Houston, Texas’ Nameless Sound performance series continues celebrating its 20th anniversary by diving into archives of previously unreleased sound, video, and stories from musicians with deep connections to the series, most recently featuring Pauline Oliveros. Previous profiles include Joe McPhee, Maggie Nichols, and Alvin Fielder.

Eric Wong recently completed the Multiple Portables project, a series of five multi-channel tracks that intends the listener(s) to play each channel through a different portable device. I think this invites an intriguing listening experience with limitless variability by encouraging the use of devices with different fidelities (often dismissed as “bad”) to explore the behaviors of relatively fixed sounds in different spaces and in different locations within those spaces with others. So much of my listening to recordings is through headphones, stationary, and by myself; this project reinvigorates the experience.

Violist Frantz Loriot recently started an interesting interview-based project, Recordedness, to provide perspectives around sound documentation and the act of recording. Published interviewers and interviewees include Sean Ali, Carlo Costa, Nomi Epstein, Flin van Hemmen, Yan Jun, Annie P. Lewandowski, Loriot, Joe Moffett, Tom Soloveitzik, Deborah Walker, and Theresa Wong, with more to be published. Loriot also released While Whirling for solo viola this month.

Contrabassist Daniel Barbiero - an advocate for the kind of alternative notation presented in this newsletter - recently published an interesting essay, Graphic Scores & Musical Post-Literacy, on Arteidolia that provides musings on the implications around interpreting graphic scores with a brief historical overview. I’m particularly intrigued by the suggestion that the appeal of graphic interpretation might correlate with an environment in which music is more often approached through recordings than scores. And, though not explicitly stated, that graphic scores might provide a means of equilibrating the power balance between composer and performer.

conversations

I interview Nate Cross, who runs the Austin, Texas-based labels Astral Spirits and Astral Editions and currently plays in USA/Mexico. Over video chat, we talk about some aspects of starting and running a label, the impact of Bandcamp, the co-operative Catalytic Soundstream, labels as communities, advocacy, and recreating that special record store feel in the digital age.

Just this past month, Astral Spirits has released: Aaron Novik’s Grounded; Mats Gustafsson & Joachim Nordwall’s Shadows of Tomorrow; Chris Schlarb & Chad Taylor’s Time No Changes; Michael Foster & Ben Bennett’s Contractions; Chris Williams & Patrick Shiroishi’s San Soleil; Vernacular’s The Little Bird; and Stefano Leonardi & Antonio Bertoni’s Viandes. Astral Editions released Amirtha Kidambi & Matteo Liberatore’s Neutral Love and Gryphon Rue & Merche Blasco’s North of the Future, and announced Powers/Rolin Duo’s Strange Fortune.

Keith Prosk: Hey! How are you?

Nate Cross: Good! How you doin?

KP: Good good. You can hear me alright?

NC: You’re just fine, yeah.

KP: Well, thank you so much for hopping on and spending some time with me.

NC: Of course! Sorry about last week. Was it last week? I don’t remember what week it was.

KP: Yeah, I think a couple weeks ago. But things have been busy for you?

NC: Yeah, this time of year, with my day job, it’s sort of like December, November through March is crazy. And then, I try to take a break after that. I work for the SXSW music festival.

KP: They just had a week-long online thing this year, right?

NC: Yeah, it was weird.

KP: What was your job like this year with all the shake up?

NC: So normally I’m in the production department, which is like live events, and this year, obviously, I was freaking out. I was like, “Am I going to have a job? What do I do?” And they ended up splitting our department up into different places and I couldn’t figure out… I kept being like “I don’t know what to do.” So I did this COVID compliance officer training and was a COVID compliance officer for our office, ‘cause I knew we’d need that. And then all the sudden, I ended up getting on our video team and helping to schedule everything. And then all the sudden I had like four jobs. And was doing too much. Which was a good feeling, to actually be needed. Yeah, it was strange. It was a lot of work leading up to it and then when it happened, it just... happened. And that was it. [laughs] There were no major hiccups and it was fine.

KP: So you kind of do stuff throughout the year and you’re mostly running the label at night, right?

NC: Yeah, so I’m a full-time year-round employee for SXSW now. And it gives me some flexibility. Like I still have to work during the day, yes, but it’s a little… from May through July, August there’s not as much to do. So I have a little bit more flexibility where I can kind of multi-task and knock out the spreadsheety and really basic stuff. But in general at night time is… this is when I do my label business for the next few hours.

KP: I actually wanted to get into that. So in the first interview for this newsletter, I asked PG, who I think of as a successful organizer, what the nuts and bolts of organizing were, and I similarly wanted to start out, just right off the bat, with you, asking about some of the nuts and bolts of starting or running a label to maybe provide some sort of fun how-to for enthusiastic people who are otherwise intimidated. So, right off the bat, wide open, any salient points or advice that you would drive home to people?

NC: ...

KP: I have some more narrowed-down things, if you wanna start with that…

NC: [laughs] Yeah, let’s start there. I’m like, “What is the takeaway?” I don’t know.

KP: Yeah, so I feel like I have a good sense of, or some visibility on, the promotion part of a label. And I can imagine the coordination between musicians and engineers, pressing plants, all that. But, I guess, how do you even receive recordings? I imagine at this point you’re receiving submissions, which you curate. But starting out, did you reach out to people, commission recordings, what does that part of the process look like?

NC: Yeah, the way I sort of started out and I think is a good… it worked well for me and I would stress, I think, the time in our days, right? Like labels are different. It’s not like the days of old when labels were like a team and everyone had their role… I mean there are still teams, but people were making money off of records back in the day. Whereas now, it’s very DIY, you’re getting by. A really successful record is one that makes money back, and you might make a little beyond that. So, it’s kind of like learning to do things as cheaply and bare-bones as possible. So when I started, I wasn’t in a place where I could actually reach out and be like, “I’m gonna pay for you to go into the studio and do this.” It was more… like the first one that happened, the Icepick tape, Hexane, the very first one, I knew Ingebrigt from here in Austin and he had mentioned that he did a recording, or a couple shows in New York with Nate Wooley and Chris Corsano and I was like, “That’d be incredible.” And I hear it and they’re like, “Oh, yeah, the quality is really bad, it’s not good, and you can hear people, their glasses clinking the whole time and everything.” And with my background I kind of loved the idea of that. So I started off sort of going after things that I didn’t think… because I was doing tapes too and I was like, “It doesn’t have to be perfect,” or it doesn’t have to be this monumental, life-changing… all the hyperbole, it didn’t need to be that. So I sort of just blindly emailed people that I didn’t know and just asked if they had recordings that they wanted to put out, like I’m trying to make a few…

KP: Yeah, I remember [local Austin groups] SSBT and Shit & Shine from the early days…

NC: So, Shit & Shine… I know Craig obviously, I've known Craig for awhile, from playing in bands, and… currently in USA/Mexico, but I’ve known Craig for awhile. That was when we were still… I was still playing with him here and there. We had this Tuesday jazz chat series, it was this thing we were doing where we’d just be in a shed and pretend like we could play music. But it was great and it was a lot of fun and I was like, “This is a perfect thing to release.” And SSBT, yeah, that was Chris Cogburn, I knew him. So it was sort of… I think that would be the takeaway, the advice is start from your circle, start with the people you know and then they’re gonna slowly… like through Ingebrigt and PG I met a ton of folks and that’s how I met Dave Rempis and Fred Lonberg-Holm and the Ballister recording that I released that first year was me sitting in the front row of the concert at the North Door in Austin with a zoom recorder. And that’s where the recording of that came from [laughs]. So I was trying to be as resourceful as I could. And from there, I have a friend who has a studio kind of in our neighborhood, it’s like a little backhouse, and so I’ve used that a handful of times. Icepick, that’s where they recorded the LP, Amaranth. And Susan Alcorn, Joe McPhee, Ken Vandermark, when we had them here in Austin, I had them record there. And same thing, it’s not a thousand dollar studio, you know, it’s my friend’s backhouse, and it sounds great. One of the funniest things was, when Icepick recorded there, Nate Wooley, I think he had just gotten done recording something at like The Record Plant, or somewhere insane in New York, had all these fancy microphones, and then he comes here and Ian just put a SM-58 right on his trumpet [laughs]. And then we listened back and he was like, “Sounds just as good” [laughs]. But yeah, that would be my start, from there. Resourcefulness is a good skill to have in the beginning.

KP: Yeah, so you mentioned keeping the cost low, but Astral Spirits has had a pretty distinct, unified image from the get go. So, I mean between kind of… not necessarily costs associated with recording, but kind of design, art, sometimes you throw in liners, what are some of the expectations for those costs in the early days and maybe for a recording that you’re putting out today.

NC: Yeah, so, that was one thing I kind of took on before I started the label. I had my friend, Mason McFee, who did all the design. So I went to him and kind of made a deal with him and paid him to go ahead and do the… he did all the logo and the templates for the original tapes. And pretty much, the template’s more or less the same. The art work’s changed now. I sat with him for awhile and went through a bunch of iterations until we got that down. So the design, that was probably the thing I had in place almost before anything else. I just kind of had this idea that it’s hard to be recognizable, I guess, in a way. And I just thought it would be a cool thing. Especially in the improv world, harkening back to Impulse! and that sort of stuff, I just don’t feel like that was around as much. That was really important to me, to get a really good aesthetic to it. Initially that was the idea, was to do tapes and make it more palatable to people who wouldn’t normally buy improvised music. But as far as costs, at first it was just getting the tapes out. And then they started making some money. And so I eventually built up to where I was able to do the Icepick LP and the Joe McPhee LP. And you know liner notes, a lot of it was just kind of, again, having friends. So Mason, he gave me a good deal on the artwork and after I paid him for the design and the whole build of it, we came to an agreement on what I would pay per tape, ‘cause he was only coming up with the symbols and changing the words and not doing art for each one. This is a way he knows I’m gonna do this many tapes, he’s gonna get this much money. But it’s cheaper for me because I’m not paying what I would pay a bigger name artist. With the liner notes, I knew Clifford Allen from when he lived here in Austin, before he moved to New York, so I hit him up and same thing. He gave me a friend rate, a little better than what he would charge. ‘Cause it was, again, a tape, so you can’t fit as many words in a tape as well. So yeah it was the same idea of trying to spend little bits here and there to make it more interesting and then build upon that. At this point now I’m willing to spend more because I have more resources. Yeah, I don’t know, did I go somewhere weird with that?

KP: Yeah, no, that’s good. I think you mentioned pretty much, and this is what I imagined too, is that the best case scenario for a physical release in this kind of music is really just breaking even. In the early days, were you breaking even less? Are you doing pretty well now?

NC: In the early days I got really lucky cause I was under Monofonus Press and Morgan and that whole crew. Morgan is the reason I have a label. He was willing to help fund me a little bit and get up off the ground. It wasn’t funding like funding a start up company but, you know. It’s helping with a couple tapes a month, so like $700 or something. So anytime something didn’t… if there were failures or little drops, he was willing to cover that and help me get through. And it took a couple years but I was mostly kind of treading water for awhile, enough to like, “OK that batch of tapes did what it did, I made enough that I now have a nest egg to do another batch of tapes.” And so we built from there. And Morgan helped me get the first LPs out. And then it just kind of built from there. There were a few that didn’t… as expected, there’s always gonna be a few that you just never know. But at this point, yeah, I feel very lucky and I’m very… not anxious all the time, but there’s a part of me that’s always anxious of like when’s this gonna… when am I gonna make a big mistake here. Not that I don’t trust myself and the music I’m putting out. But it has been going well.

KP: I might be in the right bubble or something, but I feel like Astral Spirits is like the label. I feel like I see Astral Spirits more than like Intakt and Not Two and Trost....

NC: Well, that’s kind of my own doing. I mean this was my goal initially too, in starting out, which, this is another thing… I don’t know if this is good advice or not, but it worked for me… I really did want to hit the ground and just go. When I started I wanted to put out non-stop, put out stuff, put out stuff, put out stuff, in order to get that name recognition. And for better or worse I keep telling myself that I’m gonna slow down. “This is going to be the year I’m only gonna do so many releases.” I just do too much. And it’s because I just get excited. People send me stuff and I get really excited about it. “Well, I have to do this record for these people.” Or “I’ve always wanted to work with this person.” So that’s probably why you see my name more, [laughs] because I’m always releasing stuff. And that was intentional at first, but I don’t want to burn people out also, that’s my worry.

KP: No, I feel like it fits with the nature of the music, like you have a few thousand good to great improvising musicians putting out more than a handful of releases a year. There’s a big pool of great material to choose from.

NC: There’s so many. I think that’s kind of where I’ve started, why I’ve kept doing so much. I feel like with press a lot of times… you see a lot of the same records get all the accolades… it’s the same ten names. And meanwhile I just keep getting more and more submissions from people that I know and don’t know and I’m just blown away. I’m just like, why? I try to even the playing field, is what I hope to do. I want to put Chris Williams and Patrick Shiroishi, who have a new tape coming out, like I wanna put them next to Roscoe Mitchell and people like that. ‘Cause I think everybody deserves to be on an even playing field because there’s so many amazing folks out there. I think it’s worth doing, to get rid of the hierarchical part of it.

KP: Yeah, I think, I don’t know if they’re considered like forgotten tapes on Astral Spirits or not, but you introduced me to Andrew Smiley and [Teddy] Rankin-Parker, who are a couple musicians that have really stayed on my mind since their Astral Spirits releases, or since I heard them.

NC: Yeah, Andrew’s amazing. He just put out another solo record that’s just as incredible.

KP: mmhmm So you started as a tape label, and you were exclusively a tape label for a little bit, I’m imaging that’s because of cost but also - I think I’ve read in other interviews from you - to reach a younger audience as well for this music. But now you’re incorporating CDs and LPs. So what’s the decision making process between what goes on what format and how many copies you put out?

NC: It always depends per release. At first the LPs... I wanted it to be… because they’re so cost-prohibitive, right, like you’re coming from this world where... a tape, like it’s $500, $600. If it goes wrong one time or two times, you’re not gonna lose a ton of money. You’ll survive. At first when I started doing LPs, it has to be something I know will sell. So it was Joe McPhee and Icepick and Thurston Moore and things like that. And then as I’m going I’m trying to do more like… what would be a good example… like Charles Rumback maybe isn’t a huge household name but that piano trio record was mindblowing. And Quinn Kirchner, that was one, we went back and forth for awhile actually. ‘Cause he sent it to me, The Other Side of Time, and I thought it was great, but I was like, “Oh, it’s a lot of material. We can do a tape but I can’t do an LP. It’s a double LP, I can’t afford to do that.” He kept pushing back and pushing back and eventually we went for it and I was so scared. Because it’s a double LP, and then... gatefold and this beautiful thing and it just sold like crazy. So I can never tell. But I don’t know, I think these days, I don’t ever want to get rid of the tape side of things, because it is how I started. And I’ve tried really hard to not make it… so when I do press I make sure I’m doing them equally and pushing the same. Like I don’t want… there’s always a tendency to think of the cassette or the tape as a lesser release, right. Like a lot of reviewers will do that. And people in general. But I try to not do that. As far as what I decide, a lot of times it’s just talking with the artist and seeing what they want. And I do have to, in my brain, try to think like, “Is this gonna sell?” Which I hate, that it comes down to that in a way because I like all the music. Like if I could put everything out on vinyl, I probably would. And then the CDs and stuff like that I just do… I’ve never been a CD person personally. They sell fine. I don’t sell that many. But I just got enough emails from jazz folks that were upset that I wasn’t releasing CDs.

KP: Right, so I’ve super noticed that too, to where I’ve seen some of the older jazz reviewers knock something for being a digital-only release, and even in their bios, they’ll put that they really love CDs [laughs]. Do you have some of your own associations with each of the formats and kind of like a picture of what each format listener is.

NC: Yeah, yeah. I think… they’re all great. They should all have their own place. And that’s kind of why I’ve tried to keep doing them all. Like I don’t ever want to stop doing tapes, or records, or CDs, or digital, because it’s all fine. I think I saw a comment the other day or something on the internet where there was an album that was only on LP and digital I think, and someone was like, “Well, I don’t do digital and I won’t do vinyl, so” and I was like…

KP: “At that point what do you do...”

NC: Yeah. Are you only gonna listen to music that’s only on CD? It’s strange. It’s a strange way to decide what you’re gonna listen to. Format wars are a weird thing to me.

KP: The last thing that I’ve got along the nuts and bolts piece is… what does it mean to produce or executive-produce something?

NC: [laughs] great question, actually. I would say usually that would go along the lines of who’s helping run it through the course of production. So like a good example is the Ahmed record that just came out. So Seymour and I are both credited on there and it’s because, from the group, Seymour was the one I was talking to that helped do some of the mock ups for art and was talking to my art guy to get everything buttoned up and set up. And he was the one who helped organize with CTS images to get the photos of Ahmed Abdul-Malik that we could use and he like worked it out... They just let us use them, which was very nice of them, we didn’t have to pay for it. So that’s kind of what I would say is producing. It’s not the like… money is part of it but it’s mostly I would say moving it from “let’s make a record, here’s this music I have,” taking it from that and then going through all the stages of art, mastering, shipping it off to the pressing plant, getting the press release out, it’s just doing all those things. I don’t put that on every record because it’s just, like, running a label is kind of being a producer. It’s sort of glorified. I’d say running a label is more like being an assistant more than anything [laughs]. You’re more of an administrator really, in general, which is fine.

KP: Nice, yeah, for some reason I always thought it had to do with something in the studio...

NC: There is that. You can say, produced by… usually that’s broken down now as in like engineer, and then mixed by, mastered by. Like produced would also be if someone was... I guess you could say, with the example of Alcorn/McPhee/Vandermark, you could say I produced that because I was in the studio with them while recording. I didn’t tell them what to do but if I would’ve been like, “Ken, I think you should play clarinet on this next piece” and blah blah like that would be considered producing too. But usually on the records I’ve done with Ahmed and Kuzu and others where there’s a producer credit, it’s more of that other stuff.

KP: I kind of want to talk about Bandcamp a little bit. I’ve noticed since Bandcamp Friday started that I probably get a few hundred emails [laughs] in the couple days leading up to it. It feels like everything is really frontloaded every Bandcamp Friday and then it just kind of dies off the rest of the month. I feel like one other thing I’m kind of seeing more as well is presales. So I know Astral Spirits is doing this as well, to where an album will be announced… this year, there were some things announced like six months in advance... I’ve seen things announced a few weeks to a few months in advance. Which I imagine is to kind of get a little income flowing right off the bat and smooth out those spikes around a release. But I just wanted to ask for your general perspective on Bandcamp and how that influences your model as a label as well as any benefits that you see beyond the obvious increase on Bandcamp Fridays and also your frustrations too.

NC: Yeah, I think, obviously it’s done very well for them and a lot of folks, including myself. I think what I’ve tried to do with it is use the preorder side of it more because I think part of what is hard… it’s sort of frustrating is what you said where it’s like all this fervor leading up to it and then it hits and there’s this day, weekend - it kind of lasts over the weekend, there’s like a spike and then goes down a little over the weekend - and then it dies off. I’ve found that the preorder model has worked better, both in terms of getting money ahead so that you’re evening out everything and because it gives it a longer life, or a couple bumps. Like in the previous model, the release date would always be the big day. Even if you did a preorder for it, if it wasn’t attached to Bandcamp Friday, it would be fine and there would be a little bit, but it wouldn’t be the same outcome as the Bandcamp Fridays have given. So the nice thing is you get that preorder bump and then you wait a couple months and it actually comes out. And I have seen the six month, or the really long preorders, and those are a bit much, because you kind of forget the record’s even there [laughs] but, I mean, it’s been great. But I can understand a lot of people’s frustrations. It’s definitely changed the way a lot of smaller labels have run their business. It’s sort of like a slightly better version of Record Store Day, in a way. It’s just gotten so, like you said, you get a hundred… between the emails from everybody and the messages, I mean, it’s hundreds and hundreds of emails. So everyone is taking advantage and it’s just getting to be almost too much. Some things just get lost in it, because there’s so many releases, that’s what’s hard, I think. And a frustration is you can put something up and then all the sudden you’re like, “Well, why didn’t anyone hear about it?” And it just got lost in this chain of emails, right. So, I don’t know, it’s complicated. I think there are a lot of people that want to get mad about it because it has changed the way labels are functioning. I don’t know, I’m very curious to see what happens after next month when the last one hits. I’m assuming next month... they’re saying next month is the last one, so I’m curious to see how that comes out in the end. I don’t know. That’s a tough one. It’s obviously benefitted me in a lot of ways. And Bandcamp, I would say Bandcamp has benefited me in a lot of ways and a lot of small labels tremendously. I don't know if my label would be as successful as it is without Bandcamp honestly. The way it’s set up and the user-friendliness, it’s just a great site. And I think they’ve done a really great job with the writers and the actual content they produce, like the daily, I mean I discover a lot of stuff that I like on there that I didn’t know about.

KP: Yeah, they kind of got that whole vertical thing going on. Are there any concerns about… I know there’s Soundcloud, which a lot of musicians still use to put out independent music, but are there any concerns about how dominant Bandcamp is? I know the decision making has been relatively good so far but…

NC: Yeah, I’ve felt OK about it just from my small interactions with Andrew Jervis and some of the folks that are the main people there, the editors and whatnot. For the people that wanna say that Bandcamp is getting too big, I understand it’s for profit, there’s always an inherently weird, not sinister, but there’s always a weird quality when it’s for profit. I mean, my label’s for profit. There’s always something a little off about that. But I think in the grand scheme of things when you look at Bandcamp and their model and what it actually pays to people versus… I mean Bandcamp compared to Spotify, I don’t know the numbers, but I would say it’s still a very very big gap between the two. There are a lot of things you can criticize about them and rightly so, but I do think they have really helped a lot of smaller folks get attention that they wouldn’t get otherwise. Even in the world where we don’t have major labels any more, per se. Major labels are like the Spotifys of the world where you can’t even compete with them, they’re just in a different world. There was the phase of the indies vs the major labels, right, that was like the big ‘90s move. And that shifted. The major labels kept going stratospherically and they’re the Beyonces and it is what it is, but the indie labels now I feel like have kind of just jumped. Indie labels aren’t even indie labels when I think of like Sub Pop and Secretly Canadian, some of them… good for them, I have no ill will toward any of them… I would not consider them small, independent labels. They have teams and offices in multiple cities, even Thrill Jockey. So I think Bandcamp has helped bring another level of actual smaller folks like myself and International Anthem that aren’t like these giant conglomerate, not conglomerate, but I think you understand what I’m saying… levels the playing field a little bit.

KP: Yeah, it’s use as a DIY tool to get your sound out there cannot be overstated. It allows literally anyone to release music to the world and get an audience for that music...

NC: I like to try to think of it like a digital modern version of a record store in a way, ‘cause there are the recommendations, and any algorithm is gonna be weird, but this is the world we live in now. But it feels like that, where you can search around on Bandcamp and search in tags and find stuff that you don’t know anything about and you’re like, “Well, this is great” and now this person knows about it. There’s something kind of cool about that, in that way of like when you used to go to the record store and they’d show you, “Have you heard this!?” and you’d be like, “No.” That part of it hits my nostalgia.

KP: Yeah, I find a lot of times I’m trying stuff out just ‘cause I like the cover, which is exactly what you do in a record store, right.

NC: Exactly, yeah, I think that’s cool, I think that’s great.

KP: Since you mentioned Spotify… you recently became a partner of the Catalytic Soundstream, which uses Soundcloud as its base for the sound files, but going back to that Bandcamp thing too, I love that you can see which musician or which label curated the releases on the stream. But I guess I wanted to ask, beyond just allowing your music to be streamed, what involvement do you have with the Catalytic Soundstream?

NC: So I help get the label tier... I sort of help organize that and make sure that every month there’s a new batch of records from each label. Right now it’s four core labels, it’s Astral Spirits, Relative Pitch, Corbett vs. Dempsey, and NoBusiness. And so I help coordinate them and get… I email them and say, “Hey, send me your five albums for the month,” and they send it and I help upload it to Soundcloud and get the metadata in place so it can go live each month. And I kind of, I don’t know, I don’t remember exactly when I heard about this, but it was around the beginning of the pandemic about a year ago, not quite a year ago when they were gonna do the Catalytic Sound Festival in Chicago and I was gonna go talk at the festival. I still did in the virtual version but... I started talking to Ken and Sam Clapp a bit more about it and I kind of had a few different ideas I wanted to run by them, because I knew they were doing this soundstream idea, it was to do a label tier and just get some labels that weren’t members of the co-op per se but have it be labels that were sort of related. I’ve done records for so many people that are part of Catalytic… Relative Pitch, NoBusiness, it seems like it was all kind of related in that same way of like having a digital record store. Like, “Hey, you like Luke Stewart, check out this other stuff from Astral Spirits” or “You like Mats Gustafsson, check out NoBusiness, they have a ton of other stuff.” So I brought this idea of trying to add another tier to what they were already planning on doing, which was in a beta testing mode. And they liked it a lot, so we kind of rolled with it. It wasn’t too much work, I think for them. The majority of their work was building it out, which was insane, so Soundcloud I think for them was the easiest way to do it without building something from scratch. But yeah mostly I just work with Sam every month to administrate the label tier. And it’s great. I just thought it was a great idea and I love what they’re doing. I love the co-op aspect of it and that everyone’s getting paid the same amount. And the labels, the albums that are up… you know, it’s not much money coming in because it’s based on the amount of Patreon subscribers. But, still, being able to give someone $10 versus $0.10 from Spotify is better.

KP: Yeah, I think that’s exactly what I heard, that the first week it rolled out, and I imagine it’s only gone up, they were able to hand out $10 checks versus you would get tenths of a cent from Spotify for most of these musicians.

NC: Yeah, I just thought it was a great idea. I loved it. I do think Spotify and streaming is pretty evil in general. My wife has a Spotify account; I do not have a Spotify account. To be fair, I do have some Astral Spirits albums that are on Spotify because... as a general rule I don’t, but I also am not willing to be that gatekeeper for the artist. I’m not going to say, “No you cannot do this, I will not put your record on Spotify,” because I have the ability to. If they really want it up there, I will do that for them. My job is to help them get everything they want out of it, in a way.

KP: Yeah. So with so much DIY stuff available, like Bandcamp and social media, tools for recording at home, putting together releases like mastering at home, everything being so much more DIY friendly. Beyond the baked-in advocacy and convenience of coordination and promotion, what benefits might a modern label offer musicians in the DIY landscape?

NC: I think it’s more… I think what I hope I offer is name recognition, right. When someone hears Astral Spirits they have a notion of what it’s gonna be like. “Oh, this sounds kind of cool.” Same thing like when I see something new on International Anthem, I have a sense of what it’s gonna be and I think that’s what a modern label is kind of giving these days. And there’s a lot… I’m trying to think of… even non-jazz, like American Dreams or Trouble In Mind, all those labels have an identity that’s built around a community in a way. Hopefully not to go too far off before I come back, but the Catalytic Sound idea is really is a huge ideal because it literally is a co-op where everyone's making money and it’s a beautiful thing but I think that idea of a label in the good way is that it’s a step towards that, where it’s a community of people that are all trying to help support each other. That’s a big thing to me, is I want to be able to use my label and recognition to build people up and give them a platform. And so more and more that’s what I’m trying to focus on, not as big names. One cool thing that made me think about American Dreams was that he, Joey, has been kind of helping some artists, in particular claire rousay, start their own imprints under his label and release their own records and help them get all their publishing together and all their digital together under their own little space so that they can kind of, you know, build a career and make money off of it. And I think that’s a really cool idea. I like that a lot.

KP: Yeah, that’s awesome. I don’t think I’ve been able to get on the internet without seeing a softer focus somewhere within the past few days...

NC: I listened to it for the first time the other day and it’s as good as everyone says it is.

KP: She got that quietus review and I’m sure I’ll be seeing the pitchfork review soon [laughs] mainstream now. But, I guess, beyond the curational aspect of a label, is there something else it might offer listeners in the modern DIY scene with, you know, kind of a sea of music.

NC: I think the curational, like trying to… yeah, I think that is kind of the primary... I don’t know… My hope would be that through what I’m doing I’m helping create curiosity. I want people to walk away from listening to an Astral Spirits record and be curious about what else this person has done, or like, “Wow, I didn’t think I would like that, but it’s actually not as weird as I thought.” I guess I want it to be more approachable. Because I think there’s the notion, obviously, of improv and jazz being very snobby or high-brow or what have you. My hope is that it would open people up. I would say. Not really…[laughs]

KP: I got it…

NC: Yeah, I think the curation… I’m trying to think what else I want listeners to take away. That it’s not, yeah, it’s not snobby, anyone can get into it. Yeah, we’ll go with that.

KP: That’s perfect. That’s about all that I had planned out, but is there anything else that you would want to shout out or talk about?

NC: I mean I have so many releases coming up... Yeah, I don’t know… I would say, in relation to the last question, one thing I’ve been trying to do is the Astral Editions part, which is the new sister label. And what I’m working on this year is taking that even further out into non-improv stuff, in the same way of like… to where it’s really all connected. I think we’re getting to the point where labels for music… like the word jazz is a really weird word that I’m trying to shy away from right now and not use. But yeah, I think people are more open to more things now. To me, it’s really fun to put… I don’t know if you’ve seen the Powers/Rolin duo, I don’t know if you know Jenn Powers and Matthew Rolin?

KP: no no

NC: I haven’t fully announced it yet but it’s gonna be an Astral Editions LP and they’re incredible. And it’s just hammered dulcimer and 12-string guitar like it’s very… very psychedelic. Like that to me, in these times, sits nicely next to Luke Stewart’s LP or something, like those kind of belong together. And that’s what’s really fun I think… trying to surprise the listener, or someone that would like Astral Spirits... is to put those weird things like Crazy Doberman or just strange things that normally wouldn’t fit.

KP: Yeah, so Astral Editions was originally a digital-only imprint of relatively the same stuff but what are the new directions that you’re taking it?

NC: So, it was digital-only and that kind of, I don’t know, didn’t do… that was fine… didn’t quite do what I was hoping it would. And so my initial goal was to be like.... I was just getting so many demos and submissions I was like, “I wanna put out more stuff. I’ll just do this little sub-label, and eventually they’ll have a record on Astral Spirits.” And that worked for a second, and then I just threw it aside because it just didn’t seem right. It just seemed like it was better to go in a different direction. Like new weird america or whatever. With the stuff I already released like the Hali Palombo, Landon Caldwell/Nick Yeck-Stauffer, Montgomery/Turner, those are more electronic-y, not electronic, but I guess ambient and improv based. And then the Powers/Rolin duo is the next one, that’s gonna be the first LP. And I just announced the Amirtha Kidambi and Matteo Liberatore and that one’s, you know, more jazzy. And then from there I’m doing a record for Equipment Pointed Ankh, which is a group from Louisville, Kentucky, and it’s the guys that run the Cropped Out Festival, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of that?

KP: No...

NC: Ah, It’s the best. It’s one of my favorite festivals ever. He hasn’t done it in awhile, Ryan Davis is the guy. But I’ve played at it a few times, and attended a few times, and it’s just the best. They would have like Peter Brötzmann solo, and then the next stage would be Obnox, and… it was just this insane mix, like Anthony Braxton played it one year. And it’s at a VFW hall that’s on the river and people are camping and it’s just great. Shit & Shine played it one year. It’s just beautiful. So, Ryan and a few others have this group called Equipment Pointed Ankh and it’s incredible. It’s an incredible record, I think it’s gonna surprise a lot of people. It’s just weird. I don’t even know how to describe it. It’s weird. And from there I don’t know. It sort of ties into the musician side of me, since I’m not really playing music these days as much, beyond USA/Mexico, like I always... I’m just touring and like weird rock music which is mostly what I did. So I was like, “Hey, this is my way I can start doing that.” I’m gonna do a record… do you remember Little Wings?

KP: I actually might recognize the name but I can’t put a sound to it...

NC: He’s kind of a folky, weird folky guy, he was on K Records back in the day. He’s still around. Yeah, I’m gonna do a record for him. I kinda reached out to him ‘cause I just thought that would be something I would want to do. So we’ll see. We’ll see what happens. I don’t wanna say I’m turning it into a pop label but it’s like my version of like a skewed pop label.

KP: I think that’s actually super cool. I think Astral Spirits has the reputation of having such a broad catalog anyways and to have this imprint that goes even further into your personal curation is really badass.

NC: Thanks. I hope so.

KP: I guess the last thing I’ll ask is what are you listening to lately?

NC: a softer focus by claire rousay [laughs] It is, actually. I had that on. What else have I been listening to? I think now that I’m post-SX work I’m mostly just trying to catch up on demo recordings or submissions and that kind of stuff. I gotta look at my record player… oh, the, do you know the band France at all? They just put out a new one but they have a sidegroup that I’m in love with and the new record is incredible. It’s German, Tanz Mein Herz. I’ve been listening to that like once a day for weeks now. But them and France are the two bands that… when I’m in a mode where I’m working and I just want something that just kind of goes for awhile, it’s great. I highly recommend it. Endless Boogie. Been listening to them a good deal lately. And then… I got a copy of Lee Morgan eh… Larry Young… I was listening to Lee Morgan before I got on this call actually. Of Love and Peace. I had never had a copy of that record before... Yeah, let’s stick with that.

annotations

annotations is a recurring feature sampling graphic or other non-traditional notation with context and a preference for recent work with recorded examples, in the spirit of John Cage & Alison Knowles’ Notations and Theresa Sauer’s Notations 21. As a non-musician illiterate in traditional notation, I believe alternative notation can offer intuitive pathways to enriching interpretations of the sound it symbolizes and, even better, sound in general. For many listeners, music is more often approached through performances and recordings, rather than through compositional practices; these scores might offer additional information, hence the name, annotations.

Other vital resources exploring alternative notation include Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen’s IM-OS journal and Christopher Williams’ Tactile Paths, each of which reference and link many other resources for this kind of notation.

All scores copied in this newsletter are done so with permission of the composer for the purpose of this newsletter only, and are not to be further copied without their permission. If you are a composer utilizing non-traditional notation and are interested in featuring your work in this newsletter, please reach out to harmonicseries21@gmail.com for purchasing and permissions; if you know a composer that might be interested, please share this call.

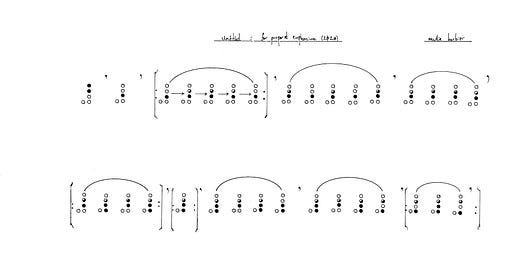

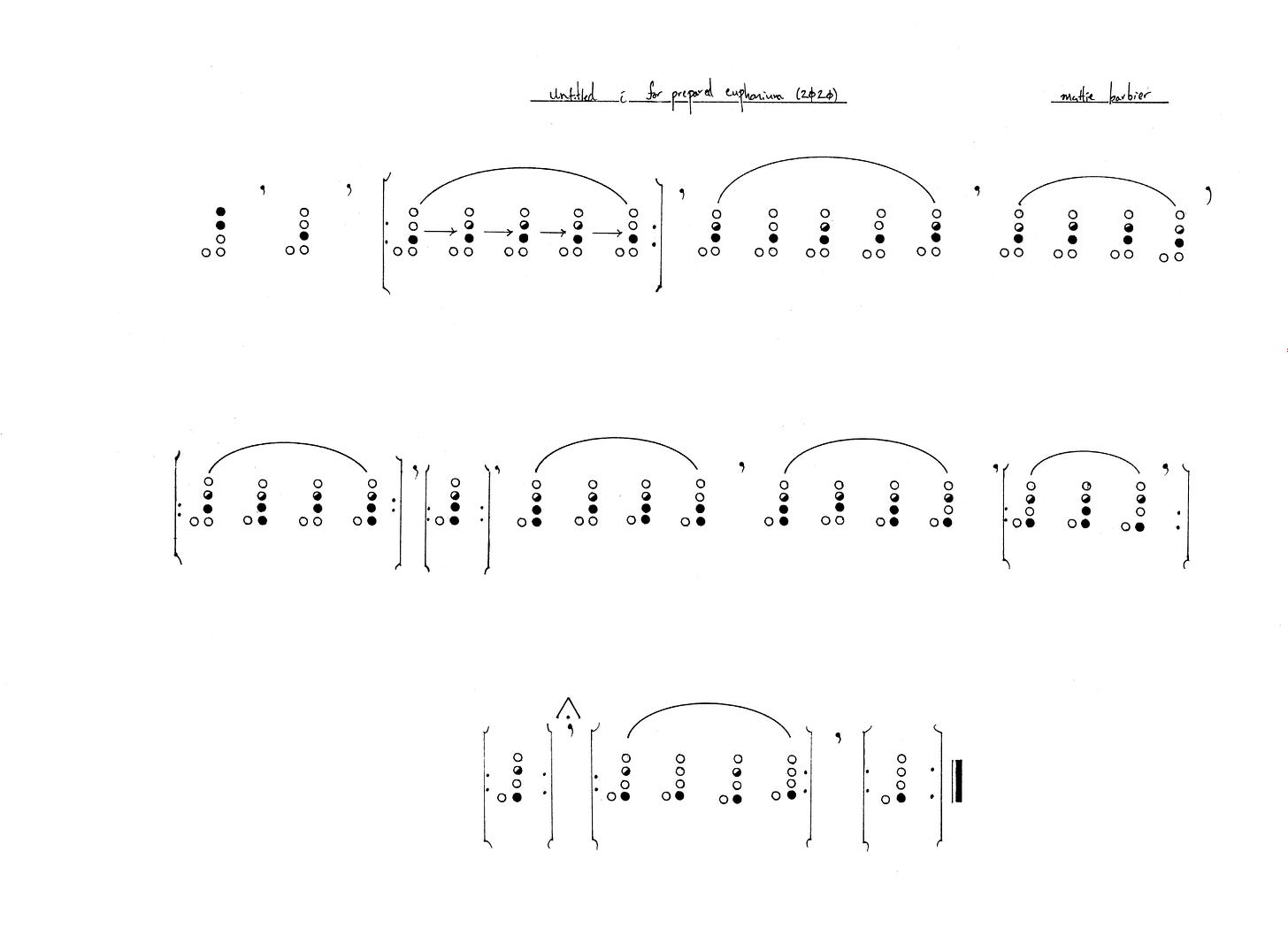

mattie barbier - untitled i (2020)

mattie barbier tends to explore intonation and tuning, noise, and the physical processes of performance, often using low brass instruments. untitled i is a 2020 composition for solo prepared euphonium. It largely utilizes traditional notation: apostrophes for breaths; colons for repeated segments; semi-ovoids for slurs; a caret for increased volume or force; a dot for staccato; a bold double bar to signal the end of the piece. But, rather than a staff with pitches and time, it contains tablature for fingerings on the euphonium. The recording included is performed by barbier.

What I found immediately striking is the breaths, which, along with single-fingering soundings, serve as intuitive markers to follow along with the performance but, indicated especially by the marcato and staccato on the second-to-last breath and the singular inclusion of the third-to-last breath in the repeated segment, also serve as musical material rather than just a performative break - an interpretation bolstered by the prevalence of breath in the recorded performance. The fingerings provide a sense of performance movement, associate sound behaviors with intuitive shapes, and reveal the unstable, subtle action behind what can appear as wildly distinct sounds - the first and third slurred segments wholly tied to small changes in partial action on one valve. But even with the intuitive markers, I still found it challenging to track the performance while following along with the score. While arrows indicate a sequence in the first slurred segment, and this could be assumed for all slurred segments, I suspect there are some repetitions that might start their alternating patterns on the second fingering. But the challenge more likely comes from the capability of minute variations in breath and partial fingerings to significantly change the character of the sound. In using tablature, barbier seems to foreground interpretation and performance problems around intonation and the physical processes of performance that wholly traditional notation might not.

Look for this piece - with a recording of a performance swathed in the otherworldly reverberations of a seven-story steel water tank - on a future barbier release. For now, additional listening might include the 2021 recordings Wolfgang von Schweinitz: Juz (a Yodel Cry) for solo trombone and three spaces for euphonium, trombone, reed organ, and garden.

reviews

Lisa Cameron & Sandy Ewen - See Creatures Too (Astral Spirits, 2021)

Lisa Cameron - with berimbauophone, percussion, and devices - and Sandy Ewen - with guitar and devices - craft improvised metamorphic vibrational environments across 100+ minutes of studio and live recordings on See Creatures Too.

Immediately apparent is the acousmatic quality of the sound. In this relatively wide swath of time, the ear might hear small bells or the collateral hiss and rattle of snare drum wires like bottlecaps nailed to an mbira, the kudzu thrums of nickel and steel strings empowered to vibrate and resonate untended or the familiar intonation of amplification, briefly. Rarely something so easily identifiable as a guitar or berimbauophone. The latter an instrument of Cameron’s invention, using the berimbau as inspiration. But rather than a gourd, its resonator is a box of good sturdy wood found on the side of the road. Similarly, Ewen often uses “trash,” or rather things seldom considered for sound. The result reveals the transformative possibilities of materials beyond their institutionalized identities in which they are allowed to be vibrating bodies true to themselves. Seemingly amplified to communicate amongst themselves as much as they are tools through which Cameron and Ewen communicate. Likewise, feedback and amplification, too often used for aggression and dominance, assume characters of creation, exploration, and sportiveness - especially indicated in the playful titling that might relate to some of the sounds within, the electric roar of “Bananasaurus Rex,” the soaring modulation of “Rhinodactyl,” the beeping birdsong of “Red Spotted Chimerabee.” This community of performers and materials and spaces coalesces to cultivate a kind of ritual energy of reception, intuition, feeling, sensing, and authenticity that is never coerced to climax but a smoothed and sustained jollity. The live tracks, recorded in two different spaces, invite the listener to interpret how these pulsing soundscapes behave, adapt, resonate, and grow in new rooms.

Chora(s)san Time-Court Mirage - Blues Alif Lam Mim (Blank Forms, 2021)

Catherine Christer Hennix gathers a quintet of brass, a trio of voices, and a duo of computer and live electronics in a passage intended to unveil the origins of the blues in the traditions of raga and makam on the 80-minute Blues Alif Lam Mim. This release is a reissue of a 2014 recording originally released in 2016 and originally titled Live At Issue Project Room.

A drone like tanpura and the reverberating devotionals and praises of Ahmet Muhsin Tüzer begin the set. Several minutes of these alone invite the listener to step inside the drone. Its many harmonic layers imparting a deep spatiality that telescopes the perception of the ear to expand the mindfulness of its diverse pulses to form a terraced listening experience that might feel like warping time and space as the ear moves backward and forward, up and down, sidelong and laterally through its morphologies. The drone continues for the duration of the performance. And seems fundamental, not just in its endless presence but as the origin and doom of nearly every other sound as they almost imperceptibly materialize from its ooze and likewise fade back into it. The brass a turbulent eddy shed from its laminae, the gradient between them sublimating novel harmonic interactions in its ether. The electronics subtly accentuating its corporeal low end or some other singular aspect at a time. The voices - all mellifluous praises - provide a kind of contrapuntal melodic movement marker to orient the ear in the drone. And while the brass is more often sustained, near parallel to the swells and swales of the drone, there is some familiar movement which might signal the revelation of the blues, my ears having grown up with that tonality. It ends but there’s a sense it could continue forever

The performers on this recording include: Amir ElSaffar (trumpet); Robin Hayward (tuba); Catherine Christer Hennix (voice); Hilary Jeffery (trombone); Elena Kakaliagou (horn); Amirtha Kidambi (voice); Marcus Pal (electronics); Paul Schwingenschlögl (trumpet); Stefan Tiedje (electronics); and Ahmet Muhsin Tüzer (voice).

Bryan Eubanks & Xavier Lopez - Natural Realms (Sacred Realism, 2021)

Bryan Eubanks and Xavier Lopez engineer shifting harmonic and rhythmic structures for electronics, soprano saxophone, and percussion on the improvised and live recording of a 50’ performance on Natural Realms.

The recurring timbres of the electronic systems seem to occupy most of the space - clicks, low end bumps, beeps and bloops, feedback swells. Often appearing in linear beats, with exceptions of sometimes hastening and slowing tempos, the off-kilter click of “Realm 4,” and tonal steps, the timbre of which blurs between something like steel drum and keyboard. Not presented for sustained durations but as discrete rhythmic units of varying lengths, modules ever repatterning, organic and alive, an iterating defragmentation. Its structures perhaps too dense to deconstruct from listening memory, its pacing not chaotic but maybe just quick enough to discourage tracking its forms without some contextual help. These sounds linger a little, reverberate, and resonate a little to produce light harmonic interactions, though the throbbing pulsings in feedback are usually readily apparent. The human percussion I hear is all woodblock, providing another contrapuntal line in the system’s polyrhythms, and I think it’s odd to be able to possibly distinguish some human element in this woodblock playing when there is another generated sound like woodblock, sometimes concurrently. I might have missed the soprano saxophone if not mentioned in the notes, and I think it accompanies some feedback swells, a parallel inducing richer harmonic interactions in the grid between them. While this was developed and recorded before their work with Catherine Lamb’s wave/forming (astrum), it feels related, a complex harmonic latticework though less long introduction and more house of cards, fallen and built again with variation ad infinitum.

Sarah Hennies - Psalms (self-released, 2021)

Sarah Hennies performs four early original foundational compositions and one Alvin Lucier composition for solo percussion exploring a sound that continues to inform the work she composes today on the 45’ Psalms. This release is a reissue of a recording originally released in 2010.

“Psalm 1,” for vibraphone, begins with relatively rapid repetitive strikes on a single bar, immediately inducing howling harmonic interactions among soundings. Sometimes so powerful that they might draw the ear from even hearing the original hits, developing characters nearly wholly distinct from the strikes save for temporally displaced artifacts of the momentarily damped vibrations from mallet on bar. With a deep spatiality, not just one dancing pulse but a hall of them, their various patterns amplifying subtle variations in strike tempo, force, and placement. A second mallet, on what sounds like another bar, just offset from the beat of the first, enters, inducing new harmonic behaviors. The first exits. After some time, a third enters. “Psalm 2,” for snare drum, uses similar strategies for similar effects, its overtones talking almost like the drum does, from the wobbly center towards the taut perimeter and the jangle of the frame. “Psalm 3,” for woodblock, too, its harmonic characters changing from chittering screeches to alien hums and a menagerie of others, presumably as the mallet strikes in different proximities to the damping hand. The Psalms each illuminate the complexity of even simple soundings, simultaneously repetitive and not - their marked transformations rising from minute variations, emanating uncanny psychoacoustic effects from familiar materials, with an intimacy that ensconces the ear in its waves - it would be wonderful to walk around the room to hear these interactions in space, but this recording still conveys the kind of harmonic magic these pieces make possible. “Silver Streetcar for the Orchestra,” composed by Alvin Lucier in 1988, seems a nod towards inspiration and another similar iteration for triangle but accentuates tempo changes, the harmonics particularly demonstrating how they carry on with a life of their own as they continue dancing with abandon even after the duration between strikes increases considerably. Similarly, the brief early work for vibraphone, “untitled (1918-2000),” composed eight years before the Psalms, features a marked silence - with one faint note - separating sections of similar harmonic strategies. There’s a feeling that, while there is no sounding to hear, the brain continues to perceive the ghost of the wailing beating well into that silence.

Sarah Hennies also released the community sound collage, Memory Box, and the orchestral work, Falling Together, this past month.

Magda Mayas’ Filamental - Confluence (Relative Pitch, 2021)

Magda Mayas amasses a string-based octet on Confluence for a 50’ performance of an original composition based on the confluence of the Rhône and Arve rivers.

It seems difficult for me to engage the sound without the context of confluences, but maybe that’s appropriate here. Its broad form flows for the duration, with a relatively tight range of tempos and dynamics that can appear anonymous at scale while still conveying the mercurialness and teeming textures of rivers. Closer observations of a sound reveal processes like closer observations of a stream might reveal. Breathy reeds’ wet embouchures like fetch lapping the surface, their bubbling tones the aqueous pops of cavitation or - I think these are alluvial streams - the skip of sand and silt suspended in fluid across the bed. Glissando surges like a wake on the bank. The overlapping shear of strings of different timbres the mingling tongues of waters of different chemistries thrust into the same space. Plucked rhythms and other discrete soundings the wild vectors of turbulent flow. The almost imperceptible pause of decision the almost imperceptible convexity of the water surface at a confluence. There are even moments recalling bird calls and insect chittering, as if to include the ecosystem at the merger. Its textural density invites ever deeper listening in the way the complexity of streams will always invite study. The ensemble is all powerhouse performers but, like a stream is one stream with one name below the confluence, though they may lend their distinctive voices, this is a singularly cohesive unit that subsumes individual style.

The performers on this recording include: Christine Abdelnour (saxophone); Anthea Caddy (cello); Angharad Davies (violin); Rhodri Davies (harp); Magda Mayas (piano); Zeena Parkins (harp); Aimée Theriot (cello); Michael Thieke (clarinet).

Microtub - Sonic Drift (Sofa, 2021)

Microtonal tubists Robin Hayward, Peder Simonsen, and Martin Taxt continue to document the unique harmonic spaces and interactions of their instruments and ensemble across two tracks on the nearly half-hour Sonic Drift.

The 14’ title track is an unaltered performance of the Hayward composition that provided the material for the remix, “Chronic Shift,” from 2019, which looped a harmonically-rich dyad in hastened and slowed time, separated by a slow-motion beating pattern, with glitched production and sonar pings to further diversify movement. All three low end long wave heralds sound at once, each tuba emitting its own deep strata of harmonic layers. When they pause, the ghost pulse of their instruments’ vibrations reverberates. Relatively sustained soundings stagger, rotate, and repattern to weave new combinations of harmony. As time progresses, these threads reduce the number of silences and the reverberation that haunts them but provide more opportunities for harmonic interactions that produce faint beatings. I’m assuming some things about tuning and timbre here, but the high-frequency hums of the two microtonal C tubas, the guttural chug of the microtonal F tuba, their individual stacks of harmonics, and the wave interaction between them form a delightfully dense polyrhythm of pulses. The collectively composed, 13’ “The Pederson Concerto” adds a soft synthesizer that begins with seemingly low amplitude and frequency, mostly apparent during tuba silences, but increases both towards the end of the track and eventually appears higher in the mix than the tubas. After a brief introduction from a solo (I assume) Simonsen, there’s a particularly powerful moment where all three tubas sound at once. From there it is again a complex plaiting to form different combinations of harmony with rich pulsing structures rising from harmonic interactions and more pronounced harmonic beatings than the previous track, sometimes achieving a glassy siren resonance. Just as the synthesizer begins to draw the ear from the tubas, it stops. And the tubas assume a leapfrog pattern, one sounding beginning just as one is ending, resisting the impending silence, until the end.

Yoshi Wada - The Appointed Cloud (Saltern, 2021)

Yoshi Wada’s installation of custom pipe organ, sirens, sheet metal, pipe gong and more, conducted by an interface and software designed and on this recording operated by David Rayna, is joined by timpani and tam-tam and a trio of bagpipes (including Wada) in an hour-long performance on The Appointed Cloud. This release is a reissue of a 1987 recording originally released in 2008, remastered by Stephan Mathieu.

The form seems simultaneously cyclical and progressive, with recurring sections of something like distant bells in an acousmatic gust, rolling timpani thunder and the rippling of sheet metal wobbling, tanpura-like bagpipe drones shifting towards woven ecstatic ululations, and other motifs in some order though perhaps not beholden to an order and an organ that grows from measured sustained tones to giddy staccato flights. Other aspects also appear liminal too. The drums and bagpipes can be martial; the bagpipes, languorous organ, and bells funereal; the bells, sirens, and something like a stick along a fence or ringing clock signals for alarm. But despite these graver associations, the total performance feels more celebration than tension. The construction of it, the DIY build, the computer control, the instruments embedded in the architecture, foregrounds some interface between human and inhuman or industrial. But this complex expansive melange is all underpinned by a seemingly singular focus on space and air and the resultant pulse. The throb of sustained organ and cadence of hammered organ, the beating patterns of droning bagpipes and the polyrhythm of their snaking chorus, the reverberant waves of resonant bells, the plain beat of the drums, the aural pulse of sheet metal visually manifested in the material. It is as if the very room is animated, given breath and pulse and brought to life by the music.

The performers on this recording include: Bob Dombrowski (bagpipes); Wayne Hankin (bagpipes); Michael Pugliese (timpani and tam-tam); David Rayna (installation operation); and Yoshi Wada (bagpipes).

Yoshi Wada passed away this month. To honor his musical legacy, Saltern, the label organized by his son Tashi Wada, has made his work streamable on bandcamp.

Thank you so much for reading harmonic series. If you appreciate the music and the words about it in this newsletter, consider sharing it as a method to advocate for the music and the people that make it possible. harmonic series will always be free and accessible without a sign-up or sign-in but, if you appreciate the efforts of the newsletter specifically, consider donating. As always, readers are encouraged to reach out about anything at all, even just chatting about music, to harmonicseries21@gmail.com.