Sound American 29: The Roscoe Mitchell Issue is available for preorder, with conversations between Mitchell and David Brown & Tomeka Reid, John Corbett, Phillip Greenlief, and John McCowen and writings from Jessie Cox, James Fei, Darius Jones, Zeena Parkins, Tyshawn Sorey, Ken Vandermark, and Sam Weinberg.

The first Molten Plains Fest happens December 9 & 10, 2022 in Denton, TX for those nearby or available to travel, featuring Susan Alcorn, Ka Baird, Bitches Set Traps, Henna Chou, CNCPCN, Aaron and Stefan Gonzalez, Princess Haultaine III, Alma Laprida, Rob Mazurek, Christian Mirande, Monte Espina, Bill Nace, Warren Realrider, Kory Reeder, Luke Stewart, Marshall Trammell, Weasel Walter, and Andrew Weathers.

The Catalytic Sound Festival happens December 1-11, 2022 with streaming available for performances in Chicago, Asheville, Trondheim, Washington D.C., Hartford, New York City, and Wormer, featuring Jaap Blonk, Chris Corsano, Tashi Dorji, Ingebrigt Håker Flaten, Bonnie Jones, Lia Kohl, Brandon López, Cecilia López, Joe McPhee, Ikue Mori, Paal Nilssen-Love, Patrick Shiroishi, Luke Stewart, Ken Vandermark, Nate Wooley, Min Xiao-Fen, and many more. Streaming available for members only, with rates of $10 and $25.

harmonic series now offers paid subscriptions. Free subscribers, unsubscribed readers, and paid subscribers receive the same access; a paid subscription is just another, recurring way to regularly support the efforts around the newsletter. One-time donations donations via PayPal remain as another way. The rate will be $5 per month but this month a reduced rate of $4 per month is available for the duration of subscriptions started by December 31, 2021. A founding member subscription allows you to set the rate to anything greater than $5 per month. Please feel free to reach out at harmonicseries21@gmail.com for any questions.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $1.31 to $6.98 for October and $0.78 to $6.21 for November. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Biliana Voutchkova is an interdisciplinary artist, violinist, composer-performer, improviser and curator who uses violin, voice, and field recordings to approach new ways of expression. Over video chat we talk about intuition, sharing, personal associations, depth, and time.

Biliana is engaged with her year long project DUOS2022 and as part of it she has released a series of digital albums with Relative Pitch Records, so far including collaborators Michael Zerang, Leila Bordreuil, Susana Santos Silva, Joanna Mattrey, and Tomeka Reid.

Complementing the conversation here, Paul Acquaro, Matthew Banash, and Nick Ostrum review the iterations of the DUOS2022 series released so far over at The Free Jazz Collective.

Keith Prosk: So how’s Paris treating you?

Biliana Voutchkova: Oh, it’s good. I mean, I'm not here that long yet. I had already a few nice meetings. I met Joëlle Léandre and we’re thinking of doing something together. And then I met this other violinist, Lucia Peralta, who has a new music ensemble (Ensemble Itinéraire), so there are already possibilities for new things, it’s good.

KP: That’s perfect. Yeah I understand you have a six month city des arts residency?

BV: Yeah.

KP: Nice. Is there kind of like a deliverable at the end of that or is it just "hey come in and enrich our city with your music"?

BV: Well, I think they’re more interested in providing space for you to just work peacefully. It's a Berlin-related residency, the flat and the stipend, everything is from Berlin. So I just can do what I want. I mean I’m doing the duo project here now, meeting a lot of people and just doing one-on-one work. So we’ll see. But also open to things I can not yet know. I have already one concert scheduled on Nov. 13th with cellist Séverine Ballon, so it will be… we will see how it goes. It’s very nice to be here because France is one of these countries where I almost never come, very rarely. And also a lot of musicians that work here, they don’t travel as much. So you actually end up meeting many people you wouldn't know about unless you come.

KP: Nice. Well, I've got a little map going from some of your solo stuff and working up to the duos, but at any time if you want to take it in another direction I'm glad to go there. Is there anything that you want to start off with?

BV: I think let’s just do what you want to do, and then I think at the end if there is anything I really want to say that we haven’t said. It's good like that.

KP: Yeah. So let’s start with your voice. When I think of strings and voice, some of the other players that might come to mind are like gabby fluke-mogul and Charlotte Hug and a lot of times their voice can appear almost as an extension of the strings. I liken it to a karate chop, where the vocal energy is almost aligned with what is perceived as the energy of the music. But with your voice I feel that you’re using it in a bit of a different way, almost contrapuntally in line and texture. So one of the sounds that I think about a lot from you is that groaning gnawing sound, which is quite a bit different than the shriller sustain that might characterize a bit of your violin sounds. But of course I think you think of your violin and voice as one so, I guess… in what ways do you approach incorporating voice into your string practice, or how do those two talk to each other?

BV: It’s interesting actually that you say that, because a lot of people tell me my voice feels like an extension of my violin. Like many, many people. And they usually address it as it is just an enriching color palette of my violin colors. But I can tell you how I see it. First of all, it started appearing very organically without necessarily a conscious decision to start using the voice. So it did come out as an extension, searching for new sounds, which of course is an ongoing practice (to search for new sounds). And I remember that it was quite intuitive. This was when I recorded my first solo, Modus of Raw. I was at a residency in Switzerland in the Alps, in a little town called Poschiavo, where I had three weeks. I remember what happened is that I was already using the voice a little bit, but not much, it came organically here and there in my performances. In Poschiavo I had a kind of a small studio set up and I went hiking in the mountains a lot, like almost everyday, maybe six to eight hours, with a few free days in between. So I did these really big nature hikes and then I came back to my place and I recorded in the studio pretty much every night after that. There was a kind of connection to nature and physical activity, and just intuition. And often at night I was quite exhausted, but that even put me in a better state to play because I just didn’t think, I just played whatever. And that was the time when the voice came a lot, more and more and more. And I just noticed it. Usually that’s how things work. I notice I'm doing something, I give it more attention, and then I let it happen more and more. It’s also sometimes with certain techniques or whatever, they appear a little bit and then I just shift my focus that way. That happened with the voice. So I started consciously using it and saying "OK, that’s coming, let’s see what happens… " So that was the three weeks intense period of using it more and more, and since then I've been using it pretty much always when I improvise. It’s part of my vocabulary now.

KP: Yeah. And so you mentioned Modus of Raw and that’s kind of what introduced the world to your voice and violin together and then the next solo, Seeds of Songs, added field recordings on top of that. And with Seeds of Songs it kind of seems like they’re there because those sounds had become such a central part of your experience while you were locked down during Covid. But then they pop up more. They pop up recently in the duo with Joanna Mattrey and there they seem to have a little more utility, where they provide a more constant contrast to the more spontaneous string playing. So how has incorporating field recordings been developing, or are there some goals in mind with incorporating field recordings?

BV: Yeah. Actually I don’t know if it's goals, but it's definitely kind of the next thing that’s appearing more and more organically in my work. I just mentioned how the voice came, and in a similar manner, I started using field recordings for the first time a couple of years ago. And again, the first kind of milestone and public presentation of that is this Seeds of Songs solo album. For me these two solo albums are landmarks: the first one, Modus of Raw, is where I first officially introduced the voice. And then the Seeds of Songs, a landmark of a completely different process, using field recordings and unrelated material as a starting point, rather than organically seeking, playing and just putting it out as it is, which is the case with Modus of Raw. Seeds of Songs is pretty much a composed piece, where I have taken material from various locations or moments, and that happened throughout these Corona times obviously, and I edited the material in a totally artificial manner in a way. But for me it's really… I find complete logic, everything belongs together for me. So it is still an organic process. From the point of view of someone outside it may not be, because these things are coming from random times and random places. So the Seeds of Songs is somehow the landmark and the first official milestone of my work with field recordings. Which, again, is more and more coming into my practice. I have been recording a lot, but I have not used any of the material until that point. So I started using it and finding ways to work with it a few months before Seeds of Songs came up, and continuing until now actually. Joanna’s recording is a good example of that. I also had an exhibition last year where I used the field recordings for some of the installations. And I also have another new solo project where I use a mini-speaker installation. I have ten very small speakers, I use between five and ten of them. Usually I prepare a soundtrack with a combination of field recordings, sometimes violin and voice, any of these, and I play with it. So it's a very spatial solo because the speakers are completely autonomous and I can put them anywhere in the space. In the case of the gallery where I had the exhibition last year, they were used for one of my installations and I played with them. That is how it started. This is the way that I'm more and more incorporating the field recordings in my solo performances now.

KP: Nice. You mentioned a logic that is there for you, but might not necessarily be there for outsiders. Say, for instance, the sounds in Seeds of Songs. Are those connected sonically to you or is it more of a spatial or experiential connection or a mix of those and other things?

BV: It varies, really. Some of them are associated with a person or a place. Which is completely personal and of course nobody can know that. And it's not relevant for people, but for me they connect to a certain experience or certain state of mind that I'm in, and I feel like "oh now I'm gonna record that". And also it’s not really again a conscious… I'm interested in the subconscious, the kind of dreamlands and otherworldly levels of expression which can come to the surface. I noticed that certain times what I do with the voice resembles a song. And that again has not been much the case before, because I use the voice a lot in terms of just sonic expression, it’s not really songlike, very often it's really sound work. For Seeds of Songs, it's really singing in a way. It’s not really developed songs, but that’s why I called it Seeds of Songs, it's really like little motifs of something that is songlike. And that’s how I connected the various recordings for that particular release, because they have these kind of songlike qualities for me. That was my logic behind it. For the one for Joanna, again it's a field recording from a particular place where I was with a particular person for a longer amount of time. There was a garden there where I spent quite a lot of time, so I started noticing certain details and they all connected for me. Then there is one recording on that album which is not from the garden, but it's from the moment that I left. And I started listening to these birds just before I took my flight, and it was just somehow like, wow these birds are kind of like saying goodbye or something. I don’t know, again it was very personal, but I notice those things and they connect for me, so that's why I put them together. So yeah. And I called it Like thoughts coming because certain thoughts were related to these recordings and they were also related to the way that we played with Joanna. Again, something that I connect for me and it makes complete sense, but maybe not for anybody else. For Joanna M., thank god! it did, because of course we work together. She loved it! And there’s also a little moment where there is a cat coming. You hear this little cat moment and Joanna adores cats, we were even thinking of putting a cat on the cover. So there are all these things which completely connect and make sense, and that’s how I present them to the world.

KP: Perfect. So you do also have Amati Lenta which… I understand you previously did some work with Olivia Block and there’s a future series on the horizon around that kind of work. And that’s when you’re in duo with a field recordist. So do you find that you feel a difference between working with your own field recordings and working with someone else’s field recordings, when that connection might not necessarily be there?

BV: Yeah, yeah of course it's different and that's why I do it. Because I like difference. So the way that this particular piece works is that I actually work with mini tape recorders. I have five dictaphones and there are particular modules that I recorded on all of them, where I play certain material. It is a kind of a piece that has a couple of modules which can come at any time in any way, but they are recorded on all of the five dictaphones and because of the essence of these little dictaphones they sound completely different [laughs]. Sometimes the same material is unrecognisable as such, but I recorded it on all of them simultaneously and they just sound like nothing else. So this first performance of Amati Lenta was with Olivia Block. When I do a collaboration we always do it in a way that the person I work with makes their own decision how and what to use, they add their own material too. So there is like a little melody that is always the same, there are certain sections that have harmonics, one that is more percussive and then at the end there is a section with a waterphone. So all of these components are always present in each variation. For example with Olivia, she wanted me to actually record a digital version of what I had done with the mini tape recorders. We recorded it and then she used also that to process for her own sounds. There is also a solo version of this piece, but I have to admit I really quite like to collaborate with others for it, because the piece becomes something very different and at the same time the essence of it, the core is the same. You hear it and you just get to hear these little glimpses of the modules, but everything else is completely different. Maybe I should mention the collaborators that I have for next year when we will releases a tape series of Amati Lenta. I already did the first recording, it’s with Svetlana Maraš, I don’t know if you're familiar with her work. She’s Serbian, but she is now the head of the electronic studio in Basel, Hochschule für Musik. She’s moved to Basel I think a year ago and we did a recording at the studio there. The way that she chose to work is to use the big magnetic tape machines and rerecorded material from the dictaphones on those big tapes, and then she only used these sounds to play with. She worked with changes of speed and eq’ing, no processing, and she did not use any other sounds that she normally uses. So that was her take on the piece, to actually use the… lenta in Bulgarian means tape, so she only used the actual tape and she only used physical tape which she cut and did loops and all kinds of things. It was really a very different working process, very physical and tactile somehow. And then I am planning to… so there are going to be three collaborations, one was with Svetlana, one will be with Marta Zapparoli from Berlin, she works with tapes a lot, of course. We are in touch and planning that next year. And the last one will be with Angélica Castelló from Vienna who of course also uses recordings and tapes in her work, we will be meeting and recording in December. She will be my guest for the last DUOS2022 concert in Berlin. And so we will also use the time to work on Amati Lenta. Then the plan is to release these albums on cassettes and digital, in collaboration with Shameless records, an Austrian record label run by a colleague of mine, Boris Hauf, who lives in Berlin. And he invited me… he really wanted to do it with Olivia, to do the original work, but she is in Chicago and we’re not able to schedule this right now. I suggested the multi releases, I'm really looking into possibilities of ongoing projects which develop over time. So that’s why I suggested three colleagues for now, and it could be that it becomes four or five, it depends on what possibilities we have. But for now with these three we will definitely do it. It’s kind of a DUOS2022 extension really, but it's for me very different because it's an actual piece and there’s an actual core material for it, so it's not completely improvised and so, yeah, that’s for next year.

KP: Yeah it sounds like you sit with things or ideas for quite awhile right because we were talking about the progression from Modus of Raw to Seeds of Songs, there’s this iterative process of duos, and now this tape project as well. So Boris reached out to you initially?

BV: Boris reached out to me when he found out that I worked with Olivia Block because he really loves Olivia’s work. I was in Chicago, and Chicago is also a very special place for him, his wife worked there and they have a very special connection to the city, so he really wanted to do something. It’s still possible, it could be that we end up recording with Olivia at some point, but somehow not now and yeah, he really was excited about it. And then when we talked about other people he was just like "ah you know what, let’s just do it like that."

KP: Nice. So we’ve talked a bit about voice and field recordings, but people probably consider you more of a violin player. You’ve got at any one time a lot of different kinds of projects going on, anything from the more traditional sounding notated stuff with Ernstalbrecht Stiebler to a lot of the more textural free play that's going on with the DUOS series or even Jane In Ether, but do you see a throughline with your violin work, or are there some ideas or actions that you find yourself returning to all the time?

BV: Yeah. So I’ll separate a little bit the question. The first thing that people do associate me with is the violin of course, mostly because that’s my main instrument. That’s a thread since I was four years old, no wonder that's how people think of me. I do want to shift this perception though because, especially around the last ten years, I have done so much more than just playing the violin. I've done a lot with the voice. And I've done a lot of performative work, also with dance, I had a dance and music group for ten years called Grapeshade. So many, many different things. And I do like to be treated as an overall artist, musician, because my work is going through waves of interests and the violin is always present, but I am not only a violinist. As I said, my work goes through waves of interest and at the moment I am very much inspired by the connection between people, people and places, places and places, and as a result the working with field recordings appeared. And also I'm very much interested in other visual work and in general visual inputs. I like to work with visual art, with video or with images as an input, maybe even graphic scores, taking the visual in a broad sense... again, it's not something that has to be visible for others, but for me it's the next wave somehow. It’s working with installations, making my own installations, having this first exhibition performance last year where I use the installations as part of the overall composition, where I play with them, this is kind of the next chapter that is interesting for me. And this connection between places and people that I mentioned is also very much connected to the duo project because the people I connect with, they come from various places and they somehow infect the way that I create, make me do things differently, because I am a very responsive player. I am usually responding to something when I improvise. So this is to say that I don’t necessarily want to be connected to the violin only, but it still is a very main part of all my work, it's one part of everything that I do regardless of the shifts that the work takes. And then you said, is there something that I return to. I mean, I have created a certain language that I use and I think I kind of make an analogue, well, to language in general. We have a language and we use the same language and the same words, but we say different things. And it's a similar situation with the way that I play. I have created a certain language and I use it to say different things. Obviously, consciously and subconsciously, I do return to things, but at the same time I am trying to find ways that provoke me to do different things and also to surprise myself. That is why the whole duo project came, the whole interest in visual input is also very present right now, the field recordings, all these things are coming because I long for finding ways to make me respond differently and eventually find something new. So far it has been efficient, I believe it will continue being efficient for the future [laughs] And the other thing I want to say, because I also play written music, it's a similar wish. I like to work with composers. I'm more and more interested in dropping out of already-written pieces and creating pieces with composers that are written for/with me. Like the collaboration with Ernstalbrecht Stiebler that you mentioned, we have known each other for over thirteen years, ever since I moved to Berlin, and there has been a lot of exchange. We also improvise together sometimes, and so the pieces that he writes are really written for me after knowing me. This is a different way of playing written music as it would be a piece that I just get the score for. Recently I also commissioned a piece by Anna Korsun which is for violin and voice, and I love it because she uses the voice in a way that I can totally relate to. Another recent piece by Peter Ablinger, which is also a release called An den Mond - same thing. We had two weeks time together to create something. And so this is definitely different because this is composed music by someone else, but it is at the same time a shared collaborative process, what he calls “al-fresco composition”, and it makes me do things that I could not think of by myself, they come from outside. This I really like. Everything that I do with the improvised or composed music is definitely beneficial to the other. It’s always enriching.

KP: Yeah there’s always that nice feedback where not only do, say, different kinds of making music feedback to each other, but interacting with different mediums of art or forms of art or even sciences or different activities, kinetic activities you said were feeding back into how you make your music with the Swiss hikes…

BV: Yes, completely, I am a nature lover, so I am in nature a lot. I think I even want to be more in nature and almost never in cities any more, but we’ll see about that [laughs] My work is related to cities and to these very vibrant artistic scenes that you find in cities and big metropoles like Berlin. I mean, that’s the reason I'm in Berlin. I cannot be the person and artist I am if I am all the time living in the mountains by myself. It’s also about sharing. A big part of the work is really about sharing and if I don’t have that I don't think I can create. Sharing is important.

KP: Yeah you mentioned that these duos are infecting your play. You also mentioned you kind of like to work in series because it's tracking changes, pushing you to different things. So with the DUOS2022 series, one of the things that I picked up on is that I very much hear the characteristic of both players, and I also hear how they’re kind of blending or meshing as well. So sometimes this happens very texturally, like your breathier bridge bowing works perfectly with Leila’s subway rail squealing strings or Joanna’s really rough sawing, but also of course listening to each other through dynamics and densities and stuff like that. So that exchange feels like a core part of why DUOS is happening. But are there some other goals going on with the project?

BV: Yeah. Well, as I said, the project came first as a wish for very direct communication in a creative sharing world. I find it very special to share with one person, so that was the first idea, I wanted to do that for a long time with different people. The goal is to bring out the different qualities of the way that I create in response, in relation to my partner. And I think this is becoming evident by listening to all the records, because you see how all these differences are coming out and they’re definitely related to the personality of the person I am playing with. I mean, I am the same player and again, I probably use a language that is similar, but in context and in relationship to the different partners that I invited, it’s just a completely different sound world, and I love that. I love to see how this transition is happening and how much individuality and personality matters in the way that we play and in the way that we create when improvising. For me it's fascinating, it's magic, you know. It's the same instrument, but with different people completely different music comes out of it. Some tracks are thirty minutes long, some tracks are snippets from couple minutes from here, couple minutes from there, with connecting to field recordings and things like that. For me it's fascinating, I love it because, again, I have this project for a long time and I can get into the details of the differences, follow them and create that way. And you know, I have worked like crazy for many, many years and the kind of way that I worked was that I jumped from project to project a lot. And that’s related to lifestyle. I'm a single mother of two children, I'm a freelancer, and I had to do that. So there has been a lot of projects in my life where I jumped from playing contemporary music theatre to improvising the next day and the next day I play with my new music group a hardcore Pierre Boulez piece and then I don’t know what, and this has been happening for twenty five years, and I have enough of it. I want to have longer times to focus on one thing. This longing for dedicating time to one project and going much more into detail and depth with that project ended up with the DUOS2022 project for this whole year, with the wish to have residencies as I have the residency in Paris now for six months, where I can really take the time to focus on less things and on my own work. So that's how it came.

KP: Yeah. So somewhat similarly, a duo that you've had for a very long time is Michael Thieke. But how might that kind of long, developed relationship compare to these duos, which sometimes are first meetings?

BV: No, right, it's a very different process because we have grown together and played together so many times that we know each other’s language. There are not so many surprises in terms of like… I mean, of course things are always different and surprising in some way, but I know his vocabulary. The reason that the interest in this long-going one-on-one work with one person is also there because we can go into depth in a different way. For example, we start working with collaborations of all kinds, like we did a project for our tenth anniversary called it Materiality & Sound, where we worked with a furniture designer Rainer Spehl in his atelier. We recorded the sounds from his machines in his working space and connected to the materiality because he works a lot with wood, and our instruments are both wooden. And so there was this connection between the way that wood transforms, then we took the sounds and used them with our Blurred Music concept, so we created again a long durational piece. It was a five hour long piece and we played it two days in a row. So we played for ten hours for our tenth anniversary. We add an element of surprise by thinking of ways to complement our playing and to shift the focus to the details, to add something external, something that we have not done yet. It’s fascinating because the reaction and the sensitivity is so deep by now that we can grow on top of that with adding additional elements.

KP: So you've kind of implied that with the sharing there might be a certain kind of intimacy when it's just between two people. But is there something that the duo format kind of makes possible that a trio or even larger, like your stuff with Splitter [Orchester], it's just not there?

BV: Yeah well it's of course very, very different, especially with a large groups like the Splitter. Splitter is all surprises, always, even though we know each other super well. And also I have to say I think in duos you can understand the other very exactly. For example, let me see how I can explain that... it’s a very fast process, so it doesn't go through thinking and saying, “oh I know what she’s going to do” or “I know where we are going". The brain cannot follow that fast, it's very intuitive. But we know or at least I think we know the other person’s intentions and wishes and decision making instantly. So if I play with one person, I would know that now is the end of the piece in an instant, maybe even before it comes, but I'm like, “OK we are at the end in one second”, and it comes in one second. The decisions are made simultaneously by both with no room for misunderstanding. With a group that is bigger you may think you know, but you don't know, you have no capacity to follow everyone, because then there will be one person that decides, “yeah, well I don't want it to be the end”, and then it's not. When it's a duo I think you are more going into depth by risking more and trusting more. And in bigger groups, first of all you take yourself away much more often. There are a lot of other people in Splitter and you often don't need to contribute in any way, so it's better to give space. It’s more that you are locating how the whole strange apparatus and soundscape functions and then you only initiate when you need to and you are most of the time just sensing. And I think in duos, you read it so fast that you can take shifts like this [snaps] and you know the other person will follow. I don’t know, it's just a different process. I'm in general a person that likes the small, I like the minutiae of life. I like this word. Two people is enough, small place is enough, playing for one person, great. Small spaces, I don’t necessarily love to play in a hall of three thousand people. I like it in some ways sometimes but, you know, I like the small. So it's natural I'm drawn to a duo or trio because these are the smallest ensembles possible.

KP: Nice. So now you've had quite some time that you have been sharing with all these different duos, since DUOS2022 has been going on, how have you found that’s impacted your approaches when you go back home, away from the duo?

BV: Yeah. Well I think it's curious to follow how each one is shaping because they’re all very different. For example, the one that I think I’ll release as last is a collaboration with Charmaine Lee from New York. And with her we will not meet and we will not record together. I gave her some images to look at and respond to them soundwise, and she sent me some recordings, so it's more like exchanging and creating a piece out of this. It has not happened that way with the other albums. Somehow I thought it will be more often that I work this way, with sharing files long distance, but actually I ended up meeting and playing with all the other people. And again, I like these little switches, little differences. The way we recorded with Joanna, we recorded shorter tracks and they really were like some thought is coming and then we follow like little birds, and we did that. With Leila, it's completely the opposite, it's long graduating transformation of material that kind of shifts, but it's kind of progressive and slowly developing. And so I come home and I listen to the material and the interesting work for me is to edit it. To see what is it that's different from the other and do I keep the original, or do I hear things differently. Sometimes I edit things completely and compose with a whole other palette of material, like the record with Joanna with the filed recordings. And sometimes I let it stay just as it is, like the one with Susana Santos [Silva]. There’s nothing touched there except the few reverb parts. But again, we recorded in a way that there were so many close-up mics and you hear the sounds really like it's in your head, and I thought it would be nice to have sections where suddenly it's like you go out. Every one of them gives a hint of what could happen and then I catch this hint and I go that way. They definitely give me an input, the music itself, the personality of my colleagues and the way that we play together gives me an input of what will come out as a result with the album.

KP: So you mentioned with the Amati Lenta series that Boris contacted you but how did you connect with Kevin [Reilly] at Relative Pitch [Records] for the DUOS series, publishing that, if you're willing to share?

BV: Yeah. Kevin is someone that supports the whole improvised scene worldwide as much as he can. I have to tell you, we are all so grateful to have a Kevin and to have this label. He is so incredibly supportive. And so he knew my work, he actually helped me to connect to Leila at first. We played a concert in New York a few years ago and it was because he connected us. He was interested in putting out a record that is not digital, an actual CD release, but I am a little bit starting to doubt how much of CD's I want to put out in the world. I do like physical objects, but I think this format is somehow questionable. Also I had the idea of doing this DUOS2022 project with the live concerts and then also having multiple albums released and I just asked him, you know, instead of releasing CD's can we do a series of digital albums. He normally doesn’t do that. And so this was actually a suggestion, an idea that I had, and he embraced it, he said, sure if that's what you want to do let’s do it. As I said, he’s just supportive to each individual and to the way that we want to work and be creative. So he embraced the idea and he said, let’s do it, and he’s putting it all out and he’s an amazing and wonderful collaborator.

KP: Has there been any kind of method to how you're selecting people to play and release duos with or has it just been people you've enjoyed playing with over the past year or so?

BV: It's more like people that I would have liked to play with, but I haven't. Or sometimes, like in the case with Michael Zerang or Susana Santos, we played in bigger groups and we had other things happening, but just to play duo with them. And some of them, like Joanna or Charmaine, that was a first time meeting. So it's always different. The selection is simply based on the wish to play with musicians who I admire.

KP: Yeah, and did Leila and Tomeka’s happen during DARA [String Festival]?

BV: Yeah this was also a kind of coincidence. The next release is with Tomeka actually. I didn't plan it that way, but I was invited by the Goethe-Institut in Chicago to do a collaboration with Tomeka online during Corona. There was a series called Bricolage, curated by Magda Mayas and Dave Rempis, and they each invited an artist from their respective city and decided how to match them. So they invited Tomeka and me for a match to do an online project basically. And then the whole thing became very interesting because that same year Tomeka invited me to participate at her string festival, the [Chicago Jazz] String Summit, which was an online edition of the festival. And then I invited her to my festival (DARA String Festival) and we didn't know if my festival would be online or if it would be live because it was a Corona year. It ended up that actually for the summer months in Berlin the concerts were happening and so I had the festival live and then she actually came to Berlin. So we were together and we thought, well c'mon, we are together now, we are not gonna do an online presentation when we are in the same room, we can just play together. And so we recorded together, then she left and then the online presentation which was the format for Bricolage was actually a film that I created. It was my first self-edited film, so this will come out together with the release. The image material was when we actually did the long distance exchange. And at the same time it happened that Leila was already going to be a part of my festival, so I just thought, OK then I have two cellists and it's fine, and then I recorded with both of them.

KP: Yeah are there some goals of the festival beyond presenting string music, like if you're focused on premieres or first meetings or advocacy?

BV: I'm focused on all of that [laughs] The main focus is to mix the people from the different scenes. Obviously the festival theme is string instruments, but also the main reason to do it is to mix musicians from different backgrounds. Some people come from self-taught background with self-made instruments, some people come from heavily classically-trained background and their most adventurous playing is contemporary music, that is kind of not even nowadays contemporary music, others come from complete experimental noise background etc. My wish is first of all to create a possibility to exchange between us. It's not only about presenting to an audience, but it's also about us meeting. And that's why for me it's important that everybody is together and plays on both days of the festival, and everybody presents their solo so all of us can hear each other. And then play in different groups. I curate it in way that people which come from different backgrounds can actually meet and play a piece together in some way. Like in the case with Susan Alcorn and Mari Sawada who would normally not have a meeting point to play together. It was a commissioned piece by Clara de Asís for two violins and a pedal steel guitar written for three of us. I am focused on all of that, creating new pieces, new relationships, new groups, giving a chance to people to play a solo for each other so the other musicians which don’t know much about certain kind of music get to hear it in it's best :) I'm very happy to say that the feedback I have gotten from all the participants is amazing. They write me such incredible letters, I tell you, it's so touching! All of them have been extremely happy, nobody ever complains and everybody encourages me to go on. And this is for me the reason to keep doing it. I started with the idea of doing it one time, I wasn’t necessarily thinking to go on. If there is a goal for the festival it is to do guest editions in different cities & countries. We did first time guest edition in Köln and in Wuppertal last year and it was beautiful. So there are thoughts about doing a guest edition in New York, co-curated with Leila. We actually had this idea two years ago, but then it was Corona and everything fell apart…

KP: Nice. So you've mentioned a lot of exchange and the love for strings in your life is obvious and I imagine that exchange maybe can happen… a little more transposes across strings, but is there another reason it's very specifically a string festival?

BV: Again, I just want to focus on details and go into depth in general with my work. I like string instruments, I am a string player, I'm curious what kind of possibilities there are when consistently engaged with the topic. I discover things myself. So this is just going into depth with what is possible, what kind of string instrument music can be there and who are the people creating this music, which may not be the first ones that come to your mind. Like Annette Krebs whom I invited, she made a self-made instrument called Konstruktion#4 and there is a certain part of it that has strings. You wouldn't necessarily think of it as a string instrument, but I see it that way.

KP: Perfect. That’s all I had mapped out, but did you want to go anywhere else?

BV: I think that’s it. As a final, I'd like to underline again that I have worked so much jumping from project to project and it's really exciting to have consistency in some of my work now. I really love it. I think I almost want to drop out of occasional playings except, you know, I will not completely, of course. I'll keep on some of it because it's also exciting to do a great project that is unexpected and it's happening one time only. But not all the time, definitely not. I would like to focus more on ongoing projects. My ideas and my wishes are very ripe now, I know what I want to do, and it's the time to dedicate myself to that. I go for it and I find a way. Berlin is very good place, very supportive for the work of individuals and the freelance scene. And also I would like my work to be more visible at least in the European scene. Because of my life circumstances I wasn’t able to travel as much in the past. It’s possible to do it now and that's why I would like to be more mobile and to share my work more widely.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

Davíð Brynjar Franzson - violin fragments (2019)

Davíð Brynjar Franzson is a composer. Some collaborations include The Negotiation of Context with Yarn/Wire, On Repetition And Reappearances with Mivos Quartet, The Cartography of Time with Vicky Chow, Mariel Roberts, and others, an Urban Archive as an English Garden with mattie barbier, Russell Greenberg, Ryan Muncy, Halla Steinunn Stefánsdóttir, and others, voice fragments with Stephanie Aston, and strengur with Stefánsdóttir, in which a realization of violin fragments appears. Davíð is part of the Icelandic composers collective S.L.Á.T.U.R. and co-runs Carrier Records with Sam Pluta and Jeff Snyder.

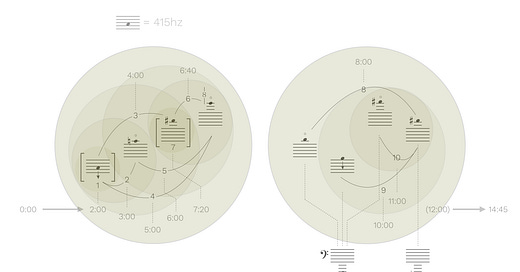

violin fragments is a 2019 composition for solo violin, twenty artificial intelligence voices, and live electronics with a duration of fifteen minutes. Performance direction is communicated verbally. Floating pitch material appears to be arranged on the page so that height correlates with relative pitch. Numbers arranged left to right and their corresponding timings indicate sequence and their associated arcs umbrella possible pitch material, e.g. the ninth element can include the three rightmost pitches under its arc. Shaded circles also indicate the groupings of possible pitch material in each element. Standard brackets invite repetition for some pitches. And while the electronic environment reacts to all sounding, the two pitches floating below the cloud of the eighth element indicate pitches of the electronic environment that activate upon registering the corresponding pitches played by the violin as designated by the dotted lines.

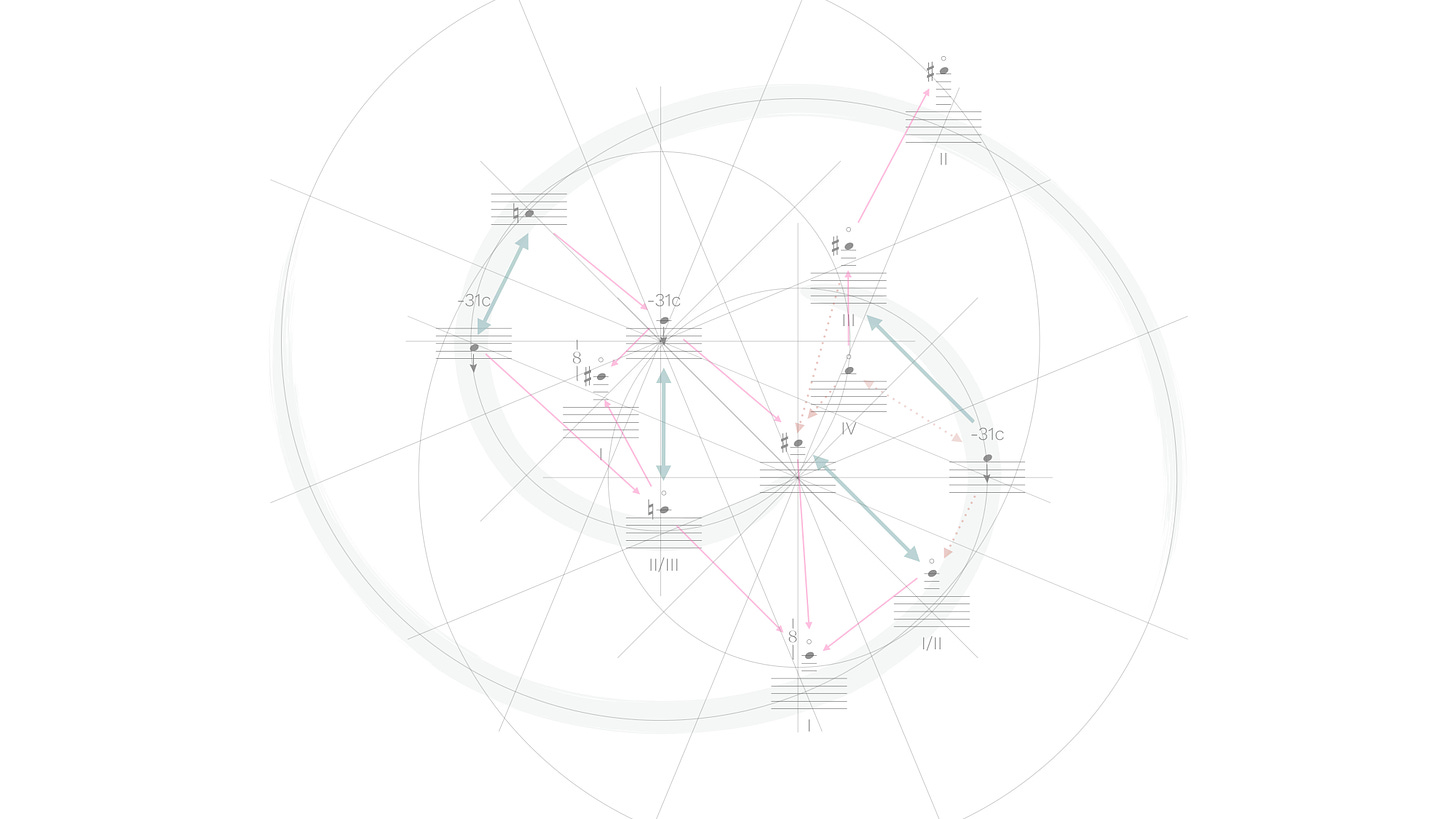

The clock time, numbered sequencing, height signaling relative pitch, and shaded circles seem like logical signposts for the performer. The latter illuminates the structure and provides a visual reference for the expansion and contraction of material in the first set and contraction in the second. Breaking the staff, retiring tempo, and respatializing pitch into clouds drives home the choice of shape, or how a performer might arrange the available material in the time block allotted. And the aforementioned clarity of presentation allows the performer to focus on this task of shape. Sound material exists in the blank space but it is not for the performer and could be considered rest. While two sets of overlapping clouds might suggest a separation and rest, I imagine the electronic environment can be excited in ways that bridges the two sets if silence is not settled upon. The final minutes too, though that would seem to unbalance an otherwise very symmetrical structure when no play in the first minutes means no sound, unless it’s decided upon that the contraction of material can be associated with decay.

It is an uncommon treat to present sketches on the path to a current version of a composition. The relationships are more mysterious but it feels like a more personal notation towards figuring out desired groupings via circles and lines and sequences via arrows. Circles in particular appear to assume new meaning as seemingly connected pitches don’t fall within overlapping circles or, in the case of the sketch above, all pitches are contained within each of the larger circles, which suggests location within circles contains meaning. While circles within the current version have more clearly defined functions, maybe something gleaned from the sketches in relation to the number of circles a pitch falls in or their proximity to an edge or center can be reconciled between the two to color an interpretation.

reviews

Léo Dupleix - Préludes non mesurés (albertineeditions/nunc., 2022)

Clara de Asís, Richard Comte, Lauri Hyvärinen, Fredrik Rasten, and Denis Sorokin perform selections from fourteen Léo Dupleix compositions for solo guitar on the nineteen-track, 54’ Préludes non mesurés.

Melodies of deliberately paced and deliberately placed tones and chords of tones occasionally combine at the overlay of their attack and decay for singing harmonies. Of the fourteen pieces the performers realize seven, only one of which would not allow comparison across performers and only one of each acoustic and electric that would not allow comparison across kinds of guitars. Mélange sequencing makes disorienting straight-through listens possible alongside those by piece and by performer. More than the melodies hear performer personalities and signatures in articulation, speed, spacing, and instrumentation. Fredrik’s breath and deep-chested guitar resonance. Denis’ muddy, bluesy sound. Lauri’s arachnid dissonance. Richard’s clarity. And Clara’s bold attack, string buzz, contingent sounds, and extended durations. Making time malleable makes the performers audible.

- Keith Prosk

Eventless Plot - Memory Loss (Moving Furniture Records, 2022)

Chris Cundy, Aris Giatas, Vasilis Liolios, and Yiannis Tsirikoglou realize two reflective forms for bass clarinet, piano, psaltery, tapes, synthesizers, and programming on the 32’ Memory Loss.

Warms swells in overlapping relationships of labyrinthine sequencing in permutating repetitions of slow celerity disorient the listening memory to whether a moment is past or present. Layered like leaves sounds choke silence like the mind manifests curvilinear surfaces for memory from its fragments. The two structures feel similar enough to wonder whether they’re transposed across textures as confused contexts, iron lung rhythms and biomorphic clarinet forms for organ throbs and water whose character is more soothing sound machine than field recording and melancholy piano melodies. Both lend a sense of swaddling nostalgia equal parts nursery and hospital recalling that those who live long enough would have a memory as much as the day they were born, and these pieces’ ends are not so different than their beginning.

- Keith Prosk

Jason Kahn - Soundings (Editions, 2022)

Jason Kahn reflects through text on seventy-seven minute snippets of urban field recordings on Soundings.

An impression of plain language in terse and earnest diarism makes it difficult to tell whether words’ consonance is accidental or intentional and relatedly the columned layout might manually redistribute the weight of words’ cadence to mimic the broken percussion of natural sound or emphasize words and clusters of words if not simply an automatic product of the format just as the framing of the recordings - titles, durations, presentation - accidentally or not coaxes the ear to see meaning in otherwise unedited urban noisescapes. The semi-poetic text doesn’t illuminate the specific context of sounds so much as the complex web of associations of location the author recognizes. The recordings are dense and muddy and ordinary. Recurring events like church bells, trams and trains, and salsas, magnetisms toward the om drone of refrigerator hum, industrial facilities’ churn, and hvac units’ thrum might manifest a sense of place in another listener. When the author says something like they can tell the age of the trains by the creak in their bones I think I can too. There is an empathy for timbral information and maybe a transference of their personal associations. The author mentions a memorial resonance and while this surficially refers to a personal experiential sustain it could also mean across minds in the shared memory of a globalized people with an urban condition.

- Keith Prosk

Henrik Munkeby Nørstebø - DYSTOPIAN DANCING (MADE NOW MUSIC, 2022)

Henrik Nørstebø plays a sidelong track for trombone, amplification, mutes, and plastic reed and arranges its remix with additional accompaniments on the 39’ DYSTOPIAN DANCING.

High gain close up microphone placement desublimates the ghost in the air for dark, cold atmospheres that complement a multi-movement menagerie of visceral, hostile sounds, piercing stridulations, low growls, racked gasps, baleful purrs. But the dominant movement is a rhythmic sputtering in envelopes of action at the lips, through the breath, and in the structure the texture of which shifts among effervescent, metronomic, organic, machinic. A heightened consciousness around a kind of beat based on variations in mouth morphology, pressure, and capacity ties time to the body, ups the stakes, and feedbacks into its violent undertones. A wide rhythmic palette provides much material for its reworking, which adds eerie noir and air raid sirens, glassy sines, and the ubiquitous clicking of an object orchestra, and the rhythmic raspberries blend with bumps that could come from programming as much as the mouth for a kind of breath-based dub techno.

- Keith Prosk

Guilherme Rodrigues - Acoustic Reverb (Creative Sources, 2022)

Guilherme Rodrigues sounds the spaces of eleven churches across fifty-eight vignettes in nearly as many minutes on Acoustic Reverb.

Herringbone bowings and dulcet pizzicato surround silences spacious enough to hear sounds’ delay, decay, and interplay within and with the architecture. A keen ear could parse damping, room size, and other parameters but even generally the characters of each space convey themselves in the differences felt in their reverberations. The space seems to color the cardinal sounding though, even with a wheelhouse of technique, unsystematic sounding makes it hard to examine particulars of the space and location within the space. Regardless, the rich reverb of every room ripples to realize the fluid that fills its container and what is a cup but for its contents.

- Keith Prosk

Masahide Tokunaga - Leverages 杠杆 (Zoomin’ Night, 2022)

Masahide Tokunaga breaths to life two 25’ realizations of a composition for alto saxophone on Leverages 杠杆.

Long soundings as long as deep breathing swell in organic intervals. Breathy subtones stir beatings of variable properties. More than saxophone it sounds like feedback, smooth and squealing. Parabolic arcs alternate with linear curves that in turn furcate into resonating harmonics to lend a sense the sound zooms in and out of different scales. The smooth pleura of the lungs and the rough edge of alveoli. Inhalation and exhalation and the ordinary irregularity of them. Open and at attention. One bustles with water, anonymous movement, and knocks and beatings and one with the quiet night and multiphonic furcations, the breath and the body seemingly mirroring the activity of the day.

- Keith Prosk

Biliana Voutchkova, Tomeka Reid - Bricolage III (Relative Pitch Records, 2022)

Tomeka Reid and Biliana Voutchkova play three communications for cello, violin, and voice on the 28’ Bricolage III.

A distanced pandemic commission of the eponymous series, the music contains tethers to a visual component as part of its presentation. A desaturated film reduces scope from clouded sky to forest canopy to molting tree and pans across the detritus of the forest floor towards the performers’ fists tight as acorns opening across and alongside each other in a gesture of exchange and growth. And then the vibrancy of foliage resounds in clusters of red, yellow, green, magenta flowers so intense their colors could be treated and then their overlapping hands open to bloom alongside the sound. The sound reflects this kind of cross-pollination in a dynamic equilibrium of the two through texture, speed, density, and dynamics in which each keeps their individual characters and also converge for profound moments, like the gaseous overture unveiling ghostly voices, a swarming hive of gliss, and train horn cello echoing fiddled harmonica.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for sharing time with harmonic series.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). For the nitty gritty of this system, please read the editorial here. harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $1.31 to $6.98 for October and $0.78 to $6.21 for November. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.