1/27

conversation with Zheng Hao; notation from Ben Zucker; reviews

Point of Departure 82 is available, featuring: Brent Hayes Edwards in conversation with Bill Shoemaker; Patricia Brennan in conversation with Troy Collins; Stuart Broomer on Seppe Gebruers' Playing with Standards; Daniel Barbiero on Gerry Hemingway's Kwambe; Kevin Whitehead on Sonny Rollins and Sam Rivers; excerpts from the books Holy Ghost and Saxophone Colossus; and Chris Robinson on recordings of Zoh Amba.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $6.35 to $8.47 for February and $4.42 to $5.89 for March. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Zheng Hao and I speak over video chat about deformation, professionalism, illusion, mischief, sensitivity, and control.

Recent releases include A Clipping Isle with Crimson Chaos, Another Time with Sun Yizhou, once upon a time there was a mountain and three mixes with Ren Shang as Oishi, the solos Harmonium and Last Day of the Cold, and contributions to the compilations Electronic Induction 2022 and Skronk #121.

Keith Prosk: Hey! How’re you doing today?

Zheng Hao: Good. The weather’s been very kind of cloudy so I just stayed in, working for this, trying to prepare better for this conversation.

KP: Oh, nice. No need to prepare, it’s usually just an informal chat but yeah I actually looked up London weather, we have very similar weather today. We’re also kind of cloudy and about the same temperature as well. Y’all are closer to the ocean so you’ve got a little bit more humidity than we do and we’ve got a little bit more wind but yeah how’s it going?

ZH: Yeah good. Should we follow the questions that you sent over to me?

KP: Yeah for sure we can follow that general map. So you are in London right now?

ZH: Yeah.

KP: Nice. Are you originally from Beijing?

ZH: No, I'm from Wuhan.

KP: Oh nice. How’d you get into this area of music?

ZH: I was trying to pass the exam of CAFA in Beijing when I was a high school student - that’s when I first knew Sun Yizhou - and then I didn’t really do well in exam and I didn't want to do a gap year so I started to apply to go abroad for studies. Around that period I was still doing fine arts but after further research in fine arts I kind of realized that I'm not really interested in this. I also play some instruments so I thought that I could try to apply to some music related course. And then I saw this course name called electronic music and computing technology at Goldsmiths, which is the course I'm doing now. And so when I was preparing for this I kind of get to know computer and electronic music more properly and then I get reconnected to Sun Yizhou and that’s how we made the album Another Time.

KP: Nice. Since you mentioned that you came up through visual art, just to give people a sense, what was your visual art like? Is it related to what you’re doing in sound?

ZH: It has some changes in the process but originally I was doing text and poem related stuff which, through all these changes that I was doing, I am still doing the text thing. I was doing some drawing in the middle which associates with geometry, optical illusion things. And then after that I kind of fall back to text. Well, this is kind of related to those graphics and text on my website. I have this strong aesthetic or obsession in the idea of topology, which doesn’t necessarily have to be so mathematic or maybe poetic related but essentially the idea is that the graphics are still recognizable after a certain amount of distortion through time. So that’s why I do those on my website, trying to approach this topology idea. Say the quads for example it actually comes after the experience that I played with other musicians that I realize there is this kind of… I guess we could say this is kind of social relation related but it’s also, say, in the quartets that people are playing together, if you think about each musician as a point and then start to consider the distance between those different musicians and who has more words to say, if I want to keep a balance should I be more quiet which means listen more. These might not be scores I would say but it’s kind of related to expressions and extractions from experience. Yeah. I actually do have a lot of things that I wanted to say for the last bit, what might a bad interpretation look like for the writings and the ideas around notation, but I think it might be better if I write it to you cause I don’t know if I could express this as expressive as I want it to be. I was writing down lots of ideas from the beginning, which I feel more confident to talk about those, so I might write to you about the last bit.

KP: Yeah, that’s perfect. But just before I forget, since you mentioned with your visual art you were interested in a topological deformation over time, does that relate to what you’re doing with Ren Shang, in Oishi in any way, where you have this source material and sometimes it’s raw where it’s very recognizable sometimes it’s overdone to where it’s not recognizable.

ZH: Yeah. I was surprised and also very happy that you immediately understand what we are doing, that some source material is recognizable and the overmix means that it’s unrecognizable. Yes. It’s getting more and more complicated over time because at the beginning we were just kind of having fun sampling other people’s music but we’ve developed the idea of, is it just slightly a bit of a mix, that we are just being the effects like guitar pedals, that we just process it a little bit? Or that we get to be more conceptual, that we would mix a classical music and a rock n roll album together? And then I guess even more and more conceptual that we actually… there was one time we sampled John Cage but it’s just for fun, we didn’t really play the sample and we didn’t really do nothing, we actually sampled ourselves but we kind of inherited the idea from John Cage. But yeah it becomes more and more complicated after we realize that we can sample ourselves because it becomes a stage where we were thinking about how much do we want the audience to recognize, or how do we want to develop the ability to represent the same thing. Because there were a number of the audience that they are actually, they’re pretty satisfied about the album that we did when we were sampling ourselves. That’s when we got to play for the first few times in London. And then we start at a point of how do we represent the idea of… how do we represent the same thing, how do we represent that people would know that we are doing the same kind of in between unrecognizable and recognizable music and how do we both be the sample at same time but also chop ourself up in performance. So yeah we’re kind of stuck at this stage for a bit and now it’s getting fine because, to the question you asked, we get to the original point where we should not consider about what shape that the audience will actually recognize, because the shape will always exist there, that the audience could extract themselves, rather than us trying to pass this information to them again and again. Cause that just would make the journey of making music together a bit more painful because we have too many presets for ourselves. But now it’s fine because it becomes more and more simple, about just preparing this surprise for each other, to bring new sound in. So yeah I guess it’s maybe not that much related to topology graphics.

KP: Yeah so in the recordings with Shang the mixes are kind of set, like you have a raw recording or you have an overdone recording, but in your performances have y’all considered showing the progress of deformation, or is that the part that’s too weighty that you’re talking about where you just feel like you’re locked in? Like a guitarist doesn’t have to be like… like Derek Bailey doesn’t have to play chord progressions and then go, OK and now I’m gonna play like Derek Bailey, he just went straight there you know.

ZH: Yeah, exactly, that’s the idea. That’s why we prefer to talk less but more directly just play. So now we’ve got to a stage where if there’s a live performance we might not practice, we just know what each other might play, might bring, the soundtrack. Now it has become all about the energy. We just confirm that the energy is right and then we will be confident about the performance.

KP: Yeah. And then some of those overdone mixes too, the way there is super different but the sound result could be similar to what you might do with a laptop or a no input mixing board. How do you view what separates those two ways of making music?

ZH: I think it has different orientation. Because when we just started doing the sample music I was still using mixing board for samples, although now I have stopped it. But there is definitely this technique shifting where when I was playing no input it’s more like a closed logic, that it’s looping in between this mixing board, but then when I start sampling, when I have a channel that’s open for sound materials, then the technique had changed. Essentially it just made me realize that I want to have more and more control. Because playing with no input, you always only have fifty percent of control I would say, I feel like I get properly trained to be a reactive musician. I kind of want to have more control and that's why I started using samples. I would say maybe the result, the musical output is the same but it’s definitely… I mean, talking about musical output is essentially talking about music genre, which you can use different instruments to produce sound that sounds the same but the aesthetics and the gestures could be very different and it kind of actually means personality changes as a musician too, I guess. Because it’s too easy to be either a very reactive musician on no input mixing board or be a proper noise musician cause no input mixing board just has the proper characteristic for you to be a noise musician. Also I feel like after I learned more about electronics and computing, this more technical knowledge, I feel like if I could do better, if I could do something that’s more complicated, maybe I won’t be satisfied just playing a certain sound. I feel like there’s a limitation on no input mixing board, where once after you've played with it for awhile you kind of realize it can only produce this many sounds and then that’s why people started using guitar effects pedals. Then the gesture changes from you use the nobs on the no input mixing board to you use the nob on the guitar effect pedals and then musicians become very droney musicians and then they play slowly. Yes it sounds good but I feel like if it’s an improvisation, if you're a performer, the complexity, the challenge for yourself has become less. So I would like something that’s more tricky and you could be more professional, I guess. Also more and more people are using no input mixing board… and I think it’s a good thing. Of course you can take that as a sound source and you subtract it or add it with different filters but then why not build everything from zero. Cause that’s the thing I am doing now, I am now playing with modular synthesis. It became another way to build things from scratch. I might still play it but it’s just not… I guess it’s less attractive to me than it was before.

KP: Yeah, yeah. You use quite a few instruments, at least from the few recordings I've seen. You mentioned pedals, no input mixing board, I've seen bass, cd player, voice. Is that coming from this place of you don’t want to be locked in by one instrument’s tools or set of sounds that it can make, you want a broader palette? Also, following the map a little bit, is there a particular reason why you might choose one set of tools over another for a particular scenario, since you do seem able to choose from so many?

ZH: Well first I would say it’s great to have a slightly larger repository in terms of instrument. Because I was playing strings when I was younger. For me it’s more like musicians have different experiences on different instruments which is somehow similar to learning a language, it always associates with memory and feelings. So if I were to have the idea of, I must use this instrument for this session, it's more intuitive feeling because it’s the imagination of this concept. In Another Time I used bass and voice and cd players but I didn't really use no input and I didn't make very noisy sounds because the idea is to have this home feeling. Immediately for me I would not choose no input, I would imagine, OK I want this to be warmer so I would only go for these two directions and the limitation comes from the imagination for concept. And then in the limitation it could be maybe as colorful as possible. For harmonica, I got the C major tremolo harmonica when I was in high school and I tried to learn it on my own but didn’t end up continuing. But when I was packing up the luggage for London, I still put it into the case. Almost six months later, I was trying things out with a contact microphone and I found the sustaining highest pitch on harmonica sounded really like electronic feedback - so I immediately started playing like that, then I recorded the Last Day of the Cold. In that album, the idea of harmonica being a sustaining instrument had become a feature for me, because when the silence happens, it was nice when it’s blank. So, yeah.

KP: Nice. Yeah and I guess… so a lot of the instrumentation that you do use, it seems to be a medium for feedback. I know you just kind of mentioned the reactivity that feedback requires is maybe something that you're becoming slightly less interested in but what do those different mediums, like no input mixing board or pedals or your harmonica setup or just microphones, what kind of effects do those have on the character or behaviors of feedback?

ZH: Yeah. So no input mixing board, it's a method which you can generate sound through a feedback loop with its built-in amplifier, I would say. And then why no input mixing board is pretty special is because, just physically speaking, in the components, it’s pretty sensitive. Even just subtle changes on the nobs the sound can result in very significant changes, in rhythm and pitch. That’s why it has this really conversational tension if you were to play with it. So that's why as I said generally there can be two ways to play with it. One is you could just press the button or twist the nob in this very aggressive gesture without really listening and trying to make a further decision and it matches the noisy characteristic anyway but if you were to play slower, which this would be the way if I were to play it again, play it slower and listen to the sound carefully, it feels like you get to decide. You have the realization that you get to decide almost every step of the gesture but still there’s always the possibility that it will generate completely different sound than what you expected. And this is great. This is amazing. It can even jump into silence. That's no input, and that's great. And pedals, I guess pedals it's always this in between thing which you use as a tool to subtract or add to the sound from a sound source. It could be guitar, it could be no input, it's like an expansion with which you have more control and prediction. If you are only playing with the guitar pedals, that it’s mixing this only one sound that generates from a mixing board, I guess people would have different preference regarding to this kind of balance. Cause some people will play no input without any pedals, or some people will play no input with a lot of pedals and only try to adjust the nobs on the pedals, and maybe some people have fifty fifty. I guess this is another more interesting path, pedals. And microphones, microphones are great. It's so different to play with microphones if you use it for sound source or instrument. I have this recorder, which is Zoom H6, it generates really interesting feedback sounds. It’s almost like FM synthesis. But other uses such as using air microphone as amplifier for feedback… it’s sometimes tricky because it’s a problem of adjusting the gain volume. One time I did this show where I had another air mic pointed to my desk and I think there’s some misunderstanding in the soundcheck where the sound engineer accidentally turned my gain too loud. I was playing contact mic with harmonicas and when I sat down once I put my hand on the harmonica it started causing this piercing loud feedback and then I was thinking, ah I didn't expect this but OK I guess this will have to be a noise show [laughs] Yeah, so that’s fun too but that’s the problem of air microphone, I guess. It will make the whole room reverb, very reverby, especially playing at small venues, it's just endless. But it could be a very good thing. So, yeah, I guess working with feedback is really relying on gestures and reactions.

KP: Yeah. And so the difference between them is maybe more a question of sensitivity than tone?

ZH: Yes. It’s more about the sensitivity and the frequency of air, like resonations. Which is why it’s actually important to choose microphones for feedback because I would say the two harmonicas, the Harmonium that I did, I think it wouldn't really work with air microphones because it won’t resonate with the harmonicas. The reeds of harmonicas resonate through the contact mics with speakers. Comparing to air mics, the contact mics need to be pressed tightly against the harmonicas/objects to resonate. So the sensitivity, it's very important. And sensitivities could lead to directions and distance.

KP: Nice. Yeah, so let’s talk about the harmonica setup. I kind of fell in love with Harmonium and then I know at least “long breath” off of Last Day of the Cold… yeah. So I know at least on Harmonium you mentioned that your setup includes two harmonicas in different tunings and, just to get some technical stuff out of the way because I'm curious, do those different tuned harmonics, like slightly offset tuning, does that allow for more beatings or for more instability to easily modulate feedback?

ZH: Yeah. I was going to talk about this. I think in my setup, it doesn't really matter about the offset tuning. The offset tuning works like presets, that it generates the more interesting intervals and maybe compositional ideas as well as the musical output. But the beating patterns, yes, it’s a very important process in this track. Because the second track of Harmonium, I think as I remembered it's the only track that has two different channels, the left channel and right channel are different. It’s because I recorded the left channel b flat major harmonica first and then I listened to the left channel when I recorded the right channel with c major harmonica. So there were some binaural beats generated in the first two minutes. That’s the beating patterns. And in my experience and, well… I was very interested in these binaural beats generated so I actually wrote a simple application in javascript to run it because it just works so good in a music therapy way. And also scientifically binaural beats will generate when there’s a difference between two frequencies in the left and right channel when it’s less than 20hz. Usually people would say 3hz is the difference, and then 5hz, 8hz, and 13hz… but anyway the smaller the difference the more intense the beats can be. But how the beating patterns come from is determined by the live equalizing I was doing on the mixing board. That’s what I did when I listened to the other channel when recording. Cause by eq’ing it I get to… yeah, cause I hear the beating patterns directly when I was recording and then I thought, this is great I will keep it. And then the destabilization for modulation is also coming from this equalization. It’s because if you try to adjust the beating patterns you get too lost in it, you twist either of the button nobs too far that you could slide to the distorted noise so immediately. That’s something that I wouldn’t want it to happen but it happens all the time so I can only record twenty minutes per day when I was recording it cause otherwise I would get too anxious. The extremely high frequency is just not good for mental health anyway I guess.

KP: Yeah. So I'm curious too whenever you do get a beating going are you able to stay in that place or is it just a transitional thing for a few seconds before the feedback stabilizes to a new frequency?

ZH: Um, well, there’s two ways of changing the feedback. One is if I change the equalization but the other thing is if I just let this feedback go and I keep… I don’t move at all, I don’t put my hand on the desk, it could stay longer. But of course psychologically speaking your ear might generate another illusion through that difference. But the setup is because the two harmonicas are placed horizontally on the desk and the contact mics, I stick them on the metal part which, when they’re horizontal, it turns the entire desk to a feedback desk too. So when I put my hand on the desk I can feel the resonation through my finger. If I put two of my hands on the desk it changes the pitch sometimes or sometimes it will just stop the feedback. So that’s part of the reason why this album is less sustain. It’s more a lot of changes than sustain.

KP: Nice. Yeah. And just being completely ignorant about harmonicas, when harmonicas are tuned is it just the reeds that are tuned or the whole body?

ZH: I think it’s just the reeds that are tuned.

KP: So whenever you’re using a contact mic is that actually registering the tuning or is it registering that you have a resonant material there?

ZH: Yeah it registers the tuning. Well, it registers the structure. But when I don’t blow the harmonica, when there’s no air cycle through the harmonica, then the harmonica won’t really make a sound because it has this different air path. When it changes the air through the air path it changes the frequency of the air and that’s why harmonica makes sound. But how I make the harmonica make sound this time, the contact mic, it’s feeding back with the speaker which resonates with the reeds. I actually played, in the fifth track, I actually had wind blow through the harmonicas so there was actually a change where it was feedback and then it recorded the sound from the harmonica and then they come together. The textures are pretty different. It’s slightly a bit more fuzzy if I have air through the harmonica. And it’s much more like a sine wave if it’s just feedback from the contact mics.

KP: Mmhmm, yeah. I guess, is there anywhere else that you wanted to go as far as allowing people to imagine what this harmonica setup looks like?

ZH: Yeah. This is where it will go kind of funny, that it almost gets kind of fantasy because there’s actually a story behind why this was called Harmonium. So when I received commission from Jack [Chuter], who’s the label runner of Hard Return, it was in July, I just bought a new harmonica, I started recording in the first week of August, and I decided to experiment with two contact mics on them. But I was also reading this scifi fiction recommended by a friend and it's called The Sirens of Titan by Kurt Vonnegut and in chapter eight he wrote about the only known form of life on the planet Mercury and it’s called harmonium. And harmoniums live in a cave and they take food by the vibrations and they only have one sense which is touch. And Mercury is in tension because of the great temperature difference in the northern and southern planet which makes Mercury sing all the time and each note can last a thousand years and this sound then communicates to the harmoniums through the sense of touch. So that’s harmonium. It’s like this existence where they take the energy from the resonation for food and it’s very simple and pure and it’s also just such a coincidence that it makes it almost like a fantasy. It has this natural fantasy. And then everything became natural, OK this is gonna be named Harmonium and I am gonna use resonations. That is confirmed yes, I just continue this plan, I must continue to use contact mic to record these resonations between two harmonicas. And also Harmonium because it’s the name of harmonica, so… yeah.

KP: That’s awesome.

ZH: Although I didn’t really include this in the bio because… that’s the other thing that I do realize and I do kind of have it for my preference, is to try to not have a concept in a bio when I release music. To make it more like pure listening, that you’re here for the music. Maybe less for composition or the conceptual ideas behind it. But still the story was great so I thought that I had to tell someone at least.

KP: Yeah yeah yeah that’s awesome. Do you see yourself continuing to explore your harmonica setup for a bit?

ZH: Yes. I think I would do a volume two actually but I haven't thought about the setup yet because I think I will need further research in either psychoacoustics or maybe a more involved proper sine wave into this harmonica setup so the sound can be more complicated. So I need to think about it.

KP: You also mentioned a little bit… the therapeutic effects of beating patters, which might imply… something being therapeutic might imply it’s desirable. So compared to some of your we’ll just say noisier stuff do you see yourself gravitating a little more towards this beating music?

ZH: I think I would say yes. It is more the Harmonium release, it is something that is kind of the stage that the music had become more serious in a way, than those releases that I did as Oishi. I think they are, this Harmonium thing, it’s more serious and more confident in a way because it has scientific practice to support the idea of, yes there are these binaural beats… because people have done a lot of scientific research on it. But apart from that I think doing sample music, doing Oishi music, it’s still… I actually find that weirdly more like music than Harmonium because you would question yourself or try to be more professional in musical way. Because you would consider the sound texture more, you would consider if I want to produce more unpredictable sound, or if I want to do sound collage then I should listen to more music, I should have better skills in playing synthesizers and also practice more. But the kind of practice as Harmonium, it feels like it's something that… it’s kind of like a steady practice that doesn’t really affect its pathway, which direction it's gonna go by what I am listening to. Because I would say Oishi’s style that, yes, the style won’t be changing all the time but Oishi’s I would say is changing all the time by the music that we’re listening to at different periods. In that regard I would say, yes, this Harmonium may be more music therapy practice. They don’t change the path, or also probably because I already determined that its genre will stay there, that it won’t involve with any other fusion elements. Say OK yeah I won’t play bass, I might won’t use noise stuff in Harmonium one and two because it’s more like a study. It’s made to show people the study you have done. I won’t say it’s academic but it's definitely more formal for sure.

KP: Yeah. So it sounds like there’s a little bit of tension between… well, you mentioned that Oishi started out as kind of like a fun project, around the Yizhou duo when you have a lot more instruments you mentioned intuition, and then with the harmonica setup you’re mentioning study and professionalism. Is there a tension between this fun side and this serious side that you feel?

ZH: Yes. I would say just in general even the fun side I wish it shows somehow that we are not just messing around, that we are actually professional musicians. That’s why I said yeah we would question ourselves as musicians, like, yeah, you should practice harder or you should not…. even if this is for fun but you shouldn't really just stop practicing, you shouldn’t just bring random instruments into the session or random ideas into the session. But what makes it fun is also considering the audience, that I want to have that kind of comedic element. They are both for audience in some way but as Oishi, the comedic feeling, it’s mischievous. You think about mischievous, you then imagine immediately, yeah I'm playing this kind of music consistently and then all of the sudden I change the texture and then I collage or I have weird voice or I have different kinds of elements pasting together. That’s why this is comedic. And it can even be offensive. That’s why it could be noisier. But it doesn’t mean that we should do things without considerations because I’ve heard about a few musicians, they do live shows say, for example, they use a sampler and then they just play random noise. No rhythm. Nothing that’s analyzable for this entire forty minutes. They just play randomly with no aesthetic that you can tell in their live performance. I've never seen that live before so I couldn't say if that’s a good thing or a bad thing but then I would think about if I wanted to do that kind of music. I would say maybe not. Because it's still more about control. And also about if you are doing this kind of thing yourself it's a very huge difference between you are doing this kind of music with other people. Because if you are determining yourself with a strong aesthetic, you’re only performing this without considering anyone, then there’s no conversation between you and other musicians. And I found that very important in a music practice, where you should think, well I should…. I think I would focus more on a conversational level than have this certain analyzable structure. Because even people, audience now they might seek this certain level of balance between conversation. Where people might say, yeah I just seen your performance and you are much more expressive than the other person, or you listen less. And I would think about, is this a bad thing, are there still structures for you to follow improvisations. Possibly not. So then what do you need to consider. That becomes a problem where it's comedic but it's professional and it might be even more difficult to practice than do more say scientific logic compositional based work.

KP: Yeah yeah yeah. Are you into theater at all [laughs] like comedy and drama, that separation?

ZH: Well I like that kind of collage, the texture changing all of the sudden. It could be as simple as you were walking on the street and the window just changes or the wall just changes. I find that very funny, but in a very simple way. That kind of comedy doesn’t really offend anyone but it's just funny in its own simple and silly way. And I'm hoping the things that I'm doing are somehow similar to that. Which the patterns on the wall could still be very good looking or needs this certain amount of technique to draw those patterns but just the violent cut or something like that could make it very funny. Then it also means people could enjoy it easily. And it's also… I guess I like to see or hear people laugh when I’m playing as Oishi.

KP: Oh nice. So there’s, just going back a bit to the map, I noticed that what you've released so far is mostly solos and duos, and I think I’m just now realizing that these maybe intuitive comedic projects are your duos and these more professional projects are your solos…. I guess, is there something that draws you to smaller groups over larger groups and do you further separate what you want to do with another person versus what you want to do solo?

ZH: Mmmm, yes. I would say in solo I probably won’t do very comedic work. Because that’s… it could be such a simple reason because, say you’re being mischievous, it wouldn't really be fun or you would feel nervous if you’re being mischievous alone but if there is always someone that’s being mischievous with you there would be less pressure and you would do better too. But, speaking of larger groups, I played recently in this ensemble. It started to make experimental jazz. Me and Shang went together actually and she was doing vocals and I was doing electronics and all the other people are instrumentalists and they are kind of really strictly trained I would say. They have to do all this sight reading when we were doing the ensemble. During the practice I do realize that there is always a leader in a larger group, where people listen to this person and they will push things… well it's a good thing because you will get to properly rehearse, you will know how to play this song with a larger group but then it means… I don't know, maybe for me, I'm too mischievous. It's a new experience, that everyone listen to one person in this ensemble. But it’s an experience because I wont say I enjoy listening to a leader or I want to be a leader in a larger group. And another experience of playing larger groups is I actually play in a band but there is still a kind of person leading it. Sometimes we also improvise. It makes me start thinking about compositions and structures cause we’ll listen to jazz music or say bop music where they have these structures where they play things and then they start solo and then they improvise a little bit or maybe further to improvisations. It makes me weirdly think about composition because I’ve never actually really worked with compositions in a bigger than two people group. But when playing in a band I feel like it's somehow similar to roleplaying which I didn’t really have fun but I guess it's just that I feel too nervous when improvising with more than two people. And it's also the lines between different points can get more complicated because it feels like there’s always people who should be listening and people should be taking care of another musician that made a mistake or there’s other musicians follow. Or maybe all these are just illusions that improvisations should just go naturally. But, yeah, I guess I'm just not used to the tension that’s more than two people yet. For me it’s hard to manage.

KP: Yeah. As a listener I super prefer solos and duos because I can actually focus. Once it gets more than five kind of independent voices, yeah, I just start to lose focus.

ZH: Yeah. Also I forgot to say this but, yeah, doing duo and solo are great because it’s focused and you, it’s somehow similar to playing slower, that you are very conscious. I think only playing with one person makes you more conscious in a way. Makes you calmer. It’s easier to manage so you can make more decisions. It’s less sociable in a way too, in the conversations, that you don’t have to take care of too many peoples’ sound.

KP: Yeah. Are you an introvert?

ZH: Introvert?

KP: Do you tend to be a quiet person generally?

ZH: Um I don’t think I am. I think the problem is I am too expressive in improvisations. Sometimes maybe I just couldn’t stop and that’s why me and Shang sometimes work so well because when I don’t stop she don’t stop, she doesn’t care either. But when playing with maybe other people they would stop, they would think about, oh if you are playing maybe I should listen to you and play something that sounds good.

KP: Mmhmm nice. So coming back around to those graphics on your site with the kind of aphoristic writings associated with them, are those scores? And if so, when do you decide to make a score? What might a ‘bad’ interpretation look like, since the don’t have much information around time or sound?

ZH: These are part of my practices in approach to topology - where the minimal graphics are still recognisable after a certain amount of distortion and deformation through time, the graphics and writings are interpretations of each other. A few of them come from the experience after playing with other musicians, for example the quads, and some of them are observations of visuals such as the window one. All of them either contain the potential process of shape deforming or the minimal shape to begin with. I think those texts and graphics are parallel to graphic scoring as they are more like structuring the tension between musicians in the whole improvisation after it ends. It perceives more relations, distances rather than symbols and directions, more like something that distracts you and brings you to a abstract degree when you are looking at the scoring during the performance.

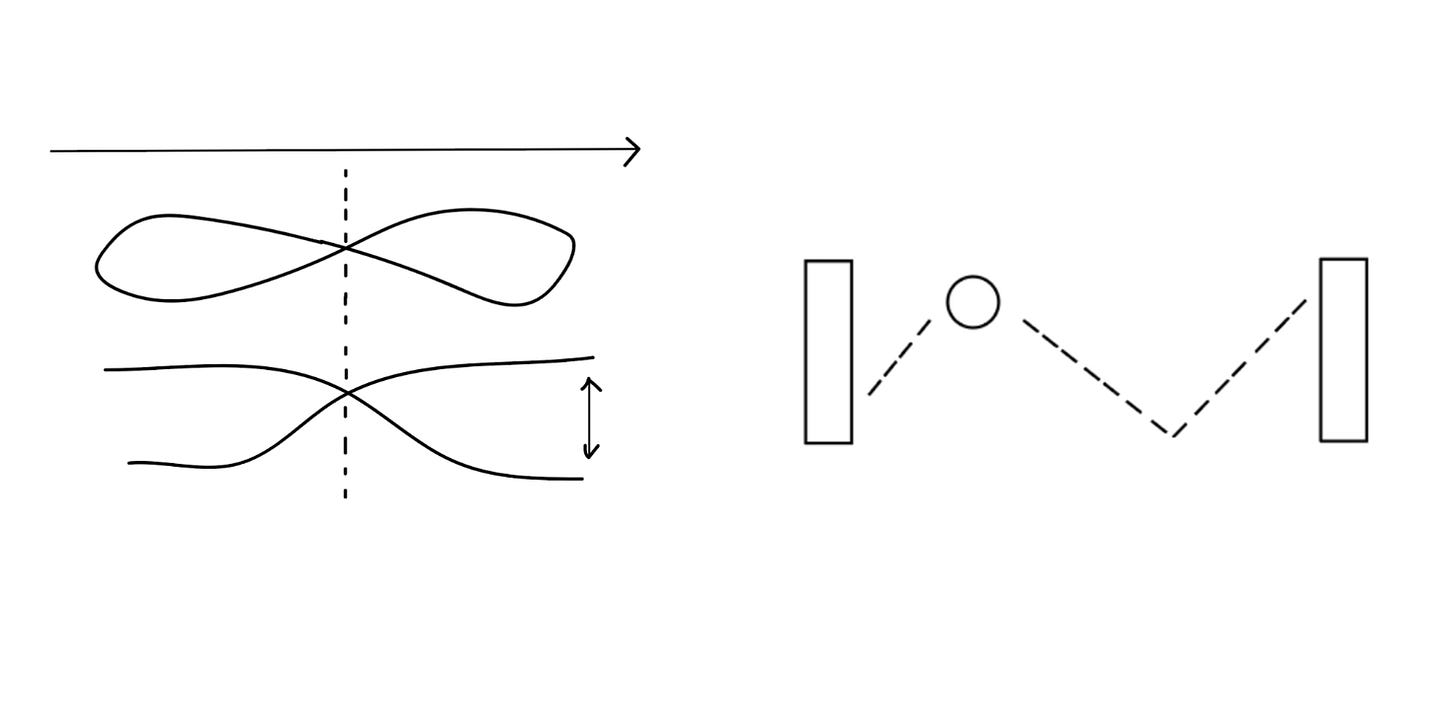

This could come from a literature structure in terms of the shape of content (leading principles/synopsis). For example, in Hong Sang-Soo’s film Right Now, Wrong Then, it was about a romantic story between two characters, and he filmed it twice. The direction of the story was almost the same, but the elements were subtly different as well as the end. And the structure of the film in my eyes would look like (left):

If I’m analysing the film in a linear way, then the twist would be the core structure of the film where, with this light twist, the story could end differently with mostly the same elements. And I can think about if the structure will loop back to itself like a Möbius ring. How long is the distance between the two ends under the Möbius ring in the graph? In this structure, you can reverse the order of reality, concept and fiction at your will. There’s definitely a lot more to talk about regarding that film but I seemed to be always more interested in discovering how a director/author tells a story, and this had become a playful hobby and has definitely influenced my perspective on making music.

In the text called conversation on my website, it was something that I used to think about when playing with other musicians as well as talking to other people (above right), that ‘conversation to some extent is very close to ball sports.’ In badminton, a high toss seems to make it easier for the opponent to catch the shuttlecock. With careful attention, it may be possible to prevent the shuttlecock from landing. In baseball, the ball seems to travel in a more direct manner. What factors affect power and speed in this sport? In a simple back-and-forth motion, time appears to be related only to physical stamina and the size of the shape. Well, I’m getting a bit over excited about mapping the elements of the sports and conversational interactions to each other.

I think there is similarity in recognition between these and graphic scoring, where you always seem to have to register yourself or your instrument as a point, symbol or initiate yourself before developing to any more complicated stage - graphic scorings are more like a preset for understanding or more like reference rather than the topographic structure I was trying to write about, which happens more naturally in a intuitive way after the improvisation, and it doesn’t come up all the time. The funny fact is I never ran into any graphical intuition when I was playing with Shang as Oishi, the reason could be our music is changing all the time, or maybe I can actually summarise our ‘structure’ as white noise, which is apparently still recognisable after deformation [laughs]

KP: Yeah. So along the way you mentioned even more instruments than what I saw, you've mentioned strings, guitar, is there something that you’ve been searching for as you move through these instruments? Is there something of a throughline that you see through them?

ZH: I think they are now partially like my kind of language system in terms of instrument but I'm still practicing them as for example, I also want to do jazz improvisation and I think they require a certain amount of techniques or certain amount of experience to play with other people without explaining too much. Just generally I don’t think I could be as expressive on traditional instruments than on electronics. And I sometimes found that limitation for playing with other people too. In my experience when playing with other people, sometimes people are very expressive, then I found myself lack of the ability to be as expressive as I wanted to be in the same harmonic language on say guitars and bass guitars… it’s a frustration that I'm facing. And maybe that’s somehow part of the larger reason why it stopped me to play with a larger group. I wish to have the full experience of the enjoyments in different perspectives as well as the challenges. And this expectation could probably be the throughline. Which is why I'm still practicing because I also wish to be able to select what to play in both texture and musical way. Also if I were to start playing with other people in this way it would be another new practice, apart from kind of professional music therapies and Oishi sample collage. It would be another side of a musician I guess.

KP: Yeah, and there can only be so many sides. Yeah I guess, just wrapping back around, since you're making music right now in London, you have made music in China, would you compare the two communities in any way, as far as being good for your musical development? Like what are some things the UK gets wrong, gets right, China gets wrong, gets right?

ZH: I think because I wasn't very active when I was in China and I only played a few gigs before I left for London but… what I immediately feel in London it's… you get to choose so many different ways to play music where the audience is same level of critic. Say I play at Cafe OTO, you get the most serious and critical audience in the world, in a good way. But I think the experience in China is they’re more like a group of people, which I feel like is always the same group of people. In London there’s endless musicians where you can see them every night with different people and they have different connections. In this regard I would say the style, or the style that’s more popular in China, seems a bit less diverse than it is in London and somehow it’s only when I came to London that I feel like I could use so many different materials or express in so many other ways. Or maybe that is just in general that I didn’t really have enough experience before. That this would eventually come if I were to develop my experience as a musician. The ideas of the Beijing scene, I think it's a bit hard for me to answer that question, cause, yeah… I would maybe prefer not to comment on that.

KP: Yeah yeah yeah. Well is there anywhere else that you wanted to go, anything else that you wanted to talk about? I guess, other than the harmonica setup and other stuff we talked about, are there some directions in sound that your interested in right now that we haven't touched on?

ZH: Currently my practice is for the kind of music psychoacoustic pathway, I kind of wanted to go a bit further than harmonium, so I was trying to do this duo project with Li Song, if you know him - I think he was from Beijing but he has now been in London for four or five years - he’s a computer musician. We had recently started a duo, essentially trying to explore something related to binaural beats as well but I played strings and he actually played snare drums with a sine wave and laptop. Doing binaural beats. The idea is to have some simple… maybe I would just play like three notes but the sine wave would have this difference, 5hz difference from the frequency that I played on guitar and we might continue that for like forty minutes as a recording. So that’s the thing that I did for the psychoacoustic. I think other than that I am now playing modular synthesis to try to more build things from scratch. I've been kind of getting to the idea of… cause it's sometimes when people make music there might be judgment from other people saying, ah you are just making music in this genre. And then I would think about, OK what if I see myself from scratch. That I start to explore my music from zero. And then even though I still go to that music genre I can say these things are mine. Because I am not that interested in making new music or making really experimental music at the moment. I won’t call myself that, I'm not doing that. It's more about if I could I would definitely like to find this genre that I could stick to and play music or make music for that genre or for that style and maybe the music I make might be a bit different or the genre will change over time but I think it's always important to rethink about things. That’s also the things that I did with Shang as well is too try to be a someone that uses more languages, less concept. I think that’s working. Yeah, I think that’s everything that I'm doing now.

KP: So you mentioned that you’re doing beating music in an acoustic way with guitar and drums and you of course also have your electronic beating music. Do those feel different when you experience them?

ZH: It is different. The timbre is different but my preference, it’s to try to not have that much effects so the feedback guitar or the strings that I'm playing, it's always somehow similar to electronics. Why I started using harmonica for Last Day of the Cold, for example, I found that if I play the highest pitch that I could play on harmonica consistently it actually sounds like a continuous sine wave, or feedback. I found that very interesting. It’s also the idea of, if the sound could sound beautiful or the sound could sound good why not use it. Why not continuously use it, as part of the repository? That’s how I started harmonicas. And that’s why so far I haven’t found that the electronics that I use are against the texture of my acoustic instruments. In a minimal way, if the output, they are both minimal, it would be the same thing. It could sound the same thing, as sine waves.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

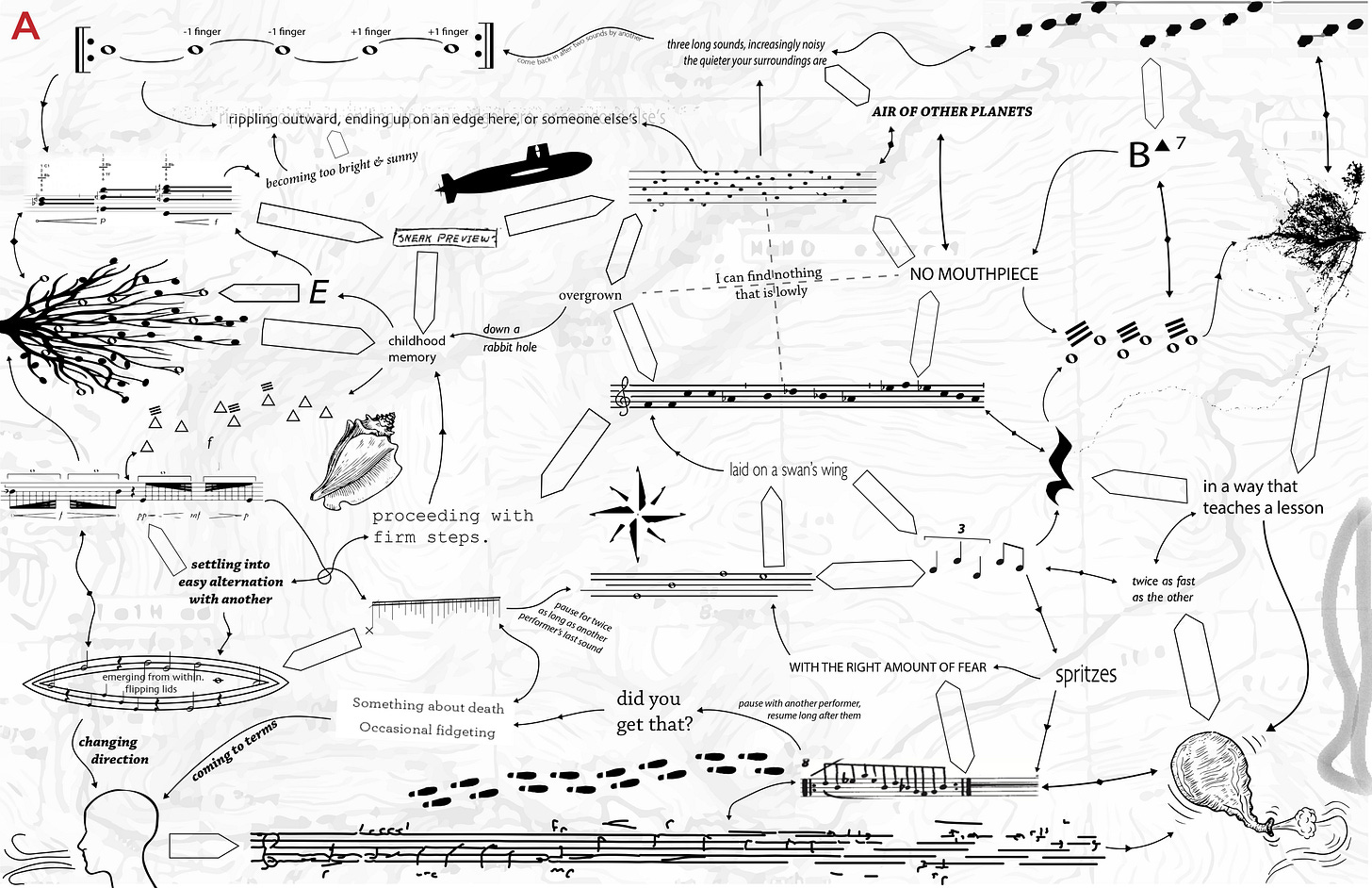

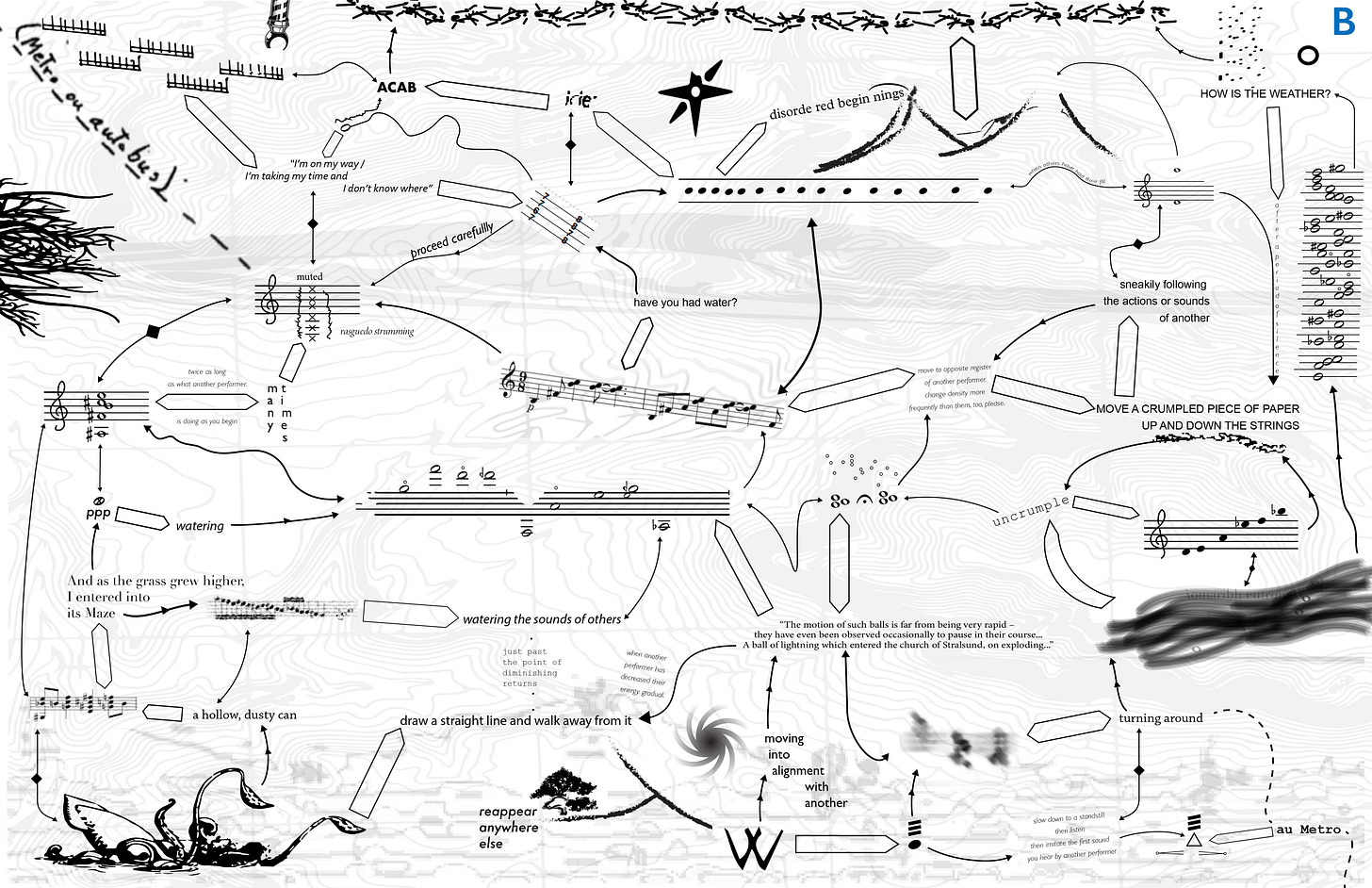

Ben Zucker - Repersonal Territories (Commonplace Collage No. 2) (2021)

Ben Zucker is a composer, performer, and audiovisual artist seeking new experiences through material mélanges who often plays percussion, electronics, and trumpet. Some recurring collaborators include Mabel Kwan, Eli Namay, and Adam Shead as Fifth Season. Recent releases include Semiterritory with Fifth Season, Vitamalisms/Revitalism with Third Coast Percussion, and the solos having becames and Aeroliths.

Repersonal Territories is a 2021 composition for saxophone or similar wind instruments and guitar or similar instruments with an open number of performers and duration. Each page maps regions of standard notation, fantasticized notation, realistic illustration, other symbols, and text both directly and obliquely directional. The border of each region features an arrow the kind of which determines the expression of transition between regions. The symbolic maps and the topographic maps they they overlay are unique to each page. Performers decide together where to start and how to end.

Whether players remain in comparable areas of the page or choose another path, the symbols and distribution of arrows unique to each page would seem to ensure interactions more complementary than corresponding. Each player must choose their instrument and how to interpret their page through that instrument independently though certainly with influence from the other, negotiating only when it begins and when it ends. The strong presence of dualisms - in standard and non-standard notation, realistic and fantastical symbols, direct and oblique direction - and an emphasis on transitions centers communication between two things. It all sounds like a healthy personal relationship, moving together and freely no matter where each is or is going until each decides it ends. Because when standardization collapses and expectation relaxes music and relationships are both just sharing and shaping time with each other.

Repersonal Territories was commissioned by Brian Ellis and Jonathan Hostottle. Here Ellis and Nathan Smith perform distinct realizations of two possible pathways with guitar and bass clarinet below.

reviews

Andrea Belfi - Eternally Frozen (Maple Death Records/Bow, 2023)

Andrea Belfi, Robin Hayward, Elena Kakaliagou, and Henrik Munkeby Nørstebø perform five Belfi compositions for percussion and synthesizer, tuba, horn, and trombone on the 36' Eternally Frozen.

A monkish vocal chorus anchors the opening "Pastorale" and its poignant intonation heralds a bittersweet emotivity brass carries throughout. Synthesizer as well, often an extension of the horns. Variations on canon form expand, reduce, and rearrange the echo of the trio with different effects on mood too: amassing in resounding triumphant fanfare; fading to leave the last voice forlorn; or a less linear assembly that can lend a sense of simultaneous stasis and drift. Percussion colors to complement the rest, as in shimmering cymbals alongside radiating brass, but more often lays a foundation of mesozoic rhythmic loops from low skins that lends weight to winds' bellows and volume to the canon constructions. The heart of it seems to be an earnest exploration of the effect of different voices' placement on each other and the effect of their sum on the listener, discreetly wrapped in a kind of song.

- Keith Prosk

Ensemble Dedalus / Ryoko Akama - ELIANE RADIGUE (Montagne Noire, 2023)

Didier Aschour, Cyprien Busolini, Thierry Madiot, Pierre-Stéphane Meugé, Christian Pruvost, Silvia Tarozzi, and Deborah Walker perform their hepta for guitar, viola, trombone, saxophone, trumpet, violin, and cello and Ryoko Akama performs their occam for ems synthesizer from Éliane Radigue's Occam Ocean on this hourlong record.

To repeat it in another way, the rhizomatic system of Occam Ocean often seems much the same, long performances of long tones to cultivate harmonic interactions, and always different, in how each piece expresses the limits of the instrumentalist, instrument, and their relationship. This is the first release of a hepta that, while the orchestral Occam Ocean exists, carries a special density compared to the often smaller groupings of the system. And Akama's Occam XX is a singularly electric entry in the otherwise acoustic system. An explicit goal of this record is to contrast and indicate the breadth and the depth of the system.

In the austere architecture of a single crested orchestral swell from seven, infinite laminae, teeming beatings, and psychedelic textures. Low oms. Wah wah. Yawning tanpura. Punctuated by brass yawps and the valve release of circular breathing. Towards the center of the structure's curved profile at the confluence of their movement they suspend a single sidewinding stream among them in their interaction, to return to something similar as the beginning in the end in deltaic diffusion.

Played in a minimal way the modulating synthesizer seems a faithful translation of electricity itself, the rhythm of current. Maybe my ear silos sound or maybe its a common human illusion but its layers appear in three distinct bands. Rolling low. Something in between. Siren high. Subtle movements shift the behaviors of bands and even appear to reverse the relative periodicities of them, low as fast as what high was before and in the suite of them shifting together the high so fast as to smooth towards an undulating curve. Punctuated by a kind of sonar blip, perhaps wave turned click, teasing the limits of audibility like the bands, breaching only for a beat.

The hepta shows the one of many; the occam shows the many of one.

- Keith Prosk

Francisco López’ 1981 through 1989 (self released, 2023)

"For nearly a decade, starting in 1980, I worked almost exclusively with walkman recorders and cheap cassette players. From the beginning, sound recordings were intuitively for me "worlds in themselves," always markedly different from the original "reality," always full of their own thrilling features. I developed my own, very simple -but very efficient- techniques for sound transformation using only cassettes. I couldn't afford the prototypical "experimental" tools of those times: reel-to-reel recorders, synthesizers, rhythm boxes and the like. With hindsight, this limitation turned out to be a great advantage and an important lesson, that has remained vividly present for me until today: the most essential tools are spiritual, not technical." - Francisco López

Although Francisco López recorded and created quite a lot of music through the 1980s, not much of it saw its way into the light until recently. As of 2023, releases spanning every year from 1980-1989 exists on the artist's Bandcamp, each release re-edited and re-mastered for modern ears. They're intriguing on their own, as obscure outsider primitive tape experiments that seem to have a totally different identity to the rest of the era's tape culture. But they're even more exciting when viewed together. They present the sonic story of a truly original artist finding himself, growing, experimenting, and creating an aesthetic that would become the blueprint for his next 3+ decades of work. It makes it clear that some ideas were found along the way, while others were there all along.

1981-83

1981-1983 collects five barely audible spaces. It's the sound of interior ventilation, of soft wind, of humming refrigerators, of static left in the tape machine, of something larger and fuller that's been near-entirely erased. Each piece has a slightly different soft, zen charm. They are uncompromisingly minimal, but not off-putting, comforting actually. It's like a single element of a room's soundscape zeroed in on, something you'd barely even notice given full focus. When listening with headphones it can feel kind of wrong for this reason, like these sounds should have been left in the background of wherever they were found, but at the same time it's this extreme focus on very little which is responsible for that lovely, warm, curious, meditative effect that leaks out from the speakers.

There isn't much variety to these pieces, they all share a focus while presenting their own hidden soundscape. But the tracks are remarkably ahead of their time – this type of sonic, pure, non-performative minimalism had no precedent in 1981, and these tracks laid out subtle sonic ambitions that López would continue to follow for the rest of his career.

1983

1983 starts loud, with the sounds of bleeping and crunching radios, malfunctioning recorders and immense, swirling background static. It feels complex and paranoid, like a massive early communications system that's failing to operate during a blistering winter storm, that's passing through harsh squelching and static blurs instead of the intended messages. There's twirling high-end frequencies which are almost beautiful, but the fragmented, ruined voices that rest underneath obliterate any feeling of comfort. It has some progression and clicks and twists, but it never strays from that bleak, claustrophobic sensation.

The second track is softer and more mellow, but that claustrophobic sensation remains. This time I'm hidden under floorboards while something terrifying stomps overhead, or I'm stashed away inside a creaking metal drum that's been loaded into the back of a van. Either way, 1983 presents the most evocative music López had made yet. It showed that now that he had learned how to manufacture sonic realities, it was time to fill them with emotions and personality.

1984

The first track of 1984 dips into slightly more obvious environmental material, but at the same time further strips it from any reality. There's the sound of wind, water, cars, lots of easily recognizable elements of day-to-day life, but their assemblage is completely bizarre – and the fact that they're so recognizable just makes it worse because it leaves us with an alarming sensation where sounds we know are heard existing in a context that's thoroughly unknown.

Other tracks fixate on a single, manufactured, unplaceable hum that land in similar conceptual water as the early compositions from 1981-1983 – but this time there's more complexity to their soundscapes. They feel structured and layered, taking deeper advantage of the artificial nature of the recordings to make a more deeply artificial environment. Rather than sounding like an AC unit or wind, it sounds more like... well, it doesn't really sound like anything, nothing that exists on our world at least.

These tracks are another significant step up for Francisco López – there's aesthetic innovation, but advancements being made in the conceptual territory as well. The soundscapes are more richly fabricated than ever, they're surreal and inexplicable, and the "worlds in themselves" that they present are becoming full of strange and exciting characteristics.

1985

The compositions of 1985 are bleak and singular. The album opener is another frozen soundscape, but this time overflowing with deep bass and sonic dread. The effect is even more powerful when the second track kicks in with a dense wall of uncontrolled distortion. It's not completely unlike other rudimentary noise music from the time, but it maintains this pseudo-natural sensation of environmental chaos, of real-world hellishness. It makes the music off-putting and affecting.

The lengthy final track is a stand-out, a slow-moving and slow-growing drone of bassy winds that interfere and show their true colours with time. There's a deep thud that underpins it that sounds electronic, like a controlled crunching. As I focus on that I begin to question the higher register sounds, they hang still like involuntary tape static. Soon enough, without the track having even particularly changed, I've lost that wind sound I've heard before and I've realized I'm somewhere completely artificial and unknown. It's one of his more remarkable and successful experiments with duration from this era.

1986

The first half of 1986 is a rich, dynamic field of noise. It presents screeching winds and animals and maybe even people side-by-side into a meticulously shared cacophony that's as expressive as it is strange. Like in 1984 there are recognizable sounds forced into an unrecognizable context, but this time instead of being accomplished through a sporadic assemblage they all exist in a unified environment that continuously bends and shifts as elements come and go. On the surface level it may sound like a single mammoth of bassy static, but with attention all these little real-not-real nuances shine through.

The second half is a relative opposite, it's soft and mysterious with its subtleties laid out plainly. It's a delicate wall of bass with a trebly gust of air that perpetually sounds. The bass grows, becomes huge, arresting, all-encompassing. It reminds me of that claustrophobia felt on 1983 but now he's captured similar feelings with much less. Even when the track begins to remain still the bass still feels as if it's in constant growth – it's an effect that comes from the precision of certain sounds and the evocative juxtapositions which come from the other elements within the soundscape, something that López was getting better and better at during this period.

1987

1987 is arguably the strongest and most cohesive of Francisco López's 80s work – making it not a big surprise that it's received a CD release by the Dutch 'Universaal Kunst' imprint. 1987 presents a single, long, enigmatic track that demonstrates the earliest stage of López's fascination with extensive durations which has played into many of his compositions since.

The piece delicately juggles a large array of decontextualized environmental material. As the piece spends its first several minutes expanding, growing layers, and morphing into a large-scale impossible environment, it asserts early on that to guess at the source of these materials is neither worthwhile nor the point of this music. Rather than just gradually growing and losing layers, which it does do, the piece also features some stark and sudden changes, such as a moment where the high-ends cut out entirely after the piece had become somewhat comfortable – a harsh reminder of the artifice of the environment and of the artist's control over it.

The second half of the piece is largely about its descent. It slowly strips itself of its clearest and most defining elements before leaving a soft, bassy husk to decay even more slowly. It's careful and intricate, and evocative in how it strips something large and dense into a cold monotony before eroding it completely. It's also predictive of the radical long-form music and slow-fades he'd incorporate into compositions over the next couple decades.

1988

1988 was one of Francisco López's most minimal outings yet and laid out some early groundwork and ambitions for the ultraminimal electronic, or lowercase, scene of music that would start growing a few years later. It approached this idea of sonic lessness from a different direction on each track, both carrying an innovative new approach that would become a major part of his aesthetic into the future.

The first track makes use of extremely limited and specific dynamics. Almost all of the sound is within the sub-bass region, pushing a bulk of the sound into an inaudible range that can be felt but not heard. Higher register crackling sounds play out like accidental run-off from the throbbing wall of deep bass and will vary greatly based on listening device – carrying the effect that maybe the speaker is generating them solely because it's failing to reproduce the rest of the soundscape accurately. A tone enters and exits this piece, again using a limited dynamic range that has it float not-so-high above the rest of the sounds. It's a beautiful, single, elongated moment that pulls the whole piece together, makes it into more than just a semi-audible stagnation.

The second track focuses on sonic decay and degradation, honing in on this concept even more than the second half of 1987 did. It begins with the sounds of popping, degraded tapes that fail to pass through any information, and they slowly but surely ruin themselves until only a frail hum remains. Like in the first track, this one also makes room for a soft drone towards the middle, but this time it feels more like an element of the amorphic decay than a pleasant surprise, especially considering the stagnant near-nothing that exists on the other end.

1989

1989 presents one last significant leap forward in Francisco López's aesthetic for the 80s. This one includes denser, more dynamic, and more processed sounds than ever. The first track begins with richly reverberating percussive timbres, like a pulsating machine in a large concert hall. The reverberation twists and grows, the processing of the sounds shifts and settles into softer territory as the throb dissipates into the air. But the machine stays softly present until the end of the piece, even as its form completely changes.

The second track is a final meticulously rendered bassy throb that shakes though a gentle wind. Conceptually it's not so unlike some previous tracks, but this time the sounds all feel so careful and precise and clean. It's more calculated and ultimately more effective. It's not exactly crushingly dark but it's not so pretty either, it just exists as a harsh kind of environment, a recording of an uncanny phenomena from an imaginary place. Again, that's not a new concept for López at this point, but this is one of his most believable attempts at it yet.

1989 is a strong end-cap to Francisco López's 80s work and a clear aesthetic end to an era. At this point his tools and technologies are evolving, and his early primitive phase is wrapping up. In just a few years he'd begin releasing some of his most notable and influential CDs, such as 1993's Azoic Zone and 1995's Warszawa Restaurant. These early releases may not have left a string of influence like those did, they weren't even readily available until recently, but what's exciting about them is that you can see the obsessions and fascinations that made those later albums possible already on display here: the disconnect between recordings and reality, the constructed sonic worlds, the experiments with duration and stillness, the limited frequencies and elaborate filtering. But even despite that, these early works make for strange, evocative and thought-provoking listens – there's much to enjoy in this sparse, primitive, low fidelity strangeness.

- Connor Kurtz

Gabi Losoncy - Lieutenant (self-released, 2023)

"I want you to tell me what you think about. I want you to tell me what you think about me but also what you think about other things, and anything that you think about that you don't think to tell other people, and I want to know how you feel."

Ever since I was a child I had an intrinsic knowledge that the world centres around me. How couldn't it? Everything I've ever experienced has revolved around me, everything I've ever perceived has been seen through my eyes and heard by my ears. It's my own emotions that shape how I respond to the world around me, not anyone else's. And I don't have to put in thought or rely on clues to understand how I feel or what I'm thinking, I just know these things. I feel how I feel and I'm thinking what I'm thinking. I can't say the same about anybody else however.

A lot of my adult life was spent trying to forget this, to think less selfishly, to listen to and observe others and to understand their thoughts and wants and how they relate to mine. I remember being taught to treat others the way I'd like to be treated myself, but eventually I learned that that wasn't quite right – the way I'd like to be treated isn't necessarily the way you'd like to be treated, the way I react to things isn't necessarily the way you would. So in reality it's more like – treat others the way they'd like to be treated. It's something that requires attention and understanding, to know what someone else thinks and to know how someone else feels.

Gabi Losoncy's new record, allegedly her final record, begins with a plea to understand another human being – maybe a loved one, maybe not. She understand how she feels and she knows what she's thinking fully, like we all do, but for this other person she can only see or understand a fragment of them, the thoughts that they've shared and the feelings she's observed through clues like words, body languages, gestures and actions. It's a plea for a total understanding, to know the entirety of someone else's thoughts and feelings in the same way that she has total access to hers or that I have total access to mine.

I understand and admire this plea. It sounds modest but it's anything but, it's the biggest thing you can ask of someone, the purest intimacy. I'm not sure it's even a real possibility. But I too would like to bridge this emotional gap that separates us. I want to know what you think and how you feel – not just about me, about everything. I already know how I feel about all of these things, but knowing how I feel isn't so exciting for me. I don't like being the centre of my world, I don't think I deserve to be – I want you to be there too. I want everyone to be.

The music that's present on Lieutenant isn't going to surprise any fans of Gabi Losoncy's work. It's like posting yet another selfie to Instagram – it still looks like the same person, they're just a little older now. I'm not even sure what can be said about the music, it's all a seemingly careless rumbling, like a microphone left in a pocket while the artist walks and moves, the amplified sounds of a shaking purse, or a contact mic attached to a bed sheet during a sex act. It's kind of inexplicable, but it feels to me like this is Gabi answering her own prompt – this is her sharing her thoughts and her feelings using an aesthetic that makes sense to her and that she can express herself honestly within. The catch is that even when laying it out like this, I still don't know how she feels or what she's thinking. I think that's just how it is though, maybe we aren't meant to fully understand anyone other than ourselves, maybe the way we think is so different that even if you did tell me every last thought I still wouldn't have access to the full picture in the same way that you do.

So we rely on clues and on words. We ask questions and we observe reactions in an attempt to understand. "Do you like it?", Gabi asks towards the end of the single-sided LP. I don't think it's a question for me, and I'm not sure what "it" is, but it's a question that runs much deeper than simple curiosity. It's another plea for understanding, to truly understand how someone else feels, to hear what they're thinking. If we're unable to connect our brains to another human being so thoroughly that the full extent of their thoughts are immediately clear to us, this communication is the next best thing. So I'll continue to look for the signs, listen to your words, and observe the context clues that tell me how you feel and what you're thinking and who and how you really are. Even if my world is stuck revolving around myself, it doesn't mean that with some effort I can't see your world as well.

- Connor Kurtz

Lionel Marchetti & Decibel - Inland Lake (le lac intérieur) (Room40, 2023)

Louise Devenish, Cat Hope, Stuart James, Lionel Marchetti, Tristen Parr, Lindsay Vickery, and Aaron Wyatt perform two collaborative compositions for percussion, flute & ocarina, piano, electronics, cello, bass clarinet, viola & violin, and radio on the 38' Inland Lake (le lac intérieur).

A sound narrative seems to take the lead-footed diver's path, rim to rim along the lacustrine profile. From crystalline resonances and quavering breath, the glinting surface water and the fetch that ripples it, some insect hovering over it in coarse nasal buzzing. To synthesizer's abyssal atmospheres, sonar songs and morse beats, radio transmissions clipped in the deep as if picked up in outer space, darting strings like fish unwittingly caught in light that shouldn't be there, seismic rumbles, moments of stillness as settled as silt. Its narrative circle and trough recalling the waves its more resonant sounds do, two forms of the same thing like the blurring of acoustic and electric, natural and constructed, ensemble and composer, the surface and the deep.

The brief epilogue a reflective glimpse in chirping dyad against a celestial backdrop.

- Keith Prosk

oishi - once upon a time there was a mountain (Bezirk Tapes, 2023)

Ren Shang and Zheng Hao play two tracks with sampler, recordings, and other electronics on the 30' once upon a time there was a mountain.

Leveraging the cassette format, the presentation suggests a continuity and divide as alike as walking up and down a mountain, on different faces or even with the new view of what was behind you before ahead of you now. One is hum, whirr, chitter, crackle, clips of radio, impressions of concrete scenarios in voice, footfall, and wind. One revs and rumbles like an unmuffled combustion engine, with country western crooners cutting in. While the second evokes it the first references the more rural Illinois in its recordings for a kind of road story, the mundane modern odyssey in search of identity, fit for a debut. Bucolic signposts in original audio and obliquely associated mimickry color the minimal sounds around them, that could carry any meaning. What was next to nothing before reinforces the fantasy only in juxtaposition to the brokedown building blocks of concrete and musical sources. Once upon a time there was a mountain but the weather wore it to dirt to be a bed for cultivation where before it would not grow.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for sharing time with harmonic series.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $6.35 to $8.47 for February and $4.42 to $5.89 for March. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.