find myself wondering exactly what’s going on or what it is that I’m hearing. I’m not usually looking for an accurate answer, just one that can help me understand and appreciate the music. When I was listening to the fifth track of this album, I found that Sun Yizhou and Zhu Wenbo had come together in a nice electroacoustic harmony, I felt a sense of oneness. I wondered how they accomplished this – I saw that Zhu Wenbo had played a cassette player on this track, so I thought that perhaps he had recorded Sun Yizhou’s performance and was now playing it back alongside it. I found this to be an interesting answer that my brain came up with, because I was already aware that it couldn’t possibly be the case.

Responses wasn’t recorded live, they took turns. The recording session went like this: one of them performed a brief improvisation, and then the other one performed their own improvisation in response to that, and then the other one performed their own improvisation in response to that one, and etc. Each improvisation was about seven minutes, so one by each performer was selected and they were then layered to make each of this album’s six tracks. This duo isn’t the first to do a “blind improvisation duo” by pairing up recordings, but their response-based system pushes their sound a bit closer, but also further, from a traditional live recording.

In a live performance, the musicians usually respond to each other. A sound made by Performer A might trigger a sound in Performer B. Performers pay attention to each other’s performances so they can complement one another and co-steer the performance, it’s a non-stop conversation of gestures and responses. A blind duo can be interesting because it detaches from that – it features two performers both doing their own thing, responding to nothing, so rather than coming together as a conversation it comes together as two overlaid monologues. Responses manages to find a third perspective though, or perhaps somewhere in between. In Responses, each performer listens to their pair’s entire performance before giving theirs, allowing them to respond to the performance as a whole rather than to individual moments of it.

There is no live musical communication between performers here. There can’t be, it would be a temporal impossibility. Instead, there’s understanding in between them. The performers take their time to listen and appreciate their partner’s music while they consider their own performance and how they should respond, rather than using their partners sounds as instant musical prompts. Instead of being a conversation of sounds, it’s an interaction made from mutual understanding of each other’s personalities and aesthetic practices, and instead of live reactions, it’s thoughtful responses compressed together in time.

One important piece of information regarding this recording practice was left out though – it’s not stated in which order any of this was recorded, so the listener is unaware which performer is responding to which. The only solution that has made sense to me is to assume another impossibility – both performers are responding to each other, they’re both the second performer. In each of these tracks they come together so comfortably that I really don’t have a better guess. I think that a lot of what makes their recordings fuse so well is that that shared understanding that came from this recording project goes beyond the responses – a knowledge of their partner’s previous performance grants some clairvoyance into their next performance by offering an understanding of their way of working as well as their way of responding. In this sense, there kind of is a communication between performers like there would be in a live setting, it’s just been stretched and dissected.

On each of the six tracks, Sun Yizhou plays the no-input preamp. Even moreso than other no-input and feedback musicians, he plays with an extremely limited palette primarily consisting of pitched statics, electric bumps and line noise – but to me he feels fully in control of these sounds, like the small palette and limited options of the instrument allow him to perfectly refine his sounds. They’re splendid performances of soft noise, threatening but not aggressive. This precise style of playing also creates some uniformity between the tracks which makes the various responses interesting to compare – both because they let Zhu Wenbo try responding to similar sounds in several ways, and because they let Sun Yizhou respond to several different sounds in similar ways.

Zhu Wenbo plays a few different instruments depending on the track, including clarinet, toy piano, transducers and more, but somehow his performances never feel so different from each other. I think this is because every one, despite being performed differently, was a response to the same performer using the same instrument – on every instrument he picks up, Zhu Wenbo tries his best to channel Sun Yizhou’s no-input preamp, and it works! It’s remarkable to hear a clarinet or a snare drum so naturally sit alongside improvised electric fuzz, but every time they feel like multiple elements of the same musical system, like they really do belong together.

Responses is an album that I’ve enjoyed a little more every time I listen to it. It’s refreshing to hear two musicians understanding and appreciating each other so well, and to start their music project from that. It makes for music that contains a lot of both personalities without feeling self-indulgent. However, I wonder how much of this mutual understanding is inside my own head – can’t the human brain see any two things together and imagine them as connected? Isn’t it natural to look for coherence when none exist? Can’t it see chaos and perceive unity, or hear two overlaid recordings as one? Possibly, but none of those questions make me appreciate this music less because I do feel oneness here, and in my ears these performers come together like two peas in a pod, like a chemical reaction where two bodies are fused and a single electroacoustic spirit, held together by their mutual understanding, is formed.

- Connor Kurtz

suzueri & fumi endo - toy-piano sokubaikai / トイピアノ即売会 (zappak, 2022)

There’s something immediately surreal about this improvised piano duet, if you’d like to call it that. It has a remarkable trait of being able to simultaneously lean into and out of one’s expectations of what a piano duet should, or even could, sound like. We hear the regular pings of pianos, as keys are swiftly struck to create sounds that quickly decay as we expect them to – but the soundworld has been subtly cluttered with elements that don’t quite fit in, that confuse or disorient and create uncomfortable dissonance. These elements include: devices, motors, fumbling, toy pianos and a melodica. What’s really exciting about this, and perhaps what makes it feel so surreal to me, is that each of these elements manages to be subversive, complementary and remarkable in an entirely different way.

The devices and the motors are likely elements of suzueri’s performance. On top of playing the piano herself, suzueri creates home-made electric devices that are capable of sounding or triggering the piano on their own, whether it be by pressing the keys in a regular rate or by interacting with the instrument’s strings. The result of this, from the CD listener’s perspective, is an absolute uncertainty on which sounds are the product of machines and which are the immediate outcome of human decisions or creative urges. The mentality of the devices and the performers become interlinked, giving the live recording a string of human-machine logic which is as strange as it is exciting to follow.

The clearest evidence that these devices or that this human-machine combined logic even exists comes from the steady hum of motors. They’re already activated when the recording begins, so instead of initially standing out or indicating something musical, it feels like a natural element of the room, like it could simply be Ftarri’s AC unit. What lets this effect work particularly well is that the hum relaxes, unchanging, in the background of nearly the entire recording. The pianos are soft and sparse enough that they don’t overwhelm this hum either – how it feels is that the pianos are actually playing with the hum, that they’re following its non-rhythm and attempting to harmonize with it.

By the end of the album, the hum sounds so natural and comfortable that when the motor is suddenly deactivated it feels alarming. It feels like all of the natural sounds in a space inexplicably vanishing without you leaving that space. It feels wrong. What feels even more wrong are the next few minutes, while the pianos keys continue to be struck. My first thoughts are – how can these pianos continue to make sounds with their motors powered down? How can these performers continue playing with their machine brain switched off? Of course neither question makes sense – pianos aren’t controlled by motors and the performers aren’t androids – but it’s remarkable how this recording gets me into a headspace where I believe that that could be the case, and it’s distressing to feel the moment where the effect is proven artificial.

In contrast to the devices and motors that remove or hide some humanity from the project, but likely as a result of them, is an element that has the exact opposite effect: the sound of performers fumbling, awkwardly digging through boxes of stuff, setting up things and making alterations. It’s surprisingly prominent throughout this recording, perhaps due to the low volume level of the performance. Without visuals we can’t tell exactly what is happening, who is trying to set up what, and I can’t follow the sound to decipher what changes have been made just by listening either. But there’s something entirely natural and human about these sounds – they’re the incidental sounds of creativity and experimentation. Where otherwise the performers disappear behind the devices, it’s in this fumbling that they feel especially alive and present. Because of that, even if these occasional bumping sounds were accidental, they feel just as essential and attention-worthy as anything else here.

In addition to the two upright pianos used for this performance, smaller toy pianos were used as well. The toy pianos are primarily, or possibly exclusively, struck by suzueri’s keystroke devices, but that isn’t really something that can be felt – as I said before, rather than these different pianos and sounds feeling individual or disconnected, they all feel the result of the same human-machine logic. The toy pianos have a completely different timbre to the actual ones, they stand out from each other and always fail to harmonize. The ring of the actual pianos sound soft and sophisticated while the toy pianos feel harsh, metallic and clunky. It could make for an ugly contrast, but more than contrasting they feel more like two separate elements, one could even imagine it as two separate recordings, placed on top of each other. In this recording where performers become linked, where machine and human logic become intermixed, where instruments are literally connected to one another, it’s captivating how the upright and toy pianos still feel distinct, how they both have their own sounds and personalities – so even if it’s hard to understand this performance as a traditional duo, it can still be understood as a duo between upright and toy pianos.

One last element that feels important to me is something specific to Fumi Endo’s performance – the use of melodica. It’s one thing that stands out from the rest of the music as unique and recognizable, even feeling like it might not belong. Soft tones from the blown piano-like instrument glimmer in the background, harmonize and inflate the motor buzz and provide sparse melodic footing for the piano. It’s a live, clear, human instrument that could have been one of the most significant and affecting elements, but its played with such restraint that it’s pushed into the edge of noticeability. I like listening and being aware of this hardly used ingredient, seeing it as a controlled nuance that threatens to overthrow the logic of the entire performance, which it never does – it just sits comfortably, like a sore thumb hidden from sight.

It’s how all of these ideas and dualities come together that makes toy-piano sokubaikai such an exciting, surreal listen. None of them can easily sit together, instead these multiple threads of logic all pull at each other and make this minimalist piano improvisation into a strangely complex listening experience, one that’s difficult to judge or to understand how to appreciate. There is a surprisingly beautiful climax though – where a few piano keys are finally played in a sequence and a short but lovely melody is established. I’m not sure what I can say about it except for calling it lovely – but after 40 minutes of sporadic human- mechanical piano exploration, after hearing the piano and its performers be recontextualized by their own performance, after reconsidering the piano and how it should be enjoyed, it’s really wonderful to hear this brief, beautiful phrase that’s so easy to enjoy and finally matches my expectations of the piano, as an instrument that’s played with human hands to perform an arresting, alluring, intimate melody. It’s just really lovely.

- Connor Kurtz

Biliana Voutchkova - Joanna Mattrey - Like thoughts coming (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

Biliana Voutchkova and Joanna Mattrey freely play five environments for violin and viola arranged with field recordings on the 45’ Like thoughts coming.

Continuing what has come to characterize the DUOS2022 series, Like thoughts coming expresses an interdependent combination out of listening to each other and concomitant play. Whether focused through Aikido, Yoga, and Alexander Technique or a heightened consciousness and incorporation of sounds found around the home, both attune deeply to the current moment. Whether a fiddling rustic roughness analogous to the abrasion of stroh or daxophone or frictional textural techniques as emotive as breath can be, both markedly manifest the material of hair and wood in their communications. Unsurprisingly they blend seamlessly, moving together through sustained soundings and percussive pizzicato, quieter textures and noisy frenzies, even their voices appear to emerge from their instruments and it can be difficult to discern whether the wood is what’s groaning or if that breath is bridge bowing. To convey the comfort of finding fast friends that their excitement and intensity might not, field recordings from the garden keep a calm constant environment.

- Keith Prosk

Biliana Voutchkova - Susana Santos Silva - Bagra (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

Biliana Voutchkova and Susana Santos Silva play two improvisations for violin, trumpet, piano, voice, and objects on the 56’ Bagra.

Moments of profound resonance in activated piano reverberations, billowing breath and beating bowings but even less sonorous color combinations find a kind of harmony. Mutes and bow orientation and location change shades. Rougher textures of saliva and sawing pair. Air notes and bridge bowing both breathy. Object tapping and trumpet pops for effervescent cadences. Music box melody for glossolalia. My ear is drawn to the power of pressure on sound, in the speed of channeled air and fingers mediated through the bow. As the two move through the palettes of their different instruments, it’s their similarities that are uncanny, which in turn highlights the subtler shades of each that make them distinctive.

- Keith Prosk

Theresa Wong - Practicing Sands (fo’c’sle, 2022)

Theresa Wong performs ten songs with cello and voice on the 41’ Practicing Sands. See this 15 questions feature for more technical information.

Percussive plucked melodies less like partitioning a string than illuminating the corners of the resonator. A volumizing spatiality through harmonies that excite the body, glissandos and slides that create a gyre of doppler whirrs, knocking the body like tapping to sound the room, and the expert microphone placement conveyed in the context. Textures that could at times be confused for starlings or marimbas provide a springboard for voice in sung elegy to match the melancholy sonority of cello, or in abstract vocals to extend techniques like flutter tongue for strums. Plucking prominent enough that the bed of bowed growl in the closer sounds richer for it, from which criss cross gliss from voice and cello intertwine and the whole system appears to harmonize.

- Keith Prosk

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.74 to $3.93 for August and $0.65 to $1.94 for September. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.