1/25

conversation with Michael Pisaro-Liu; notation from Bryan Eubanks; reviews

Queer Percussion Research Group published its first zine, featuring scores and sharp writings and conversations from contributors Amadeus Julian Regucera, Andy Meyerson, Bent Duo, Bill Solomon, Caitlyn Cawley, JC, Jerry Pergolesi, Jennifer Torrence, Matt LeVeque, Myles McLean, Noah D., Sarah Hennies, ToastMasx x Mascaroni, edited and published by Bill Solomon.

Mark van Tongeren recently published the book Overtone Singing, with ethnomusicological, physical, and practical perspectives.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.85 to $4.52 for December and $1.25 to $3.36 for January. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Gil Sansón: The essay you wrote to deal with the subject of Wandelweiser is very much essential as an introduction, and in it you describe how the composers who are now seen as the main figures of Wandelweiser came to meet each other and realise the potential for musical and social advance within a new relationship between sound and silence, between time perceived and time quantified. I'm particularly interested in how you came to this paradigm before meeting Antoine Beuger or the other founding figures of Wandelweiser, and to what degree the common references (Cage, Wolff, Fluxus, etc.) made evident that there was a group of composers who were mining the same territory, so to speak, without being aware of each other. The question here would be how did you come to be so that your musical interests aligned so harmoniously with these composers from Europe?

Michael Pisaro-Liu: I think it’s one of those things where preparation is only a part of it. I must have been primed a bit by my background. In Chicago I studied with George Flynn (who had been simultaneously part of the uptown and downtown scenes in NY in the 1960s), Ben Johnston (who had worked with Partch and Cage) and Alan Stout (who was a student of Wallingford Riegger and Henry Cowell). I was very inspired by the music of Charles Ives. When I was in my early twenties, we had a group that played Feldman, Wolff, Cage, Haubenstock-Ramati, and so on. So although experimental music was out of fashion in classical music circles in the 80s when I was a student, I was actually never far from it. However it really was out-of-fashion in the US in the 80s and for some time thereafter. The other plus of being in Chicago was that the AACM was there. I loved all of it - Art Ensemble, Braxton, Muhal Richard Abrams, and though he was not in AACM, Cecil Taylor - not that I knew what to do with it as a composer who was pretty far removed from the jazz tradition. (In retrospect it’s obviously foundational to any contemporary conception of experimental music.)

In my first 12 or so years of writing music, I had written in all kinds of different styles, seemingly searching for something. I liked the European avant-garde (especially Ligeti, Lutoslawski and Berio), but it didn’t feel like something I could honestly work with as a composer from the US (and from the midwest at that). Increasingly, and perhaps like the rest of the people in Wandelweiser, I was attempting to find something that spoke a completely different language. In around 1990 or so I put a long silence in a piece, with no clear reason why. There were tentative steps in that direction for a few years in the early ‘90s. I would not say that I'd found the Wandelweiser paradigm yet. It was more like seeing the fin of a shark moving quickly across the water without knowing what was beneath.

The “alignment,” as you call it, felt like it was instantaneous. More or less as soon as I heard Kunsu Shim’s music, and then shortly thereafter, Antoine and Jürg’s - I absolutely knew that was what I had been searching for. They were bolder - especially Antoine. And they seemed to be able to do more with their music in the European environment. Perhaps because Cage, Feldman, Lucier, Wolff and so on were still pretty central to Europe’s conception of the American avant-garde? But for me Kunsu, Antoine and Jürg were miles ahead of that, and lighted the way forward. I stepped on the gas to try to catch up.

GS: You used the term singularity to describe Wandelweiser. I think it's very accurate. An event from which a number of trajectories emerge, that regardless of how far they may stretch from each other they can always be traced back to this singular event. Now more than 20 years after, the Wandelweiser network has grown considerably and the map of the network finds many overlapping vectors encompassing many types of music making, complicating the issue of what is the sound of Wandelweiser to a high degree. At the same time, if we make the analogy to that other singularity (The Big Bang) it was to be expected that some bodies would generate more gravity, one evidence of this being your Gravity Wave label. My question is this: Did you feel in any way limited by the Wandelweiser record label regarding the way you feel your music should be presented, or was there simply a need to express yourself artistically in every aspect of record production? Maybe a mix of factors including these? Your CDs on Wandelweiser seem to have a different attitude compared to the ones on Gravity Wave, in which there are artistic statements that seem to push the limits of what's commonly known as Wandelweiser music, yet at the same time retain the same sensibility. Some of them have a closed form appearance, in that they are fully formed artistic statements and not so much recordings of your scores as finished electroacoustic pieces. It all seems to point at a wish to test personal boundaries in a more controlled editorial environment, completely devoted to a singular vision.

MP-L: The analogy with a singularity (or “event”) is, in my opinion, correct. I refer back to this beginning all the time. My belief that the consequences of this event should be explored and tested to their furthest limits has definitely led me in directions I wouldn’t have anticipated 30 years ago. But it really hasn’t been so calculated. I never thought about what I could or could not release on Wandelweiser, in terms of the actual music. Aside from some practical considerations, including the idea of starting Gravity Wave being suggested by Jon Abbey, with the generous offer that he and Yuko Zama would help me run it. I think it (i.e., GW) turned into something like what you said: an exploration of the recording as a fixed or in some ways, closed, work. For me there’s no getting around that fact, so I thought: why not embrace it? After all, my scored works often continue to deal with openness and indeterminacy, in situations where the creativity of the performer in the moment accounts for so much of what we enjoy about the music. Musical performance in the live situation is like theater, whereas fixed works are like film. So, over time, I’m less interested in using the label to record scored pieces than to explore ideas that come up in a fixed, clearly finite medium. If I were to try to summarize, looking back at the series of 20 discs, and in particular Continuum Unbound and Nature Denatured and Found Again, it has something to do with how a sense of the infinite can be touched in situations where there are clear limits. The formal possibilities for exploring this continue to fascinate me.

The image I have of Wandelweiser is an exploding star-plant, casting embers in just about any direction, and then encouraging these fire-seeds to grow in ways that are conducive to the local environment. There’s something ineffable in the “whatever” of Wandelweiser, as it was and is. I’ve never accepted stylistic descriptions as what it was all about, even if, especially at the beginning, one could have described the similarities between the work of the various composers more easily. Rather than individual works then, it is these collectively explored trajectories in what is still a kind of world or community, that continues to fascinate and inspire me.

GS: The view you describe is the one that feels closer to reality in my encounters with Wandelweiser. If I could summarize it in one simple notion, I would say that it is an invitation, a very open invitation without a goal in sight, but with an inclusiveness that seems to imply a tacit understatement about what Wandelweiser offers, which doesn't need to be explained and the certainty that whatever results from this encounter you will still recognize yourself in it, and that this voluntary rejection of the impulse to define and set limits for this greater collective body of work is, in fact, a big plus that stimulates experimentation. I would also add that there's also an awareness of the lessons of past experiences as ethical guidelines that smartly avoids confrontation and stimulates civilized discussion, which has prevented the typical splintering into subgroups according to ideological or political divides.

My next question has to do with style and form. I've noticed in your work a strong affinity towards the grid, and while thinking deeper about it I've noticed that it is one of the key aspects that has enabled you to retain stylistic consistency when dealing with the very wide array of sound present in your work, from white noise to highly charged with content samples of soul music or location specific field recordings. This makes me wonder, do you work with a continuum between aspects of sound (from fully neutral to highly charged in terms of content, from pure noise to pure tone, and so on) to generate material (and perhaps to ensure dynamic variety) and then decide on the proper length units of each block of the grid? Or does a previous notion already narrow down the possibilities?

MP-L: I think you’ve put that very well and completely agree.

That’s a challenging question! I’d have to say that I do not have just one working method. I’m not working towards a kind of unified theory, and don’t see my work as needing to demonstrate obvious sonic continuity along a single trajectory. It is the ineffable continuities that interest me. Each new piece or project feels like a beginning. Its source is in an impulse that genuinely stirs or disorients me. This can be almost anything. I’m interested in things that I perceive to be outside myself, as things that feel strange or unknown. So a work starts as an encounter with this foreign matter, which could be an untraceable feeling, a sonic disturbance, a speculative idea, the odd sensibility of another musician (or some combination of these) – or a word, a sentence, an image, a wave, a road or a river. Most of the time it takes me a long time to tease out the implications of this impulse. A lot of trial and error. Believe it or not, I’m not interested in formal ideas or musical processes for their own sake. The technical materials have to grow from this impulse, not vice versa. So having said all that, I have to recognize that certain things (like the grid) do come back again and again. Perhaps there is, after all, a deep need to put the chaos of an encounter into some kind of order. But I’m not obsessed with order - in fact I’m more drawn to things that feel errant and unpredictable (in small or large ways) than to things that seem to follow logically. So I guess maybe a grid (or some of the other schemes I’ve used in the past) is a rather simple way to give some kind of order to situations that I will (hopefully) allow to retain a sense of contingent, organic growth and decay. But I feel I’m describing more of my working process than the actual pieces, which in the end somehow all do feel to me like they belong in the same family.

GS: Indeed, your music can be all over the place in stylistic terms, and yet it retains enough characteristics to be recognized as your music. One example is Melody, Silence for solo guitar: very removed from a lot of your music in terms of structure, which is very loose compared to most of your pieces. The chaos you mention seems to get in here by way of odd modulations and voicings that seem to have no other reason than chance or whim, but at the same time you do have a "style" of guitar, it's easily recognizable.

What you say about the spark that lightens a project being something as small as a phrase or a quotation is quite interesting. Your collaboration with Graham Lambkin seems a case in point, it all sprang out of a line from Pierrot lunaire, am I correct? Also, I want to talk about Revolution Shuffle: here the grid is very much in evidence and the effect is that of a colossal mosaic, a giant object to be observed following a type of attention span that Stockhausen would have called moment form, the type of listening that's not looking for development of themes but who's attention is focused on the moment by moment basis of the music. Needless to say, it's your most political work, capturing an urgency and a sense of rage that's uncommon in people's perception of what Wandelweiser music is. Now, people who have been paying attention to the words of Antoine Beuger will not see this piece as an oddity, as he said that for him a piece like Non consumiamo Marx by Luigi Nono is as current today for him as it was when it was released, meaning he doesn't see it as far away or antithetical to what Wandelweiser stands for. In that sense, Revolution Shuffle is, perhaps, not unlike Non consumiamo Marx for the XXI century. In a way, it seems that other pieces of yours prepared the terrain for this one, I'm thinking about Étant donnés, in which you include samples loaded with semantic and cultural content. Is Revolution Shuffle a personal milestone in that sense?

MP-L: “Indeed, your music can be all over the place in stylistic terms, and yet it retains enough characteristics to be recognized as your music. One example is Melody, Silence for solo guitar: very removed from a lot of your music in terms of structure, which is very loose compared to most of your pieces. The chaos you mention seems to get in here by way of odd modulations and voicings that seem to have no other reason than chance or whim, but at the same time you do have a "style" of guitar, it's easily recognizable.”

That’s interesting to hear you say. In fact the piece began as a transcription of an improvisation. The modulations, voices and other odd turns of phrase must connect to my unconscious, deeply buried sense of melody and harmony. My inner ear tells me where to go. In the process of refining the transcription into the piece into the final structures, I tried to preserve the freshness of those choices.

“What you say about the spark that lightens a project being something as small as a phrase or a quotation is quite interesting. Your collaboration with Graham Lambkin seems a case in point, it all sprang out of a line from Pierrot Lunaire, am I correct?”

Actually it was the other way around. Graham and I began working together on the pieces in a different way. I composed and recorded a set of short piano pieces which I sent to him with the idea that he could do whatever he wanted to with them. The pieces I wrote were (in my mind) by an imaginary composer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, perhaps an acquaintance of Schoenberg’s. There was perhaps also a touch of Lovecraft. As our collaboration developed from Graham’s reworking of that music, and with many additions of his own, this character got even stronger. When he asked about the titles I went into the German translation of Albert Giraud’s Pierrot lunaire looking for funny phrases - and of course had always loved that one. For the other titles, there are a couple of the images I just made up (and translated into German) and a couple from Georg Trakl. (So the titles came very much after the fact.)

“Also, I want to talk about Revolution Shuffle: here the grid is very much in evidence and the effect is that of a colossal mosaic, a giant object to be observed following a type of attention span that Stockhausen would have called momente form, the type of listening that's not looking for development of themes but who's attention is focused on the moment by moment basis of the music. Needless to say, it's your most political work, capturing an urgency and a sense of rage that's uncommon in people's perception of what Wandelweiser music is. Now, people who have been paying attention to the words of Antoine Beuger will not see this piece as an oddity, as he said that for him a piece like Non consumiamo Marx by Luigi Nono is as current today for him as it was when it was released, meaning he doesn't see it as far away or antithetical to what Wandelweiser stands for. In that sense, Revolution Shuffle is, perhaps, not unlike Non consumiamo Marx for the XXI century. In a way, it seems that other pieces of yours prepared the terrain for this one, I'm thinking about Étant donnés, in which you include samples loaded with semantic and cultural content. Is Revolution Shuffle a personal milestone in that sense?”

Yes. As must be obvious, my creative imagination is a bit restless. I love venturing into new territory (even if that means approaching “old” territory as if it were new, as is the case with Schwarze Riesenfalter). But my interest in sampling actually goes back pretty far. I made a sampling piece in the early 1990s (before I joined Wandelweiser) that used a lot of punk music (that piece was called The Voter Registration Act). It’s not something I include in my works list now, but it sometimes resurfaces. (Incidentally, in another work I don’t share often anymore, for choir, I also used some of the Paris 1968 texts like those Nono used in Non consumiamo Marx.)

I got the itch to use the technique again in response to Duchamp’s Étant donnés, which I finally saw in Philadelphia in 2013 after only seeing photos of it before. (Photos absolutely do not do justice to the installation.) So the sampling is a bit of a pun on the word “given” and perhaps includes the concept of the readymade in some sense. My disc of the same name was largely built from samples and then fleshed out with recorded additions.

Jon Abbey was pleasantly surprised by the pieces that used Curtis Mayfield samples and asked if I’d consider making a whole disc (for erstwhile) using similar kinds of samples. But I felt ultimately that I should draw on as wide a range of reference as I felt the desire to include. A lot of the work got started in the early part of the pandemic and during the George Floyd protests (which were very strong in LA, as elsewhere). We were living then (as we still are now) though a time when it seemed that something radical needed to change, but in which the means to do this seem blocked or at least unclear. For me it was also a case of summoning the courage to make this feeling a part of a musical piece. How to do that?

So I started thinking about the power of revolutionary movements: how they both express the vitality and passion of an uprising and then, as stories, as legends, as histories, become a reservoir of hope for future movements. (The Paris Commune was a failure as a revolution, but its power to stimulate future revolutionary momentum seems to have been very large.) The piece was my attempt to capture some of the leftist revolutionary spirit, as preserved in sound from a variety of movements across the 20th and 21st centuries. It’s more allusive than specific (though there certainly are a few moments of specificity). There is an undeniable heroism in the radicals of the Civil Rights movement in the US, in the Paris ’68 revolts and the Sunflower Student Movement in Taiwan, and so on. But it’s this elusive “spirit” that I tried to touch in the piece, rather than any particular ideology. (The voices of Lenin, Trotsky and Mandelstam all appear in one section of the piece, for example.) The proximity of leftist political revolt to stirring music is remarkable. But there are lots of other things in there, some cryptic, some personal, some suggestions even. I suppose there’s a lot more I could say, but I’m more interested in the stories that listeners have in hearing the piece, than in my own ideas. But yes, it’s a passion project.

GS: This political dimension of music goes beyond the artistic statement into actual social commitment in your teaching, it seems. CalArts, from what I've heard, is closer in spirit to the Scratch Orchestra than to, say, Juilliard, coming across as utopian in spirit and pragmatic in practice. In that sense, it appears to be a great match for the experimental tradition you're part of. The West Coast approach to teaching arts has a very different attitude to the "sink or swim" ethos of Boston and New York, probably better suited for the brand of experimentalism that your music stands for, which doesn't want to shock or break boundaries but at the same time remains uncompromising in all key aspects. Can you elaborate a bit on the dynamics of the back and forth feedback between teacher and student?

MP-L: CalArts is a lot of things! The year 2000, when I started there, was also the first year of James Tenney (after a long period of his teaching at York University in Toronto). Mort Subotnick, Mark Trayle, Lucky Mosko and Art Jarvinen were all still teaching there, and David Rosenboom was Dean. So I came into a situation where experimental music was already very strong. I was encouraged to teach a class called Experimental Music Workshop (a name I stole from Christian Wolff, with his permission) - which I had started at Northwestern five years before. There are elements of that class (which I still teach) and of other aspects of the school that have something of the Scratch Orchestra spirit.

I have always enjoyed teaching artists. I view my role as being the student of my student. I want them to tell me, to show me and to explain to me what they are doing and why they think they are doing it. In a way I’m teaching them how to teach me. (I try to be a good student too!) As I come to understand their work and ideas better, I reflect my understanding back to them, that is, re-describe it in my own terms and with references to other music, art and even politics, that I think apply. I want us to get to a point where we are able to dive deep into their work and their ideas. My students know that I’m no fan of “corrective” criticism. I do not want to compose their music for them. I’m drawn to what seems to me to be unique, something that only they could think of. My basic philosophy is that an artist grows best by being in a creatively stimulating, challenging, but fundamentally positive and supportive environment.

GS: Young artists, especially in experimental music, need to experiment and thus often fail but come out of it wiser and focused. Your approach seems to encourage this and not advancing an aesthetic agenda with your students as pawns, which is still common practice in many conservatory institutions. I wonder if the competitive nature of so called classical music is behind this, and it must be refreshing to teach music on a one to one basis, working with each student to better formulate questions or helping them to develop their own heuristic tools. Does philosophy play a role here as well? I've noticed an interest in philosophy in your work (we did collaborate on a score that was directly inspired by Deleuze and his notion of the field of immanence), and you have shown interest in thinkers like Deleuze and Badiou, offering interesting insights on the subject in conversation and social media posting. Would you elaborate a bit on the role of philosophy as foundation in your work and general attitude? It seems to me that one of the great maladies of our time is the assumption that philosophy is somehow expendable and a poor career choice, when in fact philosophy is essential in everyday life, and you can see its trace everywhere. In a way I'm somewhat surprised that no one has noticed the relation between Wandelweiser and stoicism, for example.

MP-L: I agree with you that philosophy, in the sense of formulating the premises of thought, is everywhere - and that this is mostly unacknowledged. (We use the concepts without realizing where they come from.) My interest began from that - to probe and also develop the assumptions of my own thinking as best I can, using some of the conceptual tools philosophers have created.

I’m interested in all of it, but my education is largely informal and scattershot. Starting in high school and through college I just read more or less randomly, or by suggestion (Sartre-Camus-Beckett, Benjamin-Adorno, Rorty, Foucault, the Situationists …). I think the genealogy of Deleuze’s interests was the first thing that provided any rigor to my reading, some 30 years ago. It led me to Leibnitz, Spinoza, Bergson, Nietzsche, Foucault, Kant, Hume and so on. Discovering Badiou by the late ‘90s led me in other directions - to Plato, Descartes, Lacan, a bit of Hegel, Marx, and eventually to Meillassoux (one of Badiou’s former students). In the past few years I’ve engaged more seriously with ancient Chinese philosophy - the I Ching and Taoism - in ways that have taken me far beyond anything I would have picked up from Cage. (Francois Jullien was a good guide for some of this.) I spent a lot of time reading Bernard Stieger this summer. Plenty of lesser known writers too, often in conversation with Antoine (who has a knack for finding fascinating, more obscure thinkers): Alexius Meinong, Nelson Goodman, Anne Duformantelle, Vladimir Jankelevitch, John Holloway (this list could go on). I realize it seems eclectic - but perhaps that’s a bit of a luxury in being a non-professional: to not have to resolve the contradictory threads, or rather, to allow the contradictions to continue to generate meaningful thought. But I continue to believe that somewhere between Deleuze and Badiou there is a real theory of experimental music.

Throughout I’ve also been looking for ways that these concepts can help in my work. And I think they help a lot! Sometimes it's hard to say exactly how they help though. Maybe it’s the mental exercise ... But sometimes I have the feeling that there are more direct connections between philosophical concepts (like Immanence, as you mentioned) and what I do, and this keeps me on track. Reading Spinoza is a piece that deals directly with a philosophical text and what I considered to be the immanent formal methods that would follow from it. But perhaps the best example is in Continuum Unbound, where thoughts about the limits to human understanding from direct experience (Meillassoux’s idea of the correlation) led to a set of hypotheticals about how to construct a music beyond conventional models of nature.

But it’s also good to know where conscious thought leaves off. A lot of what I do as a musician goes by intuition, and somehow the exposure to rigorous thinking also has the effect of making me know when to trust my instincts.

You might be right about the connection between Wandelweiser and Stoicism, but personally I haven’t spent much time reading them.

GS: I'm a lot like you in that I felt that I would have do develop my own relationship towards the classics, and in fact I trusted my instincts and avoided Hegel for a long time (still find that his system is much too compromised by Christianism and metaphysics, and especially by the insistence on the tree as general model of organization, which simply I can no longer relate to after being exposed to the rhizome; there are no trees independent from each other and we have learned that they do in fact form a rhizome in the mycelium network that communicates between the trees underground), though now that I approach him with this caveat I find much to explain the current world, in particular the limitations of the world, that likely spring from this incomplete picture that reveals a mirage that fools the observer. To give you one example, Anti-Oedipus came into my life by chance, the girlfriend of a friend handed me her well worn copy, which I read by turns, doing exactly what Deleuze and Guattari suggested in A Thousand Plateaus instinctively. Of course I couldn't say that I understood everything at first, but I distinctly remember feeling the gears in my mind set in motion due to the stimulus of the book. Deleuze was also my introduction to Hume, Bergson and Spinoza (his book on Spinoza is particularly revealing and illuminating), and I already had a hold on Nietzsche and his view of philosophical problems as psychological problems has been with me ever since. I don't think it's as easy as to cite a philosopher in the title of a piece in order to establish a connection, but at the same time my instinct detects a lot of Spinoza in Antoine Beuger's music (or the influence of Morandi on Jürg Frey's music). As for your work, the field of immanence was crucial when engaging with your Continuum Unbound, that can give the impression of several maps superimposed on top of each other.

And there's another text that I find essential to understand what Wandelweiser is about, Debord's The Society of the Spectacle. In Wandelweiser music I see a conscious effort to avoid the commodification that can turn even silence into part of the spectacle. There's no active resistance against the spectacle (stoicism) but also there's something of a Bartleby stance that ensures the music effectively resists the commodification that other musics superficially related have experienced. There's also the type of joy in creation as an affirmative notion, not as a reaction against the world but as a way to see what are the limits, a very Nietzschean idea.

This also can be found in the formal aspect. If, say, sonata form is perfectly suited to express Hegelian ideas, then new forms of organizing sound should exemplify the concepts that have been proposed as alternative. Sonata form suits the tree model very well, but makes little sense as part of a rhizome. At the same time, and this is something I discussed with Jürg, music history seems to exert a lot of gravitational pull on occasion, and this could lead to very interesting connections and actualization of paradigms, like you did with the music of Couperin. An essence seems present, only operating in a context far different from Couperin's time.

MP-L: I think we take bits of language, concepts, and then of course, images and sounds and reassemble them in our brains. There’s a plasticity (to reference Hegel and Malabou) in this process that I trust. We’re recreating a world in our own thoughts and actions. There are embedded structures there (the concepts that we learn that do tend to structure our thinking to some extent), but there’s also much room for creative assemblage if one works at it. So the references are re-embedded hopefully in new contexts and more importantly, in new works. For me there’s more Antoine than Spinoza (in his Spinoza pieces) and more Jürg than Morandi in his work. But the satellites (i.e., references) are helpful in extending my relationship with their work(s).

Funny that you mentioned it: I just rewatched The Society of the Spectacle this summer. (I watched all the films by Debord I could find, actually - an incredible body of work.)

It’s especially the case with “early” Wandelweiser that it attempts to derail the spectacle, I agree with that. Maybe in a pretty radical way. (To some extent though all critical or underground, experimental, whatever we want to call it, art does that, don’t you think?) In any case, from my experience there was (or needed to be) active resistance to the spectacle. But also in early Wandelweiser, I felt there was a risk of “monumentalizing” silence, which would amount to turning it back into a “spectacle” - something impenetrable, rather than something one actively absorbed or actively engaged. But as you indicate, it’s not simple and maybe silence is one of the best examples of a true contradiction. Perhaps there were these kinds of differences “within” Wandelweiser. What silence as material started to reveal to me was the “transparent” layers of reality, which I see (actually, hear) as invisible curtains, arrayed one after another in any situation. There is something labyrinthine in this silence which I feel like I’ve been exploring ever since. It’s not exactly full, this emptiness, but it is also not the “void” (for me at least).

For any of us who studied music (which I guess is any musician), the genealogy of what we resonated with will play a role. These forces are basically always there, and there’s no point in trying to escape them. (This aspect of European musical modernism of the mid-20th century, the idea that there’s a need to escape from the past, has never appealed to me. I think because I do not view time as linear and don’t believe in progress, at least in the 20th century modernist orientation within the industrial-capitalist-technological landscape.) There’s no repetition in art, really. The fascinating question to me, is rather, what can happen when some part of that genealogy is activated. This is contingent, woven into our lives, as we all know. In Barricades, for example, it was the inclusion of Les Barricades Mystérieuses amongst the pieces that Shira Legmann sent me from her repertoire, that brought that era (and that music) back alive to me. I had played the piece very often on guitar when I was first studying. It, along with the preludes of Villa-Lobos and the transcriptions of the Satie Gymnopédies, were my favorite guitar pieces when I started learning classical in ca. 1976 or so. The ornamentation in the French Baroque always fascinated me - and in some way connected to the way I had learned and understood jazz (where “solos” ornament harmony and/or melody). But also, as I’ve come to realize since, this music wanders. It’s not obsessed with recapitulation (which drives me crazy sometimes in Germanic music of the Classic period). I think this has always been somewhere in my aesthetic interests, but not so conscious.

When Greg Stuart and I were working on side by side last year, he sent me a wonderful article by Susan McClary, where she discusses, amongst other things, Jean Henry D’Anglebert’s Tombeau de Mr de Chambonnières from 1689 (“Temporality and Ideology: Qualities of Motion in Seventeenth-Century French Music”). She’s interested in “absorption” or, as she calls it "a quality of stillness in which consciousness hovers suspended outside linear time.” Sounds like Wandelweiser, doesn’t it? Indirectly, through a totally different era, she discuss something that I could immediately relate to the work I was doing with Greg at the time, but also back to pieces like Barricades, or stem flower root or a lot of the music I love by Jürg, Antoine, Anastassis Philippakopoulos, Walter Marchetti, Satie, Cage’s Cheap Imitation, and so on. I think the word is really just “melody.” In an interview somewhere, Christian Wolff says (something like) any succession of events becomes melody once your ears find the continuity in it (which is basically always there to find). I take that to mean the continuity (in music) takes care of itself. The obsession with “unity” is misplaced - because, for one thing, in the Deleuzian/Spinozan universe it’s already there (univocality). But also, not to put too sharp a point on it, it’s boring. The embrace of the contingent, the multiple, the monadology, the paths with simultaneously infinite directions is so much more interesting.

I don’t know how related this is, but I love the tendency of the late variations of Beethoven to spiral out of control. His mind is so fecund that he can’t reign the invention in. The Grosse Fuge is the paradigmatic example: it draws ever widening circles for over 500 bars, and then, perhaps realizing there was no way to finish what he started he writes, with an increasingly frantic intensity, over 200 bars of final cadence. It’s hilarious. (At the end of Embryons desseches I’m sure that Satie is parodying Germanic cadential mania with his “Cadence obligée”.) You need herbicide to stop the rhizome from spreading.

GS: Funny you mention late Beethoven, the Grosse Fugue and the Diabelli variations are never far away from my mind, the latter being a treatise on variation form of sorts and the former this almost fractal development that threatens to derail the music with its complexity, like magma erupting, only with almost mathematical logic, one gets the feeling that the composer is riding a tiger. Also, that insight from Wolff about any sequence of sounds becoming melody once repeated has always struck me as spot on. Even if there's no pitch involved the ear will treat some sounds as a tonic, so to speak. Wolff was the most Webernian of the New York School in many ways, it's probable that the way Webern explored the klangfarben melody led him to extrapolate this notion beyond pitch, focusing on timbre, though I feel this has more to do with the act of listening that with any theoretical certainty.

What you say about the natural impulse of capitalism to conquer new territory in relation to the silence in Wandelweiser is quite interesting. There was an attempt to engulf it, but silence, at least the inquiry into silence that characterized early Wandelweiser proved to be an actual limit to capital expansion in the spectacular sense. It can't even be an adversary to capitalism in the sense that it doesn't have an interest in managing expansion and it's seemingly content with doing its own thing at its own pace, happy to play for an audience of one.

It does seem absurd, this idea of progress like a straight line pointing up into the future, right? I am quite invested in the music avant-garde of the second half of the XX century but a lot of it is a cautionary tale for me, with a nasty tendency to throw the baby along with the bath water. And yet I feel that music took giant leaps during that era and to dismiss the many lessons (and fantastic music) of the era is also throwing the baby with the water, to sweep it under the rug and pretend it didn't happen. With so much revisionism in our time I don't think we can afford to paint this period with a large brush. We simply have no more time for the type of agogic of the era, with the dialectical scaffolding so overemphasized that sounds so forced today, but all the new sounds and processes are still ripe for exploration. I mean, you just can't write a piece like Gruppen in 2023, but many timbres and sounds from the piece can still, moments that seem to exist without the need to fit a grand design, sometimes these isolated moments are the key to open a box that used to be hermetic before. After all, when Mozart studied the fugues of J.S. Bach he took what he thought he could use and discarded the rest, this dialogue between composers outside of time has always been there as one of the things that nurture tradition. I often see it in terms of gravity and physics: if you swim against the main current you will spend your energy quickly; if you swim against the current but near the borders, where the current is less strong, you will have a better chance of beating the odds. Applied to music history, this sort of entails a shift in emphasis from the vertical to the horizontal, or even the plane of immanence, with all these figures from the past existing at a more or less levelled plane, at least with regard to this dialogue between composers of different ages, like that feeling of absence Feldman felt with Schubert, the way he worded it, "Schubert leaving me", it's very revealing of his non hierarchical relation to music history.

My last question has to do with improvisation. For a composer improvisation can be liberating, freeing one from the need to control the outcome and also having the function of testing materials in a live setting or discovering them in the act of improvising. It's also interesting to see how flexible the personal heuristic can be in different contexts. It also allows composers to relate to each other musically without micromanaging things and make music in a more instinctive way. I'm thinking of the album you made with Wolff: it doesn't sound like any of the two is trying to make a point, though there are times in which one is content simply listening to the other. There's also this inherent contradiction to releasing documents of improvisation, divorced from "the room", to paraphrase Keith Rowe, where repeated listening allows the listener the chance to contextualize the sound that the actual performers are unable to do while making the music. At the same time we have the example of the cinema of Abbas Kiarostami, that expects the viewer to complete the picture using one's own imagination and engagement. Does this dialogue between improvisation and composition play a role in your mind when thinking about music? I don't mean it in the dialectical sense, mind you.

MP-L: I also love a lot of the music of what we used to call the “Post-War European Avant-Garde”, Gruppen included. Since I was educated in that era, I think I’m responding more to (what I perceived as) the ideology of that music than the actual music. In terms of the actual music it’s nice now to be able to pick and choose and see it in a broader perspective. I still enjoy a few pieces from the central figures, but spend more of my time at the edges of that (post-)serial dream (and still happily play Xenakis, Ustvolskaya, Messiaen, and Parmegiani in particular). Last year during the height of Covid, I felt the need to hear Roberto Gerhard’s The Plague again – it is fantastic. As we discussed, Nono’s music of his Communist era is still very interesting (at this moment I’d much rather hear that than anything by Berio). Also fascinating, for example, that Shostakovich was still composing through some of that period (and, following Keith, I still listen to his music frequently). Not to mention Stravinsky’s great serial music of that era (Agon, Threni, Requiem Canticles.). One doesn’t have to choose between X-Ray Spex and Matthias Spahlinger, fortunately. Also the reflections of that avant-garde in the US were way less interesting than their European inspirations. Contemporary (post-War) “Classical” music in the US in the post-War era is pretty much a wasteland in my book. Thankfully, experimental music in all of its forms was exploding in that period and that has kept me and a lot of other people busy.

I’ve been thinking that not only is the improvisation-composition dyad not dialectical, to me these two terms seem more and more inadequate as the only choices we seem to have. It’s like there is a dimension missing, with points off that particular chart. Lately I’ve been thinking that Deleuze’s Plane of Immanence is a much better way to conceptualize this space - infinite arrays of points, mostly invisible, but scattered in all directions. We only recognize a point when we are on it or pass by it on a particular trajectory (“line of flight”). In the sequence of thought and action that is experimentation, you put your marker down somewhere that appears to you in that moment to be compelling. It is often hard to say why. Maybe some invisible object (in another dimension?) has crossed your path and flashed an infinitesimal light on the situation (i.e., situation being what Keith calls "the room”). What speaks to me now in this place? Sometimes that now is “the time Christian and I have to make music together.” Sometimes that now is "however long it takes to write a piece for these musicians.” There is a logic, and I am actually trying to follow it, but also realize it will be seen mostly in retrospect.

We are looking for processes that keep us engaged, especially now when it seems like we’re constantly being told to live with diminished or even no expectations for the future. (John Holloway’s new book Hope in Hopeless Times speaks to this.) We’ve seen only the smallest bit of what’s “out there”, and therefore need whatever tools we can find to poke and probe at the invisible, inaudible things right next to us, until the disturbance this makes leads us to discover that there’s something else there.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

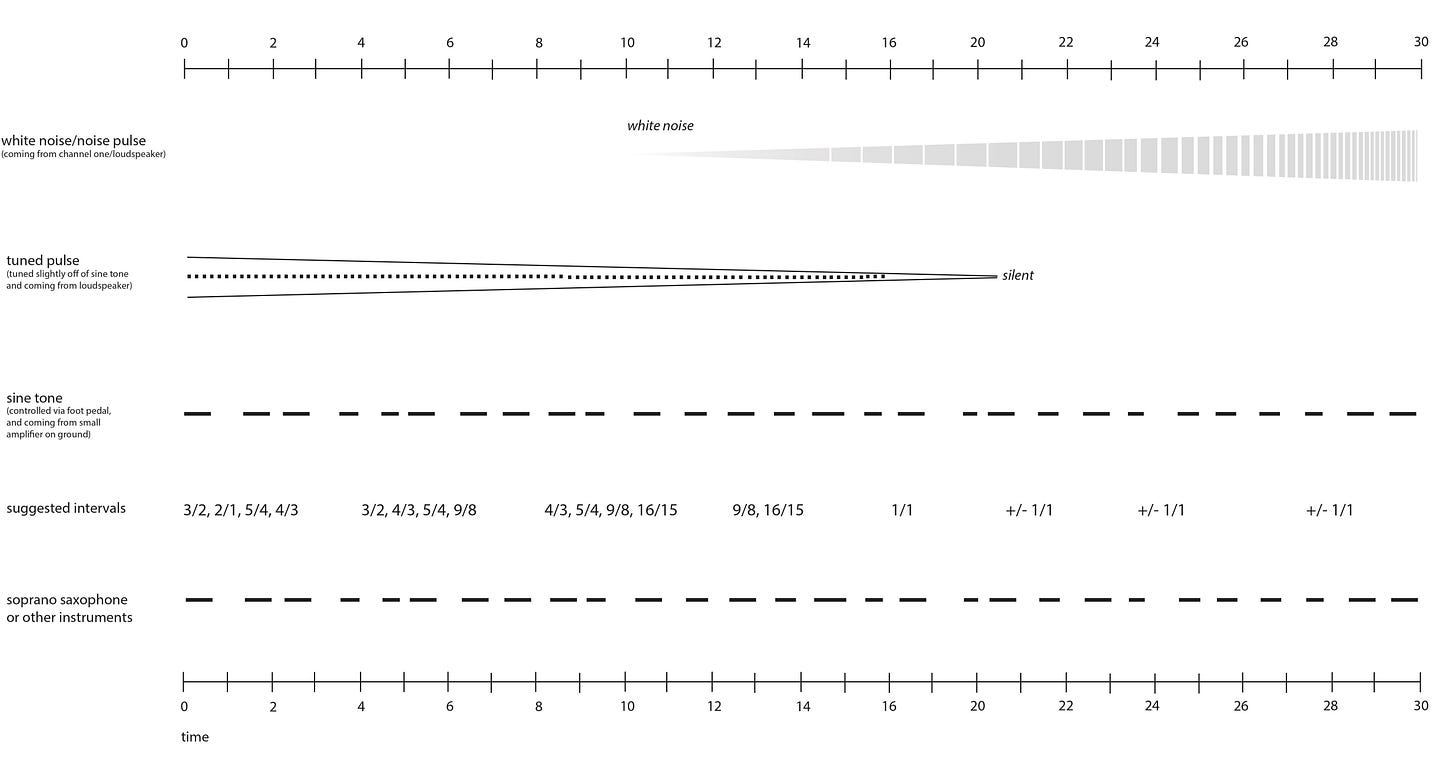

Bryan Eubanks - Spectral Pattern (2012/2013)

Bryan Eubanks is a composer, interpreter, improviser who develops his work through solo and collaborative contexts and plays soprano saxophone, computers, and other (often homemade) electronics. Some recurring collaborators include: Don Brown, Joe Foster, and Dan Reynolds; Todd Capp and Andrew Lafkas as Ocean’s Roar; and fellow Sacred Realism artists Lafkas, Catherine Lamb, Rebecca Lane, and Xavier Lopez. Recent releases include: for four double basses, performed by Jonathan Heilbron, Mike Majkowski, Lafkas, and Koen Nutters; Natural Realms with Lopez; and Lamb’s Prisma Interius IV, performed with Lamb and Lane.

Spectral Pattern is a 2012/2013 composition for soprano saxophone and/or other instruments, tuned pulse, sine tone, and white noise, an open number of players, and a 30’ duration. An aphorism introduces the score:

transformation in time

time in transformation

transformation is time

time is transformation

The score includes a description and diagram of the set up outlining the custom software and equipment that generates the sine tone, tuned pulse, and noise as well as their spatial relations with the performer, with notes that sounds should blend and volume should not be so loud as to distort sounds. Plain instructions detail the limits of sine tone and pitch behaviors the performer may choose relative to each other and to the determined behaviors of tuned pulse and noise. There is an explicit goal of modulating the noise with beating phenomena from sine tone and instrument harmonic interactions, whose periodicity should approach the 5Hz periodicity of the noise towards the end of the performance. A diagram references relations along an absolute timeline, including the development of noise towards a 5Hz pulse, the fading behaviors of tuned pulse and noise, the simultaneous sounding of sine tone and instruments, and the narrowing intervals of instrumental pitch towards their dynamic equilibrium with the sine tone. Spectral Pattern is one of the inspirations cited for Lamb’s Pulse / Shade.

Plain language, supplementary diagrammatic reinforcement, and even suggestions for pitch intervals and sounding placement within minutes focus the performer on the task at hand, the intense concentration required to cultivate precise beating behaviors. The transformation of the noise at the end towards the same periodicity as the tuned pulse at the beginning, as well as an untethering from unison after 15’, suggests a cyclicity on a larger scale than the 30’ duration that might color interpretations. A reading of the aphorism might too, its mirrored balance reflecting the relativity and interdependence inherent in the piece and the synonymity of time as a measure of spatial change, its use of in/is drawing attention towards the spatial relations and states of being upon which the music might hinge, and perhaps its four lines could be tied to its four elements of noise, tuned pulse, sine tone, and instrument. In some way the aphorism, instructions, and diagram are shades of the same information that overlay to convey the color of the piece. The interpretation below is realized alongside Johnny Chang and Lamb on violas.

reviews

Julián Galay - Eine Stadt, Ein Haus (presses précaires, 2022)

Julián Galay realizes two directions from Craig Pedersen with recordings, tuning forks, and sine tones on the 24’ Eine Stadt, Ein Haus.

In the city sines swell with rail squeals stuttering while braking as waves undulate, in anticipation, in synchronicity, in response, mimicking a machinic rhythm in juxtaposition to the natural accidentals of children playing and birds singing. In the house tapped tuning forks and sine tones appear alone, sonorous resonance seemingly free from the contingencies of the environment. But the sustain and stability of sines and tuning forks flow according to the container of the room with clarity and carry the subtle ripples of the moment more plainly than most instruments so to see time as a function of space, music as a function of place. One searches for an accord in relation to the environment; one recognizes the tacit presence of the space in the sound necessarily. That the accord was always there.

- Keith Prosk

Alma Laprida - ensayos baschet (presses précaires, 2022)

Alma Laprida plays seven solos for cristal baschet on the 26’ ensayos baschet.

The recording captures mass chatter reverberating in what appears through a kind of dulled distance to be a large hardwalled space, with intermittent elevator beeping and phone ringing. The subaqueous moo of this lost instrument’s glass material massaged with wet hands a sort of ghost among these living in its glowing resonance, haunting repetition, and cadential suspension. Subtle intuitive tone shifts yield dramatic expansive effects in the amassing of waves in between soundings bounced back from the wall and back again or in a splayed spectra of sound responding to changes in speed and pressure of touch. Less through progression or propulsion than a stubborn stasis its sound blooms in the substrate of this location physically and in spirit.

- Keith Prosk

Ángeles Rojas - breathe into the forest, into the bird, into the song (Sawyer Editions, 2023)

Julián Galay, Guido Kohn, Gustavo Obligado, Ángeles Rojas, Sofia Salvo, and Emiliano Salvatore perform a Rojas composition for open ensemble with tuning forks, cello, alto saxophone, shruti box, baritone saxophone, and electric guitar on the 38’ breathe into the forest, into the bird, into the song.

Nasal shruti sounds rippling strata in infinite sustain as a springboard for the contrapuntal periodicities of other instruments in durational soundings creating a turbulent shear of sound at these instruments’ confluence whose many timbres blur together through overlapping relationships in the calm thrum of breath and beat. They overlay for more activity in sensations of impossible extension and expansion eddying and ebbing, their gossamer harmonics dancing in the open air of the forest. Many and one and long and longer, off the shelf the body can’t discern the difference between the surface and the tsunami. It ends with breathy bowing in breathing cadences sounding the movement of the cathedral of the ribs, with the sighing subtones of saxophone, with the electric pulse that recalls the breath the beating heart requires. A living music in its motifs and the lives of harmonics it cultivates to move within their own wills.

- Keith Prosk

Masahide Tokunaga - Masahide Tokunaga (hitorri, 2022)

Masahide Tokunaga performs a composition with Fumi Endo on piano and Tomoki Tai on viola da gamba and two alto saxophone solos on this 57’ eponymous record.

In the solos sustained tones smooth as sines rise and subside in doppler alternations that complement and weave with overtone oscillations. In “Observer” the domed decay of a single struck piano note and frictional swells of viola da gamba arrange in slow spacious overlapping relationships with the long tones of alto. The tenuous interactions of individual overtones occasionally fishtail through as the performers appear to play with how the shape and color of tone changes with the shifting relative locations of soundings. The observation of harmonic shape and color in relation to location lends a new lens on the solos, to try to hear how adjacent morphologies affect the perceptions of their neighbors, how these sort of wave behaviors and parameters relate to those that illuminate the interactions of the trio.

- Keith Prosk

Various - PP-01 (Party Perfect!!!, 2022)

The debut release from new Chicago/Queens based computer music label Party Perfect!!! feels like the modern, digital equivalent of an independent music zine, one with some tapes or cdrs from local artists and bands. The release includes four albums that span different corners of contemporary electronic music as well as a lengthy, quirkily-formatted pdf including discussions on the music and shared recipes. A physical copy does exist – but it’s just of the booklet, not the music.

Aesthetically there is not so much to tie together the four albums that make up PP-01, except for occupying a shared, uncanny middle-ground between academic coldness and expressive abstraction. They’re rich with complexity both in their compositions and sounds, but never come off as impersonal – there’s so much curiosity, style, feeling, fury, fascination and psychoacoustic excitement to be heard in these pieces.

Each of the four albums included in PP-01 is strong in its own way, they all have their own ideas and vibes to them. They’re worth hearing on their own, but come together like a joyous meeting between a group of people with different but complementary personalities – it’s a perfect party!!!

Michelle Lou – Untitled

The first word that comes to mind when I hear or think about Michelle Lou’s Untitled is ‘violence’. The sounds are aggressive and bombastic but it goes beyond that. Computer tones pulse, shake and contort in stereo, distorting and tearing at each other in unexpected rhythms. The thick, distorted haze doesn’t let up, it’s a constant assault, a violence that won’t go away.

Untitled is gleefully violent towards its listeners. The album opens with thick, speaker-blowing pulses of over-distorted dread, so compressed that even the soft, bassy moments between pulses carry explosive weight. All Night Long introduces a high-pitched sine tone that becomes increasingly uncomfortable on the ears the longer it stagnates. The screeching rhythms of No you’re not dreaming are nightmarish and The End of the World sounds like a proper doomsday alarm that builds into electric apocalypse. It’s a harsh, disorienting, demanding listen to say the least.

A substantial amount of the violence of Untitled is also directed inwards. Through excessive use of distortion and digital clipping, self-destruction becomes one of the album’s major themes and instruments. In very practical ways we can hear electric frequencies combat each other here, or hear programmed music fail to be properly rendered as its crushed beneath its own amplitude. It’s exciting how, while obliterating certain sonic traits that were planned and composed, the clipping both expresses subtle traits that were hidden within those sounds as well as creates new ones – be it repetitive clicks, digital cracks, immersive fuzz or ultrahigh (or ultralow) pressures.

Through the sequencing and indulgence in clipped sound comes some comfort. Catharsis is healthy, it’s even kind of fun. I’m not sure why Michelle Lou decided to make such an angry work here – perhaps it’s a reaction to something external or a reflection of something internal. Either way, Untitled is a massively compelling and affecting album that manages to use the computer in an expressive, heartfelt and genuinely experimental way.

Stefan Maier – The Arranger (Live at HKW)

The Arranger is a live performance for modular synthesizer, machine listening software, sound system and radio-transmission headsets. It’s beautiful, psychedelic and technically precise. High-pitched drones, deep throbs, soft statics and careful clicks grow, pulse and flow through each other in a manner that feels meticulously engineered to stay engaging. Saying “to stay engaging” even feels like undermining what The Arranger accomplishes – it casts binaural hooks into my ears with its opening frequencies that aren’t even momentarily loosened until it’s finished.

It’s all a bit of a charade though. Stefan Maier did compose original music for The Arranger, but much of what we hear is a computer reading and rendering it, trying to understand and reproduce this very precise digital music. And that’s of course, somewhat, a failure. It results in indeterminate attempts at recreation, the genesis of sounds that are similar but not-quite-identical to the planned sounds, making the performance not as tightly-controlled as it initially seems.

A computer is able to parse and create sounds, but what it fails to do is understand the aesthetics or reason behind them, making the music it produces hollow and meaningless. It’s like writing out a sentence with letters from a language you don’t understand – the shapes are there, but it doesn’t mean anything. So the computer may be singing an empty language, but something exciting that happens is that, largely through its own imperfections, the computer manages to find its own aesthetics. There’s certain swirling sounds and chaotic progressions that feel emblematic of the machine learning synthesizer, this becomes clearer as it reads and interprets more information and we hear and perceive more of its sounds. Listening to these computer aesthetics for long enough might even bring one to wonder if the computer could have its own personality – perhaps a trivial question.

I’ve heard this piece a few times now and it’s been very difficult for me to determine which of these contrasted sounds were already presented in Stefan Maier’s composition and which were added by machine synthesis. It does feel like a work of two personalities that constantly butt heads, but it all meshes together into a single, extremely immersive, digital haze. By the time it’s over and the haze lifts it’s almost unbelievable how much sonic ground the performance has covered.

The Arranger comes in two forms – a loudspeaker diffusion and a headphone diffusion. Rather than them being different mixes of the same material, the headphone diffusion is a completely original machine resynthesis of the loudspeaker diffusion – another computer-rendered revision of music made from computer-rendered revisions. It’s a new product that resembles the original work near-perfectly in waveform and spectrogram, but differentiates entirely in timber and sensation, making it worthwhile as both a practical and a conceptual addition to the album.

Michael Flora – Emergent Spectra

Emergent Spectra is both the most direct and the most puzzling of the four albums included in PP-01. The sonic material is confounding and abstract, and the tracks last just enough to thoroughly explore their sound system. It’s quick and vigorous in its execution of ideas.

The first half of this album is comprised of the 6 short Emergent Spectra tracks that all sound like sonic excavations of single concepts: On 001 it’s densely layered bassy tones which activate and deactivate to create shifting dissonances, on 002 it’s rapid-paced stereophonic synthesis, on 003 it’s the pairing of high and low pure tones, on 004 it’s crunching binaural noise, on 005 it’s growing high-pitch frequencies, and on 006 it’s a compressed, swirling digital sound blob of ascending and descending synthesis.

Emergent Spectra could be looked as a study of different types of synthesis or an exploration of different styles of computer music, but it’s also very interested in the psychological and physical effects on the listener of the sounds it’s making. Some of these tracks are completely intoxicating and surreal, Emergent Spectra 001 particularly makes my head swirl. Others make me feel anxiety and claustrophobia, making their short durations feel long, such as 002 and 006. 003 achieves an awkward state of pulsating bliss while 005 elevates me into trebly ecstasy. I’m sure the effects of the music can vary from listener to listener, but that’s part of what makes these psychoacoustic experiments interesting – they present entirely abstract sonic material which has been specifically engineered to work as a physical stimulus for the listener, rather than just something to hear and feel, and the listener’s listening conditions and body biases can play a large role in the effects that that stimulus rouses.

The second half of the album is a single track titled Folded Spectra, which combines a lot of the ideas present in the first 6 tracks into a more linear, captivating composition. It’s exciting to hear these sounds given more space to develop and grow, such as the tones of the first half which are locked in a state of constant ascent, or the sustained insect frequencies, harmonized drones and ripping static noise of the second half. Again the track is indebted to the effects of its sounds, but this time it runs through a range of sensations and feelings that is far too wide to describe.

Other Plastics – almost leisure

Other Plastics is the duo of Hunter Brown and Dominic Coles. It’s the most varied of the four albums that make up PP-01, starting fully digital before moving towards field recorded material and finally a stunning hybrid.

pt1 is soft and beautiful. Computer textures open and close, click and clack, and delicately float around in time and space. Despite their sharpness and unpredictability, they’re seldom harsh – it’s a carefully controlled chaos. Empty space accentuates the musical sequences and surrounds them like picture frames. The hard cuts between sound and silence are like a temporal lapse while the computer considers its next move, the sonic equivalent of browsing the web with spotty internet. It’s hard to detect a logic to the piece’s progression, but there’s something natural about it, like looking at a shuffled Rubik’s Cube that shows all it’s colours on one face.

pt2 is a recording of a party. It starts with the interior, with a conversation about media. It feels equally voyeuristic and comfortable. As the track goes along it starts to cut itself up and become abstract. Sounds filter, accelerate, repeat and shuffle around in stereo. Conversations cut off and pick back up, voices enter and exit – it’s a heavily fragmented party, like the whole night was thrown into a technological black hole and this 8-minute remembering of it was spit out. There’s a clear aesthetic to the sequencing too, a surreal fascination in the scrambling and processing of its sounds, giving it a vibe that’s surprisingly similar to pt1.

pt3 begins with environmental sounds – the low-end sounds of a distant but living city paired with the high-end sounds of numerous singing insects. Natural rhythms are found in the music that flows out from the city – or is that sound computer-generated? Increasingly clear digital sounds enter the mix and intermingle with the acoustic ones. They combine and mutate each other, gradually creating a climate where the computer world and the real world’s sounds can co-exist as elements of the same system.

Despite each track featuring its own ideas and palette, they fit together comfortably. An aesthetic line is tied between computer music and field recording, and they’re held close enough to make the difference feel insignificant. It could be argued that what’s displayed here is that digital sounds are alive, or that real sounds are artificial, or that both share the same murky middle-territory. Either way, the music present on almost leisure is as beautiful as it is hypnotic.

–

Something admirable about the artists on PP-01 is how they deal with and situate themselves within the history of computer music. On the topic of stochastic synthesis, which is often considered old-hat as Iannis Xenakis was using it decades ago, Michael Flora rivals this notion by stating that guitars have been used for centuries and still are. The truth is that, as far as genres go, computer music is a young one.

The objective of these computer musicians isn’t necessarily to innovate or to push new ground, it’s to express something with these tools and styles that already exist. It’s not about making music that Xenakis couldn’t have made 30 years ago, it’s about making music that Xenakis wouldn’t have made, because as abstract as these computer pieces are they are absolutely indebted to their composer’s individual attitudes and personalities. There’s still so much to try, to explore, to hear. That’s why these four albums all manage to excite in entirely different ways despite occupying the same genre and using the same tools.

PP-01 is a very impressive, creative and inspiring release, both in it’s music and in the manner it was released. It rests on the current cutting-edge of electronic music, but feels sentimental and personal rather than just challenging and clever. All of these albums have been enjoyable to revisit, both on speakers and headphones, and I am very much looking forward to hearing what Party Perfect!!! releases into the future.

- Connor Kurtz

Zheng Hao - Harmonium (Hard Return, 2022)

Zheng Hao performs five scenarios for two contact microphones and two harmonicas in C major and B flat major on the 18’ Harmonium.

At the edge of cacophony at the limit of control a digest of feedback modulation behavior tuned to the receptive and sensitive clang of harmonica metal bodies and metal reeds. Soft sinusoidal squeals break silence. The twitch of fingers just overcoming friction an abrupt enough shift to wake the system in whistles and coos. The slow undulations of a low hum that could fall into clicking without a moment’s notice. Stridulatory honk calmed into a whirring singing. The imagined moans of manatees and a squeaking closer to what they really voice. The care required of the body reflected in slow speed and sufficient space conveys a tenderness no matter how wild the sound and can cultivate complexly braided deltas of branching harmonic behaviors in between tone transitions, sounding the spectral gradient between two things.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for sharing time with harmonic series.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $0.85 to $4.52 for December and $1.25 to $3.36 for January. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.