Kyle Motl recently published Bells Plucked From Air: a guide to (mostly) pizzicato harmonic techniques for the double bass to words of praise and anticipation from Mark Dresser, Olie Brice, and Louis-michel Marion among many others.

Issue 81 of Point of Departure is available, featuring Bill Shoemaker on George Lewis’ “New Music Decolonization in Eight Difficult Steps,” Troy Collins in conversation with Thumbscrew, Stuart Broomer on Mosaic’s Classic Black & White Jazz Sessions, Evan Parker in appreciation of Gerd Dudek, Kevin Whitehead on Mal Waldron, Ed Hazell on baritone saxophone repertoire, Greg Buium on Paul Bley, excerpts of books Improvising the Score and Sound Experiments, and reviews of The African OmniDevelopment Space Complex and The Cricket: Black Music in Evolution 1968-69.

Daniel Barbiero recently published “Earle Brown: The Poltergeist in the Machine” over at Perfect Sound Forever, on open scores, chance, and failure.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.78 to $6.21 for November and $0.85 to $4.52 for December. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

award

harmonic series offers a share of all donations received to the musicians and related folk that make each issue possible through their communication, editing, and generosity. But there is always a choice to not receive it. These funds accrued in a pot to be awarded with inspiration from Pauline Oliveros, who in the preface to Deep Listening reflected, “Validation by peers and critics and the small cash prize from Pacifica Foundation were encouraging and appreciated by me. I was no longer alone with my passion to compose, and I continued.” If we could only hope to provide such support to such a one. So we try.

Beyond the small cash prize, which this time was a bit less than $200, the award in this particular instance is also an attempt at wider advocacy and recognition of appreciation from a broader audience. The regular contributors to harmonic series composed a short list upon which just shy of fifty musicians that gave to the pot were invited to vote. We are thrilled to announce the first recipient of the harmonic series award is

Natalia Pérez Turner

Natalia Pérez Turner is a cellist, interpreter, and improviser based in Mexico City. A regular member of the ensemble Liminar, some recurring collaborators include ensemble colleagues Omar López and Wilfrido Terrazas. Few recordings are widely available and activity is largely localized but what is available is profound. Through an email Q&A we talk about challenges, different ways of thinking, intuition, and dogs and cats.

Keith Prosk: Are there some recurring qualities that draw you towards pieces to perform, like something in the imagined sound, a certain field of interpretive tensions, or something else?

Natalia Pérez Turner: I think it is something that has been changing with time… Firstly, I don't choose to play music that I'm not really interested in playing, either because I've listened to it or because, for one thing or another, there's something in it that really draws my attention to it (it's usually very instinctive, I think it's the first time I'm actually looking for a reason to choose to play a certain piece of music) or because I'm interested in a composer, on trying to learn about his/her music and creative procedures. For example, there was a moment I was really interested in learning as much as possible on extended techniques so working on Xenakis' Nomos Alpha some time ago, which is a piece I've always loved, helped me develop certain techniques, extended my knowledge of the instrument and helped me to learn about Xenakis' thought and creative processes. I have friends who say they don't want to work on written music, or in music by anyone else, but their own. I can't remember who it was, but I remember reading about a writer who said he had started to write because he didn't find anything he wanted to read anymore. I'm not there yet. I feel that, as in good improvisation, playing a piece by someone else can be like a rich conversation with the music, with the composer, with my instrument, and also with the place I'm performing and the way sounds carry in there. I still like to do both, improvise, do my own stuff and play other people's music. And I like to be challenged, to be taken to places where I might feel uncomfortable, and although that can happen in an improvisational situation, I feel it happens a lot more when playing written music. Obviously there's lots of challenging music that I'm not interested in playing. I've worked Julián Carrillo's sonatas because I'm interested in microtonality and wanted to work his approach to it, but I'm not very keen on his musical ideas, and in the way he structures his pieces, so I work on them for myself and if one day I find something in them that makes the music exciting enough to perform any of them, besides the fact there's only one recording of the full set, the music is hard to get and they're very rarely performed, something exciting for me in the music itself, I will… I suppose, in the end, what draws me towards certain music is its sound and musical ideas. The composer's creative process and the creative possibilities as a performer are very important, but if the sounding result of a piece doesn't resonate with my interests I'd find it very hard to choose to perform it.

KP: I've read that at least Marcela Rodriguez developed a piece for you and that there are pieces you've developed collaboratively with composers. When a composer creates or co-creates a piece for you, what are some qualities they've tried to express in your approach to sound and/or your cello?

NPT: I think it's mostly a matter of flexibility, I'm not a virtuoso player, but I'm willing to try stuff and suggest sounds, techniques or musical ideas once I understand what the composer is looking for. Some people have said that they like my sound or my approach to music.

KP: I'm sure there's a bit in both, but how does your performance practice complement your play (stuff that leans more improvised) and vice versa?

NPT: There's a continuous feedback between my improvised music practice and everything else. If I'm writing music for a film, once I've seen it, and seen a particular sequence several times imagining sound or music, I sit and improvise with that. There's a dance piece, the music started as an improvisation and then certain ideas got grounded and I worked on from there. I think improvising has helped me develop musical intuition, a musical and technical freedom that I was a bit afraid of when I first started to play solo. At the same time, playing written music gives me not only the enjoyment of discovering different musical universes, different ways of thinking about music, but also broadens and enriches my approach to the instrument and sound itself. Sometimes by chance, I've found ideas I'd like to follow, for example, one day, in a recording gig, while the people in the studio were talking about what to record first or something like that, I started to explore tiny gestures, which would be almost soundless if there wasn't a microphone there and that opened two paths, one, without the microphone almost completely soundless, and the other one, amplifying these almost soundless gestures.

KP: Are there throughlines or motifs you find yourself returning to in sound, whether that's textures, tones, feelings, techniques, ideas, so on?

NPT: Of course. I think everyone has a certain language, sounds, ideas, etc. that make a sort of a "musical self.” Sometimes I try to forbid myself to use certain sound material, or ideas, in order to explore my instrument further, sometimes I discover things I want to explore further, and become part of my language. As a listener I love to listen to how people develop ideas and sounds through time, how they construct a language, how it becomes more and more unique and, at the same time, it can be surprising, fresh and moving.

Listen to “Duo 1” from Christopher A. Williams & Liminar’s On Perpetual (Musical) Peace?

KP: I feel like there are few recordings of amazing CDMX players, yourself included, and when I might stumble across a release title it's often difficult to locate the audio. Whether that's due to limited access to recording and distribution, cultural leanings towards accentuating the ephemerality of sound, inattention from the rest of the west, or something else, what do you feel contributes towards this?

NPT: I suppose it's a bit of everything, there are recordings that are no longer available, that were made in a small batch of CDs, for example, the master got lost and because of one reason or another it hasn't gone on to streaming platforms. When a recording is released on CD, cassette or even vinyl, they are usually sold in concerts or in small independent venues (concert venues, book shops, etc.), some also go on to bandcamp or other digital platforms, for example, but not all. I do see lots more recordings coming out both in streaming or physical formats from musicians elsewhere. I suppose there's something cultural there, although I'm not quite sure of what it is. Maybe it would be easier to understand it by taking some distance.

Although it is easier to produce recordings now than 10-20 years ago, and there's people playing every week, it's easier to find things in video format of their work. Is it to do with ephemerality? I don't think so, maybe in some cases, but if that was the reason you wouldn't be able to find anything at all. This is just a theory, but maybe the fact that we don't travel as easily outside the borders with personal projects (for economic reasons or visa related reasons) makes the world smaller in a way. People are playing for more or less the same audiences all the time, it can be lots of fun and there can be great music coming out of there but it might not be very attractive to make a recording of that because it can also get a bit repetitive. So maybe making a recording is a way of going out of this circle, for me, that's a reason to start a recording project, but… we shall see. So far, my personal experience is a mix of recordings of concerts or recording sessions that got lost, or that never got anywhere because time goes by and the excitement for the project might not be there anymore, or after listening to it again, it's not as good as we first thought, either because the music is not as good or because the recording itself is not very good.

KP: I understand you're a dog lover, contribute towards humane efforts for dogs, and care for a few of your own. What do you think your dogs think of your playing? Do they ever comment or play along?

NPT: I love dogs, but I haven't had one for quite a while, even though I'd love one. When my last dog died, I was so heart broken that I decided to take a break. Now I live with cats, stray ones that decided they wanted to live here, and I've adopted. One of them is very old and not very friendly, timid and nervous, she doesn't like the other cats, so, maybe when she's gone, I can start to think again about bringing a dog into the mix. I don't know if they like my playing, I think the youngest one doesn't like high pitched sounds very much, but both like to sleep near when I'm practising, even a stray cat that comes for food or to sleep in a sunny spot doesn't leave when I practice or play near him. Same thing happened with the dogs I've had. There was one that really hated recorded saxophones. He'd start howling and I never thought of it as singing, it sounded more distress, so I never rehearsed with sax, flute or clarinet players at home when he was alive.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

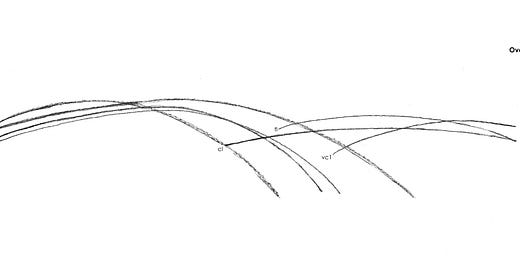

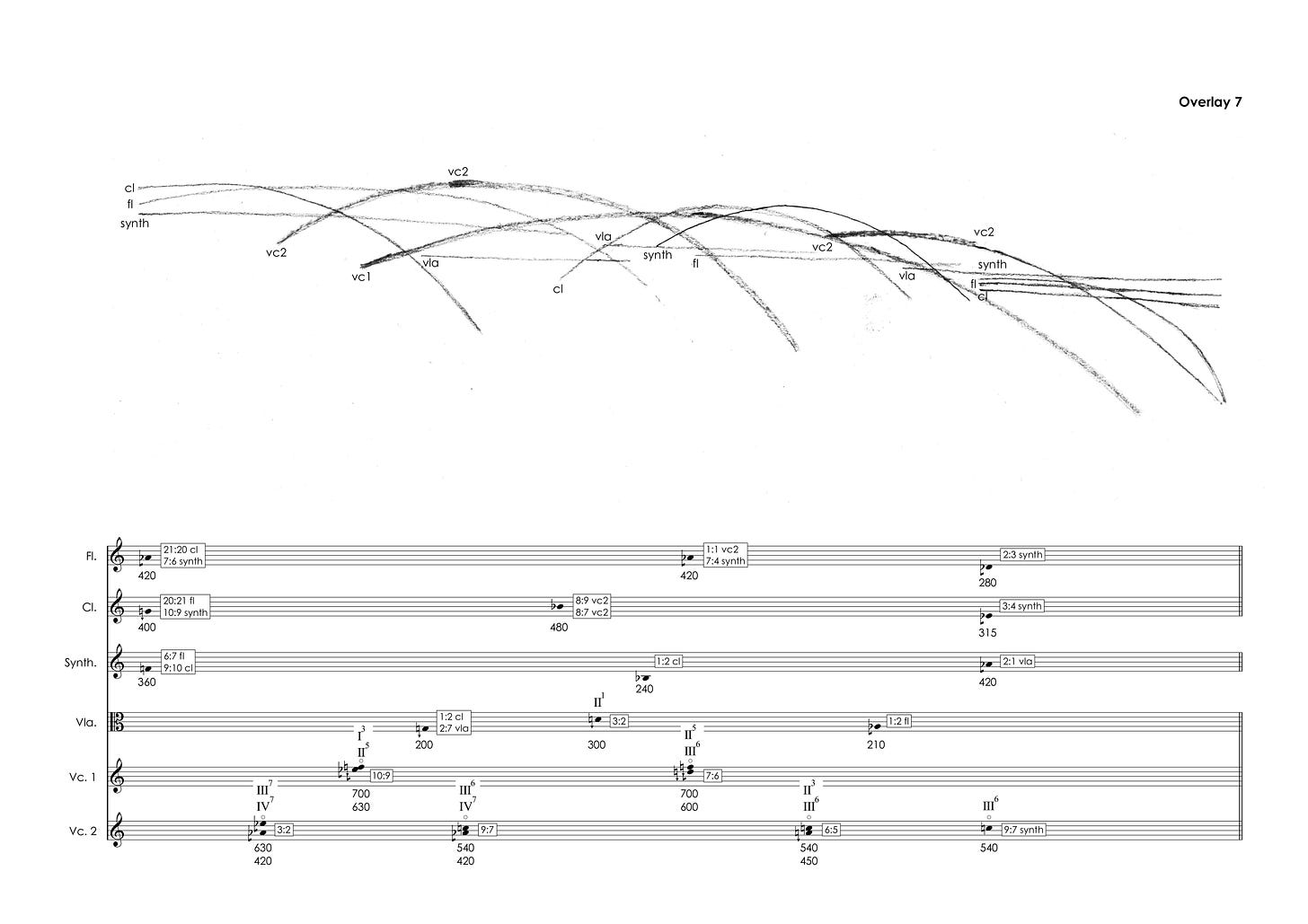

Catherine Lamb - overlays transparent/opaque (2013/2022)

Catherine Lamb is a composer and interpreter concerned with the color, shape, and perception of sound and plays viola and synthesizer. Some recurring collaborators include: fellow Sacred Realism artists Bryan Eubanks, Andrew Lafkas, Rebecca Lane, and Xavier Lopez; fellow Harmonic Space Orchestra artists M.O. Abbott, Sam Dunscombe, Judith Hamann, Jonathan Heilbron, Lane, Thomas Nicholson, Michiko Ogawa, Lucy Railton, Fredrik Rasten, Marc Sabat, Sarah Saviet, and Chiyoko Szlavnics; and Johnny Chang as Viola Torros. Recent releases include: Muto Infinitas, performed by Heilbron and Lane; Aggregate Forms, performed by JACK Quartet; the secondary rainbow synthesizer solo Inter-sum; Prisma Interius IV, performed alongside Eubanks and Lane; Yannick Guédon’s a s p e _, performed alongside Guédon and Lane; and (in) tone, performed by String Noise.

overlays transparent/opaque is a series of seven arrangements for six musicians with instruments of subtle contrast. The 2022 revision for Ensemble Mosaik allows for moderately more malleable durations which, besides different instruments, might be the most noticeable change in instructions from the 2-3’ suggestion of the 2013 and 2018 versions for Ensemble Dedalus, who perform the sample realizations. The score contains scordatura for applicable instruments and a key to its Extended Helmholtz-Ellis JI Pitch Notation and other tuning information on the page. Beyond the structural choices around selecting, ordering, and separating arrangements, instructions indicate relative height means timbral presence and an example realization of an arc suggests techniques and textures for the roots and apex. Arcs are of different thicknesses, intensities, and radii relative to other arcs and some parameters might change within an arc. Sometimes arcs of the same instrument overlap. Each arc is one tone. There is an explicit goal to explore relationships between individual and collective tones. Like the color paper exercises of Josef Albers’ Interaction of Color, each arrangement explores the interaction of tone, their illusions and listener perceptions.

And like Albers’ exercises, practice doesn’t often manifest expectations, so these are certainly better listened to or better yet performed than imagined. In the pedagogical spirit of that inspiration, an order of arrangements might begin with those containing distinct arcs or clusters of arcs before moving towards arrangements with even more complex overlapping relationships. Perhaps more than a relatively static image, the time-flexible medium of sound and the phasing relationships of arcs closely approximate Albers’ moveable color paper exercises to explore the shades created between two colors in different placings and spacings. The slightly shortened or extended durations the 2022 revision allows might influence perceptual effects in nuanced ways, perhaps similar to how canvasses of different sizes featuring similar material would.

reviews

Jessica Ackerley - Wave: Volume I (self-released, 2022)

Jessica Ackerley realizes aspects of the ocean in a four-track suite for solo electric guitar on the half-hour Wave: Volume I.

Electric waves in so many ways convey the flux of the ocean surface. Voluminous swells, arced slides, trance pulses, and the long sustain of undulating decay in overlapping relationships phase and synthesize. Effervescent arpeggiations, glistening melodies, and the tempestuous turbulence of a stuttering distorted chord baffled and broken by the bars stir the calm of the long tones like the land, stars, and air work the water. It effects a comfort similar to soothing sound machines in the mimicked movement of the subject even with waves’ strata of noise depicted in thinner lines.

- Keith Prosk

Marja Ahti & Judith Hamann - A coincidence is perfect, intimate attunement (Second Editions, 2022)

Marja Ahti and Judith Hamann arrange two sidelong sound plays for recordings, synthesizer, organ, piano, and cello on the 34’ A coincidence is perfect, intimate attunement.

More than a tower of babbling superpositions sounds arrange in series of lateral facies changes inviting the ear to hear resonances across environments in literal and literary senses. The reverberations of spaces are felt, in churches and hallways, maybe the hard walls of truck bays. Timbres blur together, snoring or string or old wood housing, and even composers’ contributions could not be discerned but for piano and cello. The beat of electric current and the period of sine waves are not so different. Things vibrating and shaking. In harmony from afar just for the contingency of sharing time.

- Keith Prosk

Nick Ashwood - Transparent Forms (caterpillar, 2022)

Laura Altman, Nick Ashwood, and Jim Denley perform an Ashwood composition with clarinet, acoustic guitar, and flute on the 29’ Transparent Forms.

Guitar’s slow bowed tones’ tanpura blends with winds’ long tones long enough to fetch waves spilling beatings between the three. The rolling curves of the frictional bounce of string and fragile shake of breath intertwine too. There’s a sensation that rather than emerging from the drone the winds subside into it to become one. But their shifting overlays are not so much a convergence as the neighboring components of the same light split into timbres that color the perception of each other and blend in their shared spectrum. Six or seven segments signaled by significant silences seem to sound the rainbow, each of them as subtly distinct and distinctly dimensional yet fading into one another just as the violet that needs the red on the other end of its flat representation.

- Keith Prosk

Bryn Harrison - A Coiled Form (Another Timbre, 2022)

Sarah Saviet performs a Bryn Harrison composition for solo violin on the 56’ A Coiled Form.

A barrelled and variably pitched springing spiral curve of a knotty step function melody the fast flowing surface of which glints fragmented with details of its larger structure in nauseous repetition and suspension sounding the double helix dynamism of kinetic and potential energies along an elastic and extended duration. The same things that no doubt make it manually fatiguing make it aurally fatiguing, speed, density, repetition, duration, so while glimpses of recurring events or those similar enough to trick memory and their expansions manifest the essence of the structure it is difficult to track its actual shape with the ear and so appears an ouroboros run through the hands searching for an end only to look and see it tangled again.

- Keith Prosk

Clara Levy - 13 Visions (Discreet Editions, 2022)

Clara Levy performs Pauline Oliveros’ Thirteen Changes for solo violin with possible harmonizations for selected Hildegard von Bingen chants on the 80’ 13 Visions.

As harmonic substrates for Bingen’s relative pitch melodies there’s a sense of stillness but in seemingly assuming chants’ unmetered time there’s also a sense of movement. Oliveros’ text reflects this dialectic too. The ebb and flow of the moonlight tide of the baptism of the music is a constant of change. Atomic solar systems’ electron clouds corral what is there that could be anywhere and is not there. The repetition of a comet’s orbit shifting in each iteration from the gradual loss of material and tacitly its relation to the other celestial bodies that must also shift between visits. Scale is inversely related to perspective and a reduction in the former yields an expansion of the latter. With her the impossible is as easy as play. And the range where audibility fades to feeling is met with a complement to unheard melodies. Rich multiphonic harmonies whose singings are as florid as the winds’ turbulent eddies. An intuitively happy pairing thanks to the performer’s vision.

- Keith Prosk

Misaki Motofuji - Yagateyamu (Hitorri, 2022)

Misaki Motofuji plays a multi-movement solo set for baritone saxophone, clarinet, electronics, recordings, and whistle on the 45’ Yageteyamu.

The fricative hiss of only breath through the bore sounds like a storm just outside yet distant from which breach overtones which branch into more with more forceful breath. Saturn missile whistles overlay to the point their density blends with long tones that beat and stridulate. Breaking waves of breath and key clicks like drip drops locate themselves alongside recordings of water. Bellicose baritone train horn bellows, textures shifting towards bass drum rounded on the skin around its rim or visceral contrabass arco. Ending with water and breath again. A mercurial music, in its incorporation and mimickry of air and water, flowing transitions across the spectrum of its cadre of instrumentation and smoothed movement from discrete tones to long ones to the swift beats of overtones, the interchangeable timbral identities of water and much of its instrumentation. Like water or air it does not stop moving but only cycles again.

- Keith Prosk

Eli Wallace - pieces & interludes (Infrequent Seams, 2022)

Eli Wallace creates four pieces with three interludes across two sidelong tracks for solo prepared piano on the 47’ pieces & interludes.

A menagerie of textures without borders. Though time marks interludes of piano as tuned percussion the boundaries are as fuzzy and incidental as those in the dialectic of composition and improvisation. Roulette pills. Celestial wobbles. Fluted strings’ exotic birdsongs. Sorting lentils. Funhouse hyperpiano. Floor drum churn. The characteristic key tones of piano are unrecognizable and only the rich reverberation of its so many neighboring strings alludes to it. Thunderous harmonies come from rhythms determined by the decay and character of clusters of textures in turn determined by the material components of the piano. A small revelation that material as foundation for music is as intuitive as material as the foundation of sound to write a love letter embracing of the whole instrument.

- Keith Prosk

Sam Weinberg - An Afternoon Solo, 2022 (self-released, 2022)

Sam Weinberg plays six saxophone solos on the 26’ An Afternoon Solo, 2022.

Two standards, 40 I, from the time when Braxton’s compositions were rendered in alphanumeric strings and geometric schematics, and Keith Jarrett’s Mandala, whose sound celebrates the complex repeating forms of its title’s subject, clue to the thrust of the rest. Sets of discrete tones permutate across cells in similar cadences to create a sense of shifting repetition. Like irregular tesselations. The infinitely branching tree of life from a few nucleobases. The kaleidoscope of a Rubik’s cube’s rotating constellation of colors whose changing combinations necessarily affect the perception of their neighbors while the whole could be said to remain as much the same. And while staccato soundings make for a distinctly structural feel the juxtaposition of different colors and shapes of pitch sequences conveys vibrant if tacit textures. The momentum of the tension between change and same is also carried by a sense of firm precision from a kind of mathematical intention abutting against the contingencies of dogs barking, beer cans cracking, and motorcycles passing as well as the rougher edges of play, the spherical cow and the physical real.

- Keith Prosk

Yan Jun - 51’28” (Firework Edition, 2022)

51'28" follows up Yan Jun’s previous untitled album for Firework Edition which, as far as I can tell, was a 53-minute recording of the artist taking a nap. It’s possible that he wasn’t asleep at all and was actually in complete control of his breath, it’s hard to tell. 51’28” follows the extreme minimalism and singularity of that album, but does away with the ambiguity – he even states exactly what is happening on this album in the description: leg-shaking, recorded during one day in Finland. It’s obvious when you listen too – this album really is 51 minutes and 28 seconds of leg-shaking.

However, as Yan points, out, “leg shaking is not an easy action”. It requires patience, concentration and stamina – both from the performer and the listener. As Yan focuses on his shaking legs and the sounds they make, he invites us to join him. It feels very intimate for this reason, listening feels like sharing a body with the performer – I can even feel my own leg shaking to the rhythm.

It’s such a natural performance – controlled by the body’s own rhythm, the power and position of one’s joints and muscles. This plays a big role in that intimacy. It’s a completely organic musical language, fully honest and transparent, yet it expresses nothing at all – or rather, nothing more than “I’m here, I’m alive, and my legs are shaking.” So rather than just sharing musical ideas, this release shares specific attributes of the body – insignificant non-actions that typically go undiscussed, and are usually only observed at length by loved ones or close friends.

There is also a more literal natural element here in the sounds of birds and wind that generously make up the background of recording. It’s soft and comfortable, like sitting outside on a park bench, or maybe on a porch with a cup of tea. But again it adds to the intimacy of the recording, because the longer this soft background drags on, the more convincing it becomes as part of my own. So it’s not just an invitation to share a body, but one to share a space as well.

This album probably comes the closest to the quote Yan Jun’s been using for a long time, “I wish I was a piece of field recording.” If he didn’t openly state what was happening here, I’d probably assume this whole thing was a field recording, and that the leg shaking was something natural to that environment – but who’s to say it isn’t, or that the leg shaking sounds can’t become part of their environment? If bird chirps and buzzing bugs can be considered natural to that environment, then why can’t a human shaking their legs? Why can’t Yan Jun’s human presence in that space be a piece of field recording?

Despite all the concepts, 51’28” is a surprisingly easy listen, like the previous untitled album was. It doesn’t demand much or carry any surprises, it doesn’t provoke feelings or anxieties. It just, for the duration listed in the title, exists. And when it ends it feels as if a certain tension has been lifted – it’s not just that the leg-shaking affliction has dissipated, but the entire environment has. It makes me want to immediately put it back on again, to bring the whole thing back to life.

- Connor Kurtz

Yan Jun - hongkong (No Rent, 2022)

hongkong is the finale to a trilogy of releases (also including europe and Lanzhou) made by Yan Jun for No Rent Records over a five year period. The music is primarily performed with feedback, and achieves a remarkable aesthetic that falls somewhere between contemporary EAI minimalism and classic, cathartic, screeching noise – a style that very much feels Yan’s own.

Through these three releases, the progress of Yan Jun’s style can be clearly felt. Where europe was uncomfortable, surreal and harsh, and Lanzhou found and honed into a meditative calm within the bleeding feedback, hongkong manages to combined both worlds and present something both aggressive and peaceful, evocative and stoic. It feels more refined than ever too, with rigidly structured songs and consistently excellent sound design.

The feedback performances are consistently on the edge of technical mastery and sonic unpredictability. There’s a clear attention to detail and frequent attempts to make specific sounds, to express specific ideas, to generate patterns, but the feedback system always, at least somewhat, speaks for itself. And while Yan tries to control and guide it, there’s also an essential acceptance of this, even a glamorization of it in sustained sections of uncontrolled feedback tones or eruptive clipping.

Because of this unpredictable nature of the instrument, the performer is always both on the inside and the outside of these sounds, playing both the designer and the observer. It turns the performances into something simultaneously explorative and expressive, where sonic introspection is met with somewhat failed results. There’s a constant tension because of this, as Yan Jun perpetually attempts to shape the sound into an ineffable goal – as the perfect sound is polluted by an electric squelch or clicking, and that new sound is honed into instead, making for another perfect sound.

On top of this sonic tension, there’s some emotional or political tension here too. It’s hard to explain exactly why or how or what is being expressed, but these decadent walls of self-destructive feedback give me images of urban decay and cultural collapse, with speakers and mixing boards stacked in a trash heap, and these modern technologies only being salvaged to be presented as archaic and impractical sound devices. I can imagine it as the sounds still present in the now-useless technology left behind after human apocalypse, or the amplified electric sounds of a contemporary tech-infested apartment, suggesting that the era of technological abundance, electric cacophony and industrial waste is both a futuristic concern and already here.

Beneath and within the pure feedback stoicism is a cautious, worried personality. I’m sure the emotional takeaways of a work like this are largely in the ears of the listener, but I feel a massive anxious tension here. It’s in the performance, there’s both joy and anxiety in the erratic instrument – indulgent excitement and nervous restraint in each gesture, creating an air of caution that surrounds the performative curiosity. This feels perfectly reflective of the potential political and cultural anxieties that can come from observing industrial decay, of worrying for the future or even the present, or of witnessing culture mutate and sound on its own, possibly under the guiding pressure of invisible hands.

This is an album for people who lean in to listen to clicking computer hard drives or buzzing outlets, who enjoy the imagery of urban decay and industrial nonsense as nature, or who gain a perverse excitement from when their audio equipment malfunctions. It’s extreme in a unique way – it’s piercing and uncomfortable, patient and claustrophobic, cryptic and raw, harsh in sensibilities but restrained in approach. Maybe what’s most exciting and extreme is the purity of it – that Yan Jun was able to find such a single, powerful, potentially off-putting aesthetic, that he’s been able to refine it to such a degree without losing its edge, and that he was able to fully excavate it into such a cohesive and subtly varied album.

- Connor Kurtz

Zhu Wenbo - Four Lines and Improvisation (Aloe Records, 2022)

Zhu Wenbo performs a solo composition and a solo improvisation for sine tones, voice, microphones, clarinet, and snare drum on the 33’ Four Lines and Improvisation.

Sustained slow vocal hums that could at times be confused for electronic modulations move alongside sine tones that beat as both approach unison, the perception of space reflected through the hiss of recorded silence changing with changes in each from which the crunch and crackle of sensitive microphones also emerge. Long shrill clarinet tones gradually appear closer to the dulled roar of feedback distorted through snare drum whose modulations fishtail towards new equilibria. The two seem hues of the other despite differences of instrumentation and composition. And within them there’s also a sense that the sound sources blend and converge and collapse into each other. The reduction of things doesn’t isolate them but illuminates the relationships of its many and disparate components.

- Keith Prosk

lists

Celebrating 2022 recordings.

Connor Kurtz

Mark Vernon – Time Deferred (Gagarin Records). I fell in love with this the first time I heard it. Mark had sent me an early copy after I reviewed two of his recent albums (In the Throat of the Machine & Magneto Mori: Vienna) in 2021, but I had a hard time finding a way to review it. The previous albums were both easy for me because they relied on specific concepts and clear ideas, but Time Deferred contained neither – instead, this album is held together by a vague feeling.

It’s a cryptic sense of dread, something personal but twisted into a fragmented, Picasso-esque face. It’s a series of audio-dreams and nightmares that are built from dissected memories and subconscious emotions. Each track is rich with something ineffable – be it an ethereal nostalgia, an anxious terror, an unrequited longing, a temporal confusion, or a bitter regret.

In Time Deferred, the concept of ‘time’ contorts into itself – memories and recordings get laid out on a flat plain together like they do in the resting subconscious. Tapes being sped or slowed reflect a mind obsessing on ideas or feelings, while their processed and twisted nature reflects the mutated, stylized way an uneasy mind remembers and feels.

It’s a powerful, cohesive and intricate album that could probably mean something different to anyone who hears it, as they attempt to understand its emotions and experiences with their own. If there is one album I’d like to recommend from this year, it’s this.

death’s dynamic shroud – Darklife (100% ELECTRONICA). A joyfully bastardized chimera of a pop album, degenerated, degenred and degendered as if rendered by imperfect AI. There’s moments of human emotion played against moments of superficial ecstasy or dysfunctioning surrealism and the production is a disjointed but engaging mesh of aesthetics, both exaggerated and nuanced. It’s catchy, complex, so creative – a really fun listen.

Bruno Duplant – Le jour d’après (Sublime Retreat). There’s a specific sound on this album that really appealed to me, it’s a soft high-end scratching – it could be a tape-head failing to read dirty media, or a repetitive scratch, or a glitching effect left behind by the temporal rift that was opened to make this album. Le jour d’après is a single half-hour ambient piece built from dusty tapes, discarded memories and forgotten musics – it’s nostalgic, bittersweet, and gorgeous.

Jürg Frey / Reinier van Houdt – lieues d’ombres (elsewhere). Jürg Frey’s compositions are patient, imaginative and beautiful, and Reinier van Houdt plays with the perfect restrained sentimentality for the part. There’s a musicality in these pieces that makes it stand out from other Wandelweiser music – the sparse, soft melodies, the momentary lushness, the comforting repetitions, the beauty – but it has thorns too, as introduced by its opening dissonant chords. For fans of Wandelweiser music or contemporary piano music, this is probably essential.

Reinier van Houdt – drift nowhere past / the adventure of sleep (elsewhere). Two excellent albums – one comprising Reinier’s 6 monthly tracks made for the online AMPLIFY 2020 festival, one all new. Reinier’s compositions are so cool – there’s clear inspirations from the various artists he’s collaborated with or interpreted, but the results as a whole sound nothing like them, it’s very much in a hard-to-define style of Reinier’s own. The songs are linear collages, typically with a dreamy narrative flow. It’s evocative, mysterious, thoughtful and very creative.

Annette Krebs – Six sonic movements through amplified metal pieces, paper noises, strings, sine waves, plastic animals, objects, voice, a quietly beeping heating system and street noises (Graphit). For an album with such a long and specific title, it’s surprising just how surreal and unpredictable this is. It’s an elaborate mess of pops and pangs and clunks and clangs that hints at a reason to its madness which it never gives away. It has a strong aesthetic that’s consistent throughout, but there’s constant variation and nuance enough to keep it exciting and unknown.

Francisco López / Reinier van Houdt – Untitled #400 (i dischi di angelica). The first track is a composition for stringless piano – I had to read that a couple of times before realizing how strange it was. It’s all expertly recorded wooden, percussive thuds soaked in the vague notion of tone. The sonic options are limited, so it feels like they thoroughly exploit the instrument for all its worth on this track. The second track remixes the first one, mutating the piano thuds and tremors into fully unrecognizable electric artifice. They’re exciting tracks to compare as a two-movement composition.

The Gerogerigegege – >(decrescendo) Final Chapter (Inundow). >(decrescendo) was originally released as a cassette in 2019 and features the enigmatic Japanese noise icon playing ambient hapi drum outside. It’s beautiful, soft, meditative, but lonely and mysterious. The new CD release includes a second disc which presents a deteriorated successor to the first one, burying the hapi drum and captured environment in distortion and soil, leaving nothing but an overamplified shell behind. It’s harsh but empty and contains all the emotions of watching a loved one deliberately self-destruct.

Yan Jun – hongkong (No Rent Records). 9 tracks of buzzing and bumping feedback, piercing tones, electric crunching and sporadic chaos. It’s noisy in sensibilities and ripe with expressionist frustration but favours nuance to pure catharsis, instead letting the electric fury out gradually through soft blasts of precise noise and carefully erupting electronics.

Klara Lewis – Live in Montreal 2018 (Editions Mego). This live performance takes the shape of a long, slow, noisy, triumphant ambient piece that slowly drifts between tape loops, moods and sensibilities. It evokes a cold but dense environment that is exciting to hear develop and mutate, leading to several powerful moments.

Tony Lugo – Synthetic Percussion Music (ETAT). ETAT has been releasing some of the most exciting and extreme electronic music of recent years, and Synthetic Percussion Music is their most intense release yet. It’s entirely sourced from percussion performances, digitally dissected and resynthesized into massive grotesque noise masses. Each track uses different effects and sources, so they all offer a different breed of stereosynthetic ferocity.

https://etat.xyz/release/SyntheticPercussionWorks

Lasse Marhaug & Jérôme Noetinger – Top (Erstwhile Records). Listening to Top is like being transported back in time to a strange Viennese club and hearing an ear-shredding, mind-blowingly bizarre concert, the type you wouldn’t even be sure how to put into words. Both artist bring plenty originality to their performances, but there’s also a nostalgic look back in this tribute to Pita that makes for a chaotic but warm listen.

Jérôme Noetinger – Sur quelques mondes étranges (Gagarin Records). This album collects one-take performances by reel-to-reel maestro Jérôme Noetinger and has him sounding incredibly refined, more exciting as a solo artist than I’ve heard before. There’s an improvised spontaneity to them but they still manage to play out as thematically-rich and complex mini-narratives, each evoking its own uniquely disjointed atmosphere. The highlight is the 18-minute ‘Eine andere magische Stadt’, a slow and dynamic drone piece full of buzzing statics and spinning tapes.

Chiho Oka & Aoi Tagami – The Best Concert Ever by Chiho Oka and Aoi Tagami (Ftarri). The first half is a duo improvisation of abstract voice, processed but melodic guitar, and occasionally explosive laptop sounds. It’s strange yet comfortable, patient yet primal. This doesn’t really reveal itself to be the best concert ever (by Chiho Oka and Aoi Tagami) until the second track, which is a game that has the duo drawing cards to prompt their next song. The result is a playful combination of improvised electronics and soft folk song. It’s awkward and charming in the best of ways – as pleasant and sweet as it is disorienting and harsh.

Patient K – Piss Artist (4iB Records). Since Sutcliffe Jügend “broke up” in 2019, the duo has been starting new projects to advance and diversify their contemporary power electronics sound even further. The songs of Piss Artist are full of industrial rhythms and oppressive distortion, but with a surprising attention to melody. The aesthetic is grotesque and shameful, making the warmest moments feel perverse and the bleakest feel hellish, but there’s a sick, liberated joy in its cathartic self-expression that keeps me coming back to this.

The Rita – Her Shell, The Chute (Scream & Writhe). The Rita is best known as an innovator for the harsh noise wall genre, but over recent years he’s been innovating a new style that’s somehow even more difficult and alienating. It’s a harsh and indulgent mess of clicks and clips, in this case made from “working a Lange XT 130 LV ski boot”. It doesn’t go anywhere, it doesn’t change, it just crackles and crackles and crackles, bridging an aesthetic gap between pure noise wall and Sachiko M. The atmosphere on this one is so cold and bleak though – capturing the sensation of being buried beneath an avalanche or lost in a ski accident perfectly.

Vanessa Rossetto – The Actress (Erstwhile Records). Vanessa Rossetto has been becoming an increasingly significant and exciting name in the field recordings/sound collage world for years, and this is good enough to be the album it was all building up to. Each track is a complex, dynamic, full narrative, rich with memories and ideas. What I find most wonderful about The Actress is how every track feels like it’s based on specific thoughts, feelings and events, but they’re things only the artist properly understands – we as listeners just listen along and find our own interpretations.

Germaine Sijstermans – Betula (elsewhere). Once again, my most listened album of the year comes from elsewhere. The chamber compositions on Betula are soft, lush and sweet, full of sustained tones that delicately hang in the air and harmonize. It makes for such an easy, calming listen, but there’s no shortage of nuanced creativity here – both in composition and performances.

Taku Sugimoto / Cristián Alvear, Santiago Blanco & Nicolás Carrasco – Mada (Modern Concern). Although this is the second realization of Mada that Cristián Alvear has released, there is a shocking difference in realization and aesthetics between the two versions. The new Mada is primarily electronic, with pulsing synthesizers and electronic noises that make the loud moments beautiful, the soft moments surreal and the silent moments uncanny. It’s a bit of a twist on the aesthetics expected from this type of ultraminimal composed music, but it works very well.

Philip Sulidae – Slí Skala (Self-Released). Philip Sulidae’s Bandcamp subscriber series has been a thrill to follow, with 20 releases out since 2021. They’re all based on recent field recordings made in his home of Hobart, Tasmania, with liberal use of EQ, filtering and computer sounds. The result is a fictional Tasmania that’s controlled by Sulidae’s rigid aesthetics, and the releases add together into a two-year document of this fascinating, fake place. Slí Skala has been my favourite of these releases – 4 tracks of gorgeous, strange, soft commotion surrounded in electric and insect hums.

Mark Vernon – A World Behind This World (Persistence of Sound). A World Behind This World is a lot more specific than Time Deferred is – it’s less vibe-heavy, and more focused on twisting and creating environments. The recordings are all made from in and around a sculpture workshop but are presented in an abstracted state, turning the ambiguous factory cacophony into a controlled composition, or an investigation of a fictional world.

Iannis Xenakis – Electroacoustic Works (Karlrecords). This set collects four hours of Xenakis’s electroacoustic and tape works, all remixed and remastered to sound remarkably fresh. The earliest tracks from the 50s already feel otherworldly, and the new mix of Persepolis sounds absolutely huge and cacophonous, but 1978’s La Légende d'Eer is the highlight for me – a surreal masterpiece of sound exploration and mythological abstraction. His late-era computer works are exceptional too – absolutely bizarre, dissonant, ugly, and wonderful.

Sun Yizhou – Ruin (Brachliegen Tapes). Ruin is an album of unpredictable, spastic, raging noise built from pure electricity. It’s full of soft static and aggressive, crunching feedback shouts and bleeding high-end tones. The sounds are raw and the structures are wonderfully impulsive – holding on to textures for as long as it likes and interrupting them with abrupt chaos. With so much clean, refined, pretty improvisation around these days, it’s exciting to hear a musician making such rough, ugly, powerful music.

Keith Prosk

There are so many more wonderful listening or otherwise musical experiences that I will carry forward but these are the recordings released in 2022 to which I compulsively returned most in 2022. I’d also like to acknowledge Bertrand Gauguet, Yannick Guédon, and Carol Robinson’s performances of Éliane Radigue’s Occam pieces on Occam Ocean 4 and DesoDuo’s performances of Eva-Maria Houben’s john muir trails as 2021 releases that shipped out a little later with which I shared quite a bit of time too. And also M.O. Abbott, Microtub, Henrik Nørstebø, and Rage Thormbones’ performance of Catherine Lamb’s inter-spatia, Talea Ensemble’s performance of Sarah Hennies’ Clock Dies, and Zinc & Copper’s performance of Éliane Radigue’s Occam Delta X as 2022 recordings I thoroughly enjoyed but imagine will receive a more normative presentation on the horizon.

Cristián Alvear & Diego Castro - Alvin Lucier: Criss-Cross for Two Electric Guitars (2013) (self-released)

Nick Ashwood, Laura Altman, Jim Denley - Transparent Forms (caterpillar)

mattie barbier - threads (Sofa Music)

Pascal Battus - Cymbale ouverte (Akousis Records)

Frédéric Blondy - Éliane Radigue: Occam XXV (Organ Reframed)

Charles Curtis - Terry Jennings (arr. La Monte Young): Piece for Cello and Saxophone (Saltern)

DesoDuo - Songs for Two (self-released)

Julián Galay, Ángeles Rojas - ɣ (SELLO POSTAL)

Jonathan Heilbron, Andrew Lafkas, Mike Majkowski, Koen Nutters - Bryan Eubanks: for four double basses (INSUB.)

Alma Laprida - ensayos baschet (presses précaires)

John McCowen - Models of Duration (Astral Spirits / Dinzu Artefacts)

Misaki Motofuji - Yagateyamu (Hitorri)

Nabelóse - OMOKENTRO (bohemian drips)

Michiko Ogawa, Sam Dunscombe, Jonathan Heilbron, Catherine Lamb, Rebecca Lane, Lucy Railton, Fredrik Rasten, Sarah Saviet - Junkan (2020) (Marginal Frequency)

Kaori Suzuki - Music for Modified Melodica (Moving Furniture Records)

Masahide Tokunaga - Leverages 杠杆 (Zoomin’ Night)

Zinc & Copper + Leonor Antunes - discrepancies with F.H. (#1#2#3#4#5#6) (Pirelli HangarBicocca)

Thank you so much for sharing time with harmonic series. We hope you have a happy new year.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.78 to $6.21 for November and $0.85 to $4.52 for December. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.