New Recordedness interviews are available, featuring: Jozef Dumoulin in conversation with Flin van Hemmen; Luciano Maggiore with Nick Hoffman; Matt Robidoux with Yutaka Hirose; Kenny Warren with Joanna Mattrey; Frantz Loriot with Silvia Tarozzi & Deborah Walker; and Frantz Loriot with Theresa Wong.

MUSEXPLAT continues its interview series featuring Maxi Mas, Emi Bahamonde Noriega, and other contributors in conversation with Ana G. Gamboa, Alma Laprida, Daniel Bruno, and several others.

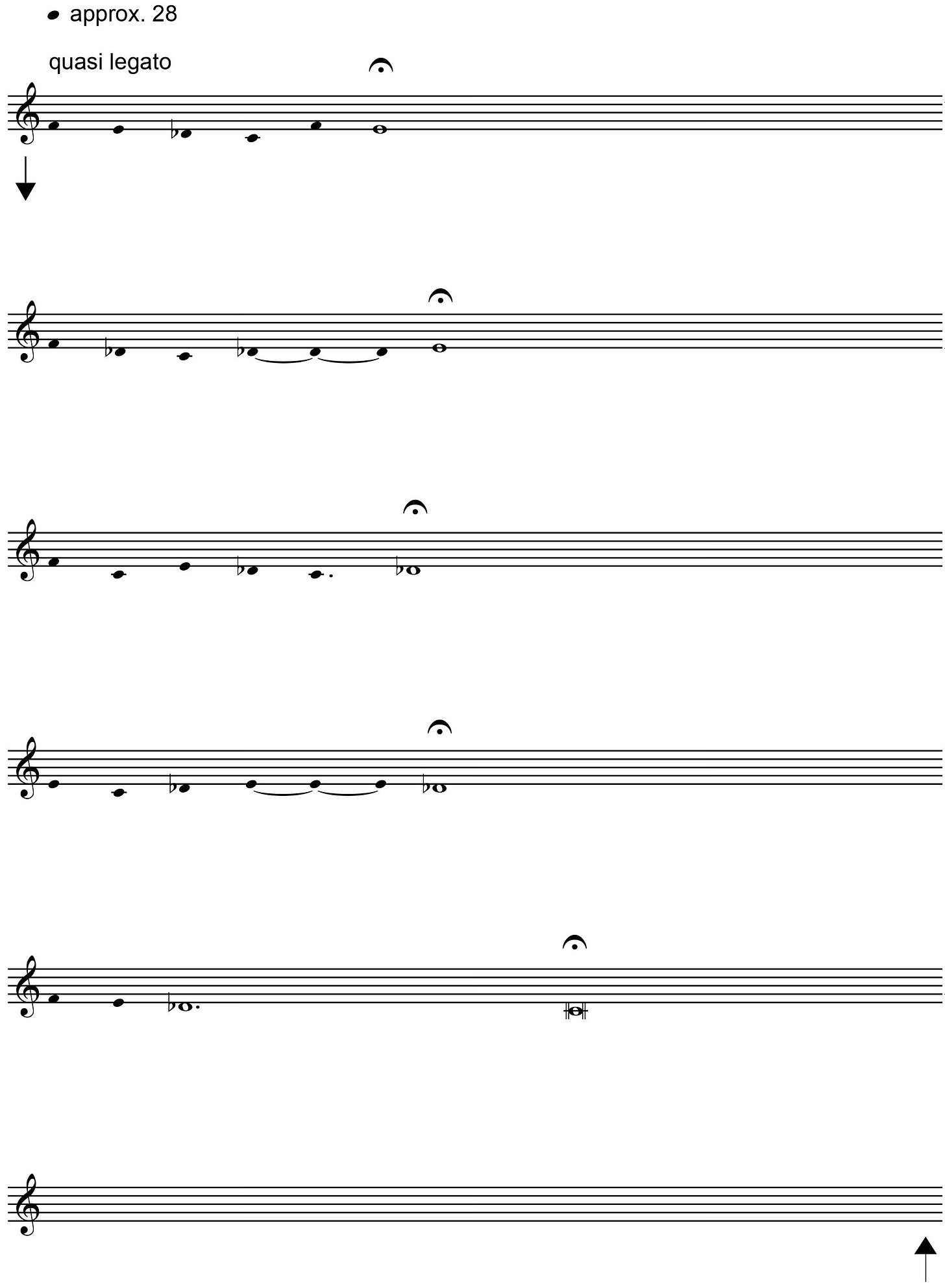

Jaap Blonk recently released the book AsemiQuads, featuring his recent, always distinctive visual poetry. See 1/18 again for a sampling of Blonk’s notation.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $1.25 to $3.36 for January and $6.35 to $8.47 for February. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Anastassis Philippakopoulos is a composer and pianist. Over a video chat edited for concision we talk about Greece and America, monophony and polyphony, composition and improvisation, rumination and intuition.

Recent releases include piano 1 piano 2 piano 3 performed by Teodora Stepančić.

Anastassis Philippakopoulos: Hello, Keith.

Keith Prosk: Hey, Anastassis. How’re you? Thank you for taking a call so late at night.

AP: Yes, yes. I'm very happy to talk with you.

KP: Well I've got some questions planned out but feel free to take it in any direction you like.

AP: Exactly, that’s the improvisatory process, which could be interesting… maybe sometimes I also ask you something.

KP: Oh yeah, of course, always feel free to. I imagine a lot of musicians spend quite a bit of time thinking about what they do and maybe why they do it so sometimes it's a little nice to switch it up and think about it on your feet maybe.

AP: For me it is very interesting how this music talks to you so this will help me also to react. I prefer having dialogue, not monologue. So you can ask me whatever you want.

KP: Perfect. So a lot of your ewr catalog pieces are for piano, the traditional composer’s instrument, and then quite a bit are for flute and clarinet - a lot on the low end, bass flute, bass clarinet… though maybe some of those songs in clarinet in a might recall its prominent place in Greek folk musics - but for a relatively large catalog your instrument selection is relatively narrow, so I guess I wonder what draws you to these instruments. And with those associations of the piano and clarinet in a is there a way that you consciously use them as a kind of springboard off of tradition?

AP: Well, first of all I find it very interesting that you start with this question. I will say that not only my instrumentation is very narrow but something more than that. The majority of my pieces, with the sole exception of three pieces for string orchestra that I composed between 2007 and 2012, are for solo instrument. Piano is the instrument I learned to play as a child. I feel that I'm not the kind of composer who will very intellectually orchestrate, but I prefer to be connected with one instrument, and this instrument is the piano. And there are also many other reasons why I love it. For example, Satie and Feldman are two good reasons, I guess. For my monophonic melodies, clarinet has also a special importance because as you very well said it is connected with Balkan folk music, Greek folk music. At the same time it is a very beautiful western instrument, if we listen to Mozart’s and Brahms’ clarinet quintets or the way that the second Viennese school made use of it. The colorations are subtle, introverted and somehow “shadowy” in clarinet.

KP: So the solo aspect certainly seems to feed into this ruminative feel that your music can have and…

AP: Can you explain to me what ruminative means, I have a vague impression…

KP: Yeah, kind of reflective or meditative maybe…

AP: Yes, thinking inwardly.

KP: Yeah. And then definitely overcrowding would dash or get rid of the character of what a lot of your pieces seem to have but is there a reason why you’re drawn to solo instruments?

AP: So your question goes to monophony maybe? Or we can talk also about the piano pieces which are polyphonic somehow?

KP: Yeah, both. I guess, what draws you to just a single performer rather than multiple performers?

AP: Yes. That’s a very good question. I think you answered that before in a way and we can continue in this direction. I have a necessity for my music to be ruminative, as you said. If I can convey my thoughts through one instrument, that means I don’t need a second instrument. It seems that through the choice of one instrument I wanted to secure a kind of “unity” which was always important for me. Then, having this “unity” I could proceed to other questions of form and expression.

KP: Yeah. Maybe seems a bit circular but it seems like you’re concerned with individual expression and for that to be possible the expression needs to come from an individual type of thing.

AP: For me, as someone who comes from south eastern Europe, the music of the eastern Mediterranean became increasingly important. Ancient greek music - the very few examples we have from it - Byzantine music, Arab music, the music generally of Middle East is monophonic. So I have found myself in this dual position, from the one side to love and to study the western tradition and from the other side to discover a special beauty in the monophonic melody of the eastern Mediterranean and the Near East. I don’t want to make the mistake - because in my opinion it would be a mistake - to take melodic elements from eastern traditions, to orchestrate them and to make a kind of counterpoint on these elements. I want to have my music somehow naked.

KP: Yeah. Since you mentioned the Near Eastern or Greek folk music, whenever we go to a Greek service at a church over here, it’s all monophonic chants, so I can see that playing a huge part…

AP: Most of my recent piano pieces, if we listen for example piano works with Melaine Dalibert, are monophonic…

KP: Yeah. So even though most of your music is monophonic melodies I think when we first started talking I mentioned that I almost didn’t recognize… or, I put on Melaine’s realization and I later recognized the piece while listening to your realization not by the melody but by the harmonic behaviors happening in between the notes, in the overlapping decay. And you mentioned that you weight these behaviors as much as the notes when thinking about a piece. But, yeah, I guess, how do you think of that happening with your piano pieces but not necessarily with your wind pieces. In a way it kind of asks you to listen to the space in between the flute and clarinet notes a little differently than the piano notes when those two kinds of pieces are juxtaposed but how do you think of that space in between notes when you’re using different instruments?

AP: From the one side, at the clarinet and flute pieces we have total silence between the phrases, whereas in the piano pieces we have this - let’s say - cloud of harmonics, this resonance who dies away. These are two different worlds for me. Through this differentiation we can see that for me polyphony somehow exists in monophony because in the piano pieces when we have this small cluster inside the tetrachord then we have a kind of polyphony. So this is maybe why I tend to write in the recent years my melodies for the piano. I love this cloud, this resonance that stays there in the air and gradually fades away. Sometimes I think that maybe the melody itself is simply the preparation for this cloud. You have said to me something similar in the recent past.

KP: Yeah. I have a bad ear for pitch but whenever you sent me the scores I saw the branching pathways the melodies take, where they frequently start from a similar point and move through similar points, so it makes sense that that’s happening. But yeah I recognize it less from the melody and more from the harmonic interaction, or that kind of cloud. So between your realization and Melaine’s realization, those behaviors were similar enough for me to pick up on it, and I imagine those are somewhat determined by the pitches, but your pieces also allow for a variable time or a variable shape…

AP: Ah, Melaine played the pieces slightly faster as I do. And he gave to the resonance slightly less time than I do. I think that his interpretation is more communicative and more extroverted, something which I find very positive. I let more time and maybe sometimes the pieces become slower and slower. It is like a slow movement you know, where one conductor plays it a little bit like andante and the other like adagio.

KP: Ah, OK. But are those kinds of harmonic behaviors a key to a realization of your piece? Because I noticed they aren’t explicitly talked about in your direction other than maybe implied through legato.

AP: The most important thing is the formation of the melody. Very often my recent pieces are written in the space of only one tetrachord. So the most important thing is to find a lively world inside this tetrachord, how the melodic phrases will move inside this space of a perfect fourth, or sometimes a diminished fourth, or sometimes an augmented fourth. I search to find expressive curves for the melody to go inwards and outwards and to overlap. I expect the sustain pedal to be down all the time and this is something that I learned from Morton Feldman whose music I discovered when I was a student. And then I expect a soft dynamic. I wouldn't say, you know, “four pianos” and “five pianos” and “three and a half pianos,” no, I don’t like that. Just “pianissimo” or “piano” is written, and hopefully the performer will understand. I don’t want the score to be too dense in information. Sometimes a “quasi-legato” is written because I want the melody to be connected but also every tone can be clearly itself. Diminuendos, crescendos and also complex rhythmical values are avoided. A “poco-rubato” is written and hopefully the instrumentalist will somehow get into the climate of the piece. I want the score to convey a clarity, a meditative tranquility and a friendliness. It is just a melody, a slow taqsim.

KP: Mmhmm. Nice. So some time ago whenever… I think it was probably for wind and light, in an interview with Yuko Zama, you mentioned that you mull over or work through these melodies on walks. Is that still mostly true?

AP: It is mostly true. Through walking my thoughts become slower and more relaxed and I also observe fine things at the outside world and also inside me. Walking helps me feel and think of my melodic phrases with more clarity. But at this period I try another way of creating music, I mean improvisation. Just to sit at the piano, record an improvisation and see if this talks to me.

KP: Nice. Because we were kind of talking about that harmonic cloud it seems like whenever you’re on a walk working through the pitches it would be easy to imagine the pitch information but difficult to imagine the harmonic interaction whereas with the improvisation, when you’re at the piano, you can feel that in real time, the harmonic interaction.

AP: If the composed melody functions well, if it is well crafted, then the cloud afterwards will be also satisfactory. The cloud contains the essence of the melody. Maybe with improvisation I will gain something else which for me is still unknown. A kind of freedom to accept more of my intuitive self.

KP: Yeah, just always trying new things. And I guess between with at least the walking method of working through music and… for me it's difficult for me to think of traditional Greek music without dance. I guess music is movement, time is a measure of movement, so…

AP: Maybe a slow dance then…

KP: [laughs] yeah. Is there a consciously kinetic component to your music?

AP: Yes there is. Melody is from its origins a means for movement. Monophonic melody moves – the way I feel it – with much freedom.

KP: Mmhmm. Yeah your piano melodies definitely seem to be a little wandering, almost branching where a lot of the chords might start in the same place and then they’ll go a slightly different way in each line. Specifically the one that you sent me, 2019, where a lot of the melodic lines, they start on the same pitch and they’re kind of variations on each other. I don’t know, it kind of feels like you’re lost on a walk because you’re seeing similar vegetation but feel you’re in a different place type of thing.

AP: As you mentioned before that piece, 2019, the three first phrases start from the same tone and they go down. Each time they move with different skips and steps. Did you know that in ancient Greece the natural movement of the modes was downwards? I find this very inspiring… So from the one side the tetrachord I use at this piece is very often found in the music of the Middle East, and from the other side the analytic process of the relations between the tones is certainly influenced from my studies on western music.

KP: Yeah. Do you feel any tension at all between this eastern and western approach?

AP: There is a tension but there is also the beauty of it. If you would ask me what kind of music I'm listening to during the last months, there is a musician, his name is Munir Bashir, he plays the oud. A great musician from Iraq. And at the same day I could listen to chamber music by Joseph Haydn or Robert Schumann or Jürg Frey’s string quartets, or Antoine Beuger’s jankelevitch sextets, or piano music from the earth and the sky by Michael Pisaro. So there is a beautiful tension, which brings all this music together.

KP: Yeah. I feel like tension and ambiguity is where the beautiful stuff lies. So to maybe talk about another tension, you spend a lot of time analyzing the melodies, working on the melodies. I've also noticed that outside of maybe some early pieces there’s no revisions of your pieces. So it seems like there’s a lot of time really grappling with something and then it just rests…

AP: Thank god [laughs]

KP: [laughs] I guess, is there something conscious that allows a piece to rest after so much time working it? And do you have urges to revise that you have to resist?

AP: It is true that each one of the pieces takes many months to be composed. And if a melody wants to remain “unsolved” for years, it is not a surprise. I don’t work with deadlines and don’t take commissions. I let the piece work with me as much as the piece wants. The good news is that there is a moment where I find the melody, and I feel a deep satisfaction when this moment comes. Then I can continue singing or playing the melody but I don’t search any more.

KP: So just an intuitive feeling.

AP: Very intuitive, yes.

KP: And then going back to the Yuko interview, another tension as well, you mentioned when you’re walking around Athens you kind of see the seat of western civilization along with modern buildings that are much more ephemeral. Are there some ways that that filters down into your music?

AP: Although I studied composition in Berlin, I didn’t stay in Berlin. Afterwards I decided to live in Greece because I wanted to communicate with this dimension of time which goes back for many hundreds of years or even thousands of years. I can feel it here. It’s not only Athens, it’s also Crete, where my mother’s family comes from, and also many small islands. Living in Greece possibly did not help me create an academic development. I didn’t become a university composer. But I prefer that I stayed here and worked more personally with my music, always in a creative dialogue with many composers and performers coming from other countries. Certainly I would have more chances to develop an academic career if I was living in western Europe or in the States. But I didn’t follow this way.

KP: I’d do the same thing if presented with the choice. Preserve my sanity and keep my love away from business and career.

AP: Yes, that’s very nice, what you’re saying. For me it would probably be a burden to be a full time academic teacher and to write my music. I prefer to work in a more poetic way. But this is a subjective decision. Other colleagues could certainly manage in a beautiful way to be academic teachers and great composers.

KP: Mmhmm. Interestingly too you make a slow music and if you think of that way of life as well it’s also slower. Just kind of mimics it.

AP: I’m trying to keep my everyday life at a slow pace but it is not easy.

KP: Yeah. Makes you wonder if people who live faster lives make faster music [laughs]

AP: Normally somebody would expect that American people work fast and hard and not have free time. But you seem to have time, that’s very beautiful.

KP: Yeah I try to go against that norm. I definitely enjoy a slower life. I think most people do. Just particularly over here I think it’s very engrained to want to appear busy and moving and working.

AP: Same here in Greece.

KP: Yeah it really seems to be a capitalist culture, you know. You just have to always be producing something, you have to always be growing and it’s rough.

AP: That’s rough.

KP: Yeah. I think it’s just a lot more fulfilling to live a life where you can take the time to breathe and you can have your own personal communion with nature or whatever it is that allows you to rest so you can give yourself to others. There’s no giving to others if you’ve been drained of all you can give.

AP: I agree so much with that.

KP: Yeah. So I guess when you’re… just returning to the allusion that you sing your melodies as you develop them, when you sing it’s in your whole body, you feel it in your chest. When you transfer that to a piano, how much of that is lost or how much of that feeling do you try to preserve as it moves to piano?

AP: That’s a good question. I guess that the qualities I subjectively choose in my singing, I also try to put them in the piano score. The “singing” of the melody at the piano can also be humble and discrete, not with too much expression but also not cold.

KP: Mmhmm and I mean of course the movements you’re making with your humming translate to the pitches on the piano but would you say that the vibrations that you feel in your chest, is that conveyed in the harmonic clouds on the piano at all?

AP: I enjoy both ways. Through singing I have this vibration in the chest as you said, and you have also the silence afterwards. The total silence, the absence of the voice. At the piano you have the cloud of the harmonics. I feel that both ways are good. So maybe through the piano I discover again polyphony as a second step of composition. The polyphony behind the obvious monophony.

KP: Nice. So we've been dancing around maybe some stereotypical characteristics of music that’s associated with wandelweiser like silence and time, flexible time. Historically… I've heard on the grapevine, I think it was Gil, I think he was saying whenever you first joined the collective that some people were a bit shocked that someone who composed these very beautiful melodies had found their way to the collective.

AP: Antoine was from the beginning positive with my melodies. He has explained to me that my music is somehow connected to John Cage’s music. I can understand that some people were shocked. But it was a creative exchange of music, the composers in the wandelweiser circle were always open to listen to each other’s works.

KP: Mmhmm. Yeah so your flexible time reminded me of Cage. It looks differently on something like his number pieces where he has time brackets but that people are allowed to determine the shape of things… similarly it seems you give quite a bit of flexibility on how the shape of your melodies actually come out. I think a lot of times in your direction you mention that the last note with the fermata should be two to three times as long and of course you could play all these notes relatively quickly but that would probably be a bad interpretation…

AP: There is an (approximate) tempo indicator in the piece which helps.

KP: Oh, yes. But I guess you could also see the maximum possible length that you could sustain the note and then divide it by two or three and figure out your melody that way but then you’re so locked in that that seems like a bad interpretation too. So it encourages performers to actually play with time… You know now that we’ve talked about singing a bit the wind instruments don’t have that resonance in between just like the voice loses resonance very quickly. You might have mentioned this in the very beginning of the talk, but for something like the resonant clouds being so important for the piano music how do you think of the silence in between the notes for the wind pieces?

AP: This is an other world. I learned much about the experience of silence at the summer wandelweiser concerts in Dusseldorf. I gradually incorporated more silence in my melodies for flute or clarinet. If you compare for example onissia from 2002 and song 10 from 2016 you could see this change.

KP: And going back to improvisation, does that coincide with any other changes in your musical interests?

AP: The interest for improvisation is related with the need to take some distance from the analytical process of composing my melodies and trust my intuition more. To allow more freedom.

KP: Yeah and do you find… so a lot of times I guess improvisers, they might maneuver with intuition because of a familiarity with their instrument but…

AP: There is a danger there…

KP: What have you found?

AP: I think it's a danger if I improvise with my fingers. That would be very boring. And I would be the first one to be disappointed with that. I would like to improvise without any need to be virtuosic. I wonder what kind of music will come out if I stop thinking. And at the same time, feeling more, listening deeply what comes out simultaneously during improvising. Keith, I wonder, are you connected with other composers of the wandelweiser circle? Music that you know well?

KP: So, my listening, I really sort of started out listening to rock and then jazz and only really within the past few years have I really started digging into this area of music so some of the larger pieces from the past I'm aware of but a lot of my listening is very recent. So with the wandelweiser composers I've heard some stuff from uh… obviously all of your stuff, Jürg, Michael, Eva Maria, Burkhard… and André Möller is another favorite… but I'm not aware of everyone and the farther back I go the more that becomes true.

AP: There are so many great CDs in the ewr catalogue..

KP: So Gil has actually completed an interview with Michael that’s going to publish in a few days. That was an interesting interview, it was a little more… I feel like I have to be more from the heart and Gil and Michael know the names of philosophers and stuff like that [laughs]

AP: It’s good that you’re from the heart, it helped me share thoughts.

KP: Yeah. But other than that a lot of the younger people I'm more familiar with. We published an interview with Kevin Good recently, who studied under Michael for a bit, he’s a vibraphone player. And Sergio Merce and Cristián Alvear were other early interviews in the newsletter.

AP: Yes. It’s interesting that people who are attracted to the wandelweiser often come from rock, jazz, etc.

KP: Mmhmm it’s difficult to say but listening to like Nirvana as a teen and stuff… [laughs]

AP: I was listening to The Doors at my early teens.

KP: Yeah, yeah, but what I was always most drawn to was the extended technique stuff anyways. Like it was the feedback solo that interested me or the character of the distortion. So I think it makes sense that I eventually found my way towards stuff that really mostly dealt with non-traditional techniques or approaches.

AP: Yes, you see for example my music has nothing to do with extended techniques. I go back to the very basics. But maybe my approach.

KP: Yeah. And there’s definitely… it’s come back around. There was probably a period in my life where I was a little angrier, edgier and I wanted something loud and something noisy but it’s come back around to where I really enjoy something that just sounds beautiful too and I think what particularly draws me to you compared to some other wandelweiser catalog composers in particular is that harmonic interaction between the piano notes. I think a lot of the music that I try to write some words for, it’s often all a very very narrow strain of music dealing with harmonic interaction [laughs]

AP: Thank you so much for your interest in my music!

KP: That’s all that I had mapped out but did you have anywhere else that you wanted to go?

AP: If you are OK with it I am also OK with it.

KP: Well, have a good night and thank you so much.

AP: Have a good day with your son!

KP: Yes. Hopefully at this point he’s napping. I will say, sorry to keep you, one thing that I've found that’s super interesting is that my relationship with sound has been completely turned upside down with a newborn. Because your ears always have to be available and aware, you can’t listen to stuff all the time or for long. A lot of the time we have on white noise for soothing. We have played him a lot of music but it generally has to be soft. I typically listen on headphones but my ears have to be available. Not that I always have music going anyways, I treasure silence, but it’s been a drastic change to… it’s constant awareness of listening without listening to anything in particular and then it’s a lot of white noise [laughs]

AP: Beautiful, a very deep experience!

KP. Yes. Well, good night.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

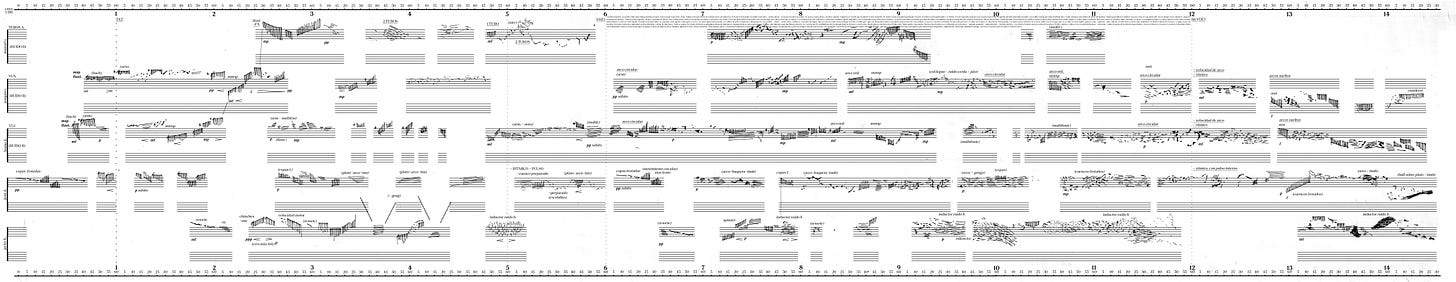

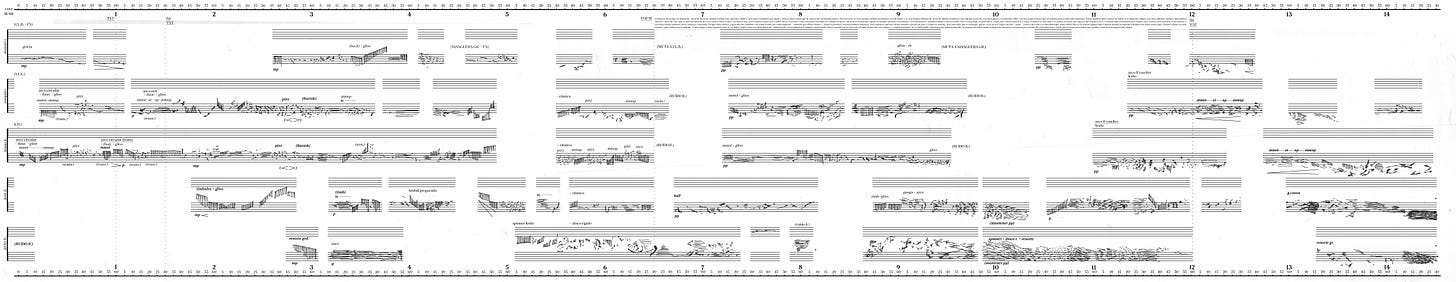

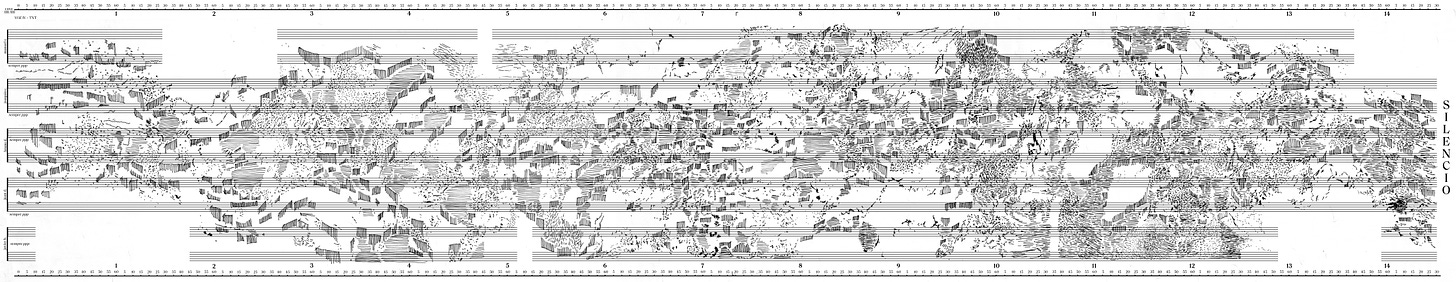

Julián Galay - Casa (2018)

Julián Galay is a composer that works with sound, moving image and language through experimental film, performance, installation and edition. Between sound spaces, places and personal relationships, often utilizing field recording, tuning forks and sine tones for instruments. Some recurring collaborators include Javier Bustos, Craig Pedersen, and Ángeles Rojas. Some recent releases include ɣ and breathe into the forest, into the bird, into the song with Ángeles Rojas and Eine Stadt, Ein Haus. Julián operates the SELLO POSTAL label with Nacho Castillo.

Casa is a 2018 composition commissioned by and site-specific to Centro de Experimentación del Teatro Colón for Javier Bustos, Joaquín Chibán, Bruno D'Ambrosio, Juan Denari, Manuel Rodríguez Riva, and Bárbara Togander who perform with electronics and non-conventional instruments, expanded violin and viola, expanded cello and contrabass, percussion and objects, modified clarinet, alto sax and bass clarinet, and voice. A four-act sound play, the first three pages carry a narrative text and performance objects include glass cases displaying vegetation and miniature buildings in states of destruction. The final act combines the contents of the previous three. The score, charcoal on tracing paper for easy overlay, contains an absolute timeline, traditional dynamics indicators, and embedded textual direction for instrument, technique, and expressivity but its splintered staves contain beamed stems, diagonally flowing lines, and percussive marks more gestural than pitch information.

The sometimes dreamlike text seems to explore when a house is not a home and shelter betrays its purpose through illuminating the destruction inherent to its creation. A great tree is felled for lumber, a soul decays in an infirmary, a house encroaches on tiger territory. These stories amass for a babbling narrative in the end. An explicit theme of the piece is this destruction of language and like globalization kills local dialects a new whole is created but at the cost of its individual components. The distinctly structural interlock of parts in various orientations of the final minutes, made possible through these gestural marks and their overlay, mimics the motif of the text and constructs a kind of wall both on the page and perhaps sonically the density of which seems likely to be more baffling than comforting, a feeling more trapped than kept. Its designation of parts by performer over instrument on a shared page distinguishes the right kind of collectivity from assimilation, its site-specificity places the local over the global, and its particular notation sets it apart from the kind of standardization it might critique.

reviews

Beliah / Heilbron / Majkowski / Shirley - Bertrand Denzler: Low Strings (Confront Recordings, 2023)

Sébastien Beliah, Jon Heilbron, Mike Majkowski, and Derek Shirley perform two Bertrand Denzler compositions for Beliah and three other contrabassists from the titular series on the 40’ Low Strings.

The guttural groan and growl of these strings sustain for the duration and from them comes a catalog, a menagerie of harmonic interaction. Hoot owl beats. Wind buffeting. Singing sirens. Doppler whirr. War drum thrums. Turning motors. Celestial wobbles. A turbulent flood of musical movement from what seems minimal manual motion. But the subtle variation of bowing action still audibly tethers itself to the behaviors of beatings. The relatively stable periodicity of players sounding in tandem or the volatile excitation of broken, offset overlapping relationships. The sense of harmonic expansion with increasing volume under greater pressures. The rolling undulations of slower bowing and frenetic vibrations of quicker action. Sometimes multiple beatings appear simultaneously, rippling through one another as in a pool of reflection and interference. Low waves slow the others down; high ones send a swiftness through them. Composed around the same time as the suite of bass explorations for Félicie Bazelaire, Basse seule, of which the shared continuousness of sounding conveys a kind of systematic searching of harmonic possibilities, with changes made more apparent in their proximity, compared to the more free yet disorienting expressivity - and deeper timbral palette - of the cellular structures and silences of developments like the Arc series for CoÔ.

- Keith Prosk

Bertrand Denzler / Jason Kahn - Translations (Potlatch, 2022)

Bertrand Denzler and Jason Kahn play a 35’ set with tenor saxophone and electronics on Translations, their first meeting

Some moments approach textural and gestural mimickry, that one could become the other. Electronics accommodate saxophone by not sustaining inhumanly and maybe saxophone meets electronics in not moving too swiftly. Static crash abuts breathy friction. Clicks juxtapose popping tongue techniques. Beeping feedback squeals with shrill trills. Arced coos alongside gliss. But timbres never blur. Maybe they even diverge, more normative sax tones and the distinct noise in the ballpark of radio-like static and feedback of this setup in increasing frequency toward the end. Saxophone doesn’t follow electronics as closely in frequency as it probably could and electronics don’t engage in overt rhythms with saxophone though they probably could. Mimicking but seemingly purposefully refraining from the areas of the instruments at the points closest to the other to underline the boundaries and the choice of the player, the heart of improvisatory contexts. Or maybe it was a wish for a few moments but perfect alignment is not possible so soon. Either way, it sounds the social negotiations, the tensions and the happy affinities, of a first meeting with rare clarity.

- Keith Prosk

Preview and purchase Translations at Potlatch.

Tristan Kasten-Krause and Jessica Pavone - Images of One (Relative Pitch Records, 2023)

Tristan Kasten-Krause and Jessica Pavone play four suites of harmonies on the 38’ Images of One.

One of two they move between resonant unity and more polar play. Drifting apart and rejoining in phasing relationships in gliss as easy as the concavely meniscused waltz of falling leaves or the more angular staccato zip of herringbone. Across motivic gaps, to join and drift again in other material. Even their frequency ranges appear to often overlap, though the different bodies and their strings’ sympathetic resonances amongst their neighbors always conveys the distinctive timbres of each. To beat sweetly or for sour harmonies like alarm sirens. Zooming in and out of sounds in slowing and hastening time. In alternating tension and calm. High and low two sounding the tide between them that connects them, relates them.

- Keith Prosk

Quatuor Bozzini - Éliane Radigue: Occam Delta XV (Collection QB, 2023)

Isabelle Bozzini, Stéphanie Bozzini, Alissa Cheung, and Clemens Merkel perform two 37’ realizations of their delta from Éliane Radigue’s Occam Ocean across consecutive dates on Occam Delta XV.

If it were only the numbered series of releases from shiiin, that each Occam recording introduces something special could be considered a conscious aspect of presentation but as this characteristic continues through independent presentations too it might illuminate the naturalistic diversity inherent to a system whose foundation begins with the foundation of life. Recordings have seemed to so far systematically introduced occam, river, delta, and ocean forms, traced one performer through them, provoked comparison of behaviors in instrumentation with all strings or all winds. Always each showcases the relationship of the performer to their instrument and the limit of each. This delta feels special in that while other ensembles - Zinc & Copper, Decibel, Onceim - are anchored by a chevalier with an occam Quatuor Bozzini stands without as a kind of unit unto itself. This is also the first presentation to provide two recordings together, across consecutive nights and, though it’s ambiguous, I assume the same place.

And it is the first delta to sound deltaic to me. The quartet begins closer to unison than it ends, with the gradual recognition that bowing cadences seem to have drifted towards their instruments’ natural frequencies, twin violins in relative ecstatic excitation over low and slow cello, having got there by a meandering way that felt in the moment to be suspended, slow bowings’ strokes carving bank and bar in epochal time, a rise in volume splaying harmonics like the channel widens at the space it splits, the intuition and the information of never stepping in the same river twice. In between always a world of harmonics like life under a microscope, teeming. A few provide markers across evenings as fossils would. A kind of high-tension tanpura buzz. A dancing satyr fluting. The differences are subtle but tangible, felt more than known and ineffable. Perhaps the satyr’s bolder on the first night and the tanpura on the second. But it lights the imagination to wonder the minute physical parameters that would change the sound, the pressure and the temperature of the room one night or another, beyond the infinite variations in the performers’ hands.

- Keith Prosk

Biliana Voutchkova & Sarah Davachi - Slow poem for Stiebler (Another Timbre, 2023)

Sarah Davachi and Biliana Voutchkova arrange and perform the Ernstalbrecht Stiebler composition dedicated to Voutchkova, Für Biliana, with reed organ, violin, and voice on the 49’ Slow poem for Stiebler.

The further away from the current moment the more the sands beneath my words shift but back when I tried to write some words for Für Biliana it’s interesting to read that I could have confused the solo for a duo and some sounds for organ. So though the duration expands eight times and the progression of tones modularize into sometimes unrecognizable combinations the extension feels natural, accentuating the sustain, sonority, and movement of the original. Slow speed, sustain, and states of repetition shape a sense of suspension. Oscillating rhythms and circular structures sound the space shared between these two states. The sound mimics the form as closely as water would. In floating, bobbing upon a swaying sea of tender ether desublimated from hymnic beatings in quavering tremolo that hastens and slows and sings. Living and listening for the moment and so laboring to extend it. Letting sound shape shape time as much as the arrangement. With more mutualism manifested in the harmonic interaction between these two performers and even reflected at the title level between composer and dedicatee.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for sharing time with harmonic series.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $1.25 to $3.36 for January and $6.35 to $8.47 for February. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.