The second volume of Graphème, the print publication for non-standard notation, is available, featuring scores from Christine Abdelnour, Burkhard Beins, Rhodri Davies, Clara de Asís, Emilio Gordoa, Tomás Gubbins, Hanna Hartman, Bonnie Jones, Raymond MacDonald & Jo Ganter, Montenegrofisher, Anna Pangalou, and Gino Robair

No Idea Festival continues its 2022 program of streamable video presentations. A Spanish-language subtitling of Derek Bailey & Jeremy Marre’s On The Edge: Improvisation in Music series is available through November 30 as are original audio-video works from Ernesto Montiel, Gil Sansón & Aquiles Hadjis and Bani Khoshnoudi & Christine Abdelnour through November 9. Consider donating to No Idea if you choose to view a stream.

The first Molten Plains Fest happens December 9 & 10, 2022 in Denton, TX for those nearby or available to travel, featuring Susan Alcorn, Ka Baird, Bitches Set Traps, Henna Chou, CNCPCN, Aaron and Stefan Gonzalez, Princess Haultaine III, Alma Laprida, Rob Mazurek, Christian Mirande, Monte Espina, Bill Nace, Warren Realrider, Kory Reeder, Luke Stewart, Marshall Trammell, Weasel Walter, and Andrew Weathers.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.65 to $1.94 for September and $1.31 to $6.98 for October. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Kevin Good is a composer and percussionist whose music explores silence, durations, and personal experiences. Over video chat we talk about percussion, places, people, change, and memory.

Recent releases include the field recording-based arrangements Where We Once Were I and Where We Once Were II and the percussion duos Songs for Two and Eva Maria Houben’s John Muir Trails with Katie Eikam as DesoDuo.

Kevin Good: Morning. How’s it going?

Keith Prosk: Good. How’re you?

KG: I’m good, a little tired [laughs]

KP: Yeah I saw that you - sorry I don’t know if this is creepy or not [laughs]...

KG: [laughs] …not at all.

KP: …but on Facebook I saw that you went to The Bad Plus last night, right?

KG: Yeah, it was Bad Plus and Julian Lage Trio. I was working it as my day job for LA Percussion Rentals so a bit of a late night bringing stuff back afterwards as well.

KP: Oh nice. I forget his first name but King was playing on one of your sets or kits?

KG: Yeah, Dave King. Actually he played both sets, it was pretty great.

KP: Nice. Very awesome. I think I’ve only… I don’t think I’ve ever actually listened to Bad Plus, I’ve just heard Broken Shadows, the Hemphill stuff that they did, but, yeah. Are you aware of Monday Evening Concerts in LA?

KG: I am. I kind of work for them [laughs]

KP: Oh nice.

KG: Yeah, it’s been awhile. I’m on their website still, I think. But Jonathan [Hepfer] was Katie [Eikam] and I’s percussion instructor. When we were at CalArts he was the interim person before Tim Feeney started there. So when I was doing composition with [Michael] Pisaro[-Liu] I had my lessons with Jonathan. He had us start essentially just doing tickets and interning but we’ve played with him a couple times, that kind of thing. But I couldn’t make it out to the Éliane Radigue stuff, which I’m super bummed about because it looked great.

KP: Yeah, I’m super jealous. Texas just doesn’t have… well we actually got a great Radigue concert over in Houston with Dave Dove’s organization but, yeah, Austin and San Antonio don’t really have an audience for Louis-Michel Marion and Carol Robinson and Radigue.

KG: Right [laughs] yeah I know Jonathan had been working on that for quite awhile. I think it was planned pre-pandemic and obviously it just took a lot of rescheduling and things like that but I know he’s visited Éliane Radigue at least a few times and done some interviews with her. It was a big thing he’d been wanting to get going here so I was glad he was able to finally do it.

KP: Oh nice. Well, I’ve got some stuff mapped out but at any point if you want to take it in another direction I’m happy to go there. Is there anything that you wanted to start off with?

KG: Not in particular, no. I’m happy to start and go wherever you want.

KP: Nice. So the other day I was listening to both Where We Once Were - thank you so much by the way - and the thing that stuck out to me was how the played sounds so seamlessly blended with environmental sounds. You’ve got like shimmering cymbals with waves and casino chimes with malleted bar melodies. A little diversion but some writing that I return to a bit is Sarah Hennies’ Queer Percussion and there’s a lot of obvious but really profound observations in there and one is that everything that’s not defined is defined as percussion. So in a way in my mind it sets up this thing that percussion, or an area of it, can be one of the most analogous musical sounds to what is considered natural sounds. And going the other way a lot of times people think about natural sounds as percussive, like rain or saltating sand or gravel in air or water. And then I know in slow, silent, singing you use duration and sustain to kind of blend sound and silence to where silences aren’t silences but they’re more rest or quiet. But going back to Where We Once Were after all that [laughs] this blend of played and environmental sounds, taking all that other stuff into account, strikes me as another way to engage with silence, by blending the music or what is the normative focus and non-music or background sounds. Is this recurring conscious behavior when you incorporate field recordings, or are there some other goals when you incorporate field recordings so closely into your more musical stuff?

KG: Yeah. I think it’s very conscious. I think you’re right on the money. It’s funny, I don’t remember Sarah’s writing that much, it’s been quite awhile since I looked at it, but especially her definition of percussion, as a side note, is also pretty accurate to how I think of being a percussionist. Like if percussion is all non-defined things I always think of being a percussionist as the practice of discovering practices. For me it’s always like, if something is undefined and it’s a percussion instrument by that nature that means I have to be able to translate the undefined and sometimes that means finding things that are undefined. And so maybe this is a little bit of that but I think it just means I kind of always feel a sense of being open to everything both ways, whether it’s musical or non-musical, and finding those timbral ties. So Listen, the first wandelweiser album, is probably the first tangible moment of that, which hilariously I think was actually a final project in undergrad for Matt Sargent’s logic class [laughs] not the most innovative use of logic but I think it worked out well. But the main parameters of that piece are essentially my house in Avon, Connecticut at the time, I did like a fifteen-minute field recording in each direction of the house, stitched them together, and then listened to them to find what I thought were the most naturally percussive sounds, or at least stuck out of the texture. So obviously there’s just sort of the ambient sound, leaves rustling, things like this, and then there were things… I didn’t want to remove the human element so there’s my partner at the time walking out the door and the door slamming, there’s our dog barking, the sink going on, the neighbors talking, things like that. The idea was to create a sound source or a list of these kinds of textures that stick out and to figure out beyond volume and more so timbrally what makes them stick out and then kind of recreate them. One of the elements of that is essentially you hear a couple door slams and things like that but they’re brought out of the texture further not by like turning the volume up but rather by later making a field recording specifically of me making that sound and then inserting it in. And then the third step to that process - this is all beyond the voices saying ‘listen’ in different languages, those are obviously what they are - was translating those into a more literal musical instrument and then mixing that down super low. I’m pretty confident most of the instrument things are inaudible, and sort of by design. They’re mostly on bass drum actually and they’re mixed almost inaudibly, like to a literal point. But for the leaf ruffling sound I added some textures of just rubbing my hand on the bass drum. There’s a couple of rim hits that are meant to kind of articulate the door slamming sound. So I think that’s a big part of it for me, kind of what you were saying with Sarah’s thing, that I think of everything timbrally being valid, both as percussion and just as an instrument in general, so a lot of that comes up in that regard. I think there’s a lot of, I would say, mimicking of natural sounds, you know, like rain is a percussive sound to begin with so I can emulate rain via this percussive technique or if I play crotales really softly and sporadically it can achieve a similar effect to rain. But I think what I’m more interested in is, how can I make this sound of rain continue along its extreme. Like if I were able to give rain sustain timbrally, what would that be like? Or if I could accentuate the harmonics of whatever is blowing in the wind, how would I do that? And I think especially with a lot of the Where We Once Were stuff, a lot of that is - at least in the first one with the waves and the bird sounds - a lot of that is kind of, to me, easy to extend with these closer to pure pitch and pure almost-sine tones without actually being sine tones, like all the bowed metallic instruments. Or in the example of the second one, having the piano with a little bit higher range and a little less sustain. Kind of creating this similar casinoesque sound.

KP: Yeah I guess that was piano, not mallets [laughs]

KG: Yeah I think it was altered a little bit so it was a little deceptive and I think there might be some mallets, I can’t remember. It had some at some point.

KP: On Listen I didn’t necessarily pick up the complements mixed in that you’re talking about but there was that metronomic sound that I figured was instrumental but could also have been a, you know, wiggling laundry dryer or something like that. One thing that stuck out to me there too - I don’t know if they’re phonemes or one or two parts - the kind of isolated speech, in Listen. A lot of what I think about when I think about words is the cadence of them and usually that’s established along a sentence or something like that but isolating little phonemes is kind of like a single hit.

KG: Yeah that’s a good point. I didn’t think of it that way consciously but I totally agree. I think it’s super interesting when you take just the single word or phonemes out of context.

KP: Yeah. So I guess if field recordings can be so close to percussion, is there something that makes field recordings not percussion?

KG: Oh man…

KP: One thing that comes to mind is, does it make a difference whether it’s played or passive?

KG: You mean the field recording itself?

KP: Yeah, does it make a difference whether a sound is played or made by something that wasn’t necessarily intending to play?

KG: Not really, for me at least. And I think so far, with these pieces, I think a lot of the excitement is… OK, if field recording is not percussion for me, then it is transcription for me. Because I think a lot of the fun is defining parameters of what I’m trying to get a recording of and for what reason. For example in the second Where We Once Were, when I recorded a bunch of casino stuff, obviously the goal here was to get human sounds. So people talking, not a disturbance of the environment or anything like that, it’s preferred. I think I had struggled with that piece for awhile. I had many, many iterations of that particular one. And by that I mostly just mean a piece that uses a lot of field recordings I had made from casinos in Vegas. And I think a lot of the issue was what I wanted to add to that, if anything. This is kind of a joke actually that Matt has said to me in that class I did Listen, he mentioned it must be hard for me to do electronic music because I think everything I do is starting with something whole and then reducing it as much as I can, or at least as much as I’m interested in, and electronic-based composition, even if it’s just field recording, is naturally an additive process. And he’s right, that is a big thing for me. With those field recordings it was really hard to decide if I needed anything other than the sounds of the casino. And so initially the main thing I wanted to do… essentially all the Where We Once Were are places that I have some form of nostalgic tie to. So the first one is mostly field recorded in Hawaii, which is where my mom is from and where I was born, and then Vegas is where I was raised. So a little bit of site-specific nostalgia was playing into that. And the main contrast I wanted to have with Vegas is the inescapability of all the casino sounds and how repetitive and normalized they are to someone who spends time there and Red Rock Canyon, the state park there, because it’s incredible, I spent a bunch of time hiking there as a kid and an adult and I’ve used those for these pieces I call trails which are essentially I go for a hike and I’ll write a short melody based kind of on the hike. A lot of the times it will have some sort of marker in terms of… there’s nothing really set or defined but a lot of the times the weaving of the melody will be reflective or if it’s a loop sometimes the melody will be written in a way where it’s a repetitious loop. Things like this. And so the thing that was really tricky for a long time was that I wanted to just have a field recording of the casinos and the field recording of being out in Red Rock. The issue being, part of the greatness of Red Rock is that it’s nothing. You can go like twenty minutes away from these inescapable slot machine sounds and music pumping through everything to pretty much silence. And it’s far enough away that you really can’t hear the highways or anything like that but it’s also a desert so at least in an audible level there’s not that much wildlife going on, there’s a couple birds here or there but it’s pretty much stillness. And I think that is really great when you’re there but that’s really hard to evoke through a field recording because it’s not necessarily defining of the place as much as the absence of sound. The piano sample is from a recording of a piece called Three Casinos in Las Vegas and I used a lot of really basic harmonic things in high registers, really fast, essentially emulating slot machine sounds. There’s kind of a question to me of, do those actually relate in the way I want them to, and I think - obviously since I put them in there - the answer is yes. But I think both of those things happened separately, meaning one is just the pure sound - and this is much more defined in the first piece, which I think extends the natural sounds via these bowed instruments - this process is much more of, these field recordings exist and can exist on their own and then this other piece that kind of happened separately is a non-committal transcription of those and just by the nature of being a transcription overlaid and put next to them, I think, works. But in that case it’s almost like the field recordings could have been left alone. I just think trying to contrast that desert part, it doesn’t come across unless you’re there.

KP: So you talked a bit about isolating things and how that’s kind of a goal, whether that’s the harmonics blowing in the wind or particular things out of a field recording. One thing that I felt is that the way you isolate things still maintains a sense of place. Kind of like a fossil can tell someone a lot about the kind of environment it was deposited in, a particular type of bird or casino chime is gonna tell people exactly what kind of environment they’re in. But are there any ethical considerations that you navigate as you isolate things? And I know this is more art than science, but do you feel that there are dangers in isolating things from their entourage of associated sounds… but if you do want it to be on the table, questions about recording voices without consent and stuff like that too.

KG: That’s a good question. So there's a couple thoughts with that. I think the for isolating in particular I do all of my field recordings with just a zoom recorder that I sit with… though I was making the third Where We Once Were and it got stolen [laughs]

KP: Oh no. In a park?

KG: Yeah it was basically in a bush.

KP: What! Who steals things in a park?

KG: Yeah, I was pretty surprised about it. I super didn’t expect it. I think I had joked to Katie right beforehand like, if it happens it’s part of the cost, whatever and then it happened and then I was like, I wish I was not so casual about it being part of the cost I just didn’t think it would happen [laughs] It’s certainly something I wouldn’t say I grapple with but I do think about how things are and how I’m going to affect the environment. And so for me it’s like, in the case of the first Where We Once Were, a lot of that isolating idea and finding these sounds is done as inconspicuously or non-disruptively as possible. Like that piece’s recordings are all from two places, one is just a beach in Hawaii on Maui - I forget which beach - and rather than trying to run in and record the waves and stuff there’s a spot where the waves break on the rocks really loudly and really nicely and it was a super thundery rainstorm kind of day. And so there’s that and then actually the area Katie’s dad lives in, in Maui, who we were staying with, has a lot of birdlife and wildlife in general. I wanted to get recordings of that without entering the environment more than it has been so I just put a zoom on his porch and grabbed from there. Any of the isolated sounds, I think that mostly happens in Listen and I think my… I don’t think I’ve really hit the isolating of a sound so much so that I’ve consciously thought about it being disruptive. More so that I have to think about it, meaning for the starting process I try to begin in a place where I’m getting an overall effect. And I think if I do something, even like in Listen, recreating the bass drum sounds, I don’t tend to do those in the environment. I think when I was nineteen or twenty I did a snare drum piece in Red Rock Canyon that was really loud and I wanted to hear the bounce of the canyons… that felt really weird, I very much wish I didn’t…

KP: [laughs] Am I the asshole?

KG: Yeah [laughs] it was like I really wish I didn’t do that, that feels weird. So I've kind of just stayed away from that kind of stuff. But more on the ethics of recording people and consent and things like that, I haven’t found a good solution, but it is something I think about a lot. Because obviously if I'm just walking around the casino with a recorder, I'm not going up to every single person and getting their permission and asking them what’s going on but I'm also not invasively going up to someone and showing the zoom in their face [laughs] but it is a weird thing and we don’t have to necessarily go here but I had mentioned the piece, The Chords In My Life.

KP: Oh, we’ll go there.

KG: Cool [laughs] it’s a really cool piece. I really like it in terms of its concept which I honestly don’t remember how I Came up with it but it’s maybe a lack of harmonic fundamentals being an interest to me… but I came up with this idea of each person I meet I create a small chord for. It can be separated hands, it can be any range, whatever, but it’s meant to be reflective of that person, obviously not defining, you can’t define a person with a single chord, but something that evokes them or makes me think of them. And so the only parameters - it’s kind of intuitive based - but the only real parameters are if I think of people together, like if they’re two friends I met at the same time or we’re all in a book club together or something like that, then there might be some kind of common tone or idea between us. A lot of times people that are related, like my family, pretty much all have the same chord voiced differently. There’s lots of things like this. If they’re people I met playing music and there’s a particular piece we were playing together when we met that kind of plays into it a lot of the times. Like Richard [An], the pianist that played in Quartet Friends with Katie and I, we all met playing [Luciano] Berio’s Linea so that C# and E that starts the piece is in both of their chords. I kind of define whether or not someone should have a chord as if they've made an impact on me and if we’ve had a meaningful conversation. Again it’s super intuitive but if I consider them someone that has even in a very small way made an impact on me, though obviously enough to remember their name, then I might consider giving them a chord. Which I think gets really complicated because a lot of times they’re people I'll meet and it will be a day where we've had a nice conversion, maybe I met them in a coffee shop, blah blah blah but we don’t exchange information, and then I want to make a chord, and then it becomes this whole thing for me like, would they care, would they mind, am I being intrusive. And it’s never happened but there is also the idea of if someone doesn’t want a chord certainly they should have the option to not be included. I kind of set a rule to not alter them which was intended to be a good thing so I'm not doing any revision of people that would maybe make it seem like I'm changing my view of them.

KP: Yeah. First impressions.

KG: Yeah, exactly. The only change that really occurs is if someone passes away I will change the noteheads to be diamond-shaped as a way of indicating that. Obviously I started this not when I was born so there are a lot of people that passed but made a huge impact on me when I started this piece, friends and family, so I wanted to have a way of denoting them as well. Oh and then a lot of the times with these chords, I've never really had a way that I'm happy with as a performance of them, especially as they’re always growing. So I just keep them as… I think I have one around here somewhere…

KP: Just like laminated cards?

KG: Yeah. But for me it gets complicated in terms of whether or not to talk to people about them and whether or not they want them and what they are. I mean, there's not really a performance of them frankly. I tend to give them or give a copy to people if they want it. Or if they’re musicians a lot of the times I've had people ask for their chord and then do an improv or some kind of realization of the chord. I know Erik Carlson did one for one of his home concerts. Beyond that they’re often used as source material in pieces. A lot of the times if I'm writing a piece for Quartet Friends, for example, I'll use some material, though varying it, from Katie’s, Richard’s, and Wells [Leng’s] chords as kind of our harmonic basis. Just a way of incorporating them almost as a source material for our harmonic language. But I think the closest I've ever had to really rethinking things about it is my friend Justin was talking to me about it and I was like, yeah so I made your chord, and we had been playing in a bunch of ensembles when we were at CalArts together and I play in his large improv group and he just said a very simple sentence of like, how come if we’re musicians you don’t ask us what we want our chords to be. Even that I just had not thought of. His whole thing was like, well I could just tell you what my favorite chord is.

KP: Well, sometimes the way people perceive themselves is not how they are perceived, yeah?

KG: Exactly, yeah. I was gonna say, and I think that was kind of my immediate answer, is that I think of the chords as my perception and my first impression of you, not necessarily as yourself. And it’s also musically not necessarily your favorite chord. Just because you have the ability to know a chord doesn’t mean it would be your favorite kind of thing. But it did really make me think like I wonder what people think and how much I should factor in the consent and ethics of how people feel about having a chord in general and also what their chord is. Like I know my mom would not care, both of my parents are not very musically inclined and especially on the experimental side, so I know I've shown her her chord and she was very supportive but also like, cool I don’t know sounds weird. There is part of me that’s like even something as simple as if a person is upset that their chord is dissonant or if that is enough of a deterrent that they don’t want a chord, how do I deal with that? On the other hand, if I’m thinking of it as a standard piece of music and someone tells me I don’t really like this chord ‘cause it’s dissonant then I'm like, OK well I don’t know how much I'm gonna factor that in. But obviously it’s much more than that because it is reflective of that person. I don’t really have a good way of dealing with it except I've tried to have more of a conversation with people. And I don’t really do anything that public with them, if that makes sense. They exist in pieces and typically I will talk to the people involved if they want to know where their chords are in pieces or I'll tell them like, hey I wrote this piece for us it uses your chord, that kind of thing. And when I make a chord for someone I'll try to talk to them as much as I can. It’s hard when it’s a person I don’t have any contact with or that kind of thing - so I will try usually to the best of my ability to mention it to them. As I said it’s never happened where someone’s been like, I don't really want a chord and I don’t want to be involved in this, but if it did happen I would totally be fine not including them. Which is kind of weird.

KP: Yeah that seems like a strange point of contention. It's not like you’re writing diss tracks. And dedications happen all the time. I doubt Ken Vandermark or Anthony Braxton are asking like, hey can I put your name as a dedication. It's a gift and you can take it or leave it.

KG: Yeah, exactly. That’s a good way of looking at it.

KP: So there are no directions attached to them beyond the pitch information, right?

KG: Yeah, exactly. It’s just that and then the diamondheads indicating if a person has passed. Other than that it’s just a single chord on a page.

KP: And you mentioned some contextual information, like if y’all met while performing a piece together you might pull a reference from that, but is there something in pitch that might remind you of someone, whether that’s harmonic interaction behaviors or, and I know instruments aren’t specified, but maybe like the color of a chord or something like that?

KG: Yes, a lot of that thing, a lot of those kinds of parameters exist. For example, string players, a lot of their chords will be based on one or more of the open strings of whatever string instrument they play as kind of like the pedal tone or fundamental lowest root note, that idea comes up a lot. And there are certain things that are harmonically tied and linked, it’s not super set in stone. Like I know my family has a lot of fifths - I think in general there’s a lot of fifths - but overtly I use a lot of fifths… I'm trying to remember, there’s a couple chords I don’t have memorized, most of them actually, but I think my mom’s is based on A and E and then my dad’s is an octave lower, something to that effect. But something usually intervallically. With family it’s fifths, for me fifths and fourths are just that warm, nice, comfort, home kind of feeling. And that is similar to Where We Once Were, like a nostalgic and restful place. I think using that to describe my parents is accurate, it makes a lot of sense. They’re a good example because, starting with them and that fifth and knowing that I want to keep relations as much as possible, that fifth kind of permeates throughout my family. And so you can hear common ideas like that that exist beyond that point. And another interesting thing that I'm sure has happened but I haven't really thought of is I think I’m in the five-hundreds right now and so there are enough chords, and it is hard for me to not view them because I obviously know all of the relations between everyone or how one person might know another person or how these people have never met kind of things, so it’s always really weird and interesting to me in that I'm sure there’s a good chance I have unintentionally had some defining characteristic that people might then think… like, if they looked at all of them, that fifth probably shows up in the exact same way with someone that has nothing to do with my family. So there is a bit of an interest in that happening naturally. I am not consciously going back and trying to pinpoint and make sure none of that happens. I've kind of set a few rules for myself that prevent me from unintentionally making the exact same chord as someone else, for now.

KP: Almost as much memory related as it’s music related, yeah? Actually while you were talking about field recordings I kind of thought about isolating things from their entourage is almost like memory anyways, right. You just have a few flashbulbs and smooth things between those flashbulb points and sometimes they align with the truth and sometimes they don’t. So you talked a bit about the interconnectedness or the interdependency of the people in your life with the chords in your life as well as that interdependency of sounds in field recordings, which is kind of ecological. And then in your presentation of things, everything is handmade, everything appears - not to be meant as an insult - with an almost childlike simplicity, which to me has connotations of a sustainability, like living simply, and of course there’s the field recordings, sometimes of very natural places, so do you view your music as a kind of environmental music?

KG: Yeah, I think so. I would say more than anything else that could be… well I don’t want to necessarily say it, that ‘environmental’ has to be a political stance though maybe it does now, but I think it’s the most conscious idea outside of… lemme rephrase… it’s probably the most conscious issue or problem that I try to address and I think I do it from a stance of just observing different environments, it’s that kind of idea. I certainly don’t take the childlike idea as a negative, I think it’s dead on the money. That’s partially why the Songs for Two CD is totally written with a crayon [laughs] it is obviously conscious. But I think for me a lot of it is a process that is reflective of how I view the environment of being a watchful observer and trying to keep a focus on these things. And I think a lot of it is also just what’s good for my mental health, meaning for me I think as a composer I like reducing things as much as possible. Maybe not every time I'm trying to reduce it to the smallest thing but as far as I think the piece can go I would rather just pull back as much as possible. And I think as a result there’s a lot of my practice that’s built more into the idea of sitting with something and really engaging with it almost where it’s more about the sitting time that creates the space to observe. So a lot of writing everything by hand and handmaking things is part of that. It’s partially that it’s just a task that is really valuable to me in terms of just being able to sit, whether outside or on a hike or inside listening to some music while drawing some lines to eventually be staffs, that feels really good to me. I think Songs for Two is a great example of when I really felt like I captured that feeling because the “Together” piece in that is just literally a fifth and I think I would feel weird for so many reasons, just putting a fifth infinitely and calling it a day [laughs] I think part of that is because I want it to feel non-intrusive and kind of natural. And so I think a lot of that is… I wouldn’t say I'm anti-technology or anything because I'm not, but I think a lot of nice things can really get lost just forgetting about them. For me, finding this practice of writing by hand, which is certainly not what I always did, but at some point I just felt better about all of the material I wrote by hand. I think it’s just a reflection of that process that lets me sit and think about what I'm doing and how much I really wanna commit to each piece and each note. I think a lot of that is for me processes that also exist in the environment. I think the trails piece is a pretty good version of that to where, yeah, it’s very easy that I could have just written these melodies based on trails and also not hiked them or I could just write little melodies as a book but for me the act of engaging in the environment and engaging in the trail both as a mental health practice for myself and also just to be conscious and aware of how things have changed is important to me. That’s why I think it’s clear on a couple of the trails melodies …I'll have to go back but I think at least a few of them I've done multiple times so I've specified the trail name and the date I hiked it and in some ways they are almost a melodic version of the Chords In My Life. And along that line of thinking, that one has conscious change. Where the chords I'm sticking with, not altering it because it’s a person, the trail I want to emphasize if it’s changed in some way. Which does happen. The trail by my house is severely different, where it used to be super green and lovely and now is mostly burnt from wildfires and things like this. I think for me it’s more of, I might not necessarily be saying anything in any direction about the environment so much as observing that it exists and encouraging others to also make this observation and consciously find a way to deal with that.

KP: Yeah. You mentioned forgetting and just going back to the memory thing, writing things down or being there, walking something it makes it not just a cognitive thing but a kinetic thing and activates that part of the memory as well, definitely a good reinforcement. So a lot of the kind of percussive materials that you use, I feel like they’re almost always metal, whether it’s glockenspiel or vibraphone, cymbals, and a lot of the time that is pitched material. So with all the percussive materials available to you, including field recordings, what draws you particularly to resonant metals and pitch?

KG: That’s a good question…

KP: ‘Cause usually when people think of percussion… probably classical percussionists first think of pitched percussion… but for people that grew up on rock, they probably don’t so much think of pitch with percussion first.

KG: There’s a couple things that immediately come to mind. The first is it’s an interesting point that you brought up that I hadn't thought of in this particular context because I was just thinking of someone like John Luther Adams who obviously does a lot of environmentally-based work in terms of compositionally having that part of his process and practice and also being heavily involved in percussion in that he kind of does the opposite, they’re all really big drum pieces, thinking of like Inuksuit and these kinds of things. But I think I have some of that that hasn’t been performed that are really drum-based things and non-pitched percussion but I think a lot of the times for me those feel… there’s probably something there to growing up playing rock drum sets before becoming a classical percussionist and mostly doing that by myself but the drums to me don’t reflect a lot of the natural world that I'm interested in on a timbral level. They feel less like an extension of the environmental sounds and more like evoking environmental sounds. I wrote this piece while I was at CalArts called The Culture of Sound which I haven't really stood by as a piece but the idea that I did really like in it was thinking of color theory, being each color contains a certain amount of each other color and its just this kind of meshing. That piece was intended to explore everything in that same kind of theory but as like a timbral theory…

KP: Sorry to interrupt but are you a Catherine Lamb fan?

KG: Yes.

KP: Her kind of riff off of [Josef] Albers’ Interaction of Color?

KG: Yeah, yeah I know a little bit of that, probably should know more but yeah. That piece, it was specifically because I was dealing with the fact that I have a lot of non-western percussion playing that I’ve done growing up and going through school. So I’ve done a lot of West African, Ghanian drumming and studied in Ghana for three weeks and done some Middle Eastern drumming and these kinds of things and it’s always felt super separate from everything else. So there was this idea for awhile of like, well there’s like gyil or balafon that are basically xylophones and vice versa, they are literally constructed in the same way, they are wooden bars that are assigned to a pitch, why is this one being used over this one and do they relate. And then that expanded into the idea of every instrument having some kind of timbral relation to one another and I think some of that still holds true for me. So for me I think a lot of the pitched material makes it easier to think of this timbral quality between things as an extension, whereas a lot of the non-pitched or even wooden instruments like marimba and xylophone feel more difficult to deal with as an extension of either environment or other timbres. It’s not necessarily that I’m less interested in that it’s more, to put it in a very simplistic way… if I think of everything as like a big spectrum of sound to me there’s a certain point where it’s standard low G whatever bowed note and then that can extend to the metal wire of a string that eventually starts to sound like a mallet instrument and you can exploit how similar those two sound to each other via using the same implement, such as a bow, and then extending up past that both in range and in timbre would be like glockenspiel and then crotales after that. And then extending beyond those things to me, kind of in a way cyclically wrapping around into noise, we create like non-pitched resonant metals, to me those are the next step in that band, so that’s when we enter cymbals and triangles territory and that bands back to noise which then backs into drums and things like this and then wraps around itself. And so I think I have a tendency, if I’m trying to do something environmentally or do something that is more field recording based or these kinds of ideas, I tend to lean on that band more. Whereas if I’m using the non-pitched percussion a lot of the times I’m using it as its own thing, like a solo piece or something like that because I’m not necessarily placing it next to a sound that already exists. Or, I like that they sustain [laughs]

KP: Yeah that can be a powerful tool. So you mentioned… did you say Arabic drumming? I know you said West African.

KG: Yeah, I’ve done a little bit of Arabic drumming, Middle Eastern drumming in general. I haven't done any Persian drumming but a lot of frame drum kind of ideas and Egyptian riq, that kind of stuff.

KP: Nice. I’m not as familiar with the North African, Arabian Peninsula stuff but in a lot of West African cultures there’s no boundary between the performers and the audience, right? So the audience kind of comes in and they can drum. And I imagine when you’re performing this music maybe it was in a western setting so that boundary was there… and of course whenever you’re field recording you’re embedding yourself in the environment so maybe everything’s all together. I guess, do you find that that kind of dissolution of boundaries that you might’ve been exposed to as you grew up plays into your music, as far as performances?

KG: Yeah so I think it’s kind of a question of community for me. Because you're right in terms of a lot of that drumming, especially when I was in Ghana everyone knows how to do everything at least to some extent. Anyone who’s like five can just walk up and start to play an accompaniment pattern that they know and one it’s totally cool and two they totally know it. But that’s built into the community and the use and idea of the music. I’ve done also a lot of performed versions in a western setting where it’s not that, it’s the ensemble on a stage and everyone watching. I actually went to CalArts at a very unique time for their African program because with the two different teaching schools they had transitioning, one was more of the making it western and having that boundary exist and the other group didn’t want that and so there was a conscious dismantling of that barrier. There was a lot of having a couple people that they knew that were from Ghana or people that were private students before going to CalArts, they would try to break that barrier and invite people in. So dealing with the conscious setting of the barrier between me and the audience with like the western classical and contemporary style of performance, that certainly is a thing that exists for me and I’m trying to think… I feel like I have something I’ve done in the past that invites the audience in, maybe I haven’t. But I like the idea of engaging the audience in a communal way and when I was in undergrad my primary teacher was David McBride and he is really big on this idea. He has a bunch of pieces that involve audience participation. He has a whole piece that the percussion ensemble did the year before I got there called Percussion Park and they’re each pieces that are short percussion pieces based on activities you would do in the park. So there’s “Swinging in the Park” and it has all these broken triplet rhythms, ideas like that. There’s “Talking in the Park” which is like a lion’s roar and cuica conversation duet. But then there’s also pieces like “Noise in the Park” which are just suspended cymbals set up around the hall and people are encouraged at any point to just walk up and roll on a cymbal. It’s interesting because the other thing he really specializes in is percussion music, he writes a ton of percussion music, that is part of the reason I was inclined to study with him. And so I think to me its not unrelated that he’s interested in percussion and that leads to a lot of community-based ideas. And obviously the West African music is heavily percussion based. I really like this idea of percussion being inviting in some way. I think Steve Schick talks about this, like if you leave a trumpet in the middle of the street no one’s gonna want to touch it, there’s totally like a barrier between that and a person, at least in comparison to if you put a drum somewhere. Actually I was just dropping off a tam tam for the rental company and someone asked me if they could hit it and it’s like, totally go for it.

KP: Yeah there’s also the mouthpiece situation though.

KG: That’s true [laughs] that’s a good point. So I think I haven't really dealt with that barrier on my own consciously but I really like the idea of doing something more involving of a community or with the audience as a community because that’s also how I tend to listen to music. I mean I’m totally happy to listen on my own but the activity I enjoy is playing a recording for someone and talking about it with them. And so I don't know that I have explicitly said this but with my field recording pieces a lot of the times, I mean I don't really listen to my music that much, but if I’m listening to a field recording piece I will tend to do it on lesser headphones going for a walk outside because I want to bridge that gap between what’s actually out in the field and what’s being played via the recording. And I also don’t care how people in the audience engage with the performance in nondisruptive ways. Like I super don’t care if someone is reading a book during a concert. I’ve always thought that to be totally cool and really great. And I think a large part of that is because the writing process for me a lot of times is pretty reflective of the sound that comes out and is a good way to help my mental health and, I really hesitate to use the word meditative practice because it’s not and can get a little beside the point, but this idea of having a place that I can sit and be restful in a way that feels good is ultimately what I want. So if having this music play while you’re an audience member is putting you in that place and reading a book helps with that place then great. That’s not really dealing with the barrier but there’s at least this idea of the audience as part of the performance and part of the community whether or not they’re actively engaging in a direct way with the performance or if they're kind of silently engaging with the performance in whatever way works for them.

KP: Yeah. Along the way I was reminded, I’ve heard about claire rousay, who of course started out as a straight kit player, I’ve heard of her doing shows where she’s incorporating sounds from the audience into mixes of her recordings.

KG: Yeah. I haven’t seen her shows but I’ve seen her talk about that on Twitter.

KP: Yeah, yeah. That kind of strikes me as a way where you don’t put up the performative barrier for the audience with an instrument but you can invite them to make rhythmic sounds to be incorporated into what is understood as the performance.

KG: Yeah. I also just realized another way we do this which also does incorporate some unintended sound is… well we haven’t really done a performance since covid in this kind of setting but Katie and I often for DesoDuo concerts, in part because those concerts tend to be really long, I think this started when we did Kunshu Shim’s Marimba, bow, stone, player which is like four hours, we often set a table and a hot water heater and a bunch of tea and coffee mugs. That’s partially why we made coffee mugs. So the idea is just like, I think even engaging in that way of being able to have a comforting tea or… the water heater we have is pretty loud so especially at the premier of slow, silent, singing that was a barrier that people didn’t want to cross, so I did, since Mike [Jones] was playing and I didn’t have to, I made tea. And as soon as that barrier opened, sonically speaking, more people were inclined to grab some tea and sit and engage in that way. And I think just even having something like that set up throughout the performance and allowing the audience the permission to go for it makes them active and makes it more engaging. Even though, you know, you can obviously argue that they're making tea and not paying attention to the performance. To me that doesn't matter, you're in the space and we’re all experiencing the same events. It’s just another way of actively engaging.

KP: So you finally brought up DesoDuo and I imagine DesoDuo started just because you and Katie are friends but is there a goal of the group that y’all are trying to make possible with the duo that y’all don’t necessarily pursue with your practices apart?

KG: That’s a good question…

KP: ‘Cause I feel like, you know, we just recently spent some time with Katie’s Desert Flower Diaries which have a similar aesthetic to yours in feeling very natural, simple, handmade, so it seems like y’all share a lot of aesthetics but where do y’all diverge?

KG: Yeah that’s a good question. It’s funny, you are right, we just started as friends and played some duo stuff together. The first duo we ever played together was Andrew McIntosh’s We See the Flying Bird and that was something that I think is more notated and more traditionally contemporary classical than we’ve tended to do with the duo. And that was more of us just getting together and starting to play outside of Quartet Friends, which started first. And both were basically for Katie’s recital. So I think since then it’s been both of us kind of discovering things together and showing each other things and finding ways of moving through materials that we’ve liked and have common interest in. There is not a lot of things we don't overlap in interest-wise, musically we are kind of on the same page. And so I think the big thing, as you've kind of already said, is the handmade thing. My arriving at that point we've already discussed, it just feels better to me, it’s much more natural to write things by hand, and it’s just a process that’s kind of tedious in a way I enjoy. For Katie, she has much more of a visual arts background than I do. She grew up in Tahoe and her mom is a visual artist, she’s actually the one who designed the DesoDuo mugs we have. Katie’s always grown up being a really creative person and having a lot of general, like all kinds of artistic backgrounds whereas I kind of fell into music in fourth grade because my mom asked me whether I wanted to play piano or drums and I said drums and then that’s that. As a result one of the main artistic practices that Katie has is she is much more interested in graphic scores and I think a lot of that came, particularly with Desert Flower Diaries, during the pandemic when we were both with my parents in Las Vegas. You'd have to ask her but I don't even necessarily know if the first one was created with the intention of a graphic score. It might have been. But I know for sure that it was just we were kind of isolated, we couldn't really perform and she wanted to do something creative. She has an incredible creative drive and just wants to always be making something. And so I think it started from that place and then she kind of workshopped it with me. That’s kind of a good descriptor for… I think Deso kind of lives in two places, the first is there’s just something really wonderful about playing together that we both love and it’s just kind of enjoyable to work as a duo and play with each other and enjoy each other’s company in a way… like the John Muir Trails pieces we did or Kunshu Shim’s marimba piece, things like that where it’s more of just wanting to perform. In an ideal world we perform together as a duo, so that performance base thing is really nice. And then the other side of that is both of us essentially have our own artistic practices that are super similar but will often work as like a feedback loop. A lot of the time when Katie is making these graphic scores she'll bring them to me to play, often as a solo, and that will help her inform how she wants to make the next one. In a lot of ways, I think we've talked about that together, I think we view that as a DesoDuo thing, meaning… like right now I’m doing a bunch of recordings of the desert pieces, the forest pieces, and a few other series she’s done as vibraphone pieces and we wanted to set that parameter in particular ‘cause I've done the recording for the desert pieces as percussion pieces with non-pitched things and we had talked about the idea of performing them as duos using objects that are evocative of the material, so wooden objects, things that are plant based like pod rattles, things like this, so we thought it would be interesting by having something like solo vibraphone, which other than hand-drawn lines doesn’t really reflect the flowers, at least on first impression, in a way that forces me to engage with it differently. So even though that is like Katie composer / Kevin performer, that is to us still a DesoDuo thing and will help her move forward into how she wants to develop that piece or develop the next series. Sometimes that process is just asking me what I think of it and what is interesting as a performer or as a composer and sometimes it is just, here play this what do you think. And we do the same the other way around, where I’ll show her what I’m working on notationally and she’ll play through sections of it. Or we tried recently, just for the sake of playing the trails pieces, where Katie used her chord as a harmonic grounding and then played the trails as melodies and then I improvised with some non-pitched percussion, drum set. And so part of it is just kind of coming together with new ideas and having the idea of playing together for the sake of playing. I think both of us feel like it’s really easy to get caught up in the stuff we’re doing outside of music or at least outside of performing, that it’s hard to keep up our performative practice and it’s a lot easier to just come together to do it. In some ways our goal is just to be doing that as much as possible, and in other ways we don’t have any goals intentionally. It’s more of in a similar way to writing, being a thing that makes me feel good. Playing with Katie and playing in Deso just feels good and is something we continue to do because we enjoy it so much. In terms of literal goals we have a couple recordings and people we like working with that we’re doing. I mentioned the vibraphone set of recordings we’re doing and then our friend Gillian Perry who is in Chicago now is writing a piece that I think - we’ll see what it sounds like - but it’s for two percussionists on one vibraphone so I think it might pair pretty nicely with something by Sarah like Flourish. So we’ll see but, yeah, rather than a set goal we’re more interested in doing project by project and as much as possible not setting deadlines for them so they can happen as naturally as possible. And it’s also, you know, a foolproof way of dealing with the fact that we’re pretty busy outside of it.

KP: Yeah. Well I’ve been absolutely obsessed with John Muir Trails and Songs for Two lately.

KG: Thanks.

KP: Thank you. That’s kind of all that I had lined up, did you want to go anywhere else?

KG: I think I'm good.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Jessie Cox - Enter the Impossible (2022)

Enter the Impossible premieres November 5, 2022 at the DiMenna Center in New York City, featuring Jessie Cox, Laura Cocks, Sam Yulsman, Tyler J. Borden, eddy kwon, Pauline Kim Harris, Conrad Harris, and the Sun Ra Arkestra.

Jessie Cox is a scholar, composer, drummer, and educator exploring imagined futures and new worlds. Some recurring collaborators include Ensemble Modern, String Noise, and Sam Yulsman. Some recent releases include: When You’re a Star; Alien Stories, performed by String Noise; Space Travel from Someplace Else, performed by Wavefield Ensemble; Spiritus, performed by Laura Cocks; and Nachklang, performed by Kyle Motl.

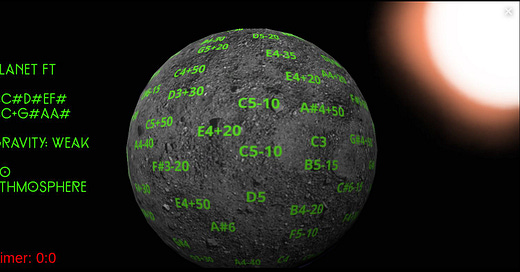

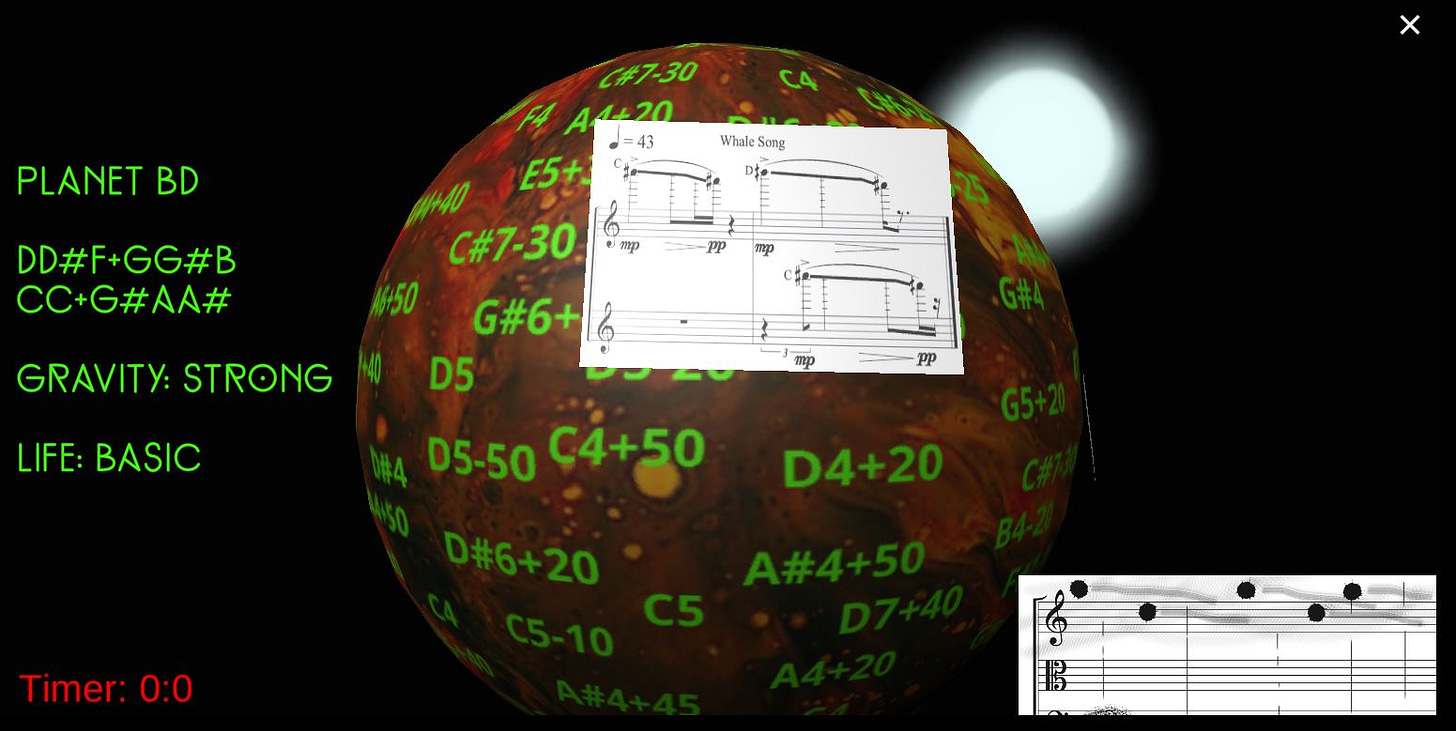

Enter the Impossible is a 2022 composition of flexible duration for drums, cymbals, and bow, contrabass flute, string quartet, and large improvising ensemble, specifically the Sun Ra Arkestra. The score includes movements in standard notation, particularly for flute and string quartet, but the bulk of the work is in three-dimensional planetary spaces navigable through a videogame. Possible focal pitches - some with cents deviation - to improvise upon pepper planetary surfaces, which a member of the Arkestra may rotate, as do occasional invitations to depart in standard notation that allow variations. Graphics upon staves in the bottom right corner of videogame pages indicate the gestural feel of a planet. Physical and biological parameters provided on the left of videogame pages influence musical parameters, such as gravity and atmosphere for speed and density, though the character of life, the influence of suns seen around the planets, and the interdependency of all these parameters are indeterminate. Each planet corresponds to a drum (LBD:large bass drum; LBD moon:snare drum; RT:rack tom; FT:floor tom; BD:bass drum), each of which are spatially distributed around the Arkestra in a way recalling a constellation or planetary system, acting as resonators activated by bowed cymbals through string like tin can telephones. Beyond planets there are special cases in this space travel, a black hole background screen indicating a string quartet movement and a planetary collision to showcase the sum and difference tones possible among large bass drum, snare drum, bass drum, and the pitch spaces related to those planets. Performances end by referencing material from “Space is the Place” and played previously from Enter the Impossible.

Navigate the videogame here.

Thematically Enter the Impossible engages with the Sun Ra Arkestra’s Afrofuturism, in which Black prosperity on the temporal horizon is realized by traveling there through space. It might also recall Anthony Braxton’s timebending worldbuilding, its videogame actualizing composed geographies, its floating notation like accelerator-class wormholes to material of another time, the spatialization of its drums perhaps similar to the Sonic Genome. And spatially-distributed drums’ acoustic ambisonics could evoke George Lewis’ multi-channel setups that are key to blurring reality and virtual reality, or realizing the imagined. In an expansive personal synthesis of these elements, Enter the Impossible locates itself as a recent point in the rich arc of Black art developed in combination with science fiction and extends it by creating a tangible pitch space as an ingenious visualization of more-dimensional microtonal music and new realization of an imagined world.

reviews

mattie barbier - threads (Sofa, 2022)

mattie barbier performs five solos for euphonium and trombone in The Tank on the 45’ threads. See the score for “untitled i” in 1/5.

The long delay of the space extends soundings and their decay sings. Brass melodies, fanfares, elegies spill from the brim and fill the room with a refracting pool of self-accompanied harmonies. The swelling domes of soundings’ tapered dynamics interact at their overlap and bounce back to accumulate and break in great waves amplifying spectral expression. The tremors and snarls of unstable techniques and fragile harmonics ripple through for gaseous forms, textures like heat distortion but from variations of pressure rather than temperature. It is as if by extending sounds horizontally they keep their scale and grow vertically as well.

- Keith Prosk

Lisa Cameron/Damon Smith/Alex Cunningham - Time Without Hours (Storm Cellar, 2022)

Lisa Cameron, Damon Smith, and Alex Cunningham freely play five tracks for percussion & feedback, contrabass, violin, and objects.

They play directly complementary and contrapuntal lines, speeds, volumes, densities. Lock into grooves of circus romp rhythms and shimmering cymbals, plucked pointillism and bowed strokes, plastic wrap melodies and more somber tunes. Bring out their toys together in preparations and objects, other objects on the drumhead, things between strings, the rake of something else along violin. And they sing together, in feedback roars, deep bass resonance, and divebombing glissandos. Apparently always attuned to the others, they convey the familiarity of continued play.

- Keith Prosk

Greg Davis - new primes (greyfade, 2022)

Greg Davis constructs six harmonic spaces in Max/MSP on the 39’ new primes.

Track titles signal the mathematicians whose prime number series inform the foundation of each rational intonation harmonic space. From the narrow latitudes of sine tones’ ascetic textures and limited movements come complex polyrhythms with orchestral range, from corporeal lows to ethereal highs, that intertongue and interact in criss cross psychoacoustics, simultaneously in stasis and spiraling. While a series of similar material, tracks might be remembered for the behaviors they engender, like the call-and-response seesaw beating of “cullen” or the sonic rivers of “sophie germain” where curves converge and bloom again into deltaic rivulets.

- Keith Prosk

Tim Feeney - Flint and Tinder (Falt, 2022)

Tim Feeney sounds two environments for percussion on the 44’ Flint and Tinder.

The notes relay some sounded objects, flowerpot shards, rusted fence, transmission tower and high-tension wires, air and ground traffic, people. The location of recording in Los Angeles county suffers drought and record high temperatures and fires raze the area. Timbral information and alternately violent and desolate density and cadence convey this apocalypse. The everpresent electric crackle of high-tension wires recalls the carbon that probably powers it. As does the ceaseless vacuum gliss of airplanes and the ominous pulse of looming helicopter purr, the latter of which is perhaps associated with fire control or rescue in this context, the former a more purposeful carbon burn and polluter of the air both occupy. The rust roughly sloughed off reminds of the essential element consumed to oxidize it. Scratched and saltated ceramic shards sound like sorting pieces of Pompeii artifacts where fire too stole the air and choked with smoke the lungs of those whose homes did not become kilns. Though likely ranch fence, a sound similar to a swivel peal against a flagpole could tie in the poor environmental leadership of nations, a sound again carried through the wind. Sounds of less resonant materials hang still in the air as if it weren’t there to carry them. Everything seems to cycle back to air and the crisis currently surrounding it. The record ends with hollow metal hit hard in funereal bell tolls that - though the object is likely ranch fence or transmission tower again - sounds like an empty water tank, another lifespring this heat takes.

- Keith Prosk

Sunik Kim - Raid on the White Tiger Regiment (Notice Recordings, 2022)

Sunik Kim arranges three scenarios - two studio, one live spliced from two performances - for Max/MSP and SuperCollider on the 53’ Raid on the White Tiger Regiment.

A rolling thunder of orchestral clusters, casino songs, circus screamers, crystalline synth squalls. Rapid speed, dense weaves, prog swings, loud sounds, petulant textures, flickering glitch gorge the ear and melt normative cognition. The music aligns with the end of time, namely decay, and that mutual deconstruction forms a crucible ooze from which new models may rise, probably political given the context of the opera with which this dialogues and shares a name.

- Keith Prosk

Hannes Lingens - Nachthund (Umlaut Records, 2022)

Hannes Lingens plays three solos for percussion on the 49’ Nachthund.

Sounds scale up from close mic’ing and high-gain recording requires night-time taping, picks up dogs in the distance and the dopey manatee moans of otherwise low-audibility harmonies, lends the inspiration to titles. “Nacht” is a multi-movement arrangement of sustained layers of fluttering, apoplectic pulses of rolls and brushes. Symphonic polyrhythms of discrete hits and resonance periodicities through skin, metal, and wood. A quiet moment with staccato wood block taps activates the whole kit in a similar, subtler way to the stippling hits surrounding it. “Hund” and “Manatee” are sister songs, for malleted and bowed cymbal. The former shimmers, sings, cultivates beatings through its shivering rhythms with the character of a club-footed growling rock riff locked in a groove. The latter is slower, quieter, lower, warmer, wobblier, darker, in multiphonic strata. The differences between the two link parameters like attack and volume to harmonic behaviors.

- Keith Prosk

Nabelóse - OMOKENTRO (bohemian drips, 2022)

Elena Kakaliagou and Ingrid Schmoliner play five songs for horn, piano, and voice on the 46’ OMOKENTRO.

The space amplifies the already rich reverberation of piano’s whole harp and the radiating glow of brass tones to further volumize each instrument’s presence for a tactile, swaddling sound. Something sounding like rain on the structure lends a warmth similar to vinyl crackle. Steel-wound strings of plucked prepared piano coo and ripple, growl in tanpura, twang like zither, and mark the time with grandfather clock chimes. Blustery breath tones, babbling sounds that carry their protolinguistic morphologies, and foghorn blows blur with voice. Like the structure they sound in rings, keyboard cross-sections, valved extensions, chest, throat, nose, resonating bodies orbiting in gravities harmonic for an interdependent system in euphonious equilibrium.

- Keith Prosk

Anastassis Philippakopoulos - piano 1 piano 2 piano 3 (Edition Wandelweiser Records, 2022)

Teodora Stepančić performs three early, multi-movement Anastassis Philippakopoulos compositions for piano on the eight-track, 69’ piano 1 piano 2 piano 3.

As the earliest available works in the composer’s catalog, I felt a comparative listen to these three pieces and more recent recordings like wind and light, piano works, and hannesson . boon . philippakopoulos might illuminate salient characteristics of these as well as the core that remains through them. In recent pieces I recall slow, soft, quiet, clean monophonic melodies whose spaciousness balances the potency of tone with the harmony of decay, the signature behaviors of which carry across performers to the extent that the pieces become more recognizable by their rest than their sounding. Pieces are short. And the next tone tends to catch the one before it just as it fades into inaudibility.

These are not those. Longer durations and multiple movements appear as multifaceted approaches to formal elements compared to the seemingly more intuitive distillation of melodies sung on long walks. Chords, sometimes their hastening accrual for harmonic excitation. Repetition, sometimes a consistent rhythmic line a bed for a melodic one, which is probably present in recent works’ melodic motifs but not reliably recognized in their speed and space. Volume, jarring dynamic spikes that excite the decay.

These elements grade in increasing delicacy through the piano pieces presented on solo pieces and songs and piano pieces, and shorter lengths and greater languor intimate an infinitesimal approach to the essence of something more of the ether than the sounds themselves. So what remains is the efficacy of decay, its signature found in “piano 3” from solo pieces and this recent realization.

- Keith Prosk

Preview piano 1 piano 2 piano 3 here.

RUBBISH MUSIC - Upcycling (Flaming Pines, 2022)

Kate Carr and Iain Chambers arrange three environments for discarded objects on the 40’ Upcycling.

Aerosol peals, splashed water, creaking cupboards, flapping paperboard. The high-floor dynamics of recycling center machinery and its concomitant metal and glass crash and shouts cut and recomposed. Anonymous friction, deformation, and turbulence, glimpses of squeaker, metal, compressed air. Sounds become increasingly acousmatic as the acoustic properties of trash transmogrify into something as synthetic as the plastics much of them might be, blending into the monkish ambience in the background, heavily delayed for cavernous auras as if the creation of a new world out of anthropogenic material manifested a new Cro-Magnon. It’s difficult to place whether sound rejoices in reuse and recycling or tolls for the mounds of material humans have buried themselves in but a darker palette suggests doom.

- Keith Prosk

Greg Stuart - subtractions (New Focus Recordings, 2022)

Greg Stuart performs two liminal compositions for solo percussion from Sarah Hennies and Michael Pisaro-Liu on the 52’ subtractions.

Sarah Hennies’ “Border Loss” is a multi-movement suite but, unlike the hard lines of something like Spectral Malsconcities or Clock Dies, diffuse transitions between movements blend them. Many-limbed nervous polyrhythms subtly shift materials and techniques by keeping some parameters the same while others change. Small dense soundings like shakers question bucketing individual sounds into larger gestures. The interdependency of limb-independent rhythms comes not just from shared time or a shared body but shared material for a feeling of sound, and the sociopolitical contexts it could signify, as spectrum.

“side by side” is a two part piece for bass drum & cymbals and vibraphone & glockenspiel. The composing and performance practice occurred side by side and the sound follows. The twinned instruments of the first part juxtapose polar play, parallel strokes and perpendicular strikes, the action curve of the former’s periodicity and the line of the latter’s and the inverse of that behavior in their dynamics, high and low registers, organic and inorganic materials, discrete hits and sustain, silence and sound, the low moan roar of skin and shrill yell of metal. Part two contrasts the first in pitched material that appears to blur the poles. A music box melody with singing decay cultivates harmony and illuminates the notion of silence as only rest and similarly the instruments’ registers, attacks, and textures often overlap so as to become closer to a shared spectrum of sound than anything discrete.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for stopping by.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.65 to $1.94 for September and $1.31 to $6.98 for October. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.