IM-OS, Issue #10 is available, featuring notation from Henrik Ehland Rasmussen and Laura Toxværd and the essay Rating Degrees Of Openness In Experimental Repertory, Part I from Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $4.42 to $5.89 for March and $1.95 to $5.19 for April. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.

conversations

Jessica Pavone and I talk over video chat about writing for solo and for ensemble, different kinds of time, feeling good and sounding good, resonances, current interests and future work.

Some recent releases include Images of One with Tristan Kasten-Krause, …of Late with the J. Pavone String Ensemble, and the solo When No One Around You is There but Nowhere to be Found.

Jessica Pavone: Hi!

Keith Prosk: Hey! Good morning. How're you doing?

JP: Good, how're you? It took me a second, I don’t use Skype really so it took me a second.

KP: No worries, sorry. I mean, I was using Zoom but then they started charging for meetings over forty minutes so… I'm cheap like that [laughs]

JP: I wonder if I should use… cause I use Zoom to teach and most of my lessons are half an hour but some are longer and usually if Zoom cuts us off we just relog in.

KP: Oh gotcha.

JP: I wonder how this is with audio though. The reason why I use Zoom is I teach piano, the audio is better.

KP: Ah yeah I mean I don’t have to deal with actually good sound. I just have to catch your voice.

JP: Yeah. Facetime actually works really good with audio for some reason. I use that sometimes if Zoom isn’t working. Anyhow… I've used this like twice this year. Well here we are…

KP: So you’re a piano teacher as well, are those still mostly… I don’t know if New York has mostly returned to normal… are those still mostly on Zoom?

JP: Well what happened with me is I had a combination of people. I was traveling to their homes, I was traveling to people’s homes for lessons before the pandemic and then so when the pandemic happened I taught on Zoom for two years. And in that time my business just built up so much and also I got more students that lived closer to me through advertising and stuff that I got to the point that I'm not traveling. You either come to me or… stay on Zoom or quit. So a lot of the people that I was traveling to just stayed on Zoom. They’d rather not come to my house. I would say I teach like twenty students and maybe five come over and fifteen are on Zoom. And the ones who come over are the ones that… once everything opened up I started getting new students last fall. New students that I acquired since things opened up have been coming in person who were never on Zoom but the ones who did Zoom for two years just stayed on Zoom cause honestly it works fine and I think they don’t wanna go anywhere and it’s also a lot to have someone come into your house. Like it’s disruptive, I'm coming into your house and there’s small talk and all that shit. I just got it to work so well that a lot of people just stayed on it.

KP: Yeah there’s definitely that efficiency around the commute and small talk and stuff but do you find that there’s something missing at all there?

JP: Well I mean I did it for two years straight so I'm able to adjust my language… like I learned how to teach differently. I do think that there are some students that would benefit from being in person but I'm just teaching beginner piano it’s not like advanced shit. It’s just for the kids to have something to do after school, a lot of it, not all. A lot of it is just parents want to keep their kids occupied. Yeah it can be frustrating sometimes but I've really learned how to change my language to make it work. And I kind of like not having to… like I can do a workout and not have to shower and just hop right on the Zoom and teach, you know what I mean [laughs] I like it. I don’t like being stuck in the house all the time. I feel like the world opened up and I'm still living in my covid life.

KP: Yeah especially with Amazon being a thing now, you can just get everything delivered.

JP: Yeah yeah yeah and I never really got anything delivered before, that was like a whole new thing and I started doing that during the pandemic. I was like, wow this makes everything so much easier. I feel like I have a lot more free time cause I don't commute everywhere but I also live alone so I have to change my disciplines and change my habits to make it feel less covidy, like get out and take a walk first thing in the morning or get dressed. I make myself get dressed now which I wasn't doing before [laughs]

KP: Yeah yeah. I feel like students… one of my nephews, he started kindergarten on an ipad, getting taught digitally during the pandemic. I feel like one of the headscratchers there is that sometimes learning is so tactile like between writing or moving things or being with other people… something’s lost but I guess with piano they’ve still got their hands on the keys just the voice is somewhere else.

JP: Yeah and like if anything it gives them more independence because I'm not there to move their hand for them. They have to find the keys themselves and if I want to make sure they know I'll say like, point in the music where we are, we’re in measure five, point to measure five. I just have all these different techniques that I use now.

KP: Nice nice. Well yeah I mean I've got some things lined up… I apologize I feel like I've been especially scatterbrained lately so I might be looking down at my cheat sheet a little more than usual… but at any point please feel free to take it in any direction that you want. But yeah thanks so much for taking some time to talk a bit…

JP: Where are you located?

KP: Austin. Texas. We’ve actually got a very similar day to y’all, very grey and dreary, maybe ten degrees warmer but that’s about it. So, yeah, I feel like the two big threads in what you’re doing recently are the solo series on Relative Pitch [Records] and then the string ensemble stuff. And I think I've seen you say that you think of your ensemble stuff as an extension of your solo work and I'm assuming this kind of means that the kinds of things that you’re interested in doing with multiple voices on delay pedals, now you have the agency of people behind each voice…

JP: It’s more actually… oh sorry, finish…

KP: Oh, I guess I was saying how these solo and ensemble efforts are different for you, or how do you work with yourself and multiple voices on pedals versus multiple voices with people type of thing?

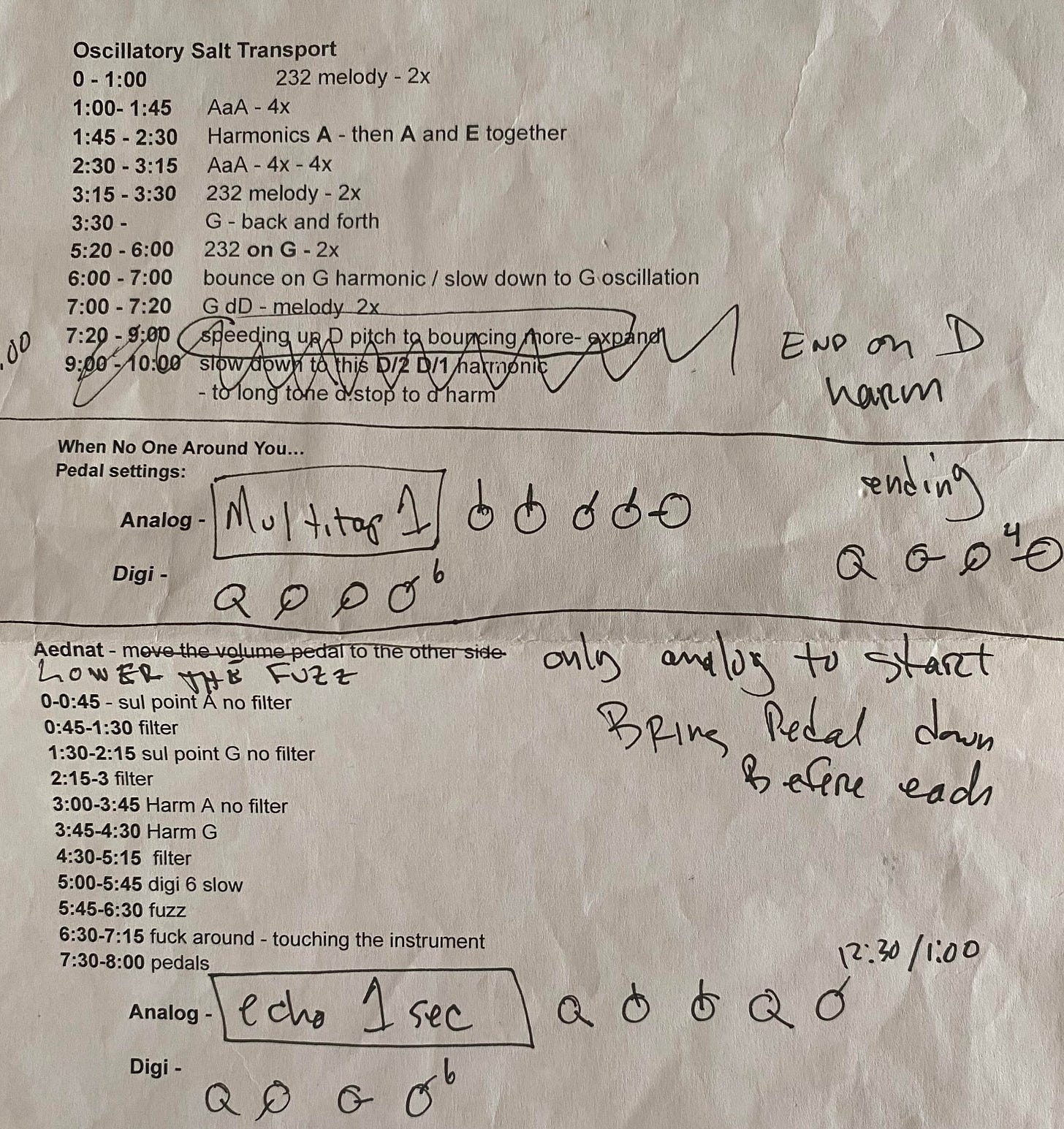

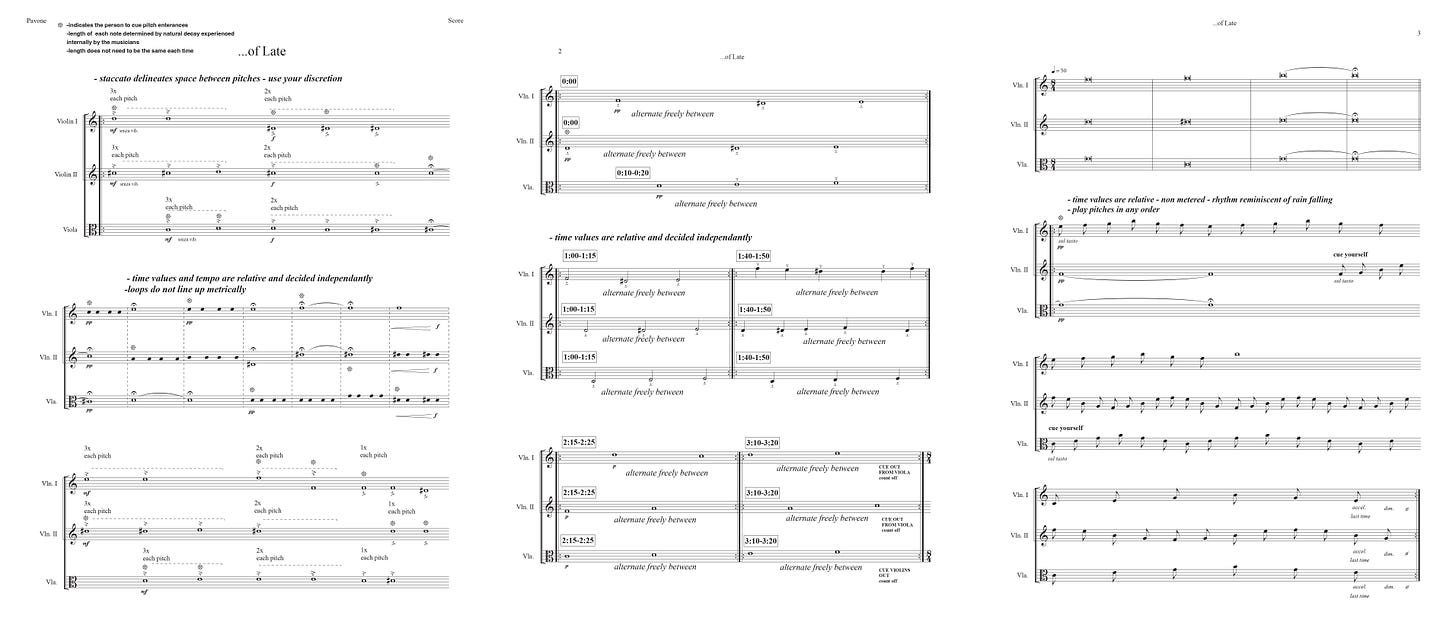

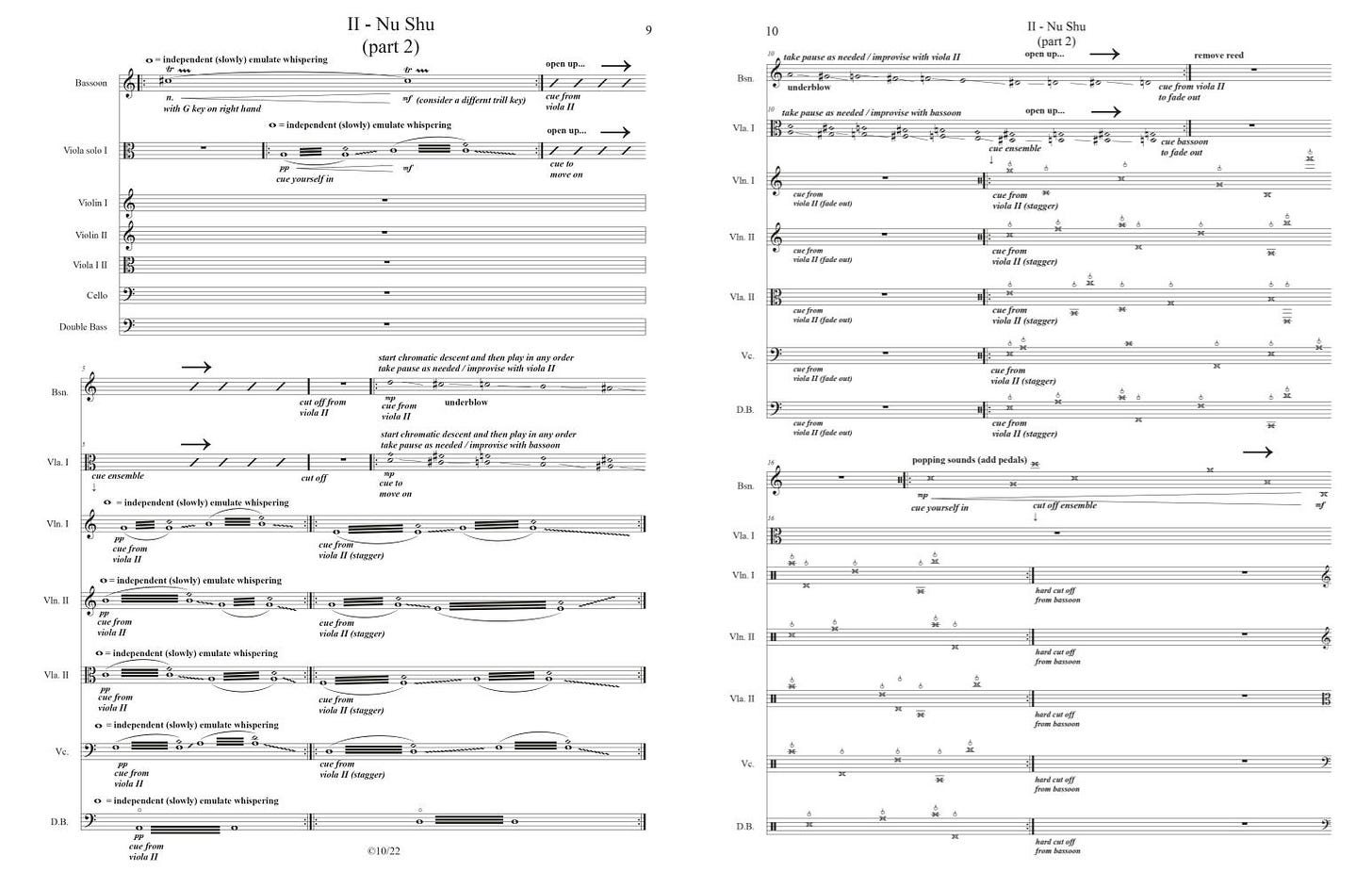

JP: I feel like it’s less about what I can do with pedals and more about how I write. I kind of really focused on solo music for a good five or six years and before that in writing music I notated music. I mean I do notate music but more traditional, with meter, more through-composed. The way I wrote music was more traditional and when I was working really intensely on solo music I'd kind of find a sound that I'd like to be in for awhile and figure out how to move to the next sound and I would use a clock. During solo performances I would use a clock and I would kind of have a series of… and when I do solo music I don’t write music I just write notes to myself… actually I can show you cause I have them right here because I'm preparing for a solo set. This is kind of what a solo score looks like I mean it’s scribble on a notebook for a long time but once I finish it… I know what that means, nobody else knows what that means, that’s like my little code but that’s the timeframe to move between these things, those are the pedal settings if I need them, and those are the timeframes. So what I really got from the solo music that I transfer… and I can show you some string ensemble scores because I think that’d explain it easier… is moving through the space not in metered time. So when I started writing for the string ensemble I kind of started approaching it that way, where I would make a time-based score and it’ll be like… there’s no way to screenshare here is there…

KP: I’m very technologically illiterate, I'm not sure.

JP: I have it printed out. I have scores. I know where they are. So but with the string ensemble music I kind of intersperse that with meter to give form. Also when you work with other people… for me I can give myself these directions and know exactly what I’m talking about so it’s kind of like, how can I take this but make it into ensemble compositions where I have to be more specific, so other people understand what I'm doing. Here’s just like an example, I don’t know if you can see it, this is the middle of the piece. There’s no meter, here we’re just cueing each other to play these clusters. See so this is not using the clock, sometimes it’s just cueing, sometimes it’s the clock, and sometimes it’s notation, and actually this is a good piece because it has all of it. So in this one we’re cueing each other so I take the bar lines out, right. And then here, see how we have these dotted barlines, so they’re holding a pitch while this person’s slightly pulsing and I write a note here like, it’s not metric just make slight pulses, and this measure can last as long as we want it to because I designate who’s gonna cue into the next one. Because the way the solo music sounds, it’s just moving through, so I kind of want the ensemble to just move through a sound. So we’re just moving through with these cues and then we get to the next page and we turn the clock on and then the clock is the conductor. This is something I do a lot. So here the violins come in at zero, viola doesn’t come in til... I usually give a time frame so that it’s like I can come in between 0:10 and 0:20, you know, so I can choose when to come in. And basically we’re in this cell and there’s a repeat sign but we’re just alternating freely between these pitches at our own rate and that’s how I get this swarmy kind of like long tone oscillating thing. So that’s what’s happening here. So I use notation in a sense, like here these are whole notes, these are half notes, these are quarter notes, but I wrote in the score, time values are relative and decided independently. So that just means you count to four in your head, like whatever this was, and all our whole notes are different lengths. And then we get here, it’s not necessarily a half note but half as long as the last one you did. So this just feels like it’s gradually getting faster, the oscillations are gradually getting faster and that’s my way of communicating. When working with other musicians they understand that half note is less than a whole and a quarter’s less than a half. So I had to figure out a way to mix notation with what I was doing with the solo music… and even you see here I give time frames, like 1:00 to 1:15, this one’s 1:40 to 1:50, so we’re not all changing to the next cell, so it gives it a gradual shift, you know. And then actually this piece goes from we’re cueing each other to this open-ended measure to just being in the time. So we’re in time-based score and then the next page I have these cues of these whole notes to get us back together… Yeah, there’s no bar lines in this it just says, rhythm reminiscent of rain falling. So the violinist is just playing around with these pitches and then these two come in and then we each come in, like we’re not together and we’re just sort of like playing. But there’s other times where I will… here’s one where I will be in that open space and then we’ll go into meter, like I'll put quarter note equals fifty and the clock, we can tell the tempo by the clock. And then like this isn’t a time-based score it’s more of an open-ended score but you see in the end we come together. I mix the two. I do have one, I'm trying to think, where we go between the two where we start metered, we open up, and we go back to metered, I use both in combination. Yeah, here’s one where we’re just in time-based in the beginning, just doing these glissandos, and then here we go into notated music to take it out.

KP: Nice. So when you say ensemble… Or, I guess your ensemble and solo kind of relate less with anything that’s in the sound but more so the kinds of ways that you play.

JP: Yeah. I'm not trying to recreate what I can do with pedals, I'm trying to open up what I can do with notation. Kind of figuring out a way to notate this, so that other people can play it. Cause really with pedals I try to use them sparsely. I'm trying to not actually layer myself, I'm trying to add another sound so I have something to play with, you know. I don’t know if that whole thing was confusing or if that made sense…

KP: Yeah, that all works out. And maybe this is a different flavor of the same question but I saw that on the recent Spam Likely there’s some electric stuff but a lot of times I feel like the electric stuff is kept solo and the ensemble stuff is kept acoustic, is there an actual divide there and is there a reason for that divide if it is there?

JP: Why Spam... oh I see…

KP: I guess solo and electric are kind of together and ensemble and acoustic are kind of together…

JP: Yeah. I don’t love working with pedals. I don’t love it. I kind of just do it to add something to solo music, just to… although lately I've been playing some solo sets without the pedals at all. Spam Likely, that was just kind of like we were fucking around. I think I did one side with pedals, one side without, I can’t remember, we did that so long ago. I generally don’t use pedals unless it’s in my solo music. I think maybe Matt [Mottel] was like, bring your… I feel like I only ever bring my pedals to play with other people when it's requested. I generally don’t… like if I'm gonna do an improv set with people I don’t bring them. Maybe I have in the past but I kind of use them less. Yeah, I'm just really interested in acoustic music right now. I feel like electronics adds a whole fuckin headache. But there’s also so many… I found that just doing solo music sometimes you can get the craziest sound acoustically on your instrument that you could with your pedals too. I like finding the crazy sound naturally. I’m kind of on the fence for my next solo record whether I'm gonna use pedals or not. I've used them in every one, I'm not sure. I'll probably end up… cause I have a very simple setup too, there’s not very much you can do with it. I feel like I've exhausted the possibilities. But I wanted that to be that way, how much can I get out of so little. Something else about the ensemble music, part of why I like writing in this way, where it's just like you have a timeframe and each person alternates notes in between, you’re gonna get some crazy rhythms and polyrhythms that if you wrote it out and you had to count it it’d be so fuckin exhausting. I have a thing against music where it’s counting like crazy to get this crazy sound and I feel like a big part of my music is that I want it to feel good for the players, I want it to feel good to play, I don’t want it to feel stressful to play, just because playing a string instrument alone is stressful. So I feel like when you’re alternating pitches and there’s almost no rules… it’s almost like putting structure to improvisation. The thing that’s great about improvisation is that things that you don’t know could happen will happen and with this clusters that I would never think to put together will happen and the rhythm… like if you tried to actually transcribe the rhythms that come out and you saw it on paper probably some pretty complex rhythms would come out and I prefer doing it this way than actually writing out complicated rhythms because you’re just counting and that’s stressful and you’re not in your body, you know what I mean. I’m trying to get the music out of the head and more in the body. And I think that’s another reason I write that way.

KP: Nice. It also seems like it’s really harmony-based and my sense is that whenever you’re dealing with stuff like that it’s nice to give a little bit of leeway to each personal clock as well as how the location feels, how people feel in that moment, if something nice is happening that hasn’t been possible before somehow then it’s given time to kind of dwell there.

JP: Yeah absolutely absolutely. And then the problem that I have with improvisation as amazing as improvisation is sometimes I'm just like, where are we going. Do we know what we’re doing. So it’s kind of a way for me to merge the two interests. Maybe indeterminate is a good way to describe it but I think of it more, because I come from an improvising background, how can we structure improvisation so we have the freedom of improvisation but it knows where it’s going.

KP: Yeah. I feel like a lot of the people that I talk to they don’t necessarily see that divide. A lot of what they deal with is kind of structured improv or maybe there’s flavors of both. Do you feel like there’s a culture in New York City or that you’re in touch with where there’s kind of that strict divide between the free improv crowd and the through-composed crowd?

JP: I don’t know, I don’t think so. I think it’s more just my different disciplines coming together, you know. Yeah it’s the things that I'm interested in. Cause I think composition can be really restricting and I think improvisation can be a little bit unwieldy. You know it’s more just via my background, I think I came to composition through improvisation

KP: So then going from solo to ensemble… in another interview you mentioned that you like to blow things up, I think do it the Braxton way was said…

JP: What do you mean by blow things up?

KP: Whenever it’s possible, and funding I guess is an issue but… kind of think of it in an orchestral way and I feel like we got a taste of that with Lull with the soloists and stuff…

JP: I just did another one of those.

KP: Oh nice.

JP: So you were saying that my two things that I do are solo and ensemble but that’s kind of the third thing. That’s something I want to do more of and that’s something that just takes longer because it costs money. But I did that piece, Lull, and I just did one I recorded in January it will come out in the fall. It’s for string sextet and improvising bassoonist and that’s another way of encapsulating people who improvise in that form but I cut you off but yeah that’s another… I would do more of that if it wasn’t so laborious and intense. I mean, I'm planning on doing it, I already have the idea in mind, I want to continue doing that as my larger ensemble work. Lull isn’t like a one-off; Lull is like the next thread of work that I wanna continue with.

KP: Nice. Can you mention the bassoonist?

JP: Yeah, Katie Young. She lives in Atlanta, she lived in Chicago for awhile.

KP: Oh perfect, yeah, makes a lot of sense…

JP: What’d you say?

KP: I said that makes a lot of sense, right, cause y’all probably met through the Braxton stuff…

JP: I actually met her before, I met Katie before she even went to Wesleyan. I met Katie in like 2004. I was on tour, I was actually on tour with the Dirty Projectors, and I played in Chicago and I had to get away from the tour and I met her with a friend and she let me stay at her house. Yeah, she was living in Chicago then. I just stayed at her house. And then she was on tour with her friends and they stayed at my house in New York around then. Yeah, I don’t know, we just kind of stayed in touch between Chicago and New York and then she went to Wesleyan. I met her before, before that but I've known Katie for… yeah my whole idea with that is like working with people who have really established solo languages, kind of like concerto for improviser. And so far all of the improvisers I've worked with are people I have real history with, like I've known for twenty years, so I know their language pretty well.

KP: Yeah so my hunch with Lull was that it was as much a playing with friends type of thing, with Nate [Wooley] and Brian [Chase], than anything necessarily sound result-oriented and I know you’ve played with a lot of different groups with a lot of different kinds of instrumentation, like Army of Strangers or something, but were the drums and trumpet more of a textural decision or partly a textural decision and more just having two people that you trust to invite in to this environment type of thing?

JP: I think when I was thinking about that piece those were two of my favorite solo improvisers at the time and I think I was also thinking a lot about drone and I don’t know if you know Brian’s Drums and Drones series… he’s done a lot with drone…

KP: I don’t.

JP: And actually the piece that I ended up writing for him wasn’t very drone-oriented. But for Nate it was. It was more just like… it was so long ago when I first decided it, I'm trying to think what I was thinking when I chose them... I don’t remember but I just really really like their solo music. At first I was thinking drone and I was thinking of Brian’s Drums and Drones. And Nate, I thought they would complement each other well… Brian’s piece kind of went in a less drone way. But yeah the piece with Katie, I wasn’t specifically thinking drone, I was just thinking… and maybe from the experience of working on Lull and seeing how that worked, it was more just what are your favorite… and that’s also how I approached Nate and Brian. I just said, Nate what’s your favorite note to play on trumpet. Like I said, a big part of my philosophy in writing music is I want it to feel good, I want the musicians to enjoy it, you know. So he told me his favorite note and I was like, how long can you comfortably play that note, and he’s like, eight, nine, ten minutes, if I push it I could do twelve. I was like, nope, no one’s pushing anything, I want it to feel good, eight minutes, that’s it, you know. There’s no reason to push ourselves. And then I just put it through a series… I just took that one pitch and put it through a series of techniques that he showed me that he likes to do. And then I just decided what the strings were gonna play around it. And then Brian, the same thing. I know Brian’s music a lot better. I went to his studio and he gave me a couple samples of things and I chose what I wanted to use. And with Katie, Katie was in Atlanta so, I mean we talk all the time, she just sent me videos. Also Katie and I did like a double solo tour together in 2013 and have played on bills together a lot so I kind of already knew what she does. But she just sent me a bunch of videos of things that she likes to do and I just chose the things I wanted and wrote the string music. That’s kind of my favorite thing to do right now, like when I write those pieces I write… like both of them have been four-movement works and the first and last movement are strings-only and the two middle movements are the soloists but I kinda maybe wanna do one that’s just all soloists because those pieces are so fun to write. But I'm such a form person I need to frame it [laughs] The record with Katie, the second movement is her solo and the third movement we both solo cause that’s what someone said to me after Lull. They were like, how come you’re not a soloist on this, and I was like, oh yeah. So the next one is called Clamor and movement two is just Katie and movement three is the both of us kind of in dialogue with each other.

KP: That’s awesome. As you start to move towards this more concerto, orchestral thing and making it a bit bigger than just the string ensemble what do you feel like that opens up that you can’t do solo or with the string ensemble other than just like adding colors?

JP: I mean the more voices the more… when I was working with the string ensemble I was like, oh I want to do this with lots of string players. I want bigger and bigger and bigger and it's just not financially feasible so I just took a chance and tried to get an octet together. The next one I did was a sextet, they’re getting smaller. But yeah I was like, this is crazy, what you can do if you layer four voices, what if you layered ten voices. Yeah that’s where the Braxton comes in I was like, more bigger bigger, I want one hundred violins [laughs] Someday I want to have a hundred-person string ensemble to write for, I think that would be amazing. And that’s also what comes from Braxton, the more I work with the bigger groups the more I notice how… I mean obviously influenced by Braxton but the thing that is influenced is that I like to give agency to all the performers, like Anthony. I mean obviously I wrote the music but particularly in this piece where basically we’re just cueing each other through clusters, I could have cued every single one but instead I assigned different people in the ensemble to choose. Clearly it’s my piece but I want them to be involved in the creating within a parameter, within a boundary, kind of the way Braxton does that. It’s like you have all of his music to work with but you get to choose how you wanna do it, that’s heavily influenced by him yeah. And I just enjoyed playing that music.

KP: Yeah. And you mentioned with the soloist music that you kind of let them do their thing or decide their thing and then put the string music around it, do you find that facilitates a different creative direction than having to come up with everything on its own? I guess… like the string ensemble music, you have something to build around rather than from the ground up.

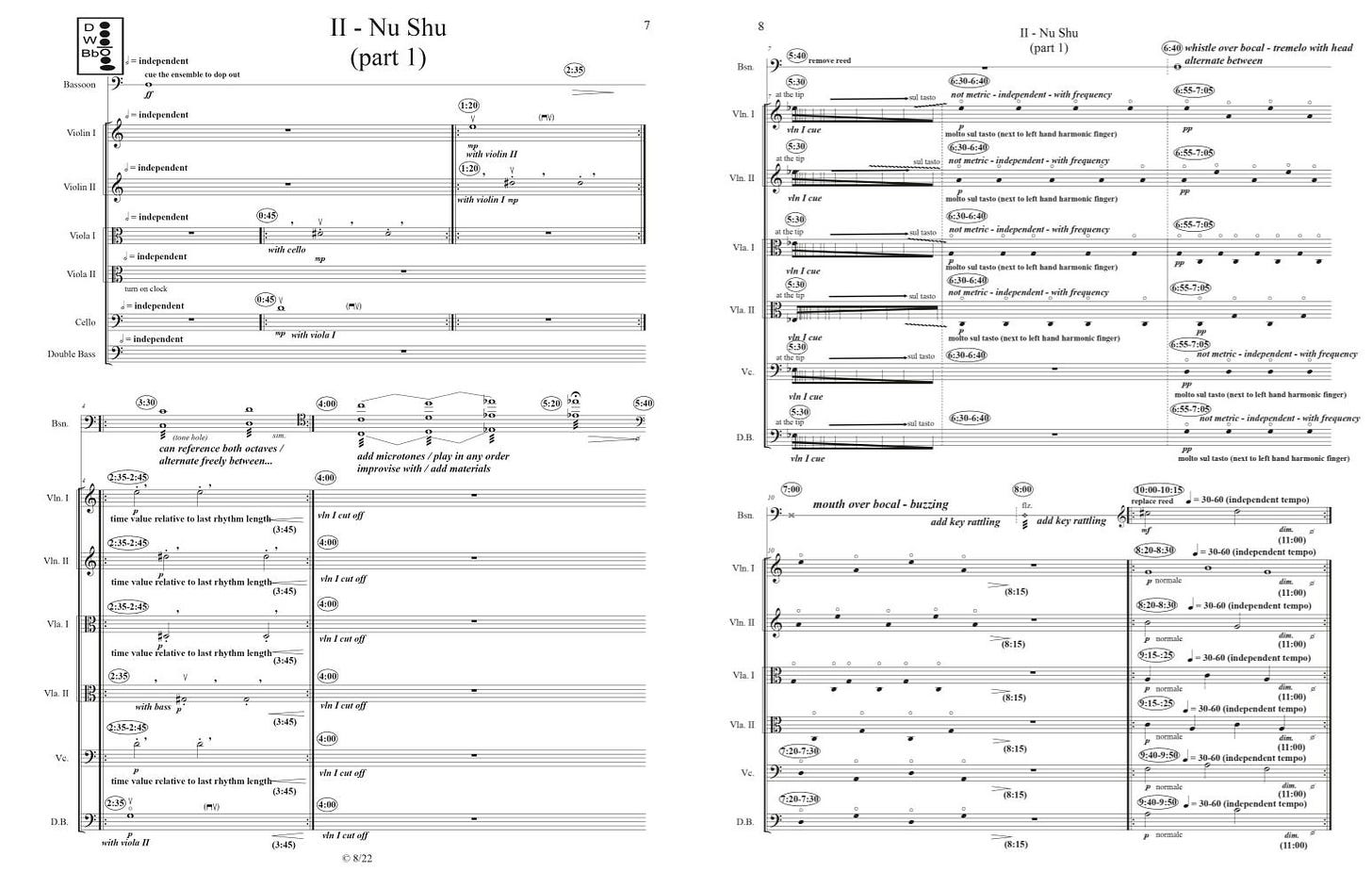

JP: Yeah, it’s totally different, it’s totally different, yeah. I can show you one of those scores too. Yeah it’s really fun. Maybe it does make it easier because it does like… but also cause I have to think about… like Katie’s playing some crazy thing on the bassoon and what I'm doing is like, how can I notate something to the string players that echoes that sound. I'll show you that score, it’s not all written over like this one is all crazy, I think I know where it is. I grabbed Lull also. This is Lull and this is Clamor, they live in the bags so I don’t lose them [laughs] they each have their own bag.

KP: Yeah it’s just a folio folded in a different way right [laughs]

JP: Yeah I had a composition student come over and I was trying… she was just laughing. It’s not disorganized but just trying to find my files in my computer. Also young kids know how to use computers better and she’s like, I don’t understand how you find anything. OK so, oh boy. OK here’s Katie’s movements. So you know with the soloists, the solo is on top, she’s just blowing a multiphonic. This is a time-based score. She’s blowing a multiphonic. These two musicians come in at 0:45, kind of accompany her, so I kind of gradually introduce… this is totally time-based, this is her doing the microtones, the strings aren’t doing anything crazy here they’re just slowly coming in with pitches but then on this page because we start to get into um… oh because she’s doing these microtonal tremolos here so it goes from her blowing a multiphonic, the strings gradually come in so that we’re all in a sonic space, she starts to move to playing multiphonic tremolos… I invented this, I don’t know if anyone... and I had to write instructions too… so this is just like play this note and gradually get slower, this tremolo gets slower, and I wrote, start at the tip and work your way… just gradually go from a tremolo to a single pitch. So she’s playing tremolo and then the string players pick up on her tremolo and then she drops out and then they gradually slow down and then they start ping ponging with these pitches, you know.

KP: Nice.

JP: And then she comes in blowing over her bocal and then we’re playing these harmonics like right next to the finger, you know. Sorry I feel like a crazy person.

KP: No [laughs]

JP: At this point she takes her reed out and her next sound is her whistling over the bocal, so for me to get the strings… so she gets that… there’s a lot of cross fading in this, the string players come in and I'm not sure how much you know about string playing but they're playing harmonics but they’re putting their bow on the fingerboard so it kind of sounds like whispering. So I was trying to get the string players to imitate her sound. It was cool for me to be like, OK what can I do on my viola that imitates Katie blowing her bocal, oh I can do this, how can I notate that for strings, I'm just gonna make this shit up… and a lot of it too we discuss it in rehearsal, like their input… I wrote this music but a lot of… I work with the same musicians all the time, their input comes into it. Like sometimes they’ll have better ideas how to execute something or we should make this section longer, I take their input. And then she’s just rattling her keys. And then this one, this one’s not a time-based score, it’s more we’re just going through cues and this is where her and I are soloing together. She’s doing a trill and I’m doing a glissando thing with going between the pitch and the harmonic back and forth. And so then we’re in this space, we start out but then we just open up, it opens up, and I put an arrow here like we start to improvise, so Katie and I are improvising together. And then the string players adopt what I was doing, so they start to echo me. And then the next thing Katie does, so Katie and I do this glissy thing together but then the next thing I want Katie to do, she uses pedals on this one, she has this crazy popping sound that she can do with the pedal. So before she came in with her popping sound I had the string players come in with these like muted pizzes to anticipate what Katie was doing. So I invented this, this isn't a real notation, I invented this, I just took an image and I write little words to explain what to do. Yeah, I don’t know, and then, yeah… I don’t know if it’s helpful or more confusing to look at the scores. These are Brian and Nate’s. I mean Nate’s is very simple, Nate’s is just a time-based score and we just move through, nothing, it’s really simple. But Brian’s, he taps on the drumhead so he’s tapping on the drumhead and then I have them doing like a col legno to a tapping, right, to imitate him. I don’t know, this one is also time-based. That’s a lot of information. I don’t know if you even read music, if it even makes sense. Do you?

KP: Eh, so I can typically tell what’s going on but I can’t read pitches.

JP: OK. But you can maybe see how textures are changing?

KP: Yeah yeah yeah.

JP: I think I'm a visual person, it’s hard for me to explain things without showing.

KP: No, no worries. So I know that some of your stuff is based on sympathetic resonances across strings, like your solo stuff. When you blow up to a string ensemble are you carrying that over, trying to find some overlap between like violin and bass? And I guess, furthering that, as you start introducing these new instruments you mentioned imitation but… maybe not a direct sympathetic resonance but is there some kind of resonance that needs to be there for you?

JP: Not as much, not as much. I definitely… I mean all of those solo records, all of the solo music is based on the notes of the open strings. Almost every piece is based on the notes C G D and A for those reasons. That’s another really strict parameter I put on myself, like how much can I get out of this one idea. It’s crazy, I don’t know how much more I can do of it. But I don’t think about that as much with the string ensemble stuff. I don’t think about the sympathetic vibration being one of the more important things. I think more about form and creating weird sound worlds. That doesn’t really carry over, that part about it. It’s more just opening up how I write.

KP: And then you also kind of sing and hum, so how do you feel about how those vibrations interact with those of your viola? I guess all sound is a bit locational in a way but voice is a little special in that what you're hearing inside your head is super different than what people are hearing outside of your head.

JP: What are you referring to specifically? I'm just curious.

KP: Maybe some of your solo stuff for instance, where your singing, or there’s a humming section on Lull…

JP: There’s a humming?

KP: I think so…

JP: There’s a string ensemble piece where there’s humming.

KP: Oh maybe it’s on …of Late.

JP: Yes.

KP: Oh OK [laughs]

JP: Yeah cause, yeah, earlier solo records I would have like one song where I would sing on. I don’t do that any more, I don’t like singing, I don’t like singing, I don’t like it. But the humming, Hidden Voices is the name of that piece, yeah, I thought it would add an element of… add to the timbre but I also do… and we’re humming we’re not singing cause that’s also just kind of vibration, you know, that mirrors the strings. But I'm not sure what your question was now that we’ve figured out what we were talking about, what’s the actual question?

KP: Yeah I guess were you just trying to add another color or…

JP: There’s two things. I'm trying to add another color but I'm also interested in how we use our bodies when we play instruments, so like body practice. My two big practices are music and body work basically, so I wanted to incorporate the two. I also think that they’re very similar. And just breathing when you’re playing. I breathe when I play. I feel like a lot of time playing an instrument is just being a dancer, you know, so I was thinking about the body, how we can use the body, and that is a way to use the body that also added a timbral texture but also like a harmonic texture.

KP: Yeah and I guess how does that interact with the vibrations under your chin from the viola?

JP: Yeah, right, I don’t know, I'm just trying to make sure I can hum the right pitch [laughs] I think it’s also a way for us just all to be calm. We’re just all calm and then the music feels calm but I'm not really thinking about how it interacts with the viola, I'm more thinking about how the body feels when you're playing the instrument.

KP: Oh OK. And then yeah particularly some promo material around one of the ensemble releases mentioned cymatics and sound therapies but maybe sometimes there’s a disconnect between something that does… I've heard you say that you want things to sound good but maybe sometimes there’s a disconnect between something that sounds good and something that feels good, vibrationally…

JP: I want it to feel good, I want it all… I'm trying to have it be like more of a tactile experience but I'm not gonna do that compromising what I'm trying to make compositionally. That is a priority but ultimately I'm a composer and I'm not gonna sacrifice something sounding good for the sake of like introducing some sort of tactile element, you know what I mean. I’m not gonna make something that sounds shitty but feels good for us to play because that’s just self-indulgent. So it’s like a balance between those.

KP: Yeah. So there’s a concern for the audience?

JP: Cause I want them to be part of it, I also kind of want to create vibrations that feel good for them too, which is when I was studying the waves and stuff yeah. But then I backed off on that cause it gets a little too new agey and weird. Also like I'm not a scientist, I'm not gonna pretend to be a scientist. But I'm very interested in that, in how sound affects our bodies, for sure. And then the deeper I got into it the more I just started to feel inadequate. I was like, I don’t really know. But I do think it's interesting. I’m very interested in the things we can’t see. You can’t see sound vibrations, we can’t see it, but they’re affecting us and I think that there’s a lot more in this world that we can’t see that’s affecting us. I mean it’s no secret that I'm really into astrology. There’s so much energy and force, I mean we get gut instincts, we get feelings, I just think a lot about what’s not visible to the eye and how it affects us and music really kind of falls in line with all of that, you know. So that’s kind of why I was thinking a lot about, well the vibrations are moving the water in your body, like what’s that doing to you, and I just wanted to understand how to manipulate that but I just don't necessarily... I’m kind of working more on instinct than science, that's what I reserve myself to.

KP: Yeah that’s kind of what it has to be. But that makes sense, you know, if the moon is strong enough to pull up a whole ocean day after day then… yeah. So I guess on one level this kind of seems like dumb obvious but I feel like a lot of your music does deal with waveforms. Maybe there’s a bit of the delay stuff in your solo music where it feels like your placing yourself in like a pool of interference and a lot of the repetition, it doesn’t feel like a linear dot dot dot it almost seems more cyclical. A lot of the string ensemble stuff, there’s a lot of phasing relationships, you mentioned there’s a lot of those trills, I get the sensation with a lot of it that I'm kind of Zooming in and out of waves as you shorten and extend tones where I'm kind of feeling like a long undulating wave and then coming out and seeing like a quick little squiggle type of thing. And of course there’s some beating patterns. So I guess is this kind of a conscious thing, like you’ve got the sound wave waves like the beating patterns and stuff and then you’ve got some composed, structural waves, is that like a conscious mimickry there?

JP: You talking about the string ensemble music?

KP: Yeah or maybe even some of the solo stuff when you’re playing with delay.

JP: I mean I just love the way that sounds, you know, I like the way that sounds. I like playing with those sorts of things but I don’t really understand the question, like is it deliberate? I'm literally mixing textures like that with form, yeah. I mean when I wrote these pitches for us I chose pitches that clash to create beating patterns for sure.

KP: So I feel like a lot of music is very comfortable just dwelling in that beating pattern area but you do a lot more, is there something that keeps you from just making like singing bowl music with your viola?

JP: Yeah yeah, absolutely, I like that but I also like melody, I like tonality, that’s not the only thing I'm interested in. So another thing I think about too is like creating music that kind of errs on the side of drone. I want there to be more, I can’t just… that’s just a little bit… as much as I enjoy that, I want there to be more to it than that. I want there to be a form. I'm also happy to incorporate melodic material. That, on its own, just one thing on its own, start to finish, one thing. Cool, a little boring to me. I think I can do a little bit more. I can incorporate it with something else. I can interweave it with something else because I'm interested in more than just that, you know.

KP: Yeah yeah yeah. And I guess you mentioned the different ways that you deal with time, the metered time, the clock time, the cues, I feel like a lot of times… this may be on the more meditative side of music… particularly with wavy music it can create this kind of sensation where your sensation of the time that’s elapsed is wildly different than the actual clock time played and I guess is there something in these different ways that you’re using time that facilitates that or is that more of just an attention-based thing for you?

JP: I like that idea of not realizing how much time has passed. I’m interested in that, not realizing. Or something’s changing and you're not realizing it's changing til it's changed or… and again, what’s the question?

KP: That sensation of the time that’s elapsed is mismatched from the time played, is that more of an attention thing for you or do you think that’s facilitated by the way you make music?

JP: I kind of openly want that, I want someone to get lost and not realize, I want someone to get lost in it. In a way not that’s boring but it's captivating and you're not thinking about… that’s why a lot of the music’s not metered. I remember when I first was working on Lull thinking I want to make time feel like a rubber band. That’s what we’re doing as musicians, we’re manipulating time. So yeah it's interesting you picked up on that. Yeah I kind of want that, what is time, how can we change how it feels. And I do think that sitting in a sound and slightly altering it can kind of facilitate that feeling.

KP: Have you found that you achieve that through similar strategies or…

JP: I think using time-based scores kind of helps with that.

KP: Have you talked to your other ensemble members, do they get kind of similar sensations working with your music?

JP: Yeah I have gotten feedback like that yeah, for sure.

KP: We’ve kind of talked about a few things framing them against a couple poles, either tensions or concepts and the titling of a lot of your ensemble pieces, it’s always like blank and blank. I have a sense that it’s coming from that place but where does that titling come from and why… well I guess you’ve mentioned that the concertos are a third thing… but I guess why for instance does like Lull not follow what the other string ensemble stuff is doing?

JP: Yeah again, having two-word titles, that’s again just giving myself another parameter, like how many of these can you come up with [laughs]

KP: Gotcha [laughs]

JP: I don’t know where that started but I got obsessive with it. And then yeah the concertos are a different project and those have been one word titles. It’s not the same group, you know, it’s a third project. But yeah I think that that will be an identity probably for the string ensemble project, is that all the titles will be two words if I can keep it going. And Lull and Clamor, they’re both one word titles. And actually, Lull and Clamor, the meanings are opposite, you know, like lull is calm and clamor is an uprising and I kind of try to portray that in the music. Lull is meant to be more of a drone and meditative and Clamor is not, Clamor’s meant to kind of ramp it up a little bit. So maybe the concerto pieces will all have one word titles, I don’t know. But yeah that’s why, the two words are just for the string ensemble. And I kind of set all kinds of weird parameters like that with the solo music. I feel like I got into this thing of doing… at least the last two records, having four pieces and having one be totally acoustic, one be totally electric, and two be a combination of the two. I just like form and parameter, I feel like it just gives… so I come up with these rules for myself to work with.

KP: Yeah now that you mentioned it too I feel like a lot of your records are four tracks, like even the concerto stuff, you mentioned two solos sandwiched in between two string ensembles.

JP: I think some of the solo records might be five tracks but the last two might’ve been four I can’t remember. I’ve done four records, I can’t remember, but I definitely feel like the four tracks might’ve been the last two.

KP: Nice. Is that like an astrological thing?

JP: No it doesn’t have anything to do with that. I don’t know, one of the first records I made too was this piece called Quotidian which actually Katie played on which was four. I like the idea of a suite. I also like the idea of thinking as pieces as a collection of poems. They’re not, they’re similar. Like all the pieces on my string ensemble record are similar but they’re different. If you listen to one of those pieces and you listen to Army of Strangers, totally different. It’s similar, it’s same instrumentation, similar kind of writing but they're totally different pieces but they're related so I've kind of always thought of… whenever I make an album I always think of it as like they’re a collection of poems and they’re each kind of saying something different but they’re related to each other. So I always think that the pieces are sort of related in some way. And a suite is kind of traditionally a form of work and I think that that's subconsciously in my head.

KP: Nice. I’m less familiar with your earlier stuff outside of Braxton but I do spend quite a bit of time with the string ensemble and solo stuff.

JP: I feel like this is where I found my voice. I feel like a lot of earlier stuff was me just trying things out. I feel like I found my voice now and this is what’s relevant right now.

KP: Nice. So maybe this is too personal so feel free to shoot it down but in some other interviews you mentioned an injury and do you think that injury is related to finding…

JP: Yeah.

KP: I feel like usually, like physiological things, you kind of have to be broken down to get stronger, you know, whether it’s addiction or working out or anything.

JP: Absolutely, yeah, totally, like everything kind of changed after that. It was like a rehabilitation and just everything changed after that. So after that injury I only did solo music and from there is where I kind of found the voice where I am now. I feel like everything before that was me trying things out. Yep.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling non-standard notation in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. Alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Additional resources around non-standard notation can be found throughout our resource roll.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-standard notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for permissions and purchasing of your scores; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

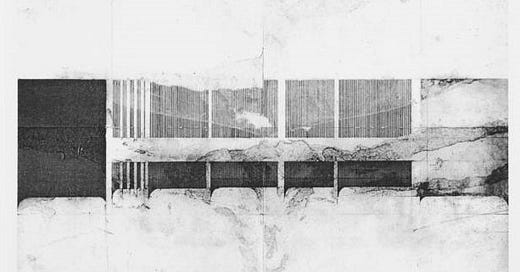

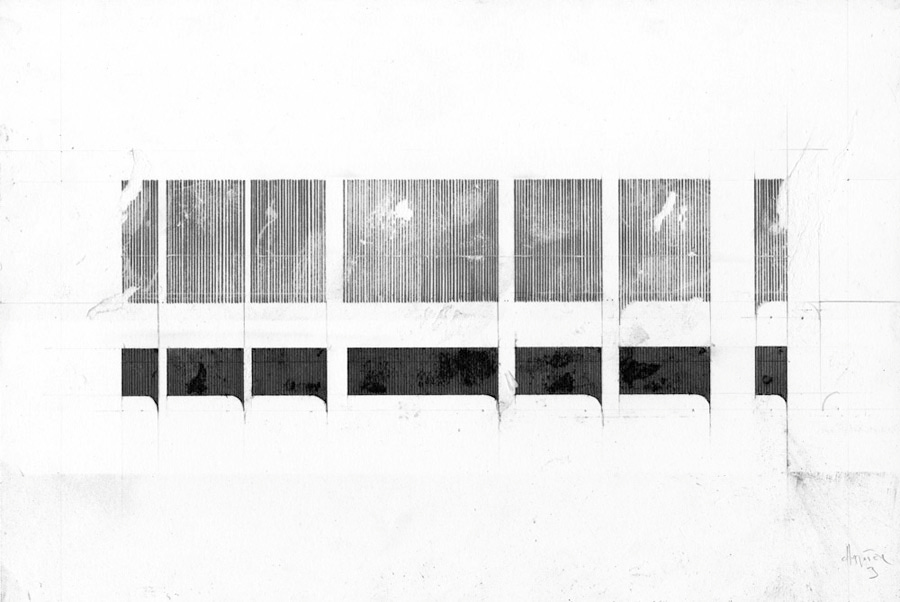

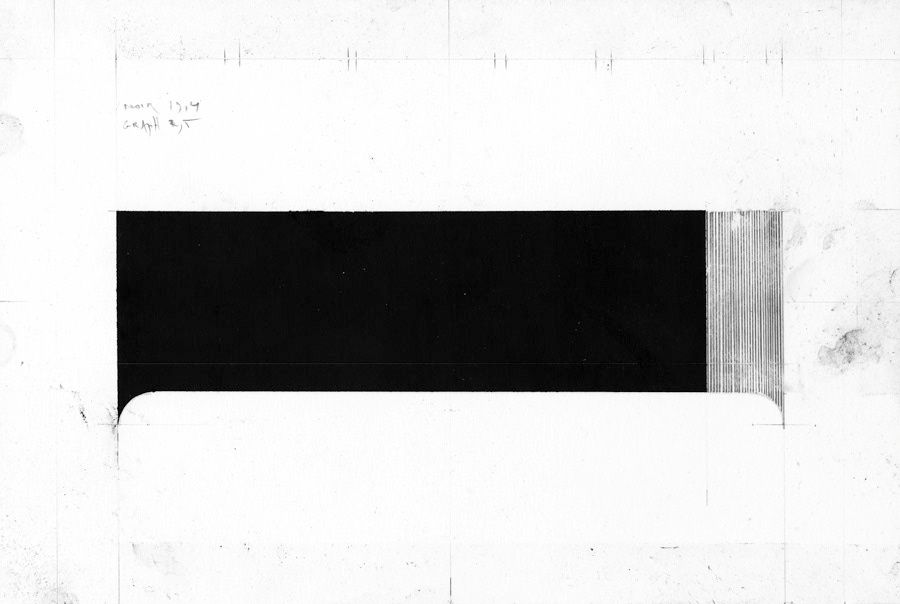

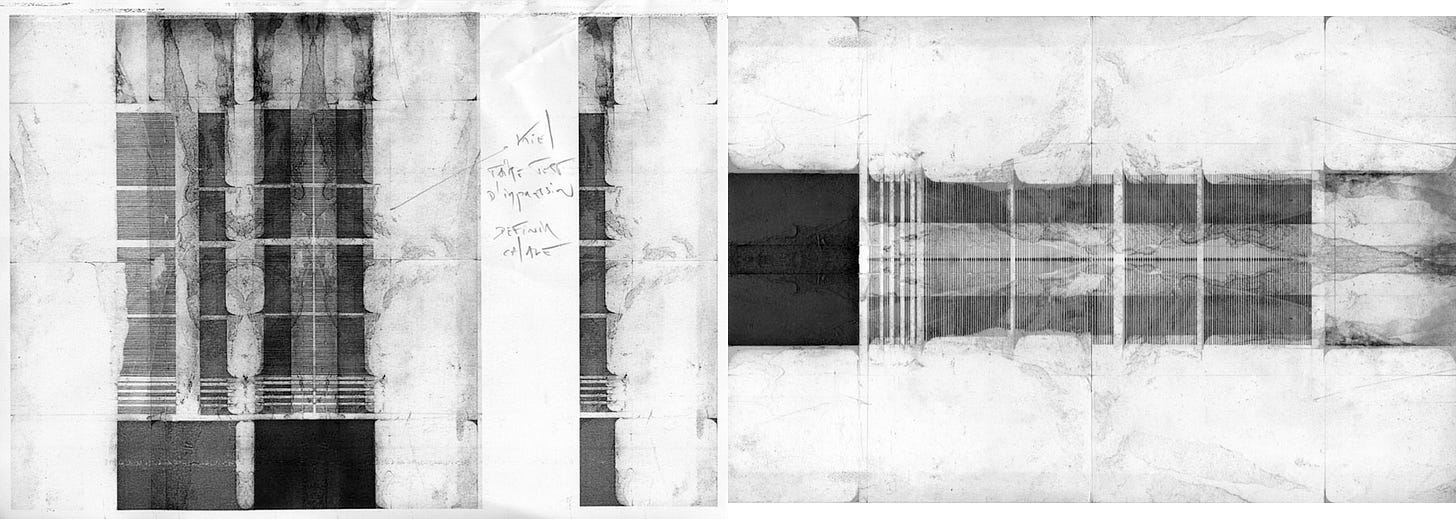

Sylvain Levier & Nebel Lang - Korf ar son (2019-)

Sylvain Levier is a visual artist that currently focuses on drawing to craft compositions that play with visual sound and silence and blur the line between mechanical and manual. His artwork has appeared on the covers of Melaine Dalibert’s Piano Loop and Maelström and Reinier van Houdt and Dante Boon’s realization of Jürg Frey’s l'air, l'instant - deux pianos, with another cover planned for Bruno Duplant’s forthcoming Chance. Korf ar son is Levier’s collaboration with sound artist Nebel Lang, in which the latter provides recordings of improvisations on different pianos in different spaces encountered during his labor as a piano tuner for the former to realize in images. Levier collaborated with Nebel Lang previously in providing the cover for Eskern from Und Ne, another alias. Korf ar son has so far released Wilhelm Schimmel 40445, Wilh. Hauschildt, F. Rösener Berlin 25194, Euterpe 88120, and Doutreligne 2179, each available as prints with a download code.

The original images are a faithful transcription of the sounds, each horizontal axis a minute duration with soundings in white, silence in black, and the resonance and decay in between in grays. They convey no pitch information but rhythm is indicated in spacing, placing, and width of white, curves and uneven verticality might suggest intonation and dynamics, some coarse draftsmanship and relicts of copying lend a sense of texture, and its minimalism seems to offer a cool expressivity. Some early representations more profoundly played at the perceptions or illusions of sound and silence but for their absence of time in relation to the sound so otherwise specific to it they were abandoned. As prints, the subtle variability of their reproducibility inspired a set of studies that present a kind of detail of the original transcription, in different dissections and orientations.

These images are not explicitly scored sound but that they convey musical information seems to ask them to be. In some ways they contain as much or more information as other non-standard scores, even nearly representing the piano keyboard with white notes and in some senses what is between the notes with black. The specificity of piano, tuning, and the place that relates them at the heart of the project and perhaps the impracticality of making minute fragments continuous discourages further realizations; that they are transcriptions and reproduced to share musical information seems to encourage it. The context of a composer associated with visual art making a possible sound art object is just the other side of one associated with sound art making a possible visual art object.

reviews

Antoine Beuger/Anastassis Philippakopoulos - floating by (Erstwhile Records, 2023)

Something about communication without information appeals to me very much. floating by is a duo of voice and breath and plays out like a conversation that’s been distilled and decayed to it’s maximum extent, dwindled to a cryptic echo. It’s a meeting between friends with the words erased, with everything that’s been shared discarded, leaving behind just a hollow silhouette as evidence of the wonderful exchange that had happened there. Like eavesdropping on phantoms, what exists here requires effort and attention to be felt, otherwise it will joyfully dissolve into the air with such weightlessness, opacity and tranquility that it will float by unnoticed.

Anastassis’s voice carries some clear warmth with it. Even without words it exhales humanity. He sings in short phrases that straddle a line between sounding like sentences in a foreign language and sequenced meaningless mouth sounds. These phrases are released in small melodies that feel careful and controlled, demonstrating the understated aestheticism that makes this music so attractive, but also awkward and weak. There’s an audible difficulty in the vocal sliding between deep notes – fully controlling one’s own voice and creating a sonic consistency with it is difficult, and few of us have perfect pitch. I find it comforting to hear human frailty interrupting, but not entirely disrupting, vocal aesthetics in this way.

Meanwhile, Antoine performs using just the sounds of his breath rather than a sung voice. It sounds like a soft, fluctuating gust of air. There’s a surprising amount of timbral variety that he achieves with this technique, but it always sounds like what it is – a man breathing into a microphone, a soft and intimate sound that’s been amplified into audibility. Even more than Anastassis’s performance, it sounds refreshingly natural, but that naturalism is largely ruptured by the aesthetic control that Antoine holds over his own breath – mainly by his pacing and pitches. As much as my gut tells me to perceive the breath as an involuntary sign of life, it’s obvious that Antoine’s performance here is just as voluntary as Anastassis’s was – he’s just stripped his vocal approach down even further.

There’s an element of call-and-response within floating by, like there is whenever two people are talking with each other, but I have a hard time telling whether it’s something really there or something I’ve imagined. Perhaps the ghost of communication is what it is – even with the words removed, the music is still sucked into the everyday concept that two people can share ideas, thoughts and feelings using just their mouths. It makes listening a little difficult, almost disappointing, because I can’t crack the code that will allow me to understand what it is that these two are sharing. I can’t help wondering what it is that they’re trying to say.

But maybe I’m looking at it wrong. Maybe they’re not trying to say anything at all. I can imagine this album as the sounds of two men in a canoe amateurishly singing together as they paddle, as a simple way to kill the time and enjoy each other’s company and nothing more. They aren’t paddling anywhere specific, just deeper into the water, and for no purpose other than to paddle, enjoy each other’s company and sing to themselves. There’s no objective to the song except for singing it, no beginning or end except for when they feel like starting and stopping, guided by nothing except for theirs shared sensibilities – it’s just two voices finding tranquility within a shared aural space as they float by.

- Connor Kurtz

Composition and improvisation were once closely related. Improvisation was a benchmark for testing the theoretic and practical preparation of a musician until the romantic era, where improvisation became somewhat tied to spectacle thanks to composers/interpreters like Liszt, and by late XIX century and early XX it was actively frowned upon by the musical establishment, probably due to these associations with crass showbiz. I have come to believe that improvisation and composition are complementary, and the vast grey area between the two is and always have been ripe for exploration and heuristic development.

While neither Beuger nor Philippakopoulos are known for their improvising skills, their respective practices can be quite illuminating; both are very economical with their material, denying adornment or rhetoric to highlight the material and let it present itself without explanation in order to be perceived as a phenomenon, uncluttered by extraneous reasons or motivations. When they operate at this bare minimum it can be easy to assume that a clear distinction between composition and improvisation should allow the listener to tell one from the other right away, and this may not be quite as clear as it may seem on paper. Another element that renders the distinction between the two even harder is the fact that the album features no actual musical instruments apart from the voice of each composer; Beuger has made use of this many times, including the previous Erst duo with Christian Wolff, but here he chooses to go beyond the tone ambiguity he displays in works like Keinen Fernen Mehr, where he employs whistling as sole medium for the music. The sound produced is far more difficult to relate to pitch structures, being closer to musical breathing than anything else, though the shadow of melody hovers around much of his interventions. Philippakopoulos, on the other hand, avoids improvisation completely, choosing to hum his recent piano pieces, one at a time. My ears were tricked into believing he was somewhat telling us about his composition process, which often takes him out of the studio and into nature, where he hums his melodies and fine tune them until they're ready, by follow fleeting inspiration and somehow composing on the spot, but this turns out to be an illusion: he's simply singing his piano pieces, but the effect is quite startling in a quiet and understated way. Few Erstwhile releases have a cover art that actually represents quite accurately what's going on with the music. The painting depicting two persons on a boat is as accurate as anyone will get to describe the music herein; as I play the album, I can't help but feel that I, the listener, am the body of water on which the boat and the two composers are making the music. The sounds of my listening environment give life to the surface in which the music is happening, and because the sounds made are made by bodies and not by musical instruments as machine extensions of the body the limits of the boat, the artists or the water seem both fragile and sturdy, a beautiful and understated paradox that's present throughout the album. The paradox doesn't end there: this album is both quite radical but also very inviting. I stated that as a listener I felt as I was part of the water. This doesn't mean that I don't feel like I'm in the boat with them, as quiet observer. At some point I discover they are, in their non verbal way, also talking about me.

- Gil Sansón

Alan Courtis and Ben Owen - Environmental Conditions (Park 70, 2023)

Alan Courtis and Ben Owen present six tracks utilizing contact mics, electronics, mixer, speaker, and duplex machine on the 31’ Environmental Conditions.

Each track features similar rhythms and though their textures are distinct the indefatigable rattle seems to convey they share a source in the duplex cleaning machine. Some textures sound more water shower or jingle bells or lotto machine than cleaning machine. Some center the low bands of hearing and some the squealing. The extended tracks sandwiching the others insert cuts of silence, voices, electric pulses, radio, and other incidental and supplemental sounds. To take the title at its face a change in the rhythmic texture would indicate a change in environmental conditions but these other sounds that both sometimes provide a sense of stable place and appear less changing or manipulated seem to question what’s really changing. Maybe it’s the material the machine is on or the location and direction of it in a room. Maybe it’s those same parameters but for the recording equipment. Either way it draws the ear to wonder on the role of space and place in experience and the narration of recording and recording equipment.

- Keith Prosk

Sergio Merce - Traslasierra (expanded landscape) (Hitorri, 2023)

Sergio Merce realizes the eponymous piece for ewi, virtual instruments mediated via ewi, field recordings, and synthesizer on the 27’ Traslasierra (expanded landscape).

Overlapping layers of waves of various periodicities and frequencies. The sine tone whine and low turning motor could be confused for microtonal saxophone and orchestral swells of winds and strings disguise their virtual sources. Sounds like birdsong, cicada chittering, and flowing water feel real but something nebulously strange in their timbral character or the ease with which they extend into synthetic sounds casts doubt on their source. Textural surfaces recur but continuously expand to unravel like a wave from a circle. Long rests as weighty as the sounds themselves, the tinnitus of digital silence alongside teeming environmental stillness. Through mimickry and collage it plays at the interfaces of electric and acoustic, digital and physical, fantasy and real, repetition and progression, sound and silence for a kind of transcendental dream space.

- Keith Prosk

Quatuor Bozzini / Konus Quartett - Jürg Frey: Continuité, fragilité, résonance (elsewhere, 2023)

Isabelle Bozzini, Stéphanie Bozzini, Alissa Cheung, and Clemens Merkel and Christian Kobi, Fabio Oehrli, Stefan Rolli, and Jonas Tschanz perform the Jürg Frey composition for string and saxophone quartets on the 51’ Continuité, fragilité, résonance.

Clear thematic segments transition from one to the next seamlessly. Voices enter staggered and drift to sound all together, flowing and ebbing between a melodic propulsion and harmonic gyre. Beats of discrete tones root sustained ones, beating, and this recurring pairing lends a sense of circularity to sounds’ unfolding. Sound and silence sometimes reverse roles and the former assumes the stasis and depth of the latter with sustain. Even the two disparate quartet textures can blur like the cover watercolor could play at the simultaneous bucketing of yellow and green and their contiguous relationship on the visible spectrum. Always a dynamic equilibrium between two limits and at their tipping and intertonguing generate moments of stirring emotivity.

- Keith Prosk

Germaine Sijstermans / Koen Nutters / Reinier van Houdt - Circles, Reeds, and Memories (elsewhere, 2023)

Germaine Sijstermans, Koen Nutters, and Reinier van Houdt perform a sidelong composition from each with clarinets, electric organ, harmonium, voice, objects, sine tones, recordings, and tape on the 60’ Circles, Reeds, and Memories.

In its odd harmonics the clarinet can assume a texture similar to synthesizer that in turn blends with the respiration of harmonium and beyond these three blurring sonically the compositions of mostly sustained tones of comparable pacing could blur the works too. But “Linden” has many moments of blooming melodies and maybe its textures recall the material in its title, the nasal expansion of harmonium like the crack and creak of wood, something akin to stick clicks along a fence from objects, and pops, thresholds of vibrational excitation in breath tones, and chirping that draw attention to the reed. The long soundings of “A Piece with Memories” overlay in such a way to disorient my listening memory and though spoken word would tether moments to a clearer sequence its sparsity, my ignorance of its meaning, and its seemingly intentional obfuscation in barely audible volumes only teases a trail. And “Harmonic Circles” seems sisyphean cycles of beats and beating tones snowballing and bursting into swells of deep harmonies. Distinctive effects from shades.

- Keith Prosk

Taku Sugimoto - Manfred Werder: ein(e) ausführende(r), seiten 977 bis 982 (self-released, 2023)

Taku Sugimoto performs six pages from Manfred Werder’s ein(e) ausführende(r) with guitar on this 47’ recording.

Footsteps, birdsong, auto traffic, and the rest occur in plazas, parks, underpasses, and other places. I say these things like all feet fall the same, all birds sing the same song, or the coughing jalopy is close enough to the whisper of an electric engine. Every sound is as divisible as not and the unique entourage of others in the moment that color them only accentuates the singularity of them even from the same source. The presentation of video alongside the blind recording emphasizes this essence of place and time at the heart of it. The choice of performer sounds, that themselves could be said to be as much the same in the same way as the others and that balance sound and silence, asks what they share with these other sounds, what sound shares with silence. And like a chick’s chirp is not a mature call or a child’s run is not a caned creep even coming from the same thing sounds can share less with themselves than they do with the rest in the moments they occur. That silence is as close to sound as sound and vice versa.

- Keith Prosk

For additional words around the piece and a realization of other pages, see Yuko Zama’s Silence, Environment, Performer from surround, issue 1.

Nate Wooley - Christian Wolff: For Trumpet Player (Tisser Tissu Editions, 2023)

Nate Wooley performs a Christian Wolff composition for solo trumpet player on the 22’ For Trumpet Player.

As with all Tisser Tissu Editions releases, For Trumpet Player presents the sound alongside direct and indirect context, in this case a conversation between performer and composer, a linguistic translation of the score, and an essay on aspects of interpreting the music from the performer, the first and last with details of the notation.

Indeterminate rhythm and intonation lends a sense of cadence akin to stream-of-consciousness, the perception of the continuity of the melody shifting with shifting speed and duration of sounding, illuminating the player in choice and also in breath and buzzing and spitting - with distinct moments of somber textures and muted colors that could be more player choice, or referential material, or sectional material - like text on the page assumes nuanced meanings through the reader’s speaking, that can make repeating phrases hit different with a transposition in intonation. As the context guides towards, it appears clear the piece makes playing as special as speaking, and that it would change as the player changes with the temperament of the time.

- Keith Prosk

Thank you so much for sharing time with harmonic series.

$5 Suggested Donation | If you appreciate our efforts, please consider a one-time or recurring donation. Your contributions support not only the writers but the musicians that make it possible. For all monthly income received, harmonic series retains 20% for operating costs, equally distributes 40% to the participating writing team, and distributes 40% to contributing musicmakers (of this, 40% to interviewee or guest essayist, 30% to rotating feature contributor, and 30% equally to those that apprised us of their project that we reviewed). harmonic series was able to offer musicians and other contributors $4.42 to $5.89 for March and $1.95 to $5.19 for April. Disclaimer: harmonic series LLC is not a non-profit organization, as such donations are not tax-deductible.